ANONYMOUS

“I have a boyfriend.”

It’s a phrase all too often used defensively, intended as a shut down to unwanted sexual advances without necessarily rejecting the harasser. A phrase all too often used regardless of the speaker’s actual relationship status, gender orientation, or average level of honesty in other scenarios. A phrase used because sometimes it’s just easier to tell the creepy guy at the bar/train/gym/[insert-public-space-here] that you are already with someone — and that’s on you, not him. It sounds like a little white lie, but it’s a level of deception that runs far deeper than the unpleasant encounter and belies the truth and reality about perceived impoliteness of women today.

What happens when expectations of politeness collide with honest discussions of wants, needs, and respect, in a moment where one’s sense of emotional and physical security is at risk?

A woman’s space, time, body, and decisions should be respected because they are hers — not because they are anyone else’s. Therefore, in theory, a rejection to an unwanted advance should always be sufficient without the “I have a male significant other” qualifier. But in today’s male-centric society, the “male” in “male significant other” is still the most important word and the one you must not offend. Some believe that using the “boyfriend” excuse to avert unwanted attention only reinforces the underlying patriarchal conventions of street harassment. It is as if by saying, “I have a boyfriend,” the woman is also saying that she belongs to the boyfriend and, therefore, the harasser should not violate the property rights of his fellow bro (because the Bro Code, obviously). Not only is this perspective incredibly sexist, it is also perpetuating, at a systemic level, a degree of self-deception; if you say it often enough, you might start believing in the Bro Code too. A popular 2013 column by writer Alecia Lynn Eberhardt argues that, “The idea that a woman should only be left alone if she is “taken” or “spoken for” (terms that make my brain twitch) completely removes the level of respect that should be expected toward that woman.”

“It completely removes the agency of the woman, her ability to speak for herself and make her own decisions regarding when and where the conversation begins or ends. It is basically a real-life example of feminist theory at work — women (along with women’s choices, desires, etc.) being considered supplemental to or secondary to men, be it the man with whom she is interacting or the man to whom she ‘belongs.’”

– Alicia Lynn Eberhardt

10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman | Source: © Rob Bliss Creative/YouTube

In 2014, a street harassment awareness video commissioned by the advocacy group Hollaback went viral, with over 10 million views in its first 24 hours online. The video depicted a woman walking through the streets of New York City, being harassed and receiving catcalls while going about her day. In this video, the woman largely ignored the catcalls, and several of the men expressed their frustration at her silence. One man yelled out, “Someone’s acknowledging you for being beautiful. You should say thank you more!” Another man actually followed her down the street, asking “You don’t wanna talk? Because I’m ugly? Huh? We can’t be friends, nothing? You don’t speak?” Her response is the behavior deemed impolite, not the initial unsolicited catcalling from the numerous men around her. It should also be noted that while the video was trying to raise awareness about street harassment, it has also been criticized for over-representing men of color as the major perpetrators of street harassment, as well as for not asking for consent of appearance from the woman featured, who has actually received online rape threats because of her appearance in the video. So while the way in which the video was created has lots of problems (some of which directly related to ideas of deception; for example, the woman in question was an actress), the content begs the question — if being truthful generates this much animosity, does it give more credence to the use of the “boyfriend” deceit?

In an article published earlier this year, writer Hanna Brooks Olsen explained that she responded politely to catcallers because she felt it was a self-defense mechanism, albeit one she realized could reinforce the very behavior she was encountering. “But my body is not the battleground for this fight and my personal safety is not a currency I am willing to exchange for ending it because even if I cash it in it will persist,” she writes.

“I would rather get home safe at night than take up the charge of ending male entitlement when it stumbles my way because the truth is, my compliance doesn’t cause male entitlement and my lack of compliance isn’t enough to make it stop.”

– Hanna Brooks Olsen

She makes the claim that her single act of “non-compliance” would do little prevent the overall incidence of sexual harassment, and instead could make her vulnerable. Her article describes the way that fear and anxiety play significant roles in women’s obligation to politeness in the face of harassment.

Laura Logan at Kansas State University notes that this kind of fear impacts women’s behavior, decisions, and sense of independence, including the development of personal risk management strategies such as walking with a friend to changing one’s appearance. She discusses the ways in which women’s fear of violence (particularly sexual violence) impacts their lives and their decisions. According to her, “women fear violence more than men, at least when measured by crime statistics […] the most promising explanation for the fear-crime disparity is that women witness and endure a wide range of men’s dominance and violence against women and girls — much of it not identified as either violent or criminal by the victim, and little of it reported to the authorities.” She cites research that states this fear to be stemming from personal experiences of violence and harassment as well as identifying as part of a victimized group (in this case, women) who are perceived as being regular targets of violence.

Given the numerous data and information we have about the fear and anxiety caused by harassment, why are the victims (often women) still held to standards of polite behavior when addressing their harassers (often men)? For many women, gendered expectations of “politeness” already impact most facets of daily life, from the commute to an entire career path. What happens when expectations of politeness collide with honest discussions of wants, needs, and respect, in a moment where one’s sense of emotional and physical security is at risk? Ignoring a catcaller doesn’t feel good. But does it feel good to talk about having a “boyfriend” when you don’t have one, you may not be interested in one, and you definitely don’t need one to be validated as an individual? Can a victim of harassment respond in a way that is honest and assertive in an environment where fear of repercussions lingers in every encounter?

A woman’s space, time, body, and decisions should be respected because they are hers — not because they are anyone else’s.

Truth be told, if one of the most significant consequences of sexual harassment is the fear and anxiety it invokes in women — whose decisions are then informed by this emotional weight — then any tactic that reduces this sense of terror and concern is a worthwhile consideration.

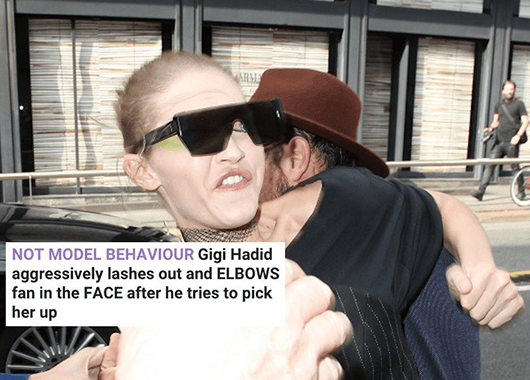

Gigi Hadid Assaulted by Vitalii Sediuk | Source: Junkee

Recently two very public instances of harassment have captured global social media attention. During Milan Fashion Week, supermodel Gigi Hadid was physically assaulted by a man who lifted her up and did not let go until Hadid herself elbowed him in the face. All of this occurred with Hadid’s bodyguards present and in front of numerous people, male and female alike. Why no one acted preemptively — or even actively as they witnessed Hadid’s feet leave the ground — in support of her is a mind-boggling question. In an interview with Lena Dunham — herself no stranger to online harassment — Hadid said that, “I felt I was in danger, and I had every right to react the way I did.”

“The first article that was posted about the incident was headlined: “Not model behavior. Gigi aggressively lashes out and elbows fan in the face after he tries to pick her up. The supermodel angrily hit an unknown man before running to her car.”

That’s when I really got pissed. First of all, it was a woman who wrote the story with that headline. What would you tell your daughter to do? If my behavior isn’t model behavior, then what is? What would you have told your daughter to do in that situation?”

– Gigi Hadid

Kim Kardashian Assaulted by Vitalii Sediuk | Source: © Xposure/Metro

Just a week later, the same harasser that assaulted Hadid was at it again, this time approaching reality TV celebrity Kim Kardashian on the streets of Paris, kneeling down and literally kissing her buttocks. In this instance, Kardashian’s bodyguards were a bit more pro-active than Hadid’s and managed to wrestle the harasser to the ground, but not before he has violated the rights of Kardashian to her own self, space, and body. This self-styled “prankster” is Vitalii Sediuk, a so-called “reporter” who has been known to attack various celebrities as a means of “protesting” fame and celebrity culture. While men are not immune to his attacks (just ask Will Smith), it is his women victims who suffer the most from this crude and perverse method of sensationalism. As entertainment reporter Amy Zimmerman eloquently puts it, “Sediuk isn’t an activist, an artist, or a revolutionary. He’s just another dude with an unsolicited opinion, touching a woman’s ass on the sidewalk.”

When this is the world women live in — when even the most famous individuals, who have an entire of army of people to protect them from these situations, still fall victim to sexual harassment — then perhaps a little white lie is the least of their concern. By all means, respond to the given circumstances of a sexual harassment encounter in your own terms and how you feel most safe and secure during the episode. Whether it’s some form of deception or an honest right hook, what matters most is the agency and respect that the victim must have for themselves — elements of one’s sense of self that cannot be sacrificed for the sake of politeness.

I recently tried out a more assertive approach to addressing street harassment. A few weeks ago, a guy adjusting his bicycle chain stopped what he was doing to yell out to me on the street.

“You should smile, honey!”

(Apparently, my facial expression while contemplating my grocery list on the way to Giant did not exude degrees of joy and happiness adequate for a woman in a public setting). I replied back:

“You know what you said is considered extremely rude and condescending toward women?”

Unfortunately, the harasser had headphones on, assumed I thanked him for reminding me to wear my happy face, and smiled before hopping back on his bike and cycling away.

But did I feel more agency in the face on an undesirable situation?

You know what? I did.