NORA ROSENGARTEN

The stage is empty. The crowd is hushed, waiting. The orchestra begins a brusque march of horns and violins. A dancer steps out from the wings en pointe, her tutu a flash of bright white. Her legs and feet pound a frenzied beat while her arms flutter back and forth in a quick rhythm. Wings flapping forward back forward back as feet and knees hum. For less than a second, she dances alone. A foot reaches forward and, behind her, an identical foot and leg extend from the wings onto the stage. A second swan arrives on her pointes. As one, the two right feet step forward, repeating this same sequence now as a duet. Then as a trio. A quartet. One after another they claim their spots in carefully organized lines of rows and columns, until the stage is full. Each dancer is identical to the others in every fiber of her being. They seem to move as one creature. Every leg is extended to the same height, heads darting from left to right in perfect synchrony.

Prince Siegfried arrives, crossbow in hand. He surveys the scene with anxiety. He is looking for one swan: Princess Odette. He knows she is here, but how will he find her? He lopes gracefully between lines of posing swans, examining each for a sign of Odette. The swans — as if in reaction to his failing search — begin to run in a dizzying circle around Siegfried, outstretched ankles and tendons tensing as they bounce on and off their pointes. They are a blur of white, whipping past too quickly for recognition. Yet even if they moved more slowly, this adjustment would only highlight the search’s futility. They are identical. Siegfried withdraws to the sidelines. The swans line up in tight diagonal rows across the stage from the intruder, arms pumping up and down violently. As the music crescendos, line after line of swans is added to these ranks. Their movements are frenetic yet precise, each arm extended to the same angle, raised at a designated height. The effect is dazzling. But where is Odette?

Like Siegfried, the audience searches the crowd for their loved ones. Dancers’ parents and friends will have to count entrances to know which dancer is theirs, and even then they will question whether they are watching the correct dancer. The swans stop suddenly. Siegfried advances, reaching out a hand to touch a swan. Is it her? Every swan abruptly jump to a new pose, reacting as though his cold hand had brushed each cheek in the same instant. Siegfried retreats, chastened.

Ballet Russes’ Swan Lake | Source: National Library of Australia/Flickr

A figure emerges, initially indistinguishable from the others. She stands in front of the squadron of swans like a ship’s figurehead, emblematic of those who stand behind her. Deftly, she raises her arms about her head and salutes Siegfried with a quick turn. She throws wide her arms, baring her breast to his crossbow. It is Odette. She has identified herself as an individual distinct from the sea of swans. She dances alone.

Ballet is — perhaps more than any other art form — reliant on synchrony of movement as a tool for constructing meaning.

Throughout Swan Lake, thirty-two dancers in white tutus perform in unison. They are called the corps de ballet (literally the “body of the ballet”). These dancers are characters without individuality that establish the setting and mark the passage of the plot for both the main characters and the audience. They are onstage for almost the entire ballet, often posed along the sidelines like statues, then jumping to life again for their next dance. Their bodies create one geometrically perfect tableau after another, crossing the stage with restrained, precise movements so that they will not overshadow the main players’ solos and variations. In some ballets, the corps members change costumes and styles of dance to travel from the land of the living into the dead (Giselle) or to move from fairies to entertainers (Sleeping Beauty). No matter their form, they dance as one. Their unity survives transformation; it is elemental.

A second’s hesitation, a slight misstep and the vision is destroyed.

Source: Library of Congress/Flickr

This synthesis is created through hours of rehearsal and scrutiny. Ballet is — perhaps more than any other art form — reliant on synchrony of movement as a tool for constructing meaning. A premium is placed on dancing together, starting with the smallest ballerinas who are taught to count music with eyes glued first to their teacher, then to their peers. To climb through the hierarchy to the ranks of a principal or soloist, the dancer must first master the corps movements. The steps the corps perform are simple yet dancing with the corps is believed to be more challenging than a soloist or principal role. A second’s hesitation, a slight misstep and the vision is destroyed. Dancers in the corps learn to feel one another’s bodies in space, and so to move neither proactively, nor reactively, but actively. They inhale and exhale at precise moments in the choreography. They breathe as one.

Every leg is extended to the same height, heads darting from left to right in perfect synchrony.

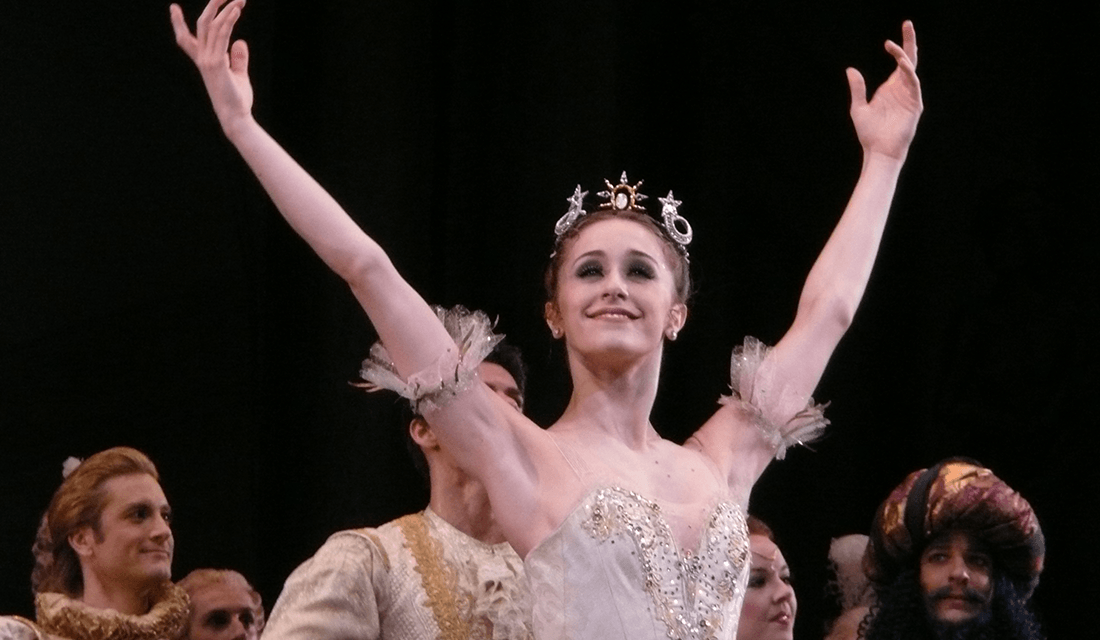

There is elation and wild joy in moving together, in playing one’s part in this harmonious triumph. But there is also incredible restraint. The dancer whose leg typically extends to her ear must lower it to a parallel line with the floor to match her fellow corps members. If a dancer is having an especially good day in terms of balance, she still must fall from her pointe at the specified beat rather than hover in the air a moment too long. When a dancer dances alone, these movements are malleable, subject to the varying physical state or mood of the dancer. On one evening Marianela Nuñez (a principal with the Royal Ballet) might do three pirouettes in Don Quixote, but the next night in the same section she could perform five without altering her choreography dramatically, or giving any kind of notice to anyone, aside from an additional applause or bravura from her audience. Her actions are her own. The corps is the same night after night. No changes.

Marianela Núñez in Royal Ballet’s Sleeping Beauty | Source: Ruskin/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-4.0)

The corps de ballet can be traced back to the French Revolution. Women of the Revolution dressed in simple white tunics (modeled after antiquity) to symbolize a virtuous, pure, and incorruptible society. Before this, the ballet’s corps was composed of featured characters with distinct personalities who hovered around the fringes of the action. The women of the Revolution, while draping garlands over busts of Marat or accompanying Lady Reason during her festival, established a new aesthetic. After the revolution, the corps was all female and indistinguishable from one another. They represented the community and society’s claim over the individual. Groups of these young women appeared prominently in almost all Revolutionary festivals and celebrations, moving gracefully through space without speaking. Unity gave them moral authority and political identity, which was then transferred onto the ballet stage.

In appearance and emotional register, both the corps and the Greek chorus occupy a subdued presence for their storytelling roles.

20th-century Rendition of Greek Chorus | Source: Library of Congress/Flickr

The corps de ballet finds a counterpart in the Greek chorus. The word “chorus” comes from the Greek χορεύω (choreuo), which means “to dance.” In his Poetics, Aristotle theorizes that the earliest Greek “plays” were a formalization of stories that had been told orally for hundreds of years. Stories were passed on from generation to generation, evolving with each successive iteration. Since there is no written record of these performances, it is impossible to be certain what transpired, but Aristotle theorizes the chorus would dance and sing to tell the tale. Individual characters gradually emerged from this mass of humanity (see author’s notes at the end of this article). By synthesizing the storyteller into one entity with many mouths, the Greeks elevated traditional storytelling methods. The narrator’s multiplicity increases reliability and underscores the parallel between the chorus onstage and the audience in the seats. Although the nature of the Greek chorus’ movements cannot be known, their words remain for us to study. It is clear that the plays required perfect unity in speech and song; anything less would obstruct meaning. Much as the corps members’ restrained movements provide a setting and move along the plot, the Greek chorus’ clear and synced speech mediated the audience’s experience of the play. Both bodies are a transparent layer between action and audience, not fully consumed by the events and their emotions, but able to affect the players in their pursuits.

Royal Ballet’s 1958 Swan Lake | Source: State Library of New South Wales/Flickr

While Odette and Siegfried experience fantastic love and destiny in one another’s arms, the thirty-two swans observe, nonplussed. Like most corps de ballet, they do not perform strong emotions. The swans are certainly melancholic. Their vague gloom is communicated through small, simple movements, which are so unlike Odette’s tragic, painstakingly slow and technically brilliant adagios, and the iconic “Black Swan” Odile’s flashy fouettés and wild leaps. The corps does not emote to the same extent as the solo dancer, either through movement or facial expression. And, just like the Greek chorus in its masks and robes, the corps members go to great pains to achieve a visual effect of one figure multiplied. Dancers eschew nail polish, tattoos, and jewelry. Those with short hair sport fake ballet buns. Pointe shoes are dyed and colored to match one another. Some dancers even cover birthmarks with makeup to obscure any sense of individuation. In appearance and emotional register, both the corps and the Greek chorus occupy a subdued presence for their storytelling roles.

The Nutcracker‘s Snowflake Waltz, as performed by the New York City Ballet in 1954 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Does synchrony require muted affect? Is the corps’ efficacy reliant on a diminished emotional register?

There are many possible explanations for the unified emotional tenor of the corps.

Firstly, the visceral visual effect of synchronized movement is powerful. The scene from Swan Lake described above uses the multiplicity of dancers to create a beautiful scene while also propelling the plot forward. The steps and bodies feel pure, organized, and collected. They move as one and it is breathtaking. Introducing emotion into the steps might distort that purity, like filling a slender glass vial with a volatile liquid that jumps, spews, and explodes. A recipe for disaster.

Effective storytelling requires moments of unity in stark contrast with explosions of individuality.

Ballet Russes’ 1940 Les Sylphides | Source: National Library of Australia/Flickr

From a practical perspective, synchronizing the experience of intense emotion is near impossible. Performed emotion is deeply personal and nearly impossible to imitate, whether within a single performance or from performance to performance. A singular, unique portrayal of an emotion, particularly when rooted in the dancer’s experience of that emotion, cannot be taught. One dancer’s Giselle may be fragile and delicate, while another dancer’s may highlight the mischievous, flirtatious nature of the titular peasant. Decisions about emotive expression are the realm of soloists and principals. Just as simple steps are easier to coordinate, simpler emotions are reproducible with greater consistently than nuanced expressions of desire, love, and suicide, as in the case of the lead ballerinas in both Giselle and Swan Lake. The corps emotes on a lower register, like fog that creeps across a stage or gentle beams of sunlight. It’s not enough to tell a story, but it provides a place to start; a jumping off point for the individuals around whom the action is focused.

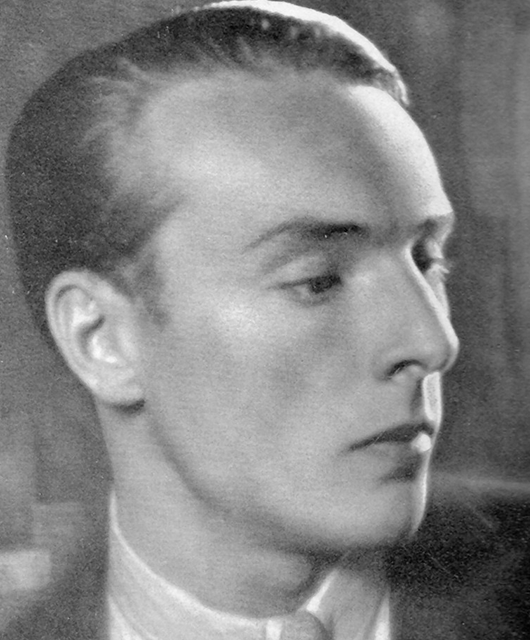

George Balanchine | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Neither of these possible explanations fully account for the corps’ endurance from ancient Greece to 18th-century France and all the way through the present. George Balanchine — the greatest ballet choreographer of the 20th-century — employed the traditional, emotionally reserved corps in several of his ballets, most notably Jewels. Modern restagings of classical ballets have tweaked choreography, setting, and style but no directors have dared disrupt the corps from their traditional methods of expression. This decision is considered, not automatic. The corps’ unity has been preserved over hundreds of years: to what effect? in service of what deeper artistic goals?

The corps emotes on a lower register, like fog that creeps across a stage or gentle beams of sunlight.

These groups of bodies are suspended on a tightrope between being characters and being audience members. They float, liminally poised between the two. Effective storytelling requires moments of unity in stark contrast with explosions of individuality. Individual expression is more significant and powerful when juxtaposed against the common behavior and expression of the corps and their audience. The corps are engaged in — but not devastated by — the action. Like the audience, they cannot anticipate what comes next. In Seneca’s tragic Thyestes the chorus famously turns to the audience and demands, “Quid nunc?” or “What next?” (a colloquialism rather than a direct translation). The sculptural bodies of the corps, which line the stage, shifting from passive position to passive position, pose the same question. What will happen next? When will we be moved to dance again? They are more object and backdrop and context than character. To emote extensively would be too persuasive, too presumptuous. The corps — like the chorus — instigates without strictly dictating their audience’s emotions. Their role is environmental rather than instructional. They are reactive, rapt observers, just like the audience. The corps is not held hostage by the action; at the end of the ballet they are free to go.

Like the audience, the corps is bystander to the action through the end.

At the end of Swan Lake Siegfried and Odette commit suicide by plunging into the lake’s icy waters. They choose to end their lives and move to the heavens as lovers rather than live in the world without one another. Despite the corps’ association with Odette, her suicide leaves them unscathed. After Odette and Siegfried ascend to the afterlife, the corps is left alone onstage. They turn their backs to the audience, wings undulating gentle back and forth. As one, they drop to their knees, throw their arms overhead and bend backwards triumphantly. When the music climaxes, the swans fall forward, bowing so low that they disappear into a cloud of fog. They become elemental. It is as though the whole thing was a dream. Like the audience, the corps is bystander to the action through the end. They finish the ballet oriented the same way as their observers, eyes burning into the depths of the stage where Odette and Siegfried recently disappeared. They search for answers alongside the audience. This moment — the ballet’s close — is the greatest “What next” moment of all. The corps’ bodies direct this question to their audience. What next for us? What next for you? This question breaks the spell of unity the ballet cast. The curtain will close. The house lights will go up. Dancers will disperse. Audience will chatter. Daily life, muddled and unclear, takes over again. “What next?” is a reminder of the impossibility of such unity. Unsustainable, yet exquisite.

Author’s Notes:

- The three main Athenian tragedians of the 5th-century are (chronologically) Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Interestingly, the number of main characters that are onstage at a time increases incrementally from Aeschylus to Euripides. The chorus are always the first and final occupants of the stage. In Aeschylus’ plays, there are never more than two individual characters onstage at a time, whereas Sophocles has a maximum of three, and Euripides never features more than five. This evolution is used to support Aristotle’s theory that early Greek plays were the chorus — and the individual characters and dialogues evolved from there one solo song at a time.

- Gratitude to Katherine Rosengarten for her knowledge of Greek culture, language, and tragedies.