SWEDIAN LIE

In this issue we talk to American linguist Marc Okrand, an expert in dead American-Indian languages and famed for creating the Klingon language for the Star Trek series as well as the Atlantean language for the Disney animated movie Atlantis: The Lost Empire. We caught up with Okrand as he’s preparing for an annual trip to the Klingon Language Institute, and talked about linguistics, languages, communication, and, of course, a bit of Klingon.

Hi Marc, thanks for making the time to do this interview!

What drew you into studying languages in the first place?

Marc Okrand

It was an accident! When I was in college [in University of California, Santa Cruz], the first course I took was a course [that] everybody had to take and it was called something like “Language, Culture, and Society.” I didn’t know what [the course] was supposed to be like, but it turned out to be… What it turned out to be was really good. It was an introduction to the faculty and to the different disciplines, all centered around talking about language, and of course [in a class called] “Language, Culture, and Society” there’s nothing that cannot be included in that — including physics! So there was a lot of things to talk about.

But the first week and the last week was about linguistics. I’ve never heard of linguistics before, I didn’t know what it was, but [of] all the different topics, that was the one that was most interesting to me.

In the summer before sophomore year, [the school has] revamped the entire program in linguistics and the course I was supposed to take no longer existed. So [the school] set up an independent study, just [between] me and the professor, to talk about the stuff I didn’t get because of the way they remodeled the curriculum, and I think that’s what hooked me to linguistics. It was working one-one with him, with real data that he had, and not just studying textbooks.

You’ve been studying languages for more than 30 years now.

How has linguistics, or the study of languages, changed over the course of your career?

Marc Okrand

Noah Chomsky | Source: Wikimedia Commons

It actually started changing in the beginning of my career because I’m sort of the last of the old-school way of thinking about [linguistics]. This was all 40 to 50 years old. When I was in college and graduate school, it was when the Chomskyan revolution was just getting going. He was very popular and influential, and new at the time. The tradition that I came out of was the Berkeley tradition, which is where I went to graduate school.

For years, the people that have been going to the [Berkeley] linguistics program had all done fieldwork. They would learn a language by sitting down with the speaker of the language — usually a language that, until then, had not been a written language and has not been studied very much — and asked, “How do you say this, how do you say that,” and figure out how to write a dictionary and that sort of a thing. It was very much a data-oriented approach and the way they would describe the language was also very data-oriented. Of course, there was a theoretical bent to it, but the point was about [building] good data that people can use in different ways. What [was] ‘short-thrifted’ in all this was the syntax. So coming out of MIT, where Chomsky taught in the East Coast, was this whole new way of thinking about and talking about language — generative grammar, generative syntax, generative phonology, and so on.

What changed was that the orientation of linguistics moved from a heavy concentration on data to a heavy concentration on theory. I’m more on the data side of thinking, because whatever your theoretical orientation, you can use the data — but it doesn’t work the other way around; whatever data you’re working with, you can’t necessarily use the theory.

I know people who do linguistics now and I don’t know what they’re talking about. I’ve seen their work — and it looks like math and is very interesting philosophically — but what I want to know is how do you say this in this language, how do you communicate this concept in a different way than how we do it in English, French, and so on.

Do you think these two divergent methods of thinking about language and studying them are limiting our understanding of linguistics and how we communicate with one another?

Marc Okrand

They are two different traditions but it’s [still] the same thing: you’re talking about languages and the reason you’re looking at them is [still] to see how they work and how grammars work and so on.

People have said to me, “What good is all this?” and there are a couple of answers. For me, one of them is [the same answer to] why do you study history? It’s the same reason: it’s to see how things work and how things changed so that you can see how things are going and put them in a context.

In the case of language in particular, it’s also about a way of opening your mind. If you speak one language, you sort of only have one way to look at the world, and you don’t realize that until you learn another language — that there are different ways of organizing things and talking about things, and you start seeing things differently.

Klingon enters into this because it’s a very limited language — it doesn’t have much vocabulary, it’s only 3000 words, which is not a lot.

And it’s mostly about warfare!

And it’s mostly about warfare, right! People have translated all kinds of things into Klingon. They’ve translated Shakespeare with this limited vocabulary and grammar. How do they do that? Some people get frustrated because there’s not enough vocabulary [in Klingon], but other people find it fascinating and challenging and interesting, because you have to deconstruct the original and reconstruct it into Klingon in a different way, which gives you all kinds of insights, not so much into Klingon, but into the original language, the original thinking, and the original author.

What a perfect segue! Let’s talk about Klingon, the language you created for the Star Trek series.

How did it all start?

Marc Okrand

In the original Star Trek TV series, which was on in the 1960s, there was never any Klingon language. There were Klingons, but they never spoke their own language; everybody only spoke in English. No matter where the crew of the Enterprise went, traveling the galaxy in these strange, unexplored planets — lo and behold, everybody speaks English! It’s amazing!

So the first time you actually hear the Klingon language is in the first movie, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, which was [released] in 1979. The very beginning of the movie is Klingon language. You see inside the Klingon ship and this guy is barking out commands and there are subtitles — that’s the beginning of the language. The guy who made [all] that up is an actor named James Doohan, who played Scotty. He’s not the actor who speaks it, but he made it up. And what he had in mind was to make up a language that sounded weird and alien and ‘spacey’ and stuff like that. This commander or captain of the Klingon ship had to sound like he was giving serious commands, regardless of what he was [actually] saying.

The next time the Klingon language was heard was in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock [released in 1984], and that’s what I did. I based what I did initially on what Jimmy did, because it had to be the same language. When I did it [in Search for Spock] I had the script, so I knew I had to make up Klingon lines that meant whatever it said in the script, and I only made up enough grammar and vocabulary to satisfy those [requirements]. So I likened what I was doing to the guy who builds movie sets or props.

Klingon Commander Kruge discovering the plans for Project Genesis, in Star Trek III: Search for Spock | Source: © Memory Alpha Wikia

If you’ve ever seen a movie set, the part that’s on camera looks really good, but behind it, it’s ridiculous — and off to the side, it’s ridiculous! It’s [all] held up by wood and strings! There’s a door, but it doesn’t open! But it serves the movie — it wasn’t built to serve as a real house or a spaceship, it was built for the movie or the TV show or the play. When I designed the [Klingon] language initially, it was the same thing. I made up a whole lot more than what ended up in the movie, but I didn’t make up anything that wasn’t in the script. I had to think about how the whole system worked, but if no one ever said anything involving second person plural [for example], I didn’t make that up. There was a slot for it, but I didn’t make it up because it wasn’t needed. Initially, I never thought I was making a language that people were actually going to speak. I thought I’m making a set, or a prop, or a weapon — if you pull the trigger on this prop weapon, nothing happens, but it looks cool! And that’s what I thought I was doing.

Source: Amazon

What then happened was, while we were filming Search for Spock, the filmmaking crew would come up to me from time to time and say, “Hey, you’re the language guy, right? Say something in Klingon!” So I’d say, “What do you want me to say?” They’d say, “Say hi!” “A Klingon would never say that!” I said. And they laughed and so on. Anyway, I started thinking that if these filmmaking people are interested in this language, maybe Star Trek fans would be interested in it too. So I got the idea of writing a book explaining how the language works [The Klingon Dictionary, published in 1985]. When you write a book you hope that people would buy it — otherwise, why do it — but I honestly thought that it’ll mostly be a book that would sit on your coffee table and you’d glance at it from time to time, and that was it. But I was wrong.

People bought the book, and read it very carefully and studied it and started learning the language and started compiling a list of all the typos — and a language speaking community started to develop.

What do you think made this organic development of an ‘inorganic’ or fictional language possible?

Marc Okrand

I think it was because of two things: one is that this language is connected to Star Trek, and the other one is that — during the same time this was going on — the Internet was [just] getting going. And what that mean is that people could find each other.

Prior to the Internet, people were interested in various things and they might have some friend in town who’s interested, but that’s it. Now, with the Internet, they can find people all over the country and the world who are also interested, and they can talk to each other. And so these organizations started forming, initially online and eventually in person. This Klingon Language Institute that I’m going to later this week, this has now been going on for 25 years! A lot of people have become really good friends and marriages have happened in Klingon! There are speakers who are absolutely fluent in the language and people who are just fumbling around and everything in between!

Source: Klingon Language Institute/Facebook

I think this would all not have happened if it weren’t for the Internet. They wouldn’t have found each other, in these numbers. It’s not like Esperanto, where the goal was to get people to use it — the goal of Klingon was a piece of scenery where the door didn’t work. It was very different.

Do you see any parallels between how Klingon, a fictional language, developed and how a natural/real language would have developed?

Marc Okrand

It’s different because of [Klingon’s] current development is very constrained, by me. That’s not my choice — the Klingon-speaking community has decided that they will make up no new grammar and no new vocabulary; they’ll [instead] turn to me. They’ll pose the questions, but they’ll turn to me for the answers. And I’m very sluggish about getting the answers to them.

The reason they did that is because the Klingon-speaking community is so small [that] if they didn’t do it like this, it would very soon fragment in a way that [would mean] people wouldn’t understand each other. If the community was much bigger, you’d get dialects and things — and that’s fine because there would be enough people to support that — but when the community is so small, it’ll lead to arguments rather than dialects. In that sense, the growth of the language is very, very different from a natural language.

It’s also partly because — with one exception that I’m aware of — nobody speaks Klingon as a native language. Everybody’s learned it as a second language, probably as an adult. And learning a second language, as you know, is very different from learning your first language or languages. You can grow up in a multilingual community and have two or three native languages, but that’s a different thing from learning a language later on. For Klingon, it’s only learning it later on. So the people who are more rigorous about [the language] say that since we’re teaching this to people, we want the rules to be straightforward and regular as can be.

You said “with one exception” — can you elaborate?

Marc Okrand

There was one kid that was brought up to be bilingual in Klingon a bunch of years ago. His father was a Klingon speaker; his mother was not. This guy [d’Armond Speers] was a graduate student in linguistics at Georgetown University and, as a linguist, he wanted to see if Klingon can be acquired — as a natural language is — as supposed to taught, as a second language is. So he didn’t teach the kid Klingon — he spoke to him in Klingon. And the kid grew up as a bilingual baby!

The way that the father realized that all this was really working was… I’ve never made, in all the vocabulary I’ve made for Klingon, a word for “baby bottle.’ So [the kid] couldn’t say that [in Klingon]. I did make up a word that means a drinking vessel of any kind — so a regular glass or a beer stein or a wine glass, it’s all the same word [HIvje’]. The father would use that word in the house. One day, the father said to the kid, “Go get your drinking vessel,” and the kid went and got his baby bottle. The father had never used that word in reference to the baby bottle before, but [the kid] knew what it meant when the father said “your drinking vessel,” not “a drinking vessel” — so the kid knew which [one] his was.

After that, the father lost interest because he has proved his case and the kid also lost interest when he realized he was the only kid on the block that spoke this language and his father also spoke English, so there’s no real need for it anymore — the novelty wore off. The kid’s now in college, I talked to him actually the other day; he’s fine, everything’s okay.

Does he still remember Klingon?

No, no. He stopped speaking it when he was 3 or 4 years old, and the father stopped speaking it [to him] too.

Your description of Klingon as “this piece of scenery where the door didn’t work” makes me wonder:

If someone, someday, stopped making Star Trek, would Klingon survive? Would it continue?

Marc Okrand

Now, yes. If you asked me this question 20 years ago, I’d say probably not. But now, yes.

It’s [because of] the speakers. If you go to these meetings and see how much fun these people are having — it’s great. You intellectually have a good time with it, but more importantly, you socially have a good time with it, and it’s building real human connections.

So long as speakers exist, so long as there is a need for the language, it’ll continue. A language always has to be practical, at some level.

Marc Okrand

To be used, yes. To be not just an artifact. There’s nothing wrong with language as artifact; reading Egyptian hieroglyphics is great. But that’s not a language that you can ever use.

If that’s the case, do you think this is how languages die — when they are no longer used?

Marc Okrand

There are lots of languages that never got recorded in any way and the last speaker has gone — so [these languages] are dead. If they’re going to be revived, there has to be a practical reason to do it. Linguists will study all this stuff and write books about it, but that’s not reviving by speaking. That’s not reviving a speech community. It’s like when people ask, “What’s the trick to learning a foreign language?” The trick is there has to be a reason to do it.

Aside from Klingon, you’re also an expert in dead languages, in particular those of American-Indian tribes in California.

If a language is so-called “dead” and nobody speaks/uses them anymore, why study them?

Marc Okrand

The reason why I study a dead language is the same as why [one] study history. The history of a people is very much tied up to the history of their language.

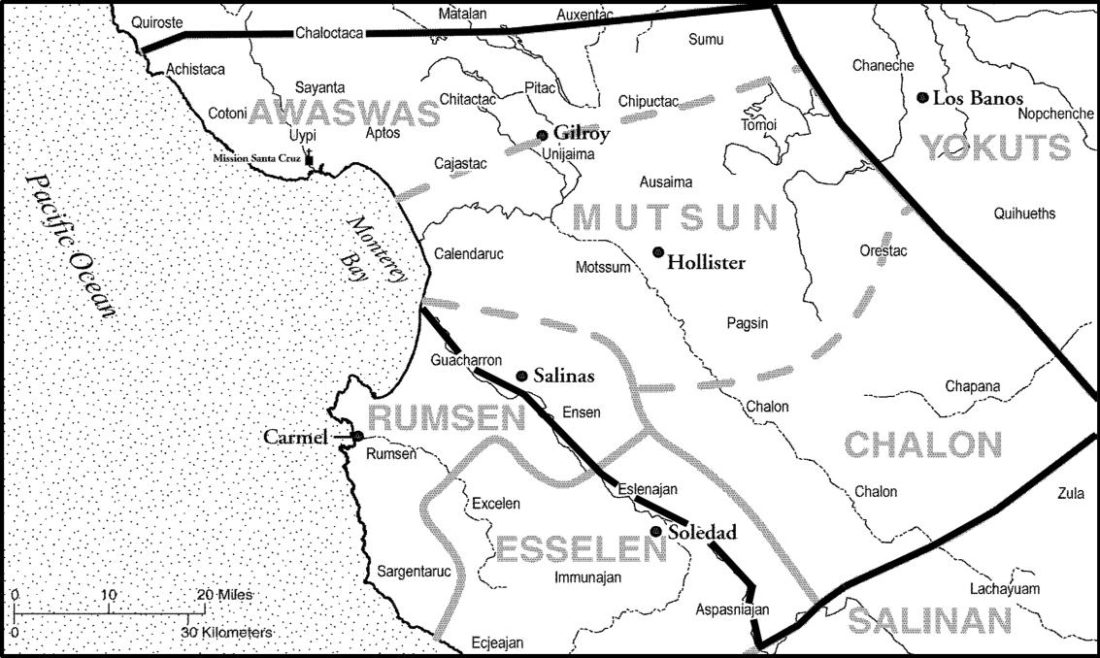

Mutsun Territory | Source: © Amah Mutsun Tribal Band

What happened with the language that I studied in particular, called Mutsun, was that at the time I studied it, there were zero speakers. The last speaker died in 1930. My work was based on manuscripts, primarily by one guy, an anthropologist [John Peabody Harrington] — his title was “ethnologist” but he was really a linguist, who worked for the Smithsonian for a long time — who wrote down all kinds of notes but never did anything with them. I went through a subset of his notes to figure out how [Mutsun] worked. With the advantage of these notes, I was able to come up with an incomplete grammar, a theory of a grammar — but I couldn’t come up to a speaker and [verify]. I can’t ask anyone any question and I’m at the mercy of the notes.

Now, saying that the last speaker died in 1930, that didn’t mean the people disappeared. They didn’t. Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, they started getting organized, and — on the basis of my work and other things, with the help of a couple of linguists, primarily one from Arizona — have started relearning their own language. And it’s working. The language is coming back. Slowly, and in a weird way, but it’s coming back.

They invited me to give a talk — this was 2-3 years ago — to the tribe about the work that I did on their language; they also wanted to know about Klingon (laughs). At the beginning of the talk, a woman gave a prayer in this language. And this is the first time I’ve ever heard the language. I’ve been working on this thing since 1970 or something, but I’ve never heard it because there were zero speakers — and now there is this woman who’s saying a prayer that she wrote in this language! It was beyond amazing. It was spooky. It was great.

I wouldn’t say it’s an ongoing thing or that there are lots of speakers of this [language], but it’s developing. There are people learning and speaking a language that everyone thought was dead.

Is there a language you wish you could bring back?

Marc Okrand

Amah Mutsun Tribe Members | Source: © Metro Active

Given what we’ve been talking about, the one language that I would love to bring back is Mutsun, which is being brought back, so I don’t know if that’s a cheating answer (laughs)! It’s happening!

What’s interesting too, at that meeting [with the tribe and the woman saying the prayer in Mutsun], was when the talk was over, the Indian people wanted to take pictures of me with them. There was one family that got together, and there were maybe seven people in the family, and one was a little kid who was maybe 10 years old or something who was not interested in having his picture taken. His mother said, “No, no, no, you come and be in this picture. You don’t know now, you’ll know later why this is important.” To have a picture with me. It’s not because I’m such a great guy, but because I did something that allowed them as a community to do something. That’s why it’s important. It didn’t have to be me, it could have been somebody else, but it happened to be me. The mother was basically saying that this is a connection to your history, to your past, to your family, to your tradition, and you’ll see why later when you’re older, why this is important.

What a lovely story to end on! Thank you so much for your time Marc, and have fun at the Klingon Language Institute!

Marc Okrand:

He devised the dialogue and coached the actors speaking the Klingon language heard in Star Trek III: The Search For Spock, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, and Star Trek Into Darkness. He also created the Atlantean language heard in the Walt Disney animated feature Atlantis: The Lost Empire. The Klingon language he developed has been used in a number of episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Star Trek: Voyager, and Star Trek: Enterprise. In addition, he created the Vulcan dialogue for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and Star Trek III, both Vulcan and Romulan dialogue for 2009’s Star Trek, and several languages for Star Trek Beyond.

He is the author of The Klingon Dictionary (Pocket Books, 1985; revised edition, 1992), an introduction to the grammar and vocabulary of the language; The Klingon Way: A Warrior’s Guide (Pocket Books, 1996), an annotated compilation of Klingon proverbs; and Klingon For the Galactic Traveler (Pocket Books, 1997), a guide to the finer points of the Klingon language, including specialized terminology, slang, idioms, dialects. He can be heard describing various aspects of the language and its effective use on the audio books Conversational Klingon (Simon & Schuster Audioworks, 1992) and Power Klingon (co-written with Barry Levine, Simon & Schuster Audioworks, 1993), both narrated by Michael Dorn. He also devised Klingon dialogue and contributed to the language lab portion of the computer game Star Trek: Klingon (Simon & Schuster Interactive, 1996). He did the translation for the Klingon opera ’u’ that premiered in The Netherlands in September 2010 as well as the expanded version of the opera’s story in paq’batlh: The Klingon Epic (Uitgevrij, 2011). He co-wrote the chapter on Klingon in From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages by Michael Adams (Oxford University Press, 2011), and contributed to the Klingon version of Monopoly and the instructional DVD Learn Klingon (EuroTalk, 2011). He is an associate producer of the forthcoming documentary film Conlanging: The Art of Crafting Tongues.

He has a B.A. in linguistics from the University of California, Santa Cruz (1970) and a Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of California, Berkeley (1977) and has conducted linguistic research as a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. His linguistic research has focused primarily on native languages of California, in particular the Ohlonean languages of the central California coast.

He is a member of the board of directors of the theater company WSC Avant Bard in Arlington, Virginia. For 34 years, up until his retirement, he helped manage the closed captioning of various network and syndicated television programs. In addition to his published work on Klingon, he has written articles on both linguistics and closed captioning for several journals and anthologies.