KYLÉ PIENAAR

In March 2015, students at the University of Cape Town (UCT) demanded the removal of the Cecil John Rhodes statue that had been a focal point on campus for over 80 years. The protest action grew, building to a movement called #RhodesMustFall. After a lengthy occupation of administrative buildings on campus, Rhodes fell. By then the goals of student activists had broadened, and movements swept campuses across the country: #FeesMustFall; #OutSourcingMustFall; #PatriarchyMustFall.

#RhodesMustFall Protest | Source: milimalde/Twitter

‘Fallism’ takes institutional racism as its core concern, along with the attendant economic inequality that locks poor students out of universities. As the large bronze simulacrum of the infamous colonist was removed from his perch, student activists set their sights on decolonized education.

Ameera Conrad was a student at UCT during the protests. She performed in and co-curated The Fall, a workshopped play about the student movements.

Many people who saw The Fall were likely seeing the story told by students for the first time, as opposed to what they were able to cobble together from the news media.

What sort of impact does storytelling have on your work, and how do you see your own storytelling effecting change?

Ameera Conrad

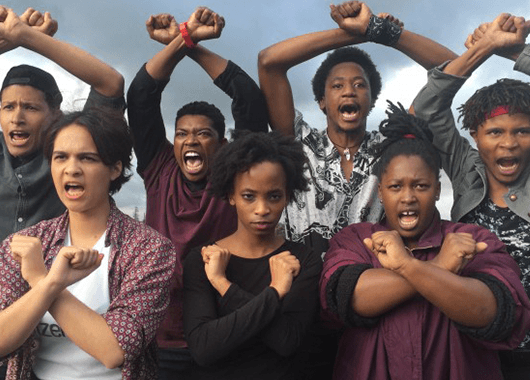

Source: Phaks/Twitter

I think as a theatremaker that storytelling is really the root of my approach — at the end of the day regardless of whether or not your characters break the fourth wall and talk to the audience, you’re always telling a story in theatre. Whether it’s fictional or not, whether it comes from personal experience or not, the heart of the theatre is a story needing to be told. Otherwise, we wouldn’t really make it. And I think that for The Fall in particular, the storytelling aspect was very important; in fact it was the reason that we were initially approached to make the play. The Baxter [Theatre Centre, a theater company in Cape Town, South Africa] was so interested in hearing our voices that they asked us to just tell our own truths.

Obviously, we don’t claim to be the be-all-and-end-all of the student protest narrative, we’re very aware — and I think the play makes it clear — that there are so many kinds of voices and opinions and perspectives to consider, that we can’t be seen as the only narrative. But it’s so important to start with the many voices, if that makes sense, because if all of the characters have the same voice, then the story has no fire or internal drama. Then we might as well just read the news.

The Fall promotional photo | Source: © The Baxter

I think the biggest impact that The Fall has had — apart from giving space to young of colour performers and theatremakers — was to give the audience members who weren’t in the movements a taste of what it was like to be us, to feel what we felt in the moments of elation and of fear. And that made people think about the movements in new ways and consider the students as what they are: just people trying to do something meaningful.

When you think of the history of South African theatre, the big names are people like John Kani, Athol Fugard, Mbongeni Ngema, and Barney Simon (to only name a few). And we know them, largely, as practitioners of protest theatre — writing and performing against Apartheid.

How do you see your work fitting into that genealogy, and grappling with that inheritance? Do you consider what you do as protesting against something? Are you trying to build something new?

Ameera Conrad

I think it’s a matter of standing on the shoulders of giants. The whole cast was at UCT’s drama department together, so we were all taught the great South African protest texts. We were taught by the people who performed in those texts in the 1980s and 1990s, who worked directly with the people who you mentioned, and still do. So I think that we were always so aware of what the legacy was that we were, as you say, inheriting.

As a group of actors and theatremakers who were involved in the protests, I think we realized quite early on where our major contribution to the [student] movements could be — and that’s in archiving through art. For The Fall, there’s definitely a clear sense of taking the form of a Barney Simon-esque docu-drama and using a contemporary story for that form. We were very clear that that was our idea. [So] I definitely think that we’re using what has come before us and updating it for the now. The Fall uses projections of video footage from Facebook — which we thought was a very clever way to show how our generation documents things.

I personally don’t consider it to be a need to build something completely new; more like a renovation, you know? Changing the linoleum floors here and there, putting in some fancier appliances, under-floor heating, adding a movie theatre in the basement; that kind of thing.

Related to this, The Fall was a workshopped piece. Workshopping has such a long and illustrious history in South African theatre. What was that experience like?

Ameera Conrad

It was exhausting. And I think everyone in the cast would agree with me that by the end of the run we were completely knackered — but also invigorated by the idea that we had made this, and we had made this together.

The Fall | Source: © Oscar Oryan/Times Higher Education

The movements have a concept of horizontal leadership — effectively, [that] there is no leadership [and] we are all responsible for ourselves and for each other — which was something that we wanted to emulate. [In the play] Thando Mangcu and I were the cast curators, because we had graduated with a degree in theatremaking, so we had the experience to help the group refine ideas and choices. And we were, of course, facilitated by the incredible Clare Stopford, who served as an outside eye and was such a huge help to us as actors in reminding us why we were doing what we were doing and to pose questions to us as someone from the outside. We worked incredibly well together, and after many drafts of the play —some of which were horrible — we eventually came to the piece that we have now. We fought a lot, challenged each others’ ideas, [and] did a lot of learning and unlearning.

People have this perception that if you workshop a play you have to compromise on quality — and that was something that we didn’t want to do. So even now, as we’re preparing for our 2017 tours and runs, we’re thinking of where the show can be improved, which lines didn’t get the response that we’d hoped for, and which moments need to last longer or shorter — and the beauty of having workshopped it is that we can make those changes without consulting the writers, because we are the writers!

What do terms like “born-free,” “new South Africa,” and “Rainbow Nation” mean to you? They were such formative parts of my own youth, and the mythology I grew up with of “Post-Apartheid South Africa.” It’s been amazing to me to watch Fallism blossom and complicate these very simplistic narratives of nation building.

Do you see your work as engaged with that?

Ameera Conrad

I think “Rainbow Nation” is actually the perfect way to describe South Africa — so many colours that are completely separated from one another except on the edges. I was always told that I was a “born-free” — even though I was born in 1993 [and the phrase is usually applied to those born after the end of Apartheid in 1994] — and I never really understood what that meant.

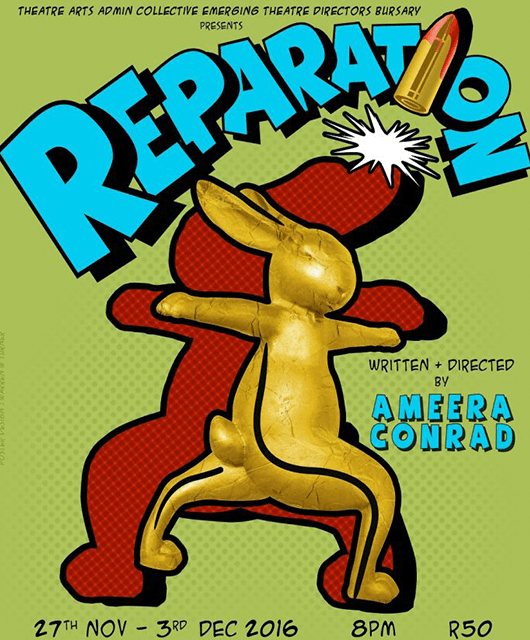

Reparation | Source: MyPR

I think, growing up, the assumption is that my generation is free of the difficulties that the generation before us had to deal with, so our lives are suddenly easier — but that’s clearly not the case. I did a Q&A after one performance of Reparation [Conrad’s play after The Fall] where I said that the generation before us had a clear enemy; everyone knew that the Apartheid government was the problem, [and] it was clear to the entire world. Our generation, on the other hand, have so many enemies from so many sides that it’s difficult to unite against them, because some of our enemies are also our friends — and they don’t mean to be our enemies, they just happen to be [so] because history has made them that. I think that my work is definitely trying to grapple with all of those things, in the same way, that I’m trying to grapple with it personally. It always ends up being my own way of trying to figure things out.

Reparation became a scathing look at the way the post-1994 government has built a nation on the notion of non-racialism, and yet we are expected to exist among blatant racists. I’m still amazed at how people like Wouter Basson and Eugene de Kock are able to walk among us like nothing happened when they committed gross crimes against humanity — although I suppose they don’t see people of colour as human, so maybe that’s the logic.

Are there shared stories South Africans tell themselves that you see as dishonest, or reductive? Are there national myths you want to explode with your work?

Ameera Conrad

That we’re all equal. That’s the line that makes my blood boil — when someone who has had an entire world of opportunities opened to them, whose parents were able to provide limitless experiences for them, and who made their lives so much less stressful tell me that “white privilege isn’t real” and “we’re all equal” when the system entrenched in our country — the architecture of our country; the education system of our country — all prove that we’re far from it. All of the work that I make, or that I want to make in future, stem from that, I think. We’re not equal, and the only way to actually become equal is to admit that we’re not and then actively work towards fixing the problem.

Planning the settling of black South Africans into ‘native townships’ | Source: © Apartheid Museum/The Guardian

I’d also like to tackle, at some point — and we start doing it in The Fall, but I’d like to explore it further — the coloured narrative, which I think has been reduced to gangsters shooting up the Cape Flats, or smiling singing performers in District 6. And I think being coloured is so much more interesting than that; so much more layered and dynamic and complicated.

I read Reparation described somewhere as a “no-holds-barred examination of post-Apartheid-Apartheid South Africa.”

I’m interested in what the phrase “post-Apartheid-Apartheid South Africa” means to you.

Ameera Conrad

I wanted to make it very clear that Reparation was not going to be polite, and this phrase “post-Apartheid-Apartheid South Africa” had been floating around on my social media and I wanted to engage with it. For me it’s about looking very seriously at the changes that were made post-Apartheid, and accepting that just because the governmental regime has changed, does not mean that the problems have disappeared.

A township in Soweto, Johannesburg | Source: Wikimedia Commons

People of colour — who make up the overwhelming majority of the impoverished and lower-income households — are still relegated to the fringes of the city. Architecturally we still have monuments to men who were instrumental in the systemic oppression of these people. We still view the Western ideologies of ‘modernity’ as that which we should aspire to, completely disregarding hundreds of years of traditional practices and schools of thought. Majority black and coloured schools and universities are still lacking in infrastructure, and we still have townships. These things have become so normalized in our society because we see the country as better than it used to be, but just because it’s better than it used to be doesn’t mean we should just accept it and not try to actually make this country the best it can possibly become. For everyone — not just the rich white people.

Who are the storytellers in South Africa today that you looked to and admire?

Ameera Conrad

Koleka Putuma | Source: © The Daily Vox

There are genuinely so many that it’s going to seem like one long list, but here we go: Nadia Davids, Quanita Adams, Amy Jephta, Koleka Putuma, Nwabisa Plaatjie, the entire Age of Artists group, the entire Hungry Minds Productions group, Lara Foot, Clare Stopford, Philip Rademeyer, Jaco Bouwer, Christian Olwagen, Jay Pather, Mark Fleishman, Jason Jacobs, Genna Gardini; there are a lot more, but my brain has stopped producing names for a bit.

I’ve been very lucky to have been able to work with almost all of these names in some capacity — as an actress, writer, director, or stage manager — except for Jaco Bouwer, but I’ve got so much time to tick that off my list!

What’s next for you? What are you working on now? What do you hope to accomplish in the years ahead?

Ameera Conrad

I’m about to start work stage managing for Philip Rademeyer’s new production of [novel] Monsieur Ibrahim en die Blomme van die Koran, starring [South African actor] Dawid Minnar, which will tour to [theater festivals] KKNK and Suidoosterfees. I’m excited and nervous to work on an Afrikaans production, as I’ve not done that in a while. We’re also starting our preparation for The Fall’s tour to Stellenbosch for [theater festival] Woordfees. I’m also currently working on a few script concepts and writing that I’m very excited about bringing into fruition in 2017 and 2018.

In the next few years, I’d like to have been able to produce a few new productions, either as a writer or as a director. I’ve got a few tricks up my sleeve and a few collaborations on the horizon which I’m very excited about.

What is the future of South African theatre? What are young people like you concerned with? What sort of forms and experimentation are exciting you?

Ameera Conrad

I’m excited that young people are going to the theater again. I was recently in a discussion where a gentleman said that the millennials made it difficult to make money in the theatre these days because we’re so obsessed with social media and Netflix and television, that we don’t want to go to the theater. I disagree with that summation entirely.

I think there’s a generation of theatre goers who just aren’t stupid. Our generation is not duped by shows which are extravaganzas but have no soul, which means we’re a lot pickier about what we want to see and experience. So I think that’s the most exciting thing for me, this return to the humanness of theatre — because that’s something film can’t give us.

Poster advertising iconic South African playwright Athol Fugard’s People Are Living There | Source: Rozanne McKenzie/Instagram

With film and television, you’re removed from the performer. You’re viewing them through a screen, oftentimes long after they’ve gone through the emotional journey to give you that scene. With the theatre, it’s all right there, and you’re living it in real time with the people on stage. And I think that’s what’s going to push us forward. Our generation is obsessed with our own lives and with the lives of others — so if we’re making theatre that lives, then we’ve got a strong few years coming.

Thank you so much for your time Ameera!

Ameera Conrad:

She graduated with distinction from UCT’s Drama Department in 2015 as a Theatre Maker (Honours). In her final year, she directed an adaptation of Nadia Davids’ The Healer, co-wrote and starred in the UCT Grahamstown National Arts Festival production Don’t Shoot the Harbinger (Winner: Best New Script), directed an extract from David Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow, and wrote, directed and performed live voice overs in her graduating production, bloom. Outside of the theatre world, Ameera has also been published in the UCT SAX Appeal (Dear White Boys™), the Cape Argus and Mahala Magazine.

Professionally, Ameera performed in Dr. Godenstein’s Man (written by Callum Tilbury, directed by Byron Bure), wrote a short play for Anthology: Young Bloods (dir. Louis Viljoen at the Alexander Bar), performed in What Remains (wr. Nadia Davids, dir. Jay Pather), performed at the Grahamstown National Arts Festival in People Beneath Our Feet (wr. Kiroshan Naidoo and Katya Mendelson, dir. Blythe Stuart Linger), performed in and co-curated The Fall at the Baxter Theatre, and was one of the recipients of the 2016 Theatre Arts Admin Collective’s Emerging Theatre Director’s Bursary, where she directed her self-written piece, Reparation. She will also appear in an episode of the new SyFy television series Blood Drive in 2017.