KATIE ROSENGARTEN

“When in Rome…

…die as the Romans die?” What might seem like a morbid spin on an otherwise commonly-overlooked phrase actually helps uncover the power of a tradition and tension underlying much of Rome’s allure for centuries: as a place to die. Again, this might seem strange for a city bustling with such apparent life: la città eterna, home to la bella vita (eh?). Yet, if one delves deeper into Rome’s multi-layered surface — which isn’t hard to do, given that the city has sustained itself by adopting an additive approach to its architectural landscape, reusing and repurposing ancient architectural predecessors for new use — one can see deeply rooted and longstanding signs of Rome’s true life source: its embrace of death. Another phrase that umbrellas much of this embrace, and one whose literal meaning is oft-mistranslated, is memento mori: (literally) remember to die, (i.e.) remember that you will die. This combination of two concepts that define us as humans — our precepts and capacities for memory and our predestined, looming deaths — are almost like magnetic forces with opposite charges. Memory allows people, or some fabrication of them, to live on, despite their factual departure from this world. Memory and mortality are twins, two sides of Janus’ door — and Roman society acknowledged this, knew this, and integrated this into their social fabric from its early foundations. Insofar as Rome is its people and its people are Rome, Rome’s death is that of its people and its peoples’ deaths are its own.

The Colosseum in Rome | Photo courtesy of the author

Rome is a paragon of the fight against death as the way into eternity.

How does a city go about embracing death? The fact alone that death is inevitable — even, at times, this looming presence — does not seem to mandate its daily recognition. So why intentionally weave death into the social fabric? One answer — an answer with tectonic tremors of influence across centuries and civilizations — is Augustan Rome.

Bust of Augustus in Palace Bevilacqua, Verona | Source: Wikipedia

“Augustan Rome” as an umbrella phrase can conjure myriad variables, facets of analysis, and strands of implication. For our purposes, Augustan Rome will simply mean the years — roughly 43 B.C. – 14 C.E. — during which Rome was under the influence of a singular political mind: Gaius Octavius Thurinus, a.k.a. “Octavianus” a.k.a “Augustus” (the honorific he gave himself via senatorial decree in 27 B.C., which comes from the Latin word augere, meaning “to increase,” implying in no uncertain terms that he was the great augmenter of Roman society while it underwent an existential crisis post-Julius Caesar). The final iteration of his title would be “Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus,” meaning “the Emperor Caesar Augustus Son of a God.” Subtle, right? Grandstanding names aside, Augustus’ growth into a divinized emperor was the result of the slow burn of key political decision after key political decision, a slow-and-steady-wins-the-race tactic that made his ascent (his augmentation, you might say) almost natural, obvious even, to a society whose regiphobia had rendered their political leadership vacuous and turbulent for upwards of nearly two decades. One such tactic was Augustus’ deceptively smooth transition in Rome’s structural governance from republican rule to rule under one citizen — the “first” citizen, the princeps. Augustus could not solidify power over Rome without concretizing the trust of its citizens (remember that symbiotic relationship between city and citizens). And so, by giving Rome an aesthetic rebirth, he gave its citizens a chance to embrace their own mortal narratives — in the form of their funerary monumenti.

Via Appia route (in white) traversing through the bottom of Italy’s boot towards the heel | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Funerary monumenti already played an essential part in republican Rome. Much of it lay outside the city limits, reflecting a longstanding understanding in many ancient societies, not just in Rome, that, for a mix of religious, mystical, and logistical reasons (…deteriorating bodies and public health don’t marry well…) the dead had to reside outside of the city. To this day, on the Via Appia, one can see the blueprint that Augustus drew on when encouraging a culture of individualized funerary architecture. These are not tombstones of the “Thriller”-graveyard type; these are monumenti, or small monuments (a word etymologically related to notions of “memory” — again, a pairing of memory and mortality). Steady urbanization and population growth proved a logistical and socio-political struggle for Rome, as it strove to allow individual citizens of various social strata their various funeral rights (religious and cultural) while not glorifying or hyper-celebrating one individual over another. Augustus himself, even two years before taking his name and inaugurating his role as princeps, began the process of building his own Mausoleum inside the city on the central, symbolic Campus Martius, a testament to the essential role of funerary architecture in Augustus’ (re)molding of Rome, and a marked example Augustus’ suave political style in integrating his own funeral legacy into the city’s architectural landscape, and calling upon a centuries-old, non-Roman architectural tradition. While not every Roman could afford the grandeur or influence of, say, a mausoleum with bronze inscriptions and giant obelisks, they could, within their financial and social limits, take their own stab at weaving their mortal memory into the Roman conscious.

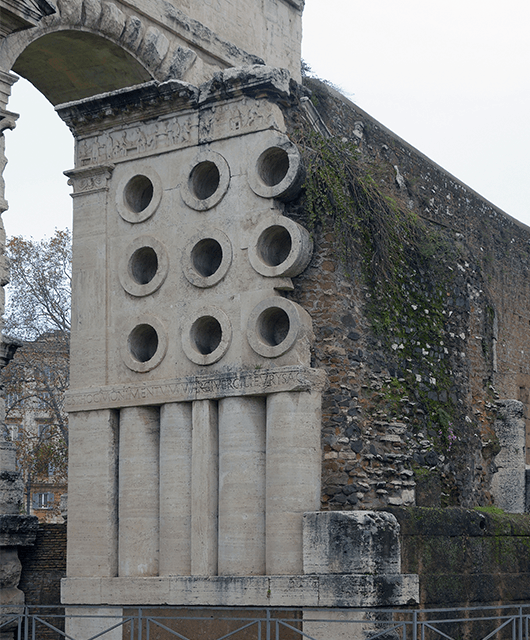

Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker in Rome | Source: Livioandronico2013/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

An epitomizing example of a Roman monumentum — and favorite of any student of an introductory Roman architecture class — is the Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker. Still snugly preserved as part of the modern-day Porta Maggiore, the colloquialized “Tomb of the Baker” has captivated audiences since its construction sometime between 30-20 B.C., right in the sweet spot when experimental takes on conventional funerary monuments took flight. Fit-to-form on a trapezoidal plot of land at the intersections of the Via Labicana and the Via Praenestina — two of the most well-trafficked roads near the ancient pomerium, or city limit — the tomb nowadays looks almost like a strange sculptural homage to the art of baking. A great example of Rome’s ability to move forward while taking pieces of the past along with it, the tomb has been chosen to survive on by ensuing centuries of Romans, likely due to its singularity and, funnily enough, its sense of humor. Visibility was on Eurysaces’ mind when designing the tomb: it is slightly raised on a platform of tufa stones, and the fact that it was built on a plot of land with such an unideal, non-rectangular shape suggests that location took primacy over architectural convenience or norm. In fact, the quirkiness of the shape might have even suited Eurysaces’ intentions for monumental idiosyncrasy.

[B]y giving Rome an aesthetic rebirth, [Augustus] gave its citizens a chance to embrace their own mortal narratives — in the form of their funerary monumenti.

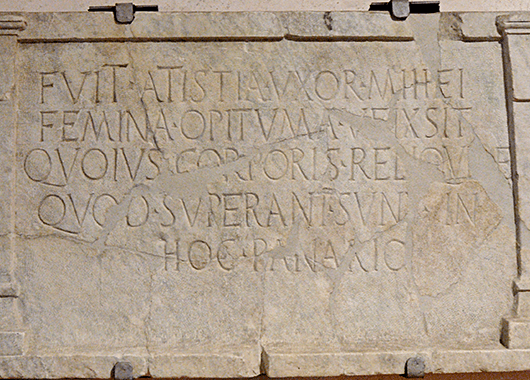

Funeral steele of Atistia, with the inscription saying “Atistia was my wife. She lived as an excellent woman, whose surviving remains are in this bread basket” | Source: Livioandronico2013/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

The tomb is oft-referred to as that “…of Eurysaces;” however, it truly is that of his wife, Atistia. We know this from one of the tomb’s two inscriptions, and yet one does not necessarily even know how to read those very inscriptions to understand the core purpose of the tomb and identity of the people who constructed it — a reminder that the majority of passersby would not be literate. A sculptural frieze encircles upper register, depicting scenes of bread making, kneading, and selling. The business of bread is emphasized, and there is reason to believe — based on evidence of other tombs and inscriptions found from the surrounding areas — that this was one of multiple tombs of or erected for bakers in this area. Furthermore, the actual, technical process of breadmaking is incorporated into the body of the tomb: the circular indentations on the upper three registers are kneading bowls — not too distant cousins from those that occupy bakery kitchens today — that have been lain sideways to act as a kind of patterned decoration. Those same kneading bowls are, one register below, stacked atop one another to serve as columns variegated with rectangular blocks. If it weren’t clear enough already what the “it” of the tomb is, the same inscription that identifies the tomb as belonging to Eurysaces’ wife Atistia remarks that she has been buried “in hoc panario;” — “in this breadbasket.” Romantic, right?

Bakery relief on the frieze of the Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker | Source: Livioandronico2013/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

The second inscription on the tomb, that encircles the middle section of the travertine stone, declares: EST HOC MONIMENTUM MARCEI VERGILEI EURYSACIS PISTORIS, REDEMPTORIS, APPARET; “This is the tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, it’s obvious.” Adding his name to the inscription, on a tomb for his wife, might seem intrusive or egotistical to the modern-day eye, but there is a practical reason for it. Eurysaces likely was a member of an increasingly populous sector of Roman society, the liberti, or freedmen, who earned their monetary freedom from their previous status as slaves. This gives greater weight to the second epithet redemptor[is], or contractor — implying that not only is he a baker himself, but possibly a leader of a network or company of bakers. As such, Eurysaces’ self-reference in the inscription provides an etiology for the very existence of such a tomb; without Eurysaces’ social ascent and professional success, there would be no tomb. The concluding “apparet” had long proved a grammatical quandary for interpreters of the tomb, until the idea that it could simply be a quippy, wondrously modernized aside — “…it’s obvious” — perfectly fit the tone of the tomb: taking the medium simultaneously to its comedic and generic limits. One’s monumentum acted as a conversational medium between the deceased and the viewer, and as curator of his wife’s tomb, Eurysaces prioritized accessibility, legibility, and humor to the effect that one cannot walk away without hearing a resounding, poignant note about the identities we strive to build in life and (in this case, literally) concretize in death.

While not every Roman could afford the grandeur or influence of, say, a mausoleum with bronze inscriptions and giant obelisks, they could, within their financial and social limits, take their own stab at weaving their mortal memory into the Roman conscious.

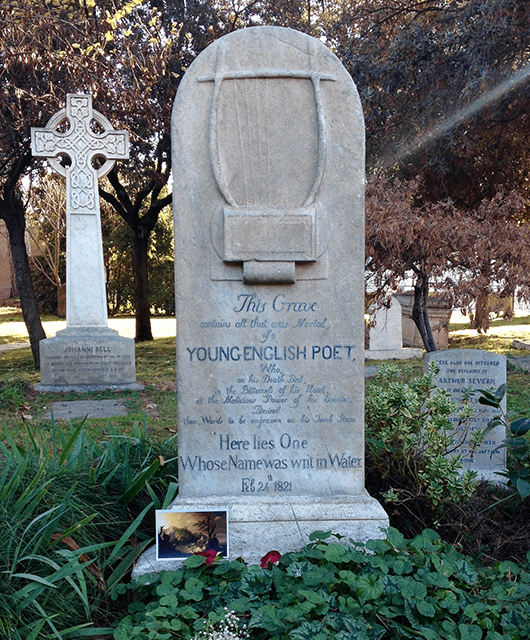

John Keats’ tombstone in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome | Photo courtesy of the author

Rome’s embrace of death is a necessary one, not one of two lovers — such as the Romantics’ embrace of death in their poetry, well-exemplified by Keats, a well-documented Romano-phile. Nor is Rome’s embrace of death one that cedes to death’s eternal “forgetfulness divine” or “save[s]…from curious conscious”, to use Keats’ words from his 1819 poem To Sleep. For all his classical training and familiarity with Greek and Roman myth, Keats’ Romantic concept of death — that it was the resolve from the pains of daily woes, that it was a pleasurable descent into oblivion — arguably contrasts on a fundamental level with the Roman concept of death we see evidenced in a tomb such as Eurysaces’, which is an admirable fight against oblivion, against anonymity. To solidify the contrast one step further, Keats’ own tombstone, which remains in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome, 4 kilometers southwest from Eurysaces’, concludes with the following line: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” The words are engraved under a lyre with seemingly incomplete or possibly broken strings, and are reinforced by the fact that the tomb does not bear Keats’ own name anywhere; the only other cue is the phrase “…a young English poet…” — yet another attempt at generalized anonymity, and an epitomization of the ephemeralism of life espoused in Keats’ poetry. Although assembled after Keats’ death by a friend, Joseph Severn, epistolary documentation around the time of Keats’ death indicates that the tombstone’s final form largely succeeded in fulfilling Keats’ wishes for it. It’s with the same purposefulness that Eurysaces filled his tomb to the brim with iconographic and verbal cues at his identity and life story that Keats deprived his tomb of such identifiers; instead, anonymity reigns and begins the process of erasing Keats from the mortal world, taking away his name first (all despite the deep irony of his now memorialized, posthumous fame). For Keats, mortality was freedom from an anxious, ailed life; for Eurysaces, mortality was a chance to demonstrate and record his life’s achievements for posterity. Both died in the same city, yet the latter died a truly Roman death while the other, one could say, died a definitionally Romantic death.

View of Rome from the ruins of Trajan Market | Photo courtesy of the author

In a discussion of ancient notions of mortality, or really any discussion of mortality, we run a great risk of projection. Mortality is one of the few facts of existence that have ruled for all of time, and in that sense both unify us in the collective cloak of humanity and increase the difficulty with which we can distance our own singular relationships with mortality so that we can examine others’. Rome provides a unique opportunity to study attitudes toward death and its aftermath, thanks in large part to its seemingly paradoxical integration of death into its very being. Rome is a paragon of the fight against death as the way into eternity.