NORA ROSENGARTEN

As we consider our issue theme of conversations, each of us at SixByEight Press took a little bit of time out of our days to engage in open dialogue with writers, collaborators, and mentors from our own personal and professional lives. We hope that in having these open-ended chats, we can reflect upon and gather a few key lessons from this most human of rituals.

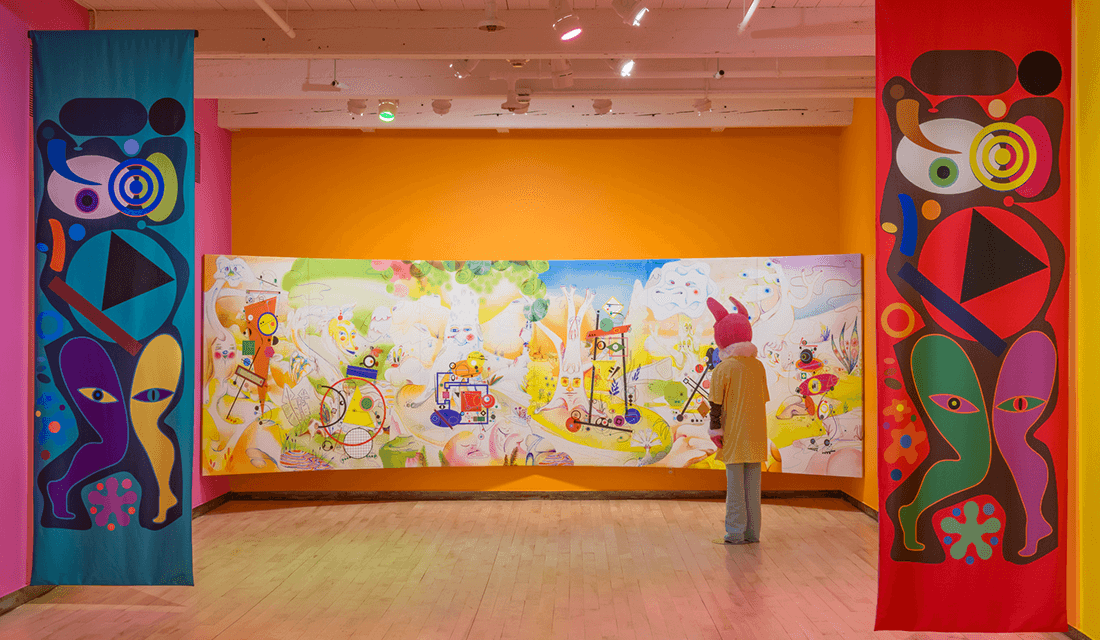

In this piece, editor Nora Rosengarten talks to curator Isabel Casso and artist Ad Minoliti about Minoliti’s new exhibition at MASS MoCA in North Adams, MA. Curated by Casso, Fantasías Modulares features Minoliti’s enigmatic work in the artist’s first North American solo show.

Hi Isabel and Ad, thanks for making the time to talk to us!

To start, Isy, how did you find out about Ad’s work?

Isabel Casso

It’s a question I’ve been getting a lot lately — I actually met Ad in Mexico City a few years ago.

Ad Minoliti

I wasn’t famous or anything! [laughs]

Isabel Casso

We met through a mutual friend, someone I met through my brother.

Ad Minoliti

I like that it’s a family connection.

Isabel Casso

Me too. And at the time, actually, Ad was working on a series with her mother. The series was trying to push back on the conventional narrative of male genius, in which the father teaches his sons and artistic knowledge is transmitted through a patriarchal lineage. This is such a dominant narrative in conventional art history, and I liked that Ad was questioning this approach. From there, I began to follow her career and fell more and more in love with her practice. It seemed natural, then, that when I had the opportunity to curate an exhibition at MASS MoCA, I chose Ad. Also, it’s a particular pleasure given that this is her first.

Ad Minoliti

It’s my first institutional solo show in the States!

Isabel Casso

Congratulations!

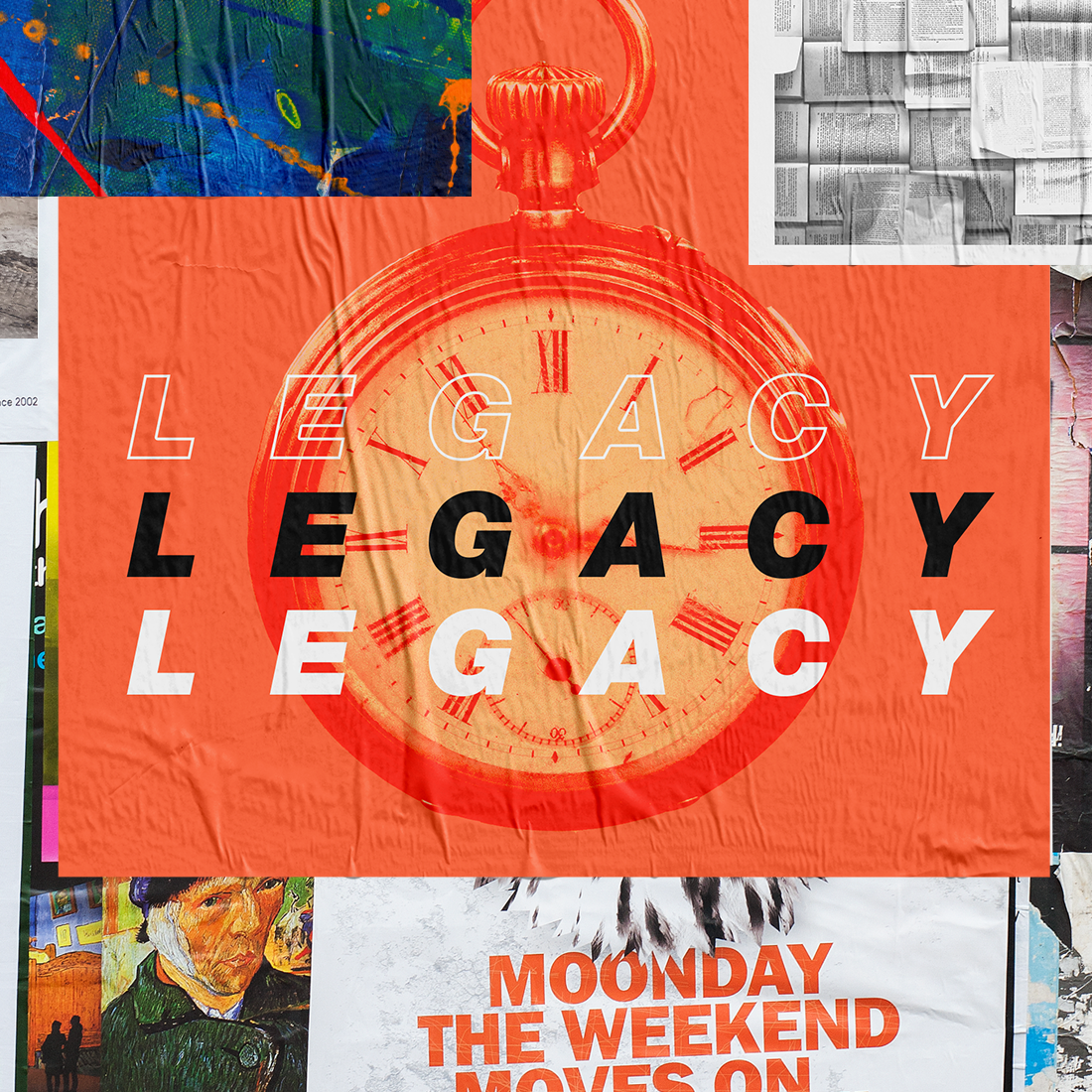

Installation view of Ad Minoliti: Fantasias Modulares | Source: © Kaelan Burkett/MASS MoCA

Yes, congratulations!

Ad, have you worked closely with curators like this before?

Ad Minoliti

It depends a great deal on the people and the unique relationships you build with them. The relationship with the curator is very important, because they take care of so many things… For example, working with Isy has allowed me to work in a country that I am not from.

Portrait – Adriana Minoliti | Source: Enguerran Borter/YouTube

Isabel Casso

Susan Cross — who is the Senior Curator at MASS MoCA, and also my supervisor and mentor — said something that has stuck with me. She said that curators are the midwives of contemporary art. You bring something into reality; it might not be your vision initially, or your idea, but your job is to help it along on its way. The curator is able to draw attention to an artist, to their work, and there’s a lot of power in that.

An example of this facilitation is the curtains, you know, [turns to Ad] you sent me the designs for them, but then it was my job to look at the colors, and figure out what kind of fabric would be best, etc. The logistics are all in service of your vision which becomes our joint vision.

Installation view of Ad Minoliti: Fantasias Modulares, featuring Landscape | Source: © Kaelan Burkett/MASS MoCA

Ad Minoliti

In that way the curator is also a producer.

On that note: how much of the work in the show is new work? Did you create pieces specifically for this exhibition, or did Isy select from existing pieces?

Ad Minoliti

It’s all new except the video!

Isabel Casso

Yes, all new work except for one piece. The gallery where the show takes place is pretty intimate, and so it becomes a kind of immersive environment, which I thought would suit Ad’s work.

Ad Minoliti

I remember — from the beginning, you always said you were interested in landscape.

Isabel Casso

Yes, she has this piece called Jungle from 2012. It’s a multi-paneled work depicting jungle scenery with Ad’s geometric characters interspersed among the foliage. I was drawn to this painting because it demonstrates Ad’s interrogation into nature and environments. It is easy to forget that “nature” is just as constructed as urban cities consequently making it inviting to some or, more often than not, unwelcoming to many. One of the things I find most compelling about Ad’s art is the ways she forces us to look more closely at the narratives we tell ourselves — and especially those we tell children — and think about what belief systems, assumptions, and prejudices undergird them. As a result, it felt important to begin an interrogation into fairy tales and children’s stories with the quintessential scene of a forested landscape. Ad created the sprawling Landscape as the foundational work of the exhibition.

Source: Ad Minoliti/Instagram

Ad Minoliti

For the past three or four years I have been working with childhood aesthetics — toys, dollhouses, coloring series, etc. All the things that we associate with children and childhood, I understand them as not just neutral materials. They teach us how to fantasize, but at the same time, they limit and dictate the characters of the fantasies we are able to have. That is, the dollhouse tells you how to live — get married, have kids and a dog and cook food in the kitchen — but at the same time it is magical, because these houses can be folded open and closed, we can move all the pieces around and change everything very easily. The family that the dollhouse portrays is very specific, and so what I want to do in my art is to take that same device and twist it to comment on other ways of living, other possibilities.

Isabel Casso

I think your phrasing of that is really important: “learn to fantasize.” This is so counter to the way we imagine fantasies. We’d like to think of them as spontaneous and free, but often there are very literal correlations between our fantasies and the oppressive systems in the world. For example, science fiction…

Ad Minoliti

Yet so often even in imagined worlds we find racism, homophobia, sexism, discrimination on the basis of age. And this is supposed to be a fantasy, a place where anything is possible.

I hear you both using the word “fantasy” in two different ways. Some kinds of fantasies are pre-packaged — they come to us from society and we consume them. But then there’s the possibility of a fantasy beyond those ones, something that really springs forth from the individual and is a reflection of desire and imagination and potency.

Yes, I think personally I am coming from a place of dissatisfaction with the former. What I see is not enough, and so my work explores other ways.

Source: Ad Minoliti/Instagram

Isy, are there things you’ve learned from curating your first exhibition?

I think all the time about how good curatorial work feels frictionless — the success rests on making your labor invisible. So I’m curious to hear how this experience has been for you.

Isabel Casso

I’ve worked in museums for a while now and one of the things I’ve learned is that it takes so much more than one person to put an exhibition together. The exhibition is the result of countless people from various departments. Just this past week as we have been installing, the Art Fab team and the Building and Grounds team did an unbelievable amount of pre-work for this show. We’re currently three days ahead of schedule because of all their hard work. It’s incredible.

I also think you’re right — when something is well done it appears or is deemed “effortless” which erases the labor. For example, writing exhibition text takes so much time and thought and effort. The text for this exhibition was written through collaboration with my coworkers, friends and peers, and their feedback was essential. I think the arts needs to move away from the idea that only a few individuals make an exhibition — it requires so, so many people working together.

You mentioned the text that accompanies the exhibition. I know it was incredibly important to you that there be a chapbook with essays from a number of art historians about Ad’s work.

Why was that a priority for you?

Isabel Casso

Yes, I had the idea that we should make a chapbook, even though this isn’t something that has traditionally been a part of these exhibitions. Eliza Harrison, Emma Jacobs, Jonathan Odden and Helman Alejandro Sosa have contributed to this exciting project. This stemmed from my belief that no one — or even two — people have a complete understanding of this art. I wanted to include many different perspectives as a way to nod to the diversity of interpretations.

I think especially in a show that is grappling with so many big ideas (childhood, queerness, futurity) having so many different voices gives the curatorial gesture a multivalence that compliments such complex ideas.

Yes, absolutely. And it’s important because even Ad and I have grappled with the meanings of different words in the context of her work. For example, the word “future” is one we have talked about a great deal. It was contentious — I see it along a scholarly line, as emblematized by José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: the Then and There of Queer Futurity and also reflected in Jack Halberstam’s scholarship on queer failure. Whereas Ad really thinks that the word “future” is a linear idea that continues a prescriptive, normative timeline that she wants to escape.

Ad Minoliti

I think a part of my resistance came from experience in Spanish. In other times, when the word “future” was used to talk about my work, it was a way to say that my work was about an idealized or pacifying fantasy, a fantasy of escape, rather than actually invested in the present and in a nonhuman timeline. I want to be clear that I am offering an alternative or parallel universe, one that could be happening right here and right now in a non-human dimension. And in that sense I don’t see the word applying to my work.

Source: Ad Minoliti/Instagram

I think what you’re both pointing too is one of the challenges of art criticism: How do we talk about art that is challenging the status quo? What language can we use to consider art that is invested in deconstructing the terms we are accustomed to?

I don’t have answers, but it is fascinating to hear you both share your perspectives. I can imagine, for you, Ad, as an artist, it must be frustrating to create work that you understand to be challenging these notions, and then to hear it critiqued in terms that reflect the very conventions you’d like to defy.

Yes, and I think it’s exacerbated by the fact that my aesthetic is one of childhood. Because so much of my work is preoccupied with youthful and playful imagery, I think that can sometimes be interpreted as a sign that I am not invested in these big ideas, or that I am not serious, but that is the very same prejudice I want to fight.

AD MINOLITI: Museo Peluche – Entrevista con Carla Barbero y Marcos Krämer | Source: Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires/YouTube

Absolutely. I’m sure you also encounter media hierarchies and the assumptions that come with “lower media” like cartoons or comic books.

Yes, I think this also has to do with the way we are taught to understand artists. People like to look through my work and search for references to the “geniuses of art history” as a way to legitimize my practice. And to be honest, I would prefer that my work be compared with Steven Universe than with [Wassily] Kandinsky. That feels more honest and productive.

Isabel Casso

Even when people walk through, one of the comments we hear a lot is: “Kids are going to love this exhibition.” And they are. But I think that it’s important to remember that adults will also be able to take a great deal away from this show. I find that assigning art to an age range is so limiting.

Yes, and such an assumption also ignores the power of childhood.

Ad Minoliti

I’m interested in the way that society wants to box things off from one another, and so often these divisions are on the basis of age. We want to restrict certain kinds of things as “only for kids” and other categories of things as “for adults,” when, it seems to me, these are arbitrary distinctions. This is one of the things I learned from studying queer and feminist theory: we have to investigate desire and play, and think about why we want the things we want and really challenge some of the assumptions and perceptions that come with what we are taught.

Source: Ad Minoliti/Instagram

I can’t wait to see the exhibition!

Thank you both so much for your time!