MICHAEL DONNAY

In December 2015, an episode of Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee aired with Jerry Seinfeld and President Barack Obama. When asked about how difficult it was to get a sitting president to come on his show, Seinfeld replied that the White House staff was eager to agree. That in fact, they’d been considering reaching out to Seinfeld themselves. And so the nation was graced with images of the sitting President of the United States cruising the White House grounds with a famous actor in a 1963 Corvette. They discussed presidential commemorations and Obama’s workout routine. They joked about nachos and how they each dealt with fame. As simple as their twenty-minute exchange might seem today, the whole scenario would have been unthinkable for much of American history. Indeed, Booth’s assassination of Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre was for a long time the closest connection between the acting profession and national politics. In this way, as in so many ways, the Obama presidency stands out as a clear example of a major shift in American culture. The shift, in this case, is of the actor from the margins of society to the main stage of celebrity culture.

Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee: “Just Tell Him You’re The President” (Season 7, Episode 1) | Source: © blacktreetv/YouTube

That shift, however, did not happen overnight. In the European dramatic tradition, as far back as classical antiquity, actors were considered little better than prostitutes willing to sell their bodies for money. The Latin term infamosi, from which we get our concept of infamy, was regularly applied to the acting profession. And while this attitude is by no means constant across the subsequent millennia — the Jesuit use of theatre as a tool for teaching virtue in the early modern period is a good example — theatre and its practitioners remained broadly suspect until well into the modern period. Even as the performing arts gained social status in the 17th- and 18th-century, performers generally remained near the bottom of the social hierarchy. Now, however, our biggest actors are the biggest celebrity figures in contemporary culture, and we’re left with two questions: when did acting become a socially rewarded career and when did it become a financially rewarded one? The answer to the first one is complicated, and like any good modern historical question, has to do with the long 19th-century, cultural dislocation, and technological developments. The answer to the second one, frankly, is that it still hasn’t.

Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your English Playwrights

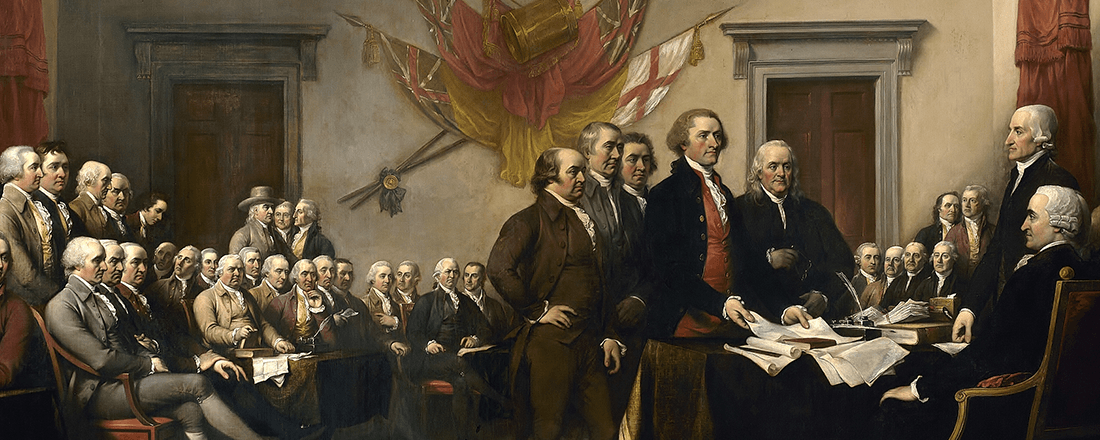

Following the American Revolution, fame in the United States was the purview of political and military heroes. George Washington is perhaps the best example, but any of the men associated with the founding or framing of the young nation would fit the mold, too. These men (and they were almost exclusively white and male) embodied or were made to embody the best qualities of the country: morally upright, concerned with the common welfare, wealthy but not extravagant, forceful in rhetoric but gentlemanly in manners. They may have enjoyed some of the aspects of what would now be called celebrity, but their notoriety was grounded in tangible political or military achievements. They also provided a more foundational social function, standing as symbols of the United States’ worthiness to be a member of the international community.

JOHN TRUMBULL’S 1819 PAINTING DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE, WHICH FEATURES SOME OF THE FOUNDING FATHERS | Source: Wikimedia Commons

With the death of this generation in the early part of the 19th-century, American cultural creators worked to manufacture new models to take their place. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett are both good examples of this trope — self-reliant, virtuous, industrious, and freed from the constraints of a European past. Through Lincoln and the 1860’s, this type of figure served as the model both for American virtue and as the best way to achieve lasting fame in the public imagination.

The shift, in this case, is of the actor from the margins of society to the main stage of celebrity culture.

Unsurprisingly, actors did not fit neatly into this model of “public hero as virtue model.” For one thing, despite the efforts of some of the craft’s best practitioners, actors still struggled with the rakish reputation they brought over from Europe. The more egalitarian social order of the United States allowed for some improvement in their stature, but that movement never brought them above the stature of artisans. There were strong Spanish and French theatrical traditions already present in the future United States, but it was the English tradition that would come to dominate mainstream white theatre in the new republic. Although the American war of independence produced a great, self-conscious throwing off of British culture, theatre remained relatively immune from this movement. English actors and English plays would hold an almost absolute monopoly on the American theatre for the first half-century of its existence.

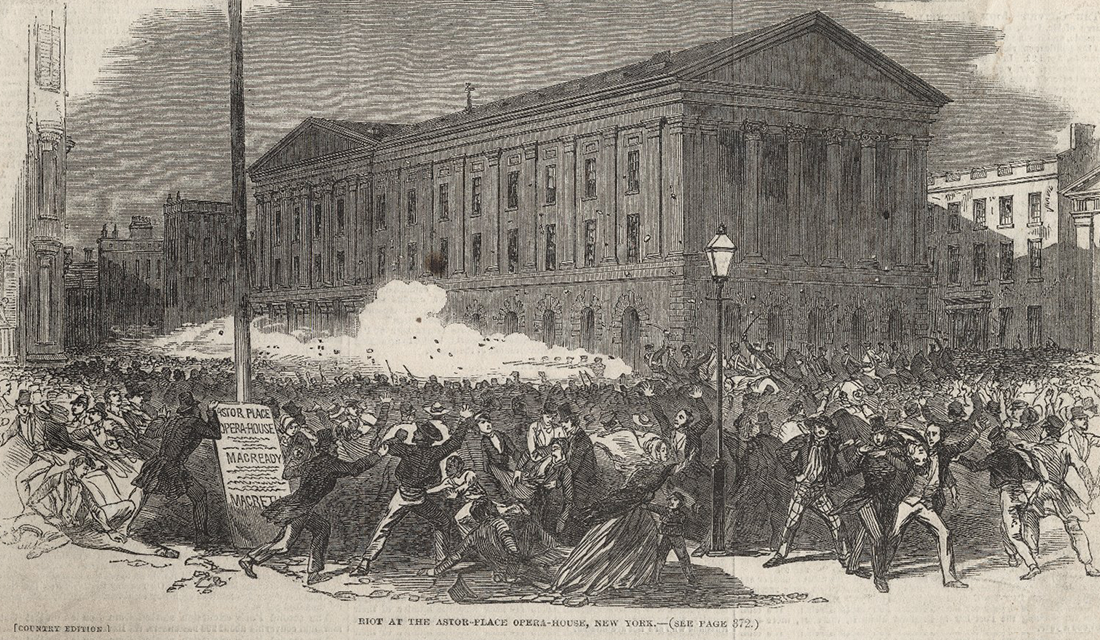

This dominance set the terms for celebrity for actors — in short, to be famous you needed to be British. Even with the advent of leading American-born performers in the 1830’s and 1840’s, English stars like Edmund Kean, Fanny Kemble, and Junius Brutus Booth could and would compete successfully with American actors like Edwin Forrest as the top stars of their day. And since American theaters produced a similar repertory of shows, largely centered around Shakespeare and other English classics, it was easy for an English star to slot into roles with a company for a number of performances. These stars also drew audiences, who were interested in seeing the differing interpretations these enticingly foreign actors brought to familiar roles and plays.

Astor Place Opera-House Riot of 1849 | Source: Folger Shakespeare Library(CC-BY-SA-4.0)

The relatively small and homogenous repertory of these theaters, while advantageous for the stars, also meant that the threat of easy replacement always hung over the heads of the less famous actors sharing the stage with them. Most working actors of the time specialized in a line of business — a particular type of stock character, like leading lady, villain, or low comedy. Actors who mastered a line of business could make a relatively lucrative career if their luck held. But stability was uncertain, and employment could be terminated at any moment.

In the European dramatic tradition, as far back as classical antiquity, actors were considered little better than prostitutes willing to sell their bodies for money.

So, while stars would come to dominate the theatrical landscape for most of the 19th-century, these stars were not (yet) celebrities in the modern sense. Most foreign actors were confined to certain theaters in specific cities — the Park Theatre in New York City is the best example of a patrician establishment serving an upper and middle class clientele — while American-born actors were often shunned from such venues and had to find homes at theaters like the Bowery Theatre, also in New York City, that catered to a working-class audience. And while a star might command a greater salary than her fellow cast members and be relied upon to attract a greater audience, this was mainly a difference of degrees.

Adelaide Ristori | Source: Wikipedia

Very few, such as Adelaide Ristori, an Italian actress who first toured the U.S. in 1866 and performed primarily in Italian and French, drew large crowds because of celebrity alone, and ironically, her arrival marked the near-end of the dominance of the American acting profession by European stars.

19th-Century Triple Threat

As that door closed, however, a number of major changes were underway that would open another door — this one to a new type of mass celebrity that (a select number of) a new generation of actors would soon claim. Following the end of the Civil War through the 1920’s, American popular culture underwent a seismic shift that opened up new possibilities for celebrity for a wider range of people, especially actors. This shift was made possible by a number of cultural and technological developments that altered much of American society: the communications revolution, increased immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, increased urbanization, and the emergence of film and radio as truly national media. Together, they created the environment in which our contemporary understanding of the actor as celebrity was born.

Particularly with the increased availability of photography, it became easier to create an image, both figuratively and literally, of the actor in the public’s consciousness.

The communications revolution that began in the 1870’s and reached its peak in the early 1900’s reshaped how Americans received their news and for the first time created a mass media wherein the reader was also a consumer. The main vehicle for this revolution was the urban newspaper and the magazine, both of which exploded in popularity. The development of photography and the means to reproduce images on a mass scale meant that publications could now include graphics as part of their regular output. Other technological advancements in printing technology, like high-speed presses and linotype machines, as well as institutional developments like syndication and news gathering organizations like the Associated Press allowed for output to greatly expand. Increased literacy and access to leisure time ensured a growing reading public.

The storied history of newspapers | Source: © CNN Business/YouTube

At the same time the media was looking for more content to fill its pages, the public’s interest was shifting from a concern over character towards a concern for personality. And who has more personality than performers? Particularly with the increased availability of photography, it became easier to create an image, both figuratively and literally, of the actor in the public’s consciousness. Thus, a virtuous circle developed wherein readers wanted to know more about entertainers, particularly actors, and the mass media was happy to supply it. It is during this time that journalists pioneered the interview as a form and famous acting families like the Barrymores were regularly featured in national outlets. Similar to the demands of the 24-hour news cycle today, the proliferation of news outlets and competition between them drove journalists to pursue human interest stories at an increasingly rapid pace.

Immigration, too, particularly from Eastern and Southern Europe, was changing the face of American cities and helping to shift mainstream American culture away from the elite, Protestant, and Anglo-centric tastes that had dominated throughout the 19th-century. What emerged in its place was an urban culture drawing on idioms that deliberately appealed to a broader swatch of the public. Grounded in the cities — where social life was increasingly fragmented by neighborhood, ethnic group, and class — entertainment provided one of the few touchstones that could appeal to a wide-enough demographic to be commercially viable at scale. This effect was evident to cultural commentators at the time, one of whom noted in 1880 that, “[Drama] now makes such a large part of the life of society that it has become a topic of conversation among all classes, furnishing an endless gossip to the trivial, and intellectual interest to the serious.”

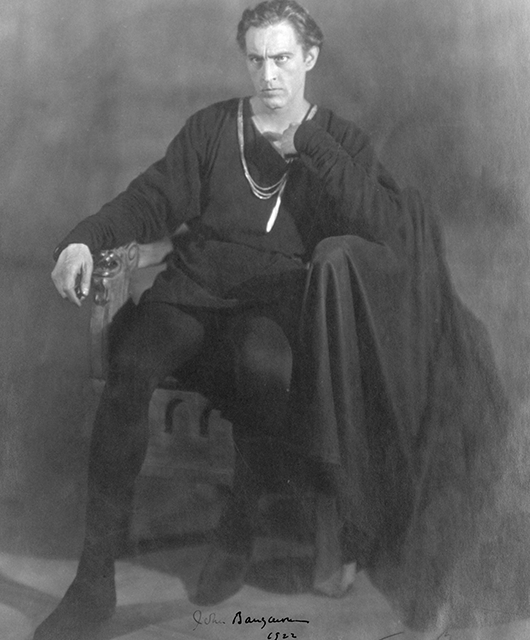

John Barrymore as Hamlet | Source: Wikipedia

This symbiotic growth of public demand and a burgeoning supply of entertainment gave birth to the star culture we know today. Although stage actors like John Barrymore were early and regular features in the press, it was film and radio actors who would end up dominating the public’s attention by the 1920’s and 1930’s. Radio and film were more conducive to the engines of celebrity both because they were produced on something akin to an industrial scale — the apparatus of the Hollywood studio system, for example, was massive — and because they created figures with a truly national reach. Hollywood in particular was adept at packaging movie stars like Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn into cultural products for public consumption. The few actors who were able to reach that level of prominence were made into celebrities with incredible staying power — John Wayne was rated the most popular man in America 14 years after his death. Like the heroes of the early republic, these stars were supposed to embody the best of American values.

So if movie stars had made the switch from low-status to high-status career by the 1940’s, what about the rest of the actors? Surely, some of the prestige of the stars rubbed off on the rest of the profession (anyone who has heard an actor tell a story about the one time they worked with Lady Gaga can relate). But while the rising status of the star was marked by technological shifts and the rise of mass media, the respectability of the working actor owes much more to the organized labor movement.

“He best serves himself who serves others”

The same forces that gave birth to the industrial entertainment industry and allowed Hollywood stars to be packaged so effectively also drove down (the already poor) wages and working conditions for the rest of the acting profession. At the turn of the 20th-century, it was common for actors to be forced to rehearse without pay for 10-12 weeks before a show opened. They’d often be made to perform a dozen shows a week or more. And when productions went bankrupt, actors were often abandoned without pay. (That’s how Hattie McDaniel, future Academy Award winner, ended up working in a club in Milwaukee when the production of Showboat she was working on went under.)

Hattie McDaniel – The First African-American To Win An Oscar (Mini Bio | BIO) | Source: © Biography/YouTube

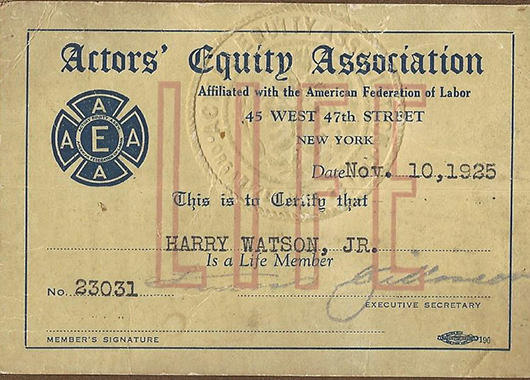

In response to these conditions, actors began organizing. Vaudeville actors formed the White Rats of America in 1900 to negotiate for better pay from the managers of the circuit houses they performed at, but the association disbanded shortly after a failed strike in 1916. New York theatre actors formed the Actors Equity Association (AEA) in 1913 in response to the power of the United Manager’s Protective Association, a powerful collection of theatre managers, producers, and bookers. In 1919, Equity voted to strike for better working conditions and after 35 days — in which 18 shows closed and $2 million dollars were lost by theatre producers — they secured a new contract. For the first time, professional actors were guaranteed a standard work week and uniform work conditions across the industry. Actors in the film industry unionized later, forming the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) in 1933 in response to massive pay cuts instituted by the major movie studios.

Actors’ Equity Association strike of 1919 | Source: © American Theatre Magazine

1925 Actors’ Equity Association member card | Source: Stage Directions

For the majority of actors who did not achieve star status, union membership offered access to some elements of the status afforded to stars by virtue of their celebrity. Both SAG and AEA provided a semblance of financial security for their members, while at the same time offering a level of middle-class respectability to the profession that comes with unionized labor. An actor who secures regular work under a union contract can be assured of health and retirement benefits, a reasonable salary, and safe working conditions. Regardless of the success of the labor movement for actors, however, the majority of working actors are still not able to make their entire living from acting. While a star in a feature film can earn upwards of $20 million for a few weeks of work, more than 90% of Equity’s members made less than $50,000 under union contracts in 2016-17.

Unpaid, But Good Exposure

In their book Freakonomics, economists Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner ask a provocative question: Why do so many drug dealers still live with their parents? It turns out it’s because drug dealing isn’t as lucrative as the movies would have you believe. While the leaders of the drug trade make a very good living, the average street-level dealer takes home about $3.30 an hour. And while Idris Elba, who played a major criminal figure in The Wire, is worth several million, an actor working an Equity contract in Chicago can still be making just over $6.15 an hour. So we shouldn’t be surprised that many actors also live with their parents.

Actors face a steep pyramid, with the vast majority of pay and prestige accumulated by a few at the top while the majority of actors labor in underpaid obscurity. Like street-level dealers, they are willing to accept low wages, long hours, and significant career instability because the rewards of promotion are so high, even if the odds of making it to the top tier are staggeringly low. In this way at least, the rise of the actor as mega-celebrity has been damaging for all those left behind. The myth that through hard work and perseverance you can eventually make it big — Jon Hamm’s career is a good example — serves as an excellent tool for industry leaders to keep wages low, hours long, and working conditions poor. “Unpaid, but good exposure” on casting calls is the most obvious expression of these forces at play.

MOVE: The Working Actor: How Much Can I Really Make? | Source: © SAG-AFTRA/YouTube

Still, acting has undeniably seen major gains in the last two centuries. Socially, actors have moved from the margins of society squarely to the center — even welcomed into the White House. And economically, some have vaulted into the ranks of the super-wealthy or have moved into the middle class. In that way, the profession can be counted among the great successes of the American story. But, as we’ve seen, that success story, like many in the American canon, comes with qualifications.

For perhaps better than any other industry, actors are also a bellwether for the forces of late-stage capitalism. The accumulation of massive prestige and wealth by a few at the top, while keeping the wages of the rest of the industry low — check. The glorification of unreasonable work hours — check. The democratization of culture through the technology — check. The ultimate ascendance of personality over character — check. These forces, which were responsible, in part, for the creation of the actor-as-mega-celebrity might prove to be the undoing of her underpaid colleagues. There is some hope for the future — a new collective-bargaining agreement between SAG and the major online studios like Hulu, Amazon, and Netflix offers better compensation for actors working on original content. But at the same time, self-made content creators on platforms like Instagram are challenging the celebrity actor for cultural supremacy. If there is hope for the future of the profession — for stars and working actors alike — it lies in the ability to stay on the leading edge of the technological curve. Otherwise, for many actors at least, “Netflix and chill” may just become a reference to the heating bill they’re struggling to pay.