ANTHONY P. REALE

The cast photos for The Wiz Live! are somewhat mesmerizing. My favorite one features Amber Riley, Uzo Aduba, and Mary J. Blige (Addapearle, Glinda, and Evillene respectively) standing in characteristic poses: Ms. Riley is a picture of utopian, Oz-esque wonder, Ms. Aduba gazes benevolently towards the viewer, and Ms. Blige looks maliciously up and to the right, a vision of the overreaching usurper who is poised to take the throne by any means necessary. These expressions, alongside each of the women’s beautifully intricate costumes, paint an image belonging to a world of psychological depth, where these three women are potentially at war with each other — leading me to believe that I will fall into their world by watching them, wandering Alice-like through the world in which they coexist.

Amber Riley, Uzo Aduba, and Mary J. Blige as Addepearle, Glinda, and Evillene respectively, from The Wiz Live! | Source: © Paul Gilmore/NBC

Unfortunately, this photo (along with any photo from any of the ilk of NBC and Fox’s Live! era) is misleading. They point to this deep and entirely viewer-imagined world, as if these stills capture the spirit of the show that they reference. These musicals have a single stage, but their singular nature is their undoing: the sets fall flat. Regardless of their good intentions, the feeling that these productions take place in a dilapidated airplane hangar cannot be shaken.

Take Peter Pan Live! for instance. Peter, played by the energetic Allison Williams, leads the Darling children on the canonical and mysteriously short flight from London to Neverland during the song “I’m Flying.” This flight, allowed by the sudden revelation that the Darling children’s bedroom wall can split open when they find it most convenient, features a sequence where the group flies over a quaint, one-eighth model of the city. The buildings, too close to the actors, give the hellish impression that giant children can take flight at any time in this bizarre alternate London. The whole flight isn’t as nightmarish, but it does feature Williams unceremoniously adjusting her microphone and the poorly executed laser projection version of Tinkerbell twitching and jerking as she leads the way against the nearest wall. As we reach Neverland, there’s a long cut of the children “looking” at the fantastical place, yelling things like “Gorgeous!” and “Beautiful!” Meanwhile the audience begins checking their watches to see how long this (frankly) beige sequence has taken.

What I find so challenging about watching this scene is the sheer lack of visual machinery. The flight loses its charm before the Darlings and Peter have actually left the bedroom, mostly because the walls fly open solely for necessity rather than climactically. Seeing the mechanics of a sequence is something that makes or breaks a show for me, so the fact that the flight lines are nearly imperceptible is not a feat of technical success to me; it’s a distraction. One review calls it so bad that it’s good, but I take it more as antiseptic. Part of what I find so excellent about theatre is seeing the machinations: if I can forget that I’m seeing an actor’s flight lines, that serves as a confirmation that the show is mesmerizing enough to block out the real-world technologies that make the illusion.

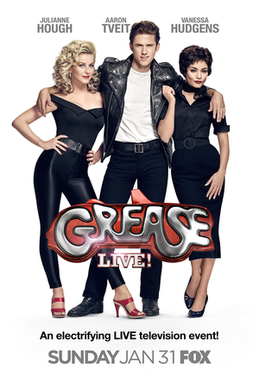

Peter Pan Live! isn’t the only perpetrator of this sensation of claustrophobic and clinical precision; choose any of the other Live! shows. Grease Live! features the lighting and scenery of a rundown suburb. Jesus Christ Superstar: Live in Concert goes for an ancient look, complete with metal scaffolding one might spot in present-day downtown Los Angeles, then blocks the scenery from being seen in its elaborately-lit and fog-filled song sequences. Even The Wiz Live! (my personal favorite and, I believe, the best, most successful, and talent-heavy member of the Live! family) dazzles its audience into a stupor with the use of floor-to-ceiling LED screens.

‘Jesus Christ Superstar Live in Concert’ First Look | Source: © hollywoodstreams/YouTube

Regardless of their good intentions, the feeling that these productions take place in a dilapidated airplane hangar cannot be shaken.

I didn’t write this article to just angrily denounce these iterations of the musicals that you and I grew up loving. I in no way mean to detract from the talented people who have worked on these pieces. I’m not a critic of the content as much as I’m a critic of the medium. There wasn’t ever a need for the performing arts to head in this direction. Theatre was never meant to be made for television. If that were the case, theatre would have died the minute the first television clicked on.

Grease Live! | Source: Wikipedia

This fad of Live! musicals follows a trend of what is a special version of planned obsolescence. Instead of the common version that might be coming to your mind — ahem, Apple iPhone batteries, ahem — I’m thinking of a more fashionable obsolescence, something that makes people lease cars instead of buying them or have closets full of clothes they’ll wear once. Not many of us are exempt from this; I bet you can imagine a car commercial in precise detail. I know this seems off-topic, but bear with me. You know what I’m talking about. There’s sweeping turns, a quiet narrator who tells you about how your life will be massively improved by leasing the vehicle, and idyllic scenes of long drives. These are the perfect tools to make you jealous of who you could be. (There’s an excellent episode of a podcast called Throughline about it; I highly suggest it. It’s call “The Phoebus Cartel.”) This fashionable obsolescence fuels our buying power. We, whether subconsciously or not, are obsessed with being on trend.

This glaringly transparent consumer pitfall extends to most industries merely because we are predisposed to groupthink and something I call the “Ooh! Shiny!” Complex. Unfortunately, theatre is not exempt. We see the newest stage technique and instantly contort it to fit the piece that we’re running on the mainstage (sorry Chekhov, realism is so 1880’s). This happened with projections and LED screens most recently, if you’re looking for an example.

Justice to the story itself should be the crucial aspect of the performing arts, or (more glibly) just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

In my search to understand more about these television musicals, I did some research about the executive production team that was behind NBC’s arguably groundbreaking breach of the musical world for television filmed in a warehouse. I found Craig Zadan and Neil Meron, two men who have had a storied history in executive production. They have won the following awards: six Academy Awards, five Golden Globes, 22 Emmy Awards, two Peabody Awards, a Grammy Award, six GLAAD Awards, a Critics’ Choice Award, four NAACP Image Awards, and two Tony Awards. Suffice to say, their work is good. These two people have produced some personal favorites of mine: both the 1984 and 2011 Footloose movies, 2007’s Hairspray, the Cinderella that featured Whitney Houston, and Chicago (which won an Academy Award). Zadan and Meron have had a hand in revolutionizing the way stories are told and have been recognized as forces. But their hunger to induce an unnecessary evolution of live theatre’s medium further disconnects from the end goal of live performance; perhaps their success with Chicago brought them to the clouded conclusion that they might be impervious to the pitfalls of fashionable obsolescence.

Theatre was never meant to be made for television. If that were the case, theatre would have died the minute the first television clicked on.

Live performance proves to be something sacred and unnatural; when someone is performing on a stage, they can see the audience’s eyes tracking their movements. Any shocking line is to be greeted by a gasp; any comedic line should garner laughter. It’s an interaction underscored by the silent contract that the audience listens and watches while the performer is seen and heard. When something is broadcast live, the unnatural element is amplified. Instead of a number of recognizably human eyes, one uncanny glass eye stares, not offering anything to the actor (who functions as a receptacle as much as they are a provider). Sure, television and movie actors can have some reliance on the idea that they’re humorous, but the absence of a real audience lacks the confirmation that actual laughter brings.

Grease Live – You’re the One That I Want | Source: Applejack Becca/YouTube

I don’t mean to disregard the work of screen actors. However, I think there’s a fine line between revolutionizing the medium and losing the clarity of the form. As you introduce the uncanny glass eye into the realm of theatre, you begin to lose control of the sacred connection between audience and actor. In the darkened, quiet room, an actor can tell if someone’s talking over them; the screen actor is not afforded the same ability — that is to say, a screen actor’s impassioned soliloquy might be ignored wholeheartedly in a manner comparable to the neglect jazz receives at dinner parties.

Storytelling should evolve, yes. If it didn’t we’d still be looking at plays performed in front of a Greek skene. I’m not suggesting that we should all be Luddites who bury our heads in the sand; there’s a reason why we progressed past the gas lamps of the age of melodrama. But being a mindless trend follower in storytelling is what happens with the Live! family of musicals. Most press releases regarding these shows talk about how the show uses the most modern technology and draws the most viewers, but theatre shouldn’t be about beating the competition. Rushing into some novel medium of storytelling without considering the fact that the story might not need to be told that way is detrimental to the story itself.

Justice to the story itself should be the crucial aspect of the performing arts, or (more glibly) just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. What is suited for puppetry is not necessarily suited for three seasons of a television show. I had a teacher once say to me, “hold on tightly, let go lightly,” which seems a prudent quote to share in this case; if the medium serves the content, pass Go and collect $200. But to move forward without this consideration is disrespectful — and I’d go as far as saying damaging — to theatre itself.

The Wiz: Live! – Trailer | Source: © YouTube Movies/YouTube

As I watch The Wiz Live!, wondering about why these Live! musicals happened, the citizens of Oz welcome their intrepid visitors to their verdant city. They pose, covered in the garb from the futuristic city of some child’s daydreams, as they talk about the damage that their great and powerful leader can inflict. Their voguing forgets the roots of this greeting; in the 1978, Donna Summer-led version, the citizens of Oz sing about the colors they wouldn’t be caught dead wearing. In that 1978 version, the population shifts their mindsets with an absurd, whiplash-inducing speed at the beck and call of their trendsetting demagogue of a leader. Within three stanzas, the amorphous spiral of lolling, chic citizens have swiftly and deftly established “how quickly fashion goes down the drain.” As this film version shows us, fashion and planned obsolescence are inextricably linked. Trends will be arbitrarily set and followed mindlessly. Green will be replaced by red, which will be replaced by gold. How can one keep up with the vacillations of a fatuous leader without falling behind the trend into social ineptitude? Citizens of Oz, I hope you’re questioning this process; the man behind the curtain may be deceiving you. If we’re all judging each other and thoughtlessly marching towards the next trend, he can get away with whatever he wants.