MICHAEL DONNAY

Before beginning, a brief note on language: Throughout this piece I use the terms ‘American Indians,’ ‘Native Americans,’ and ‘indigenous communities’ interchangeably so as not to privilege one designation over another. This is in an attempt to recognize that there is no definite preference for one term among tribes or scholars and that terminology is a matter of personal choice.

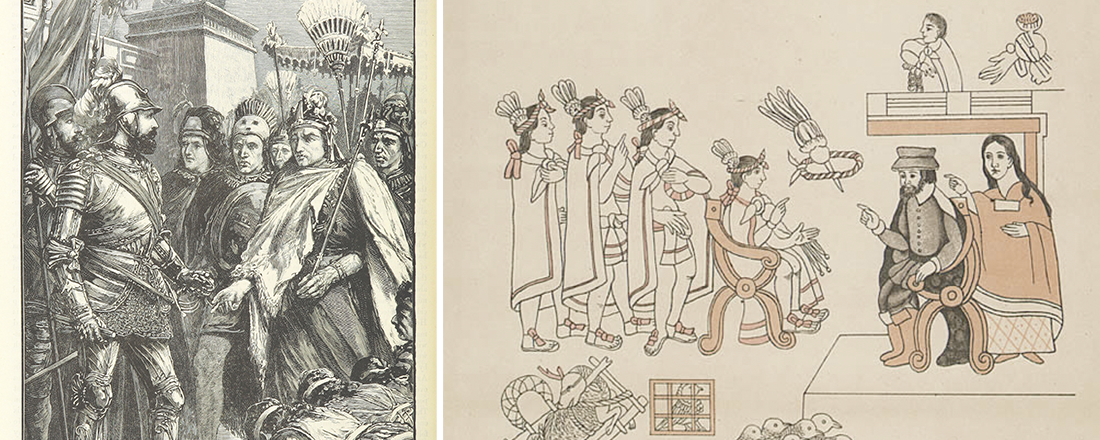

Arriving in Mexico in 1519, Hernando Cortés and the members of his expedition were amazed at the scale and scope of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital. Larger than Paris, then the largest city in Europe, the city boasted wide boulevards, crowded markets, and botanical gardens (a concept unknown to Europeans at the time). Elsewhere, Spanish soldiers were shocked when they encountered the Inca Empire — a polity that covered a quarter of a million square miles. At the time, the Inca had the largest road system in the world: over 24,000 miles stretching from modern-day Santiago to central Columbia. In the central Bolivian province of Beni, indigenous communities built a series of raised causeways and settlements stretching over 30,000 square miles that included transportation canals and raised agricultural fields. Further north, American Indians deliberately shaped the Great Plains into the vast grasslands we know today through regular, controlled fires in order to increase the population of elk, deer, and bison. And some scholars even suggest that large sections of the Amazon rainforest are the direct result of human intervention.

Two depictions of the fateful encounter between Spanish colonizer Hernando Cortés and Aztec leader Montezuma — the left by European artists and the right by Mexican Tlaxcalan artists | Source: The British Library/Flickr and Wikipedia

With such abundant evidence, it is clear that the Americas were home to many vibrant and established societies before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th-century. And yet, from Europeans’ first arrival on the continent through the mid-20th century, the accepted wisdom among historians and the wider public alike was that the “New World” was largely unpopulated prior to the great colonial empires of Spain, Portugal, France, and Britain. European writers regularly spoke of the Americas as empty, virgin territory waiting to be filled up. This assumption of emptiness retained its power in the United States well into the modern period. As late as 1910, a respected historian estimated that only 1.15 million people lived in the Americas before the arrival of Columbus — that’s less people than those who currently live in Philadelphia, spread across two continents! These attempts to minimize the native population of the Americas — which implicitly suggested that colonialism and imperialism were less egregious because there were not that many people to begin with — went unchallenged in mainstream scholarship until the 1960s.

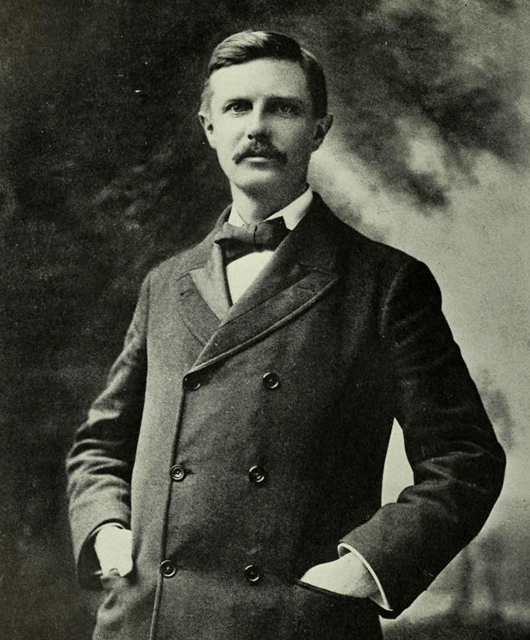

Frederick Jackson Turner | Source: Wikimedia Commons

But why did it take so long for this idea of an empty continent to lose its currency in the United States? In the 20th-century, at least, much of the blame lies at the feet of one man: Frederick Jackson Turner. In his seminal 1893 essay The Significance of the Frontier in American History, Turner argued that the westward expansion of the frontier was the formative experience for the American character. He wrote, “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” In his mind, American exceptionalism was possible because “they [American institutions] have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people — to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness.” In contrast to other nations, whose “development has occurred in a limited area; and if the nation has expanded, it has met other growing peoples whom it has conquered […]” the United States is a “different phenomenon.”

Turner’s emphasis on the role of the frontier and its inevitable expansion in the formation of the modern United States proved to have long-lasting impacts on the way Americans conceive of their history. The Turner Thesis, as it has come to be known, would dominate popular history for most of the following century. High school history textbooks — the vehicle through which most Americans receive their history — were particularly enthusiastic about adopting the Turner Thesis. It allowed for a narrative that was cohesive, while avoiding or minimizing less savory themes like slavery. However, in adopting this narrative Turner and subsequent writers did something else: they wrote 100 million people out of the story.

If we return to the language of Turner’s original essay, it quickly becomes obvious that his history erases a hugely important group of people. In his description of the West as free land and wilderness, Turner willfully ignores the hundreds of indigenous communities already living there. When he does mention American Indians, as to his credit he does later in his writing, they are not given the same agency or standing as white Europeans. So, although relationships with tribes like the Cherokee or the Iroquois are central to his conception of frontier development, Turner credits the skills and tools learned from them to the “environment” and not the people themselves. Indeed, in reading Turner’s work one gets the sense he doesn’t think the American Indians count for much at all.

[We] are left with an English historiography that has less evidence of a native presence compounded with an inherent bias against native communities.

As academic historians have moved away from this view in the last half century (and the popular view belatedly follows behind), the idea that the Americas were empty before 1492 has come to be known as the empty continent fallacy, the empty continent myth, or the pristine myth. Unfortunately, it has proven a decidedly difficult idea to get rid of — a standard American history textbook published as recently as 1987 describes the Pre-Columbian Americas as “empty of mankind and its works.” Given the glacial pace at which textbooks can be replaced, odds are that many Americans learned something similar in high school. So why has the empty continent fallacy proven so difficult to dismantle? It really comes down to three things: timing, public relations, and bad writing.

“…that He might make room for us”

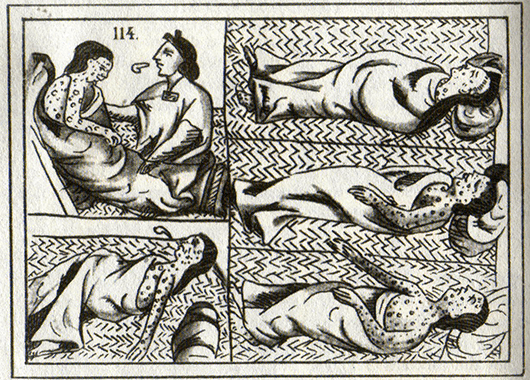

16th-century Aztec drawings of victims of smallpox | Source: Wikipedia

The English were late to the colonial game and they knew it. By the time they established their first permanent colonies at Jamestown (1607), Bermuda (1609), and Plymouth Bay (1620) the Spanish had been conquering and exploiting most of Central and South America for a century. Because they came late, the British (and, to a lesser extent, the French) experienced the tail end of what historians have called the worst demographic calamity in recorded history. Estimates place the combined population of the Americas prior to Columbus’ arrival in 1492 at somewhere between 20 and 120 million, with the consensus number being around 50 million people. By 1650, that number had fallen to around 5.6 million — a mortality rate of over 90%. Anthropologist Henry Dobyns, in his groundbreaking 1966 paper, argued that this staggering loss of life was the result of several waves of epidemics that were the result of European diseases: smallpox in 1525; typhus (probably) in 1546; influenza and smallpox together in 1558; smallpox in 1589; diphtheria in 1614; measles in 1618. Europeans were responsible — directly or indirectly — for the death of millions in a little over a century.

The Spanish were present to witness this devastation. The English arrived after the worst of the epidemics had subsided. That, combined with the less urban communities the English encountered along the Atlantic seaboard, created the impression among many English observers that the continent was far less populated than it had in fact been a few decades earlier. Indeed, records from European mariners who fished off the New England coast in the 16th-century recorded a thickly settled and well-defended coastline. Even the early Puritan settlers noted, in their typically self-centered and self-righteous way, “The good hand of God favored our beginnings [by] sweeping away great multitudes of the natives […] that He might make room for us.” But by the time more significant settlement began taking place in the latter half of the century, these memories of indigenous communities had already begun to fade. As soon as 1647, less than three decades after the colony’s founding, New England colonist William Bradford described the American continent as “unpeopled.” This literary erasure, compounded with the lack of communication between the scattered English colonies, further sped the disappearance of large indigenous populations from the public imagination.

European writers regularly spoke of the Americas as empty, virgin territory waiting to be filled up. This assumption of emptiness retained its power in the United States well into the modern period.

As British and French colonists pushed further into the interior of North America, they continued to encounter mostly smaller tribal groups. In contrast, when the Spanish conquistadores pushed into Central and South America they encountered complex and urban civilizations. Bernal Diáz, a member of Cortés’ original expedition that captured the Aztec Empire, made note of the numerous cities they passed through on their way to the capital of Tenochtitlan. Spaniards in South America were similarly impressed with the scope and complexity of the Inca Empire, even as they tore it apart in pursuit of gold and silver. Following these campaigns of conquest, the Spanish colonial project became one of occupation and accommodation. It accepted that an indigenous population would remain and the proliferation of government policies concerned with the treatment of non-Europeans resulted.

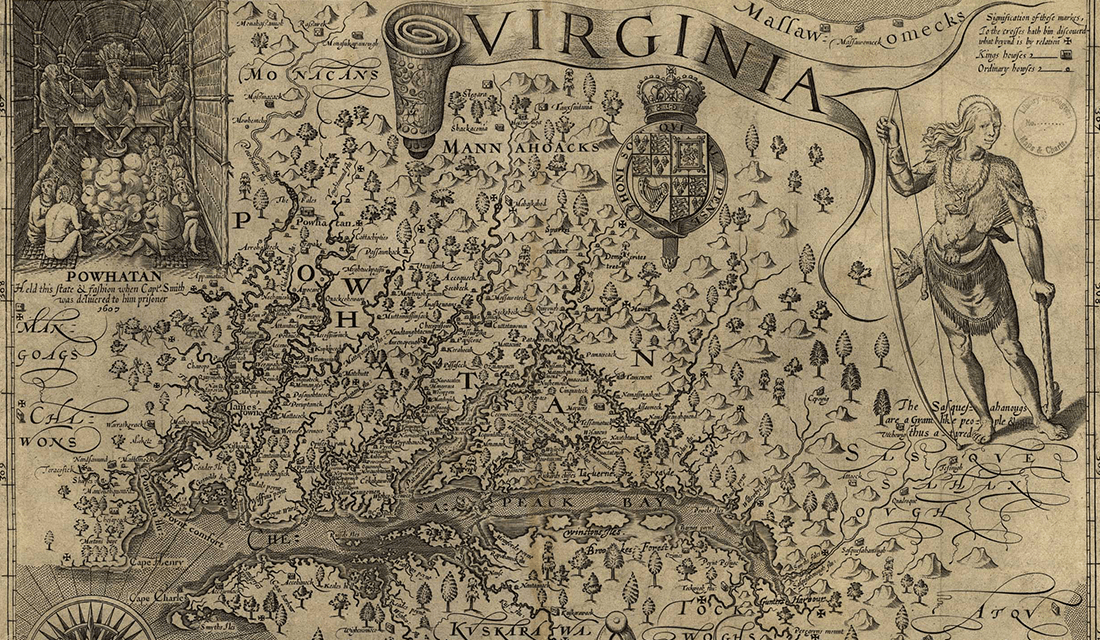

The British in contrast, since they encountered no such urban civilizations, did not find a need to accommodate indigenous communities into their colonial enterprises. At Jamestown, early British colonists encountered the Powhatan Confederacy, a group of semi-nomadic tribes who practiced agriculture but moved regularly when the land was exhausted. Although far more stable than the colonial establishment, the Powhatan villages had few of the markers of urban life that the British identified with civilization. As such, the colonists felt comfortable writing off the native communities as largely unworthy of consideration. When the colony began expanding in 1609, the Confederacy defended its territory and conflict broke out. This conflict would come to dominant relations between the British and indigenous communities for the next two centuries.

1624 copy of British colonist John Smith’s map of Virginia, depicting villages within the Powhatan Confederacy | Source: Wikipedia

Britain’s policy towards Native Americans became one of exclusion and extermination. They had different underlying motivations for colonization and a different economic and religious model than Spain, which contributed to their efforts to physically distance native communities from their own colonists. This attitude combined with the timing of their arrival to produce a historical tradition that largely discounts the role indigenous communities played in the Americas prior to the Europeans’ arrival. Most English-language sources deal with activities in North America, where native communities were less urban and more spread out and where evidence of anthropogenic land management less visible, and very little Spanish-language history made its way into the English-speaking world until quite recently. Thus, we are left with an English historiography that has less evidence of a native presence compounded with an inherent bias against native communities. In other words, ample ground for the erasure of American Indians from the historical imagination.

All told, it’s quite possible for the history a student learns in high school (often the last time they’ll seriously address the subject) to be entirely out of date.

It wasn’t just the historical imagination that found itself depopulated — this erasure had real social and political impacts for Native American tribes. José de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit priest, wrote an influential history of the new world wherein he ranked all of the civilizations of the Americas with Europe. Although deeply imbued with racial assumptions, Acosta’s work at least acknowledged that native societies belonged in the same category as European ones, even if they were in his mind hopelessly backwards. As a result of his writing and the work of others, a robust legal tradition developed in the Spanish colonies that, while it unequally oppressed indigenous communities, offered them a form of legal recognition within the imperial system. In contrast, English legal responses to American Indians developed in a context where their very existence was often denied. The theory of land ownership developed by John Locke, a British thinker whose writings had such a profound influence on the foundations of American political thought, was specifically designed to deny any type of political agency to indigenous communities.

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

1872 painting titled American Progress by John Gast | Source: Wikipedia

American history is a direct descendant of this British tradition, so it is unsurprising that in the historical void around native peoples the empty continent fallacy has sprung up. Its spread has been aided in the United States by the peculiarity of its national mythologies, namely: the idea of Manifest Destiny and the broader, expansionist impulses that guided American development through the 19th and early-20th-centuries. Coined in 1845 by a newspaperman advocating for the annexation of Texas, the phrase expressed the God-given right many Americans felt to control all of the land between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Although it is generally used to describe the period of expansion just before and after the Civil War, the impulse it identifies with is as old as European colonization in the Americas. The Plymouth Bay settlers famously viewed their endeavor as a religious mission to create a “city on a hill” to serve as a light to the rest of the world. Colonial attempts to push west over the Appalachian Mountains served as a major cause for the American War of Independence. Americans’ desire for territory in the south produced the Trail of Tears and the Seminole Wars in Florida. There was also the Mexican-American War, the Indian Wars, Seward’s purchase of Alaska; the list goes on.

There’s just one little problem with this expansionary impulse — which you might have guessed by the number of wars in the list above. People were already living in these places and weren’t particularly happy about being expelled from their homes (some of them for the third or fourth time in as many years). While many Americans throughout the 18th and 19th-centuries were unconcerned — some downright gleeful about committing mass genocide against hundreds of native communities — others were less so. But for the former, the comfort provided by the idea that (most of) the “future United States” was unpopulated allowed them to continue advocating for expansion while easing the moral burden of doing so. In short, expelling or killing thousands of people is a tough sell and it’s a lot easier to justify it if you say there weren’t (many) people there to begin with.

You Can Read About it in My Journal Article

Luckily, the type of history that could be used to justify such horrendous actions and allow for the erasure of entire civilizations is a thing of the past. The problem is that no one has told this to anyone outside of academia yet. Or, to put it more accurately, academic historians face a host of challenges in revising the public understanding of history. In large part, they themselves are to blame for this. Most academic historians develop a very specific specialization and write for other specialists, not the general public. Those who do publish for a wider audience are often near the end of their careers, so are somewhat removed from the newest developments in the field, or are just very poor writers — with some notable exceptions. (Readability is not often rewarded in academia.) What you end up with is, in effect, two worlds: academic history that becomes more nuanced but less widely read, and popular history that follows far behind those developments but enjoys a much wider audience.

This delay is compounded in primary and secondary education because of the time required to modify history curricula. Let’s say, optimistically, it takes 5 years for a new historical understanding to become widely accepted. History textbooks are updated every 3-4 years, so it could be almost a decade before a new development is reflected in publication. Once the new edition is produced the publisher needs to convince schools to purchase the new version. And schools do not replace their textbooks with great frequency, meaning it can take even longer for students to see those developments. Given the potential for much of American history to become politicized, some areas of the country can see an even greater delay. Since there is no national history curriculum — even the Common Core Standards only suggest competencies, not content — there is a lot of room for local variation. All told, it’s quite possible for the history a student learns in high school (often the last time they’ll seriously address the subject) to be entirely out of date.

In adopting this narrative, [Frederick Jackson] Turner and subsequent writers did something else: they wrote 100 million people out of the story.

And this lack of understanding is not purely an academic issue — it continues to have political implications to this day. The recent protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and their supporters are the only most visible example of treaty violations by the U.S. government. Native Americans have been battling state and federal governments, as well as private companies, for decades over encroachments on their rights as enumerated in over 300 treaties between the U.S. and American Indian Nations. In Washington state, 21 tribes sued the state in 2001 over fishing rights the tribes allege the state has violated. The Supreme Court agreed to hear an appeal in that case this month, more than a decade after the lawsuit. Along the Colorado River in Arizona and Utah, the Interior Department’s recent decision to shrink Bear Ears National Monument is expected to bring renewed uranium mining to the region. The Navajo Nation is still grappling with the effects of previous extraction efforts, including the 1979 Church Rock spill that released 93 million gallons of radioactive solution into the local groundwater. Because the impacts occurred on land held by the Navajo Trust, the tribe needed the governor of New Mexico to request federal assistance — he refused.

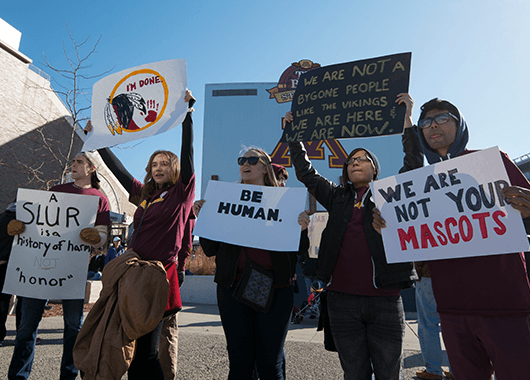

Protests against the racist mascot of the Washington, D.C. football team | Source: Fibonacci Blue/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Native activists and politicians believe that a better understanding of the United States’ relationship with and responsibilities to tribal nations would help ease these and other issues. Referring to the rights native peoples have within the U.S., Kevin Grover — the director of the National Museum of the American Indian — says, “These rights are not a gift. They are rights that are hard-won […]” Native American activists have been working to defend these rights through a number of different avenues, including efforts at education and legal action when their rights have been violated. The beginning of the modern native rights movement is often dated to the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz by 90 activists, and has continued with efforts such as the defeat of the Orme Dam project by the Yavapai Nation and the campaign against racist mascots in professional sports.

(Not) Empty of Mankind

Although it is difficult to say for certain, I think it is safe to assume that at this point the majority of Americans do not believe in the empty continent fallacy. Whether through the idealistic view promoted by our national celebration of Thanksgiving or the more nuanced understanding advanced by native activists, most people have some sense that societies existed in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans. Now the challenge is to deepen that understanding to include new developments and discoveries unearthed by activists, historians, archeologists, and anthropologists. Exciting new researching is revealing the impact indigenous communities had on their physical environment and other scholars are focusing on the contributions of the “New World” to the Old — after all, every Irish potato or Italian tomato originated in the Americas. By enriching our understanding of the Americas before 1492, we can better understand the United States’ relationship with the peoples and environments that predate it and what responsibilities we have for our history.