MEGAN DOMINY

If your Facebook feed looks anything like mine, playwright intent/consent has been a very hot topic lately. Maybe your Twittersphere has been focused on the other political dumpster fires in the news though; in which case, here is the list of controversies regarding playwright authority that you’ve missed: Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Stephen Adly Guirgis closed a production of his play The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, serving a cease-and-desist order during the show’s run after learning extensive cuts were made without his permission. Shortly after, furor erupted online when Edward Albee’s estate denied a company the rights to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? because a black actor was cast as Nick. To complete the trifecta, angry accusations of “whitewashing” an Australian production of In the Heights prompted the producing organization to cancel the show. These notorious and highly public incidents have sparked debate on the extent to which a production should serve the playwright’s original vision.

Shelton Theater’s production of The Last Days of Judas Iscariot that got closed down | Source: © Richard Ciccarone/SF Chronicle

Richard Ciccarone, the director of the closed Judas Iscariot production, defended his production’s “transformation” of the script with a program note that read:

“For me, a play is a living document that should transform from production to production. It is something the author bestows upon the public as a gift to be shared… The play may not be what the author intended in his original vision, but as a work of art. I believe it is our duty to interpret and not simply repeat, to participate, not just transmit, and by doing so become a collaborators [sic] in the work.”

When I read this, initially I thought it sounded reasonable. Theatre is, after all, a collaborative art form — perhaps even the most collaborative of all art forms. Shouldn’t each production be allowed to give the show its own “stamp?” After a show has been performed literally millions of times, don’t we have an obligation to find a new way to tell that story, or let it wither away to skeletal remains in the canon?

As both a playwright and an actress, I cannot answer “Yes!” emphatically enough. I absolutely feel that each group of artists approaching a script should find their own expression of the play’s story. However — and this is an important caveat — artistic expression does not give a production carte blanche to do whatever they want. It is incumbent on the artists to tell the story that exists in the script.

The story is the lifeblood of a show.

From a simple legal standpoint, the script itself is protected intellectual property. Like any other copyrighted work, it belongs to the person who created it. Producing a show requires applying for and being granted the rights, i.e., receiving permission from the playwright to use their work. Copyright laws provide playwrights with some very basic protections, such as the show will feature the playwright’s words, as they were written, in the order they were written. Seems like a silly premise; one would inherently assume that if a company invested time and money for a playwright’s words, they might want to actually use them, right? Surprisingly, the answer is “not always.”

Whether it’s been as a student/teacher, auditioner/auditionee, or involved in a reimagined Shakespeare classic, most theatre “lifers” have been guilty of some level of script adaptation. High schools replace perceived “bad” language (“God damn it” might become the less offensive/less effective “Gosh darn it!”). When creating a monologue, actors might cut other character’s lines or their own internal lines, to streamline into 90 seconds of material for an audition. And I couldn’t even try to count the number of Shakespearean productions that have been squeezed, grated, and smashed into a director’s conceptual pulp. And that’s fine. These textual indiscretions are perfectly acceptable on their own because these performances have an inherently different purpose from a professional production of a copyrighted script.

An example of taking big risks: old person makeup | Source: © Bryont.net

Educational environments exist to teach. Hopefully, this process creates some great art along the way, but it should also fail freely. Students should be allowed to take big risks and suffer big falls without critical reviews or box office revenues to fret over. They should be encouraged to bite off more than they can chew, and beef their artistic mandible up in the eating!

Auditions are another strange beast in the theatre world that often require a script adapts to the format. Like educational theatre, an audition monologue has a unique purpose. It is designed to showcase the performer. It is purely functional. It gives the auditioner a chance to sample that specific actor’s brand — how they sound and move onstage, the instincts they have, the choices they make — and possibly, if they can take direction. But achieving a grand, soul-touching theatrical experience is a bit much to ask of 90 seconds, no matter how well they are crafted.

The professional practice of theatre is different. First, it opens the playwright to scrutiny by critics and reviewers. As the writing is attributed to one person, the playwright will bear the accolades or condemnation for the actual script alone. Particularly for a new work, this can be monumental in a playwright’s future success. For this evaluation to be accurate and fair, the show must be true to the text. The words on the page represent a playwright’s contribution to the production as much as the clothing reflects a costume designer’s. To cut or change text without permission would be as egregious as an actor deciding to wear jeans onstage instead of his assigned doublet and hose. How can we possibly evaluate the work if it is not present onstage?

Obeying the basics of copyright law by speaking the script as written shouldn’t be a discussion at all. Far trickier is wrestling with the idea of approaching a show with “a concept.” I love the definition of the word concept: “something conceived in the mind; an abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances; A plan or intention.” It so perfectly captures the nebulous nature of applying a concept to a show. This is where theatre struggles to balance creativity with faithfulness to playwright intent. How do we avoid presenting the same show time and time again? How do we transform a classic into a performance that relates to the world we live in now?

A truly great piece of theatre doesn’t need a sparkled concept to remain relevant. Great stories are great stories because they connect with us on a basic human level. They speak to our humanity and our truth. They continue to reflect a reality we recognize, and we continue to learn from them. In fact, imposing too much concept on a piece can have the opposite effect. It can limit the story’s universal appeal and muddy the themes.

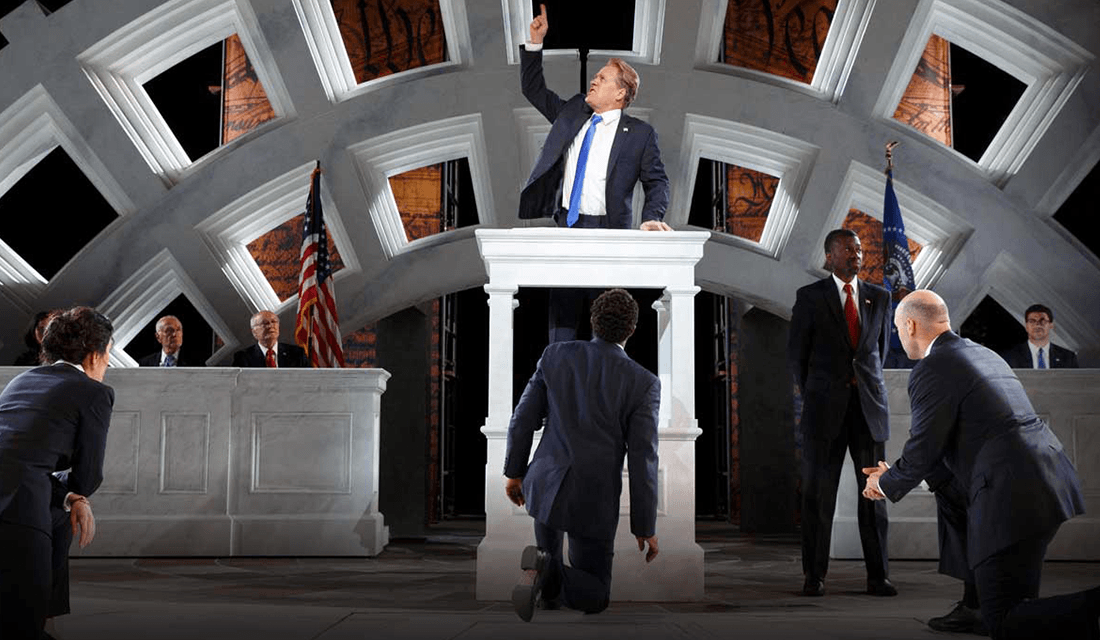

Public Theater’s 2017 production of Julius Caesar | Source: © Public Theater

Take the Public Theater’s summer production of Julius Caesar. An actor who looked and sounded like our own Commander in Chief played Caesar, who, of course, is stabbed to death fairly early in the play. While the show attempted to address the dangers of forgoing democratic institutions in the name of “resistance,” the attempts were greatly overshadowed by the controversial image of the current president being assassinated. Corporate sponsors pulled out. Protests regularly disturbed performances, as many misconstrued the play’s message as one calling for violence rather than warning against it.

Could the same parallels have been made more subtly without the Trump and Melania impersonations? Of course. They were there all along, embedded in the text. The script remains relevant because it contains so many truths about power and revolution. Ultimately, the concept overpowered the play’s message because of a lack of faith in its story.

I’m not advocating for cookie cutter productions or claiming that shows can only be done traditionally. There are many ways to transform an old script with a fresh perspective while still honoring the playwright’s intent. Choices can be bold and inventive, provided they answer a simple question: Does this support the story?

The words on the page represent a playwright’s contribution to the production as much as the clothing reflects a costume designer’s.

The recent Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s classic A View from the Bridge is one of the best shows I’ve ever seen and is a great example of how a concept can subvert a playwright’s initial vision, while actually enhancing their intentions. Walking into a show traditionally staged as a realistic “living room drama,” an audience expects the set to resemble a small New York City apartment.

The 2015 Broadway revival of A View from the Bridge | Source: © Jan Versweyveld/Howlround

Instead, the audience enters an almost blank stage, sitting on all four sides of what appears to be a cage fighting ring. The traditional climax of a gunshot is replaced by a stylized image of all of the characters tangled and grappling in the center of this fighting ring, showered in red blood from a spout over them. While the image is stylized and not played realistically, it absolutely communicates the gunshot’s horror and literally bathes the characters in the blood they’ve helped shed. It is both original in production and faithful to the script. Arthur Miller’s story is still being faithfully told, in an inventive and distinct way.

How do we avoid presenting the same show time and time again? How do we transform a classic into a performance that relates to the world we live in now?

For me, it always comes back to story. The story is the lifeblood of a show. When I approach a script as an actor, I think of it as my coloring book. The story’s sketch already exists. My job is to create the colors and brushstrokes that will bring my character to life. The images are there, waiting for everyone on the creative team to color their section and complete the portrait. No one needs to redraw the lines if the image is one worth illuminating in the first place.

Theatre requires an unbelievable investment of time, talent, and money. It combines visual artistry, sound, choreography, and performance — so many creative people contribute to the final product. The script should excite the entire creative team to rediscover the way it is performed without resorting to clever fixes. Choose the show that moves you to your core, the story that begs to be told. If the project inspires its creators with that type of fervor, it might reach the zenith of theatrical experience, to which we practitioners aspire: to tell a story that connects with our audience at their core, touches their humanity, and leaves us all changed as we exit the theater.