ALEXANDRA REALE

The year is 1991, and on a warm summer night a group of tall, fit women gather in a tasteful studio in Santa Monica. They remove sunglasses from tan faces, some revealing white outlines around their eyes and noses, souvenirs of hours spent in the sun, as they cross long legs and settle in around the table. They look charmingly out of place inside, like exotic birds trapped temporarily in a cage. Many are chatting animatedly, but the cheery atmosphere turns businesslike as notebooks are opened and pens are uncapped. Discussions and debates begin, and as an evening breeze ruffles the tree-lined street outside, the women grow totally absorbed by their tasks. Suddenly is it one in the morning; families and the work of the following day beckon. They stop what they are doing, promising to see each other the following week, and get in their cars for home.

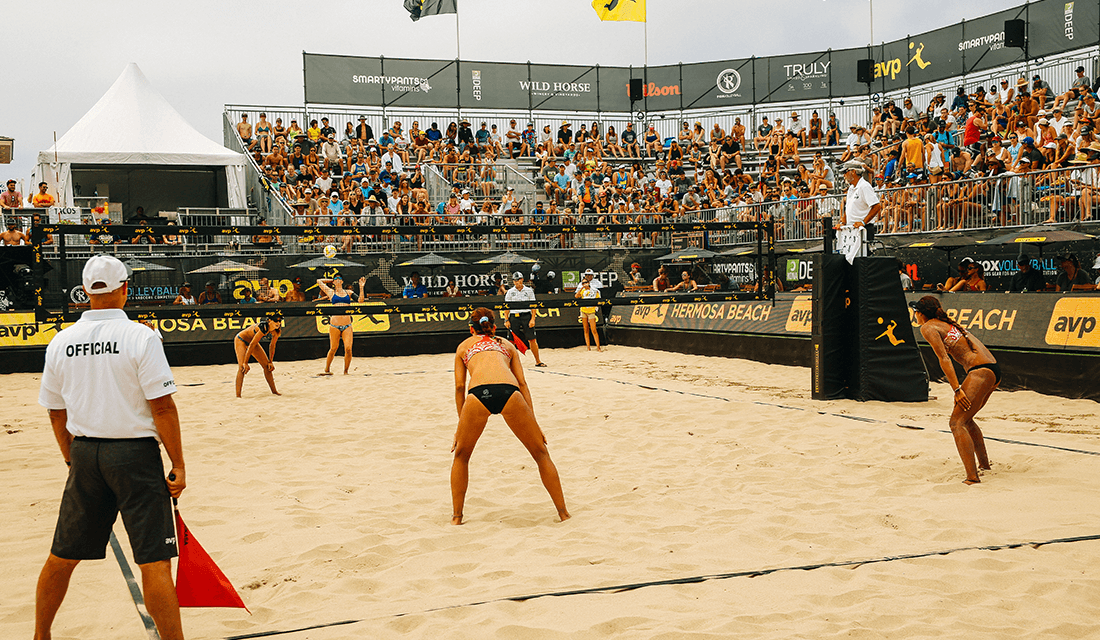

1997 WPVA Hermosa Final | Source: LLee’s ClassicAVP/YouTube

These women have devoted this evening to a cause they care deeply about. They are board members for an entity called the Women’s Professional Volleyball Association, or WPVA. The WPVA was the premier professional beach volleyball tour for women in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, and its purpose was to give intrepid female doubles teams a chance to compete in locations across the U.S. for prize money and maybe a little bit of fame. Week after week teams of two showed up at locations like Hermosa Beach, Will Rogers State Beach, Miami Beach, or Atlantic City, shaking off sleepiness and clutching laundry bags of volleyballs. They dug their umbrellas into the sand, snacked on sandwiches and protein bars, and prepared themselves for long days of competition. Making it to the end of one of these tournaments required a camel-like ability to stay hydrated and endure the elements of sand, wind, and sun, all while besting opponents in grueling games to (at that time) fifteen. The idyllic settings of these competitions — glittering water, colorful canopies, women in bikinis, a landed complement to The Beach Boys’ surfing paradise — belied the grit and toughness required to find success.

It is possible that there was no beach volleyball-specific reason that female athletes found themselves fighting tooth and nail for mere real estate on the beach […] but the fact remains that the beginnings of professional beach volleyball were for women a constant struggle to be taken seriously and paid equally.

In beach volleyball, there are two players on a team, no subs. A net like a tennis net on stilts divides the rectangular court, which is delineated by ropes, into two opposing sides, classically thirty feet by thirty feet. The two players on each side stand about ten feet laterally from each other, each person floating in the center of their quarter of the total court. From above the setup is domino-like. Bare toes grip sand as teammates scramble around on their side, using the up-to-three hits they’re allowed to move the ball over the net to the other team’s side of the court, with the intention to get the ball onto their competitors’ patch of sand. As the skill level increases, the trickiness of this endeavor skyrockets, as defenders’ ability to recognize patterns and movements in offensive tactics gets better and better. It is a game that requires exceptional hand-eye coordination and fast-twitch muscles, plus a zen-like short-term memory; the best players discard errors and move on to the next point. Though scrappier and scruffier than its indoor sister, the beach game comes with its own set of skills to be practiced, refined, and in turn coached to others. For a certain set, it became much more than a fun pastime to accompany the family picnic: they saw in it a passion and purpose, even a golden opportunity.

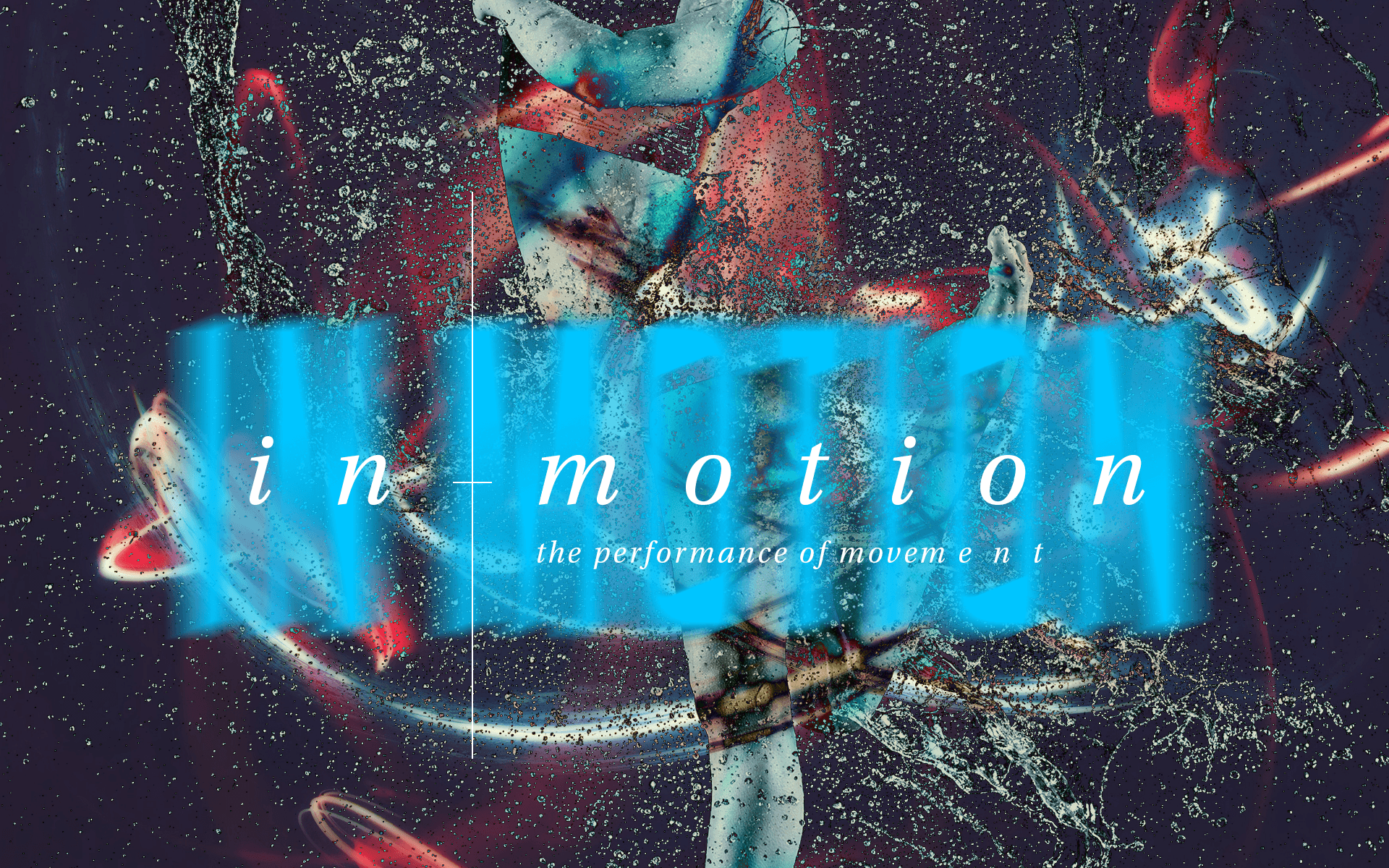

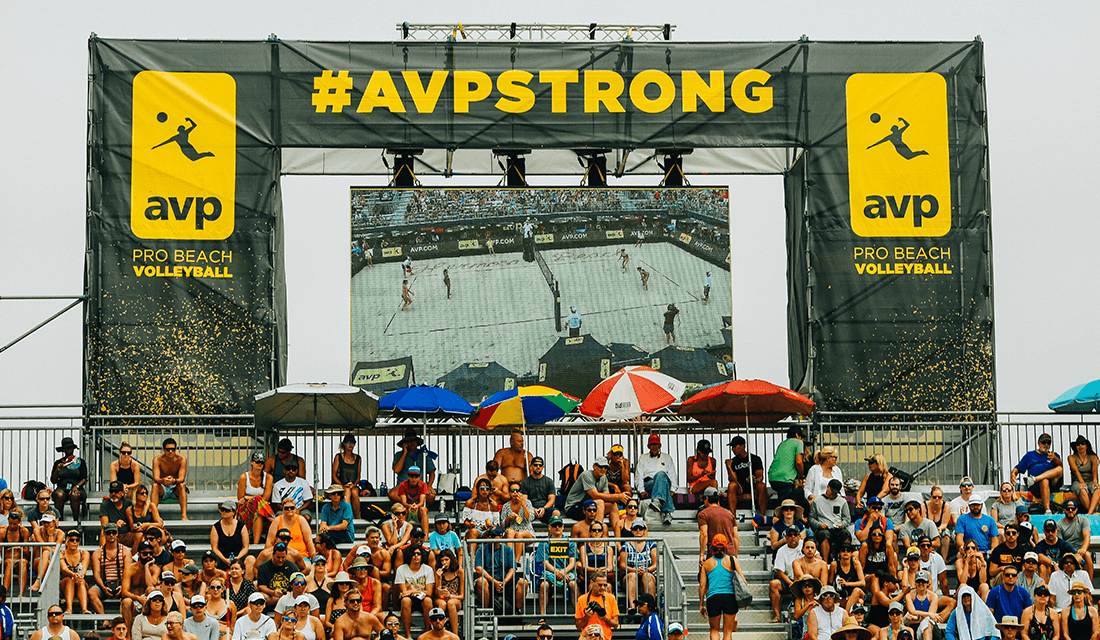

AVP Hermosa Beach Open 2017 | Source: MF Solutions/Flickr (CC-BY-2.0)

The men and women who saw the potential in this sport wanted to compete at a high level, to test their physical limits, but more importantly, they wanted to earn a living doing so. The only way to get this off the ground was to form professional tours, à la the NBA or NFL, but this would prove difficult. Beach volleyball, lacking the historical and cultural inculcation of basketball or football, had to start from the very beginning. The California Beach Volleyball Association, born in 1965, was among the first tours to nurture the sport, and what followed was a cascade of acronyms: the BVA, the AVP, and the WPVA. As the sport gained momentum and popularity, thanks to legendary performances by the likes of Jim Menges and Ron von Hagen, sponsors like Jose Cuervo and Miller began to step up. With more resources came more opportunities to attract talent and put on tournaments, and the AVP (Association of Volleyball Professionals) proved itself the strongest player in this game. By 1985, male athletes were competing for, in some AVP tournaments, a winning purse of $275,000. They weren’t making NFL salaries by any stretch of the imagination, but the men competed for good prize money and enjoyed plentiful opportunities to compete.

Helen Reale | Photo courtesy of The Author

The women, meanwhile, were off to a rocky start. It is possible that there was no beach volleyball-specific reason that female athletes found themselves fighting tooth and nail for mere real estate on the beach — Billie Jean King was fighting this fight in tennis at the same time — but the fact remains that the beginnings of professional beach volleyball were for women a constant struggle to be taken seriously and paid equally. My mother Helen Reale, who played on the WPVA once it formed and was treasurer of the board, remembers competing in tournaments on the East Coast in the late eighties alongside the men:

“We’d win our playoff games and walk all the way back to the main tournament tent, expecting to play in front of the crowd that’s gathered for the men’s final, and the tournament director would go, ‘just go play your final over there,’ and we’d hike all the way back to Siberia.”

She says they were a “sideshow,” an afterthought, not competitors in their own right. Though they knew the sport was popular and approachable, regardless of the gender of the players, the women in beach volleyball saw the writing on the wall: to get some separation from the men, they had to form their own tour, and thus in 1986, the WPVA was born.

Making the tour work was tricky; there were sponsors to woo, prizes to offer, operations managers to employ, even TV rights to pay (the men’s tour did not have this issue), and you can’t charge people for entering a public beach. Barbra Fontana, an Olympic medalist in beach volleyball and somewhat reluctant president of the WPVA, took a reasonable stance on the matter:

“The athletes were super passionate about their love of the game; however, that’s not a business model. You had passionate people who believed in the product but didn’t know how to create the infrastructure.”

To stay solvent the women of the tour had to run extremely lean, and the united front which had strengthened them in forming their own tour quickly dissolved. Their limited funds uncovered fundamental ideological differences in opinion among the women of the tour, and the board found themselves locked in circular arguments. Should a large portion of competing teams earn money, or should only the very top performers earn? Many top performers advocated for increasing their own salaries for winning tournaments, or taking second or third — this was their career and they were not interested in taking desk jobs — while those not competing for top spots emphasized paying prize money down from the top all the way to teams who took, for example, seventeenth. This meant that the cost of entering a tournament would not be an automatic loss, and, theoretically it would encourage more teams to participate.

WPVA (Women’s Volleyball) 1994 Ft. Lauderdale Final | Source: LLee’s ClassicAVP/YouTube

It came down to an elites versus grassroots argument, and the self-interest of the larger group proved more compelling. In the back of their collective mind floated ideas about expanding opportunities in the sport, making it more accessible for young athletes. Perhaps if more teams saw an opportunity to make some money without attempting to unseat an elite player, they would be more likely to sign up to play, which would contribute to the grassroots growth of beach volleyball. Plus, crucially for the short-term, these newer teams’ entry fees would help float the costs of the tournament.

Barbra, a rare elite player who took a longer view of the situation, remembers presenting the business plan that the board eventually came up with to the other athletes: the WPVA had been running on credit for too long, and the money which many players thought they were going to see did not actually exist. In order to continue to put on tournaments, they had to forgive the debt, and elites would have to reduce their prize money. They told the athletes frankly that they would have to sacrifice some earning potential, but that they would run in the black and build the sport, which would be better in the long-term for everyone involved. This was just convincing enough, and the WPVA limped along, buoyed not so much by seamless agreement as civil discord.

The men and women who saw the potential in this sport wanted to compete at a high level, to test their physical limits, but more importantly, they wanted to earn a living doing so.

For awhile this was sustainable. Female beach volleyball players began to gain some traction in audiences, not just the attention of curious passersby, and the women saw some growth in their sport. Dennie Shupryt-Knoop, who uprooted her East Coast life and moved to Southern California to train and compete in beach volleyball, recognized that the tour needed committed sponsors or it would fade away, and her tenure as a board member found her constantly thinking of ways to turn the market to the WPVA’s advantage. But it wasn’t just the board who had to think in shortcuts and solutions. The players themselves had accepted the compromises that were necessary for solvency, but this meant they were not making enough to be truly “professional.” They found other ways to make ends meet: they picked up individual sponsorships with local and national brands, they worked side jobs, and some of them worked full-time and snuck in training in the early mornings or evenings — weekend warriors with a deep passion for the sport.

The board continued to work on the issues that confronted the players, some of which were ahead of their time, and could potentially only happen in a boardroom dominated by women: my mom says that they frequently discussed a kind of “maternity leave,” wherein pregnant players who had established a high ranking earlier in their career could take a break from the tour to take care of their child and come back roughly where they left off. It was exciting and full of possibility, but this time in women’s beach volleyball was one of the crests in a wave that would inevitably dip down below the x-axis again.

Despite the interesting conversations and the progress they had made, the WPVA was only temporarily patched up — soon leaks were springing, and the board members had to look for new solutions. They were more seasoned now, and had established themselves as a force in the beach volleyball world, but the fact remained that the WPVA was struggling with its finances. The women looked across the beach to their male counterparts on the AVP, seeing a tour that was better positioned to weather the storm. In 1993, the AVP hosted its first women’s competition alongside the men, and to this day both men and women are featured. They play for the same winnings, no questions asked. In many ways, this is a stunning victory, but the former board members of the WPVA are shrewd; they have seen what it takes to keep their sport alive, and they know that this equanimity does not come without a cost. Only this time around, the issue is collective: male and female beach volleyball players worry together about how to make the AVP, which struggles — like its predecessors — to hold down sponsors and get TV time; to be profitable.

AVP Hermosa Beach Open 2017 | Source: MF Solutions/Flickr (CC-BY-2.0)

The AVP has its own battles to fight, but the grassroots efforts of, among others, the board of the WPVA has its own interesting trickles in the world of beach volleyball, now thirty years later. Misty May-Treanor and Kerri Walsh-Jennings, three-time Olympic gold medalists in beach volleyball and among the most dominant athletes of all time, were only teenagers when the turbulent opening act of their sport was unfolding. Now we will remember them as sports legends. Sand volleyball is now recognized as a Division 1 college sport for women, and perhaps in response, beach volleyball clubs have begun to spring up throughout Southern California, seeking to train enthusiastic young players who may have a chance to go to study and play at the next level.

Misty May Treanor and Kerri Walsh, Great Moments In Team USA History | Source: © Team USA/YouTube

Beach volleyball is no longer just a recreational game to accompany a barbecue; it’s a (mostly) thriving professional sport, growing bigger each year, and facing new challenges with every step forward. My mom Helen, who crunched numbers for the board and argued over prize money and sponsorship and maternity leave, is coaching her high school beach volleyball team in Southern California regional playoffs right now. In the fall, she will watch for the third time as one of her players heads off to play Division 1 sand volleyball, an opportunity that was totally unfathomable just a few years ago. The discussions that she and Dennie and Barbra had in that studio in Santa Monica turned out to be about more than just cutting costs and keeping their tour alive: they were shaping history — a sweaty, sandy, joyous corner of it.

The author would like to especially thank Barbra Fontana, Dennie Shupryt-Knoop, and Helen Reale for agreeing to let her pester them with questions, and would like them to know that she admires them all greatly.