SWEDIAN LIE

We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.

– H. P. Lovecraft

In 2014, British artist Anish Kapoor shocked the art world when he acquired exclusive rights to the artistic use of the “world’s blackest black” material, Vantablack, effectively preventing anyone — artist or otherwise — from using the material. Created by British nanotechnology company Surrey NanoSystems, Vantablack is neither a paint nor a pigment, but rather a coating of carbon nanotubes, what Surrey NanoSystems called a “functionalised ‘forest’ of millions upon millions of incredibly small tubes made of carbon.” These carbon nanotubes absorb more than 99% of the light that hits the coated surface, essentially trapping the light particles within incredibly tiny gaps between the nanotubes and preventing them from being reflected back out.

The physical phenomenon of light bouncing off of surfaces is at the heart of what we call “color,” which is more like a complicated, interpretive sensorial experience than a tangible object. Color is the result of our brain and eyes making sense of the wavelengths of light bouncing off of and interacting with physical objects in the three-dimensional world. In the case of superblack substances like Vantablack, where no light is being reflected back into our eyes, we see the coated object as an entirely flat emptiness — a complete incongruity to everything else we perceive visually. First produced in collaboration with the British government and other technology companies precisely for this incredible abyss-like feature as its “ultra-low reflectance improves the sensitivity of terrestrial, space and air-borne instrumentation.” All this is to say, Vantablack is not and was never meant to be used as a commercial art product, sold in art stores alongside tubes of oil and acrylic paints. It was designed to blend into the nothingness of outer space.

VANTABLACK – The Darkest Material on Earth | Source: © Wonder World/YouTube

So why was Kapoor interested in something that, as Surrey NanoSystems themselves revealed, is “not available to private individuals”?

To answer this question, we first need to understand the power of black as a color — a color “so emotive” that it has a “psycho side” to it, according to Kapoor. What it is about black that we find so compelling?

The Substance

Venture inside the iconic Lascaux Cave in southwestern France and you’ll see cave paintings nearly 20,000 years old, each depicting life during the Paleolithic era. You’ll see horses and bulls and human figures rendered in striking and articulate brushstrokes, with vibrant reds and browns defined by bold blacks. This is no mere documentation, but one of the earliest examples of creative expression — something we today might call “art.”

A number of cave #paintings from Lascaux #France discovered on this day in 1940 https://t.co/RaG1yTDZT0 #cave #art pic.twitter.com/F8EwhpI3as

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) September 12, 2016

Source: © Bradshaw Foundation/Twitter

The ancient Paleolithic artist was confined in their choice of materials to the byproducts of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the time. Hence, many reds and browns were produced by various minerals and iron-rich soil (the same iron that gives our blood its reddish hue), while black was created by burning all kinds of organic materials, including grape vines and willow sticks, to produce charcoal. From its earliest use, black has always been an essential color and material in storytelling — its very process of creation containing moments of production and destruction. Where one story ends, another begins.

Black as a substance used in art […] holds within it the potent story of transformations and transitions; moments that often require pain, suffering, and destruction in order to create new life or a new expression— not unlike the story of human civilization itself.

Although it is difficult to know for certain, it seems that in these early days of art, its practice was associated with sacred, divine, and symbolic meanings. In certain indigenous cultures for example, charcoal was used in ancient rites of passage in order to create physical marks (temporary and/or permanent) that symbolized the transformation of the individual into their next phase of life. In Papua New Guinea, adolescent women of the Korafe tribe have designs drawn with charcoal on their faces in preparation for one of the most extreme coming-of-age rituals in human history: facial tattooing. In Ethiopia, teenage men of the Hamar and Karo tribes are ritualistically smeared with a mix of charcoal and butterfat before they undergo the manhood ceremony of bull-jumping. As these examples illustrate, the color black holds particular significance in moments of transition, whether from childhood to adulthood, or the human realm to the heavens.

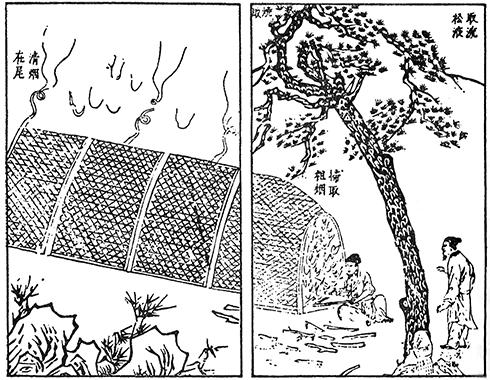

15th-century drawing from China detailing the process of burning pine wood to acquire soot for inkmaking | Source: Song Yingxing/Wikipedia

In ancient China, the color black manifests mainly in the form of ink, created either by mixing natural plant dyes with minerals such as graphite or by burning pine wood to produce soot and mixing it with water. Inksticks were made by combining the ink with animal glue, which renders it into a solid state that can be dissolved when the stick is given water and ground against a hard stone — an act that is both a physical gesture of labor as well as a symbolic gesture of effort and perseverance. On the other side of the world, ink was produced in various parts of Europe through the harvesting of oak apples — which aren’t apples at all, but tumorous parasitic growths (also known as galls), caused by the larvae of gall wasps. Centuries down the line, Renaissance artists would stock their painting arsenal with “bone black” (also known as “ivory black” or “bone char”), a black substance created by burning animal bones in an air-free environment, so that any and all impurities — which might produce non-black colors — are removed.

Wild Plant Ink: Making medieval ink from oak galls | Source: The Foragers/YouTube

In these examples and others across time, black as a substance used in art (in its ever mutating understanding throughout human history) holds within it the potent story of transformations and transitions; moments that often require pain, suffering, and destruction in order to create new life or a new expression— not unlike the story of human civilization itself. It is not surprising, then, that most people interpret black as the symbol and color of death, evil, and fear — all negative connotations associated with the human life cycle. Even in the modern era, black has always been viewed as something incredibly austere, severe, and harsh — a foreboding presence that sucks all life out of the things around it. This is certainly how many Abstract Expressionists viewed and used black in their work, in part also influenced by the dramatic realities of the world wars around them.

The color black holds particular significance in moments of transition, whether from childhood to adulthood, or the human realm to the heavens.

Yet black has so much more potential as a color than just to simply represent the bleakness of life. In traditional Chinese calligraphy and art, artists frequently use black and its various shades of gray to depict incredibly detailed and vibrant scenes of life. In their understanding, black is the color of purity and humility — austere, yes, but also sincere and true. During the Song dynasty, Chinese ink wash painting was considered — alongside calligraphy — as the highest form of art, performed by the most gifted scholars and intellectuals, and arguably the earliest examples of landscape painting was born out of this period. The 7th-century artist Wu Daozi was considered as one of the best artists of this period for his sole use of blank ink to meticulously render human figures in incredible detail.

An unnamed work by Wu Daozi | Source: Source: Le Confident

Artists like the 20th-century Qi Baishi, one of the greatest modern traditional Chinese artists, continue this tradition of using black ink. For Baishi, only black can tell the story of Chinese life while inviting the viewer to meditate on traditional principles, morals and norms, without having the other meaning-laden, emotional colors prejudicing or distracting the viewer. Of course, artists do use and have always used non-black colors to great emotional affect, but black as a color has the unique ability to simultaneously define the image for the viewer, as well as disappear out of the viewer’s consciousness, thereby allowing the viewer the space to find meaning — whether the fragility of life or its abundant potential — within the artwork.

The Absence

If black is one of the earliest colors in the painterly arts, black as a color in the theatrical arts is a comparatively newer concept — mainly because black hasn’t always been understood as an element even capable of storytelling in the performative sense. For one, black was first understood in the context of physical performance — that is, a temporal activity happening within a specified space — as an absence rather than a substance. Black has been understood as the absence of light.

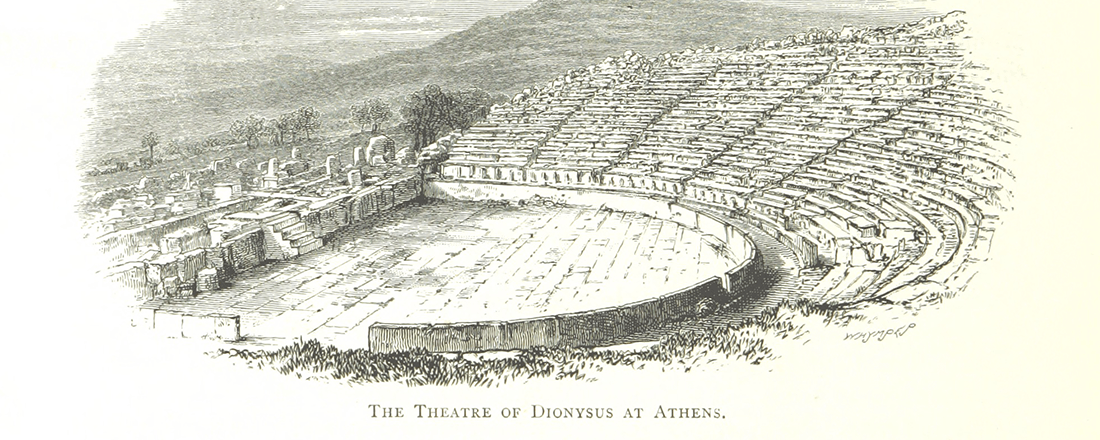

Source: The British Library/Flickr

In the open-air tradition of ancient Greek theatre, performances were held during the day when there is ample sunlight, and any night scenes were explained or described as such by the chorus. Black in theatre meant darkness, and darkness meant either the end or the beginning of a show — never the action itself. In this way, black came to be associated with nothingness — yet, there are an infinite number of possibilities in nothingness. When theatre moved indoors and performances were lit by torches and candlelight, there now existed spaces within the playing area that are dark and unlit, but still available to play in. Theatre artists can now begin to think about darkness and its black color as a shape and performer, malleable to their artistic intentions and goals.

Consider the humble black theatre curtain. We know that in the Elizabethan era of Shakespeare, black drapes and curtains were used to define both time and space — to start a performance (by the opening of the curtains) as well as to demarcate the boundaries of the stage itself. The 1599 anonymous play A Warning for Faire Women has the following lines to describe the typical Elizabethan stage experience:

The stage is hung with black: and I perceive

The auditors prepared for tragedy.

From here we can determine that the use of black soft goods as a physical presence in the space was meant to communicate certain messages to the audience. It can be as simple and straightforward as ‘the play is starting,’ but it can also be as symbolic as ‘this story is as somber as a black mourner’s robe.’ In this sense, then, black has become a color on stage — a substance rather than an absence, now able to carry meaning for the audience members.

19th-century woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi of kabuki actor Nakamura Shikan II and the three kuroko accompanying him | Source: Utagawa Kuniyoshi/Wikimedia Commons

In certain performance cultures, the color black is also personified in human figures who move through the playing space. Although the viewer is meant to ignore their presence, the use of black-clad stagehands is an ancient practice, and in the Japanese tradition of kabuki theatre, the stagehand known as kuroko is unique for their function and look: dressed in black from head to toe and often wearing a mask as well, these stagehands perform the role of the run crew onstage by moving pieces of scenery, bringing on and off props, and even assisting in costume changes, all within full sight of the audience. The all-black attire is meant to tell the audience that the kuroko is not part of the story and do not have a significant role in the performance — even though, without them, the performance would not be able to unfold as fluently. Interestingly enough, the highly stylized kabuki stage often features a beautifully painted backdrop as part of the set design, so the kuroko may not disappear as easily as they would in, say, a deep, dark proscenium stage.

Modern entertainment programs in Japan have begun to play and subvert the idea of the kuroko, fully acknowledging their all-black presence, often to great comic effect. The best example of this is the popular variety show Masquerade (known in Japan as Kasou Taishou), which pits groups of amateur performers against one another in coming up with the funniest and most entertaining skits, often involving the humorous use of kuroko. Black no longer has to be somber or severe — black can be side-splittingly silly as well.

Karate Master/驚異的空手道館 (from Masquerade) | Source: masqueradentv/YouTube

In the West, this malleability of black in the theatrical space has resulted in the emergence and development of “black box theatre,” a genre of theatre that often takes place inside something akin to a standard rehearsal room — the eponymous black box — and is usually experimental in nature. By getting rid of the traditional proscenium and its accoutrements, black box theatre has also gotten rid of traditional understandings of black in the physical space and opened up an entirely new world of performative possibilities.

I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space, whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.

– Peter Brook

These words by theatre director and scholar Peter Brook in his seminal The Empty Space exemplified the principles of black box theatre — that in the blank space of the black box, there is an untold number of stories and narratives all waiting to unfold. The space does not place limitations on the narratives it can convey. From here, one can go anywhere with a performative idea — literally, as in the case of site-specific theatre pieces such as Punchdrunk’s famous Sleep No More, or site-agnostic theatre pieces such as Nassim Soleimanpour’s Red Rabbit White Rabbit or Tania El Khoury’s theatre-for-one experience As Far As My Fingertips Take Me. Where once upon a time black meant the show was no more, nowadays black is wherever the story brings itself to life.

The Void

Now that we have begun to understand black’s value as a color, we can also begin to understand Kapoor’s interest in something like Vantablack. Kapoor is most famously known for his monolithic sculptures, most of which investigate our relationship to and processes of spatial perception through a variety of earthly materials. Some of his most famous works include the iconic Cloud Gate in Chicago — better known as the Bean — and his Void series. Each of his works thinks about space through either substance or absence, and in the case of the Void pieces, Kapoor was particularly interested in turning the visual perception of flatness — that is, the lack of dimensionality — into a dimensional object in itself. Vantablack could be a watershed breakthrough into this approach.

Perhaps the darkest black is the black we carry within ourselves […] It’s not the night where you switch the lights off — it’s the night where you close your eyes.

– Anish Kapoor

The MCT S110 Evo Vantablack | Source: © MANUFACTURE CONTEMPORAINE DU TEMPS

Understandably, many artists have denounced Kapoor for what they call his selfish desire to monopolize the use of a color — even though Surrey NanoSystems have gone to great lengths to say that Kapoor’s license is only for the commercially unavailable Vantablack and not black as a color in itself. Artists such as Stuart Semple have responded by producing their own ‘blackest black’ material, and similarly NanoLab, a nanotechnology company based in the U.S., have released their own product — Singularity Black — and made it available to the public. Ironically, ever since Kapoor acquired the license to Vantablack, he has created very few public works out of it, one of which being the 10-piece limited edition MCT S110 Evo Vantablack, a $95,000 luxury watch that uses Vantablack on some of its components — hardly an accessible piece of art.

Ultimately, this years-long controversy around Kapoor and Vantablack boils down to a matter of principle: given all that a color means, to humanity and to society, can it be owned? Is color a physical, tangible object that can be patented, copyrighted, and used for capitalistic purposes? Or, is the philosophical journey of meaning and narrative, traced in this piece. innate in color’s ability to communicate?

Can You Own a Color? | Source: © PBS Idea Channel/YouTube

The most interesting invocations of black have been those that reflect origin stories; chronicling humankind and society, from the hunter-gatherer past into an imaginative future. In becoming the sole artistic licensor of Vantablack, Kapoor may have obtained the blackest of black materials and the seemingly “perfect” conduit for his artistic endeavors, but he has also introduced a device that cannot reflect life back onto his viewer — no story, no character, no meaning, no color — a flat black void of emptiness that was never meant to tell stories, but simply exists in the cold darkness of space. Kapoor stands alone in this black copyrighted island of his, an island of ignorance to the true infinite possibilities of ‘the color of no color.’