DELESSLIN GEORGE-WARREN

And yes, we’ll live to be much older, thanks / To popular consensus. Weightless, unhinged,

Eons from even our own moon, we’ll drift / In the haze of space, which will be, once

And for all, scrutable and safe.

– a segment from “Sci-Fi” by Tracy K. Smith

Insubordination

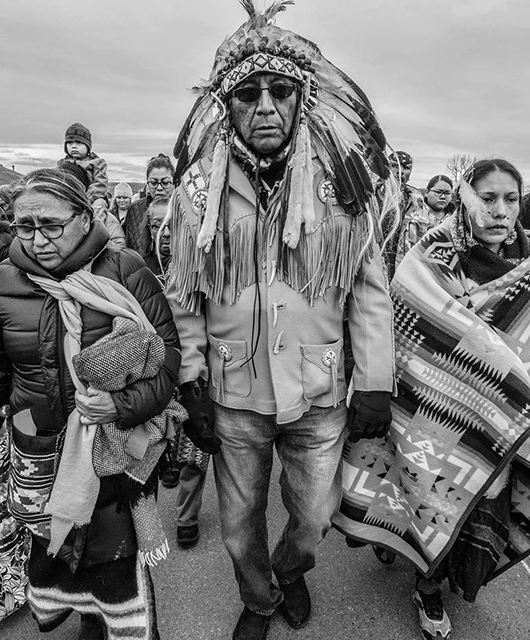

On October 24th, 2016, 141 indigenous peoples and their allies were arrested by militarized police in riot gear. According to the accounts of indigenous peoples, such as Floris White Bull, those arrested and accused of rioting were locked in dog kennel cages without beds, chairs, or furniture. To impose order upon those arrested, Morton County Sheriff Department employees inscribed numbers upon the arms of protestors. The number inscribed on Floris was 151. The scene was dystopic: “I keep telling myself that I’m gonna wake up, because there’s no way I can live in a world where this is possible,” Floris said in an interview.

Source: Oceti Sakowin Camp/Facebook

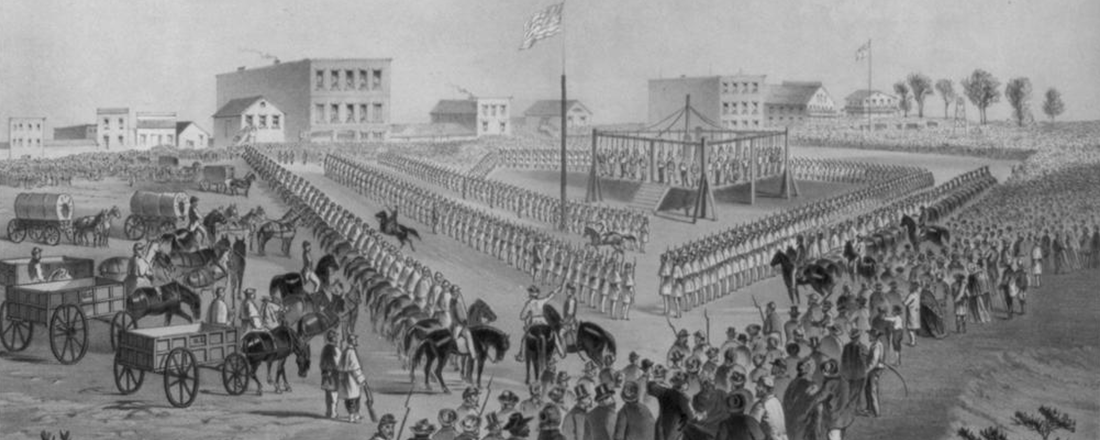

Brutality against indigenous peoples has been systematically used by the U.S. since its creation. Nearly 150 years prior to this particular mass arrest, hundreds of Dakota — relatives of those at Standing Rock — were rounded up and put to trial in military tribunals. Some of these trials lasted less than 5 minutes, were conducted in English, and no lawyers were provided. In total, 303 Dakota were sentenced to death by these military tribunals. President Abraham Lincoln, when presented with the trial records, decided to proceed with only a fraction of the executions. On December 26th, 1862, 38 men and boys were hung to death. This was the largest mass execution in history and the audience — almost entirely white settlers — responded positively to this post-Christmas show.

Execution of the 38 Sioux Indians | Source: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

In both of these situations indigenous people — specifically people of the Oceti Sakowin (The Great Sioux Nation) — were punished for opposing U.S. economic interests. In the historical example, the United States refused to uphold their treaty promise from only a few years prior, in which the U.S. agreed to provide supplies to the Dakota as well as to protect Dakota land from encroachment by settlers. The U.S. government kept neither promise but brutally enforced the portion of the treaty that ceded some land to the government. In the contemporary example, the indigenous people and their allies are opposing a $3.8 billion pipeline which would carry fracked oil from occupied Oceti Sakowin land in North Dakota to outlets for export in the Gulf Coast. The pipeline threatens the Standing Rock Sioux’s treaty rights to water and would pass through unceded treaty land.

Again, in both situations the demand by indigenous people to have their human and treaty rights respected has been viewed by agents of the U.S. as insubordinate and dangerous. In 1862, at Abraham Lincoln’s second annual address to Congress, he said of the “Dakota Uprising” that “the Indian tribes upon our frontiers have during the past year manifested a spirit of insubordination, and at several points have engaged in open hostilities against the white settlements in their vicinity.” On October 27th, 2016, Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier used a similar tactic of centering white victimhood:

“There is a lot of things that are going on, a lot of farmers and ranchers have been stopped, trespassed upon their land. They’re afraid to go places. They have to get their work done, the fall work done. This is very important. That’s why we have throughout this, have increased patrols to make sure everybody is safe. That has been number one from the very beginning. I want everybody in Morton County know that law enforcement is around and that we will respond to their needs.”

– Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier

The wife of Indigenous leader Little Crow and their two children at Fort Snelling prison compound | Source: Minnesota Historical Society/Wikimedia Commons

“Insubordination” and “trespass” are both used in these examples to insinuate that indigenous people have done something vaguely threatening without requiring the burden of proof. However, when it comes time to charge these indigenous people it becomes necessary for government authorities to employ specific and prosecutable terminology.

Riot, riot, riot

On October 14th, McClean County’s State Attorney Ladd Erickson charged non-native journalist Amy Goodman with rioting for filming security staff hired by Dakota Access Pipeline. The incident she filmed, which took place over Labor Day weekend, shows security officers pummeling indigenous peoples and releasing biting dogs into crowds of elders, children, and adults.

Shailene Woodley as she was arrested by police | Source: © LA Times

Just a few days earlier, on October 10th, Shailene Woodley, a non-indigenous actress and ally, was arrested while returning to her RV and was subsequently charged with rioting. October 10th was also a federal government holiday celebrating the progenitor of colonial violence — Christopher Columbus.

“Rioting” has been legally defined as a disturbance of the peace by several persons, assembled and acting with common intent in a violent and turbulent manner. It’s difficult to see how “rioting” would apply to the indigenous people protecting water. While they are a group of several people and they are assembled and they are acting with common intent, their actions have at no point been violent. As of yet, there has not been a single example of a worker, security guard, or law enforcement officer being attacked by the indigenous people gathered at Standing Rock.

Multiple, conflicting chaoses and orders can arise in situations with multiple subjectivities. This is the situation in the Standing Rock camps.

So the applicability of the riot charge to this context hinges on the definitions of “peace” and “turbulent”. “Peace” in this legal usage is not meant to indicate a situation in which conflict is resolved through non-violent means. If that was the intended definition of peace, then a charge of rioting would be more applicable to the law enforcement officers than to Amy Goodman, Shailene Woodley, or any indigenous people at the camps. Non-violent conflict resolution precludes the tear gas, mass arrests, rubber bullets, inhumane captivity, water cannons, concussion grenades, and wrist-breaking employed by law enforcement.

Source: Oceti Sakowin Camp/Facebook

Instead “peace,” in this definition, can only be understood to mean “law and order” — or simply “order”. Conversely, “turbulent” is commonly defined as disorder and invoked through that ancient Greek deity, Chaos. But defining abstract terms with several other abstract terms doesn’t help us understand what has happened and continues to happen to indigenous peoples.

Orders and Chaoses

A cursory look into academic writing reveals an unsettling situation: it appears that the social and critical fields have mostly relinquished the study of chaos to the mathematical and positivist sciences. This objectivist fantasia is referred to as “Chaos Theory” and it takes chaotic systems such as the weather, markets, and my moods as the topic of study. Chaos was famously defined by meteorologist Edward Lorenz as “the present determining the future, but the approximate present not approximately determining the future.” In other words, chaos is not randomness. Chaotic systems have order, but an order which is difficult to discern because any slight variation in the starting parameters will have an outsized effect on the outcome.

“The Chaos” by by G. Nolst Trénite | Source: Busy Teacher

Of course, mathematical modeling is not how the United States government creates or enforces law, so we must turn towards other epistemologies. G. Nolst Trénite wrote a jocular poem entitled “The Chaos,” in which the poet assembles a list of unpredictable english spellings and grammatical constructions. Trénite — a Dutch citizen and non-native English speaker — was equating the unpredictable nature of the English language to the opaqueness of chaos. Of course, “unpredictability” implies a person or subjectivity attempting to make the prediction. Depending on your familiarity with English, the age at which you learned it, and other factors, the language’s idiosyncrasies will be more or less predictable. This poem and “Chaos Theory” point to chaos being a kind of order — albeit one that is difficult to discern based on the vantage point. “Chaos Theory” stipulates that weather is a chaotic system and, therefore, enough data and modeling will reveal the order that governs it, even if from our current vantage point that order is not discernible. In “The Chaos,” English is a grab-bag of arbitrary spellings and constructions or an elegant ordering of sounds, symbols, and meaning depending on your subjectivity.

Thus chaos reveals itself as a personal experience instead of a universal one. Multiple, conflicting chaoses and orders can arise in situations with multiple subjectivities. This is the situation in the Standing Rock camps.

On one side there is a coalition of state agents (politicians, attorneys, and law enforcement), corporations (Energy Transfer Partners and multiple banks), and labor (AFL-CIO). For this coalition, ‘order’ is the North Dakota and United States legal system — as practiced by these agents — and the profit motive. In this view, the situation would be ‘in order’ if Energy Transfer Partners were allowed to proceed unencumbered and, upon completion of the project, pay out profit margins to employees, shareholders, and — through lobbyists and campaign financing — government agents. From this vantage point, the Standing Rock Sioux and their indigenous and non-indigenous allies are the elements of chaos.

On the other side is a coalition of the Standing Rock Sioux, other indigenous peoples, and non-indigenous allies, predominantly environmentalists. Their ‘order’ is and has always been the natural order of a sacred relationship between man and nature, motivated not by profit but by respect. Once the respect is gone, then the end of the world is upon us.

Apocalypses Up Till Now

An apocalypse is a moment of maximum chaos when an established, relatively predictable order is replaced with an unpredictable order.

The Lady of Cofitachequi showing Hernando de Soto her ‘treasure’ | Source: © Native History Association

In 1540, Hernando de Soto leveled his firearm at the head of the Lady of Cofitachequi, the person in charge of the indigenous people who would eventually become my tribe, the Catawba Indian Nation. De Soto was angry because after several weeks of hospitality, he and his men were being evicted. In retaliation, he kidnapped the village’s leader and demanded that she take him to gold. Being the intelligent indigenous person that she was, the Lady of Cofitachequi led de Soto deep into the Appalachian Mountains. Early one morning, under the cover of the thick fog that these mountains are known for, she ran away from de Soto and his men.

Thus began the 476 year (in our calendar) Catawba apocalypse. By the beginning of said apocalypse in 1540, the Taíno people in what is now called Haiti had already been dealing with their own apocalypse for 48 years. Indigenous communities around the world have stories and start-dates for their own apocalypses, usually coinciding with the invasion of European colonizers.

An apocalypse is a moment of maximum chaos when an established, relatively predictable order is replaced with an unpredictable order. While Western storytellers often imagine that the apocalypse comes about naturally or by accident — such as an apocalyptic natural disaster or a zombie apocalypse — indigenous apocalypses were precipitated by colonialism. From the #StandingRockSyllabus, “colonization destroys in order to replace.” Colonization is an apocalypse.

From this historical perspective, the violent action of government agents at Standing Rock in the name of corporate profit is only the latest episode in a centuries-long apocalypse. It can be seen that these actions seek to destroy a millenia-long ecological and spiritual order with a pro-corporate capitalist order. From this perspective, Dakota Access Pipeline is a chaos.

Source: John Duffy/Flickr (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Of course, indigenous communities knew about apocalyptic natural disasters. Pacific Islanders, Inuit and Iñupiat people of the Arctic Circle, indigenous people of the Amazon, and the Standing Rock Sioux themselves warn of the imminent apocalypses that await us individually and collectively through time and space. Indigenous people now, in the past, and likely into the future, warn that the replacement of a reciprocal, relational ecologic with an insatiable profit logic will end in disaster and already has.

Dealing with Chaos

Chaos reveals itself as a personal experience.

On November 20th, hundreds of water protectors were attacked with a water cannon in sub-freezing night temperatures, rubber bullets, and tear gas. One youth suffered a grand mal seizure, an elder required emergency CPR after having a cardiac episode, and numerous people were diagnosed with hypothermia. One woman was hit with a concussion grenade, has undergone multiple surgeries, and will require hospitalization until it is determined if she will require amputation of her arm (here’s a GoFund link to help donate and cover her bills). This is how Energy Transfer Partners, Morton County, North Dakota, and the United States government deals with the perceived chaos of praying water protectors.

Source: Oceti Sakowin Camp/Facebook

Source: Oceti Sakowin Camp/Facebook

This stands in direct contrast to how indigenous peoples have dealt with the violence of centuries-long apocalypse: focusing on survival, continuity, community, and the maintenance of sacred and ecological relationships with the earth. Humans stand on the precipice of unprecedented global chaos and we must follow the leadership and knowledge of the Standing Rock Sioux and other indigenous peoples, instead of the leadership of the government officials who have brought upon this local chaos before us in the first place.