TENAYA CAMPBELL

Spoken by more than 200 million people worldwide, French is one of the most widely used languages in the world. For hundreds of years, it was the main language of business and diplomacy in Europe and is still a major player in the modern linguistic era. French is part of the Romance family of languages, along with Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian (and lots of others). Despite the variety of Romance languages, somehow French has come to be known as “the language of love.” This correlation has less to do with any inherent love or passion in the language (sorry) and everything to do with how it developed and spread in popularity.

Source: K-International

The idea goes that every language developed out of some proto-, or mother, language. This theory is mainly rooted in the similarity between words across very diverse languages (take, “mama” and “papa” for example, which are the same in Greek, Latin, German, English, Sanskrit, and Celtic). In the case of French, the language developed from Latin by way of the Gauls and the Franks. Language is a way to share information with other people, and when many groups cohabitate they end up sharing words as a way to more effectively communicate with each other. Over the course of hundreds of years, while the territory that is now France changed hands between the Celts (Gauls), the Romans, and the Franks, the languages mixed and created modern French. The reputation as the language of love enters the scene later during the Middle Ages with the rise of troubadours and their chivalric poetry.

The incredibly popular Franco-Belgian comic book series Asterix depicts the titular character and his band of merry Gauls (and a potion-making Druid to boot) fighting against Roman occupation | Source: Amazon

At the beginning of the story of French, there were the Celts. In the 1st millennium, they arrived in what is now France and took over the native population. They spoke a Celtic language — Gaulish — which remained the main language of communication until the Romans showed up in the 2nd-century B.C.E. Some words French speakers might recognize from Gaulish include aller (to go), cheval (horse), mouton (sheep), and alouette (lark). Julius Caesar conquered France around 50 B.C.E. and brought Latin with him. The local Celtic tribes assimilated to the new Roman culture and the elite classes begin speaking Latin. The Romans did not force their language on the conquered populations, but all government and law enforcement was conducted in Latin and the language carried a high social value. For anyone who wanted to advance his or her social position or be involved in public service, it was important to speak and read Latin. Classical Latin thus was a sign of status and the rest of the population used Vulgar Latin, the mother of the modern Romance languages. By the 4th- and 5th- centuries Gaulish had totally disappeared from France (except for one stronghold in Normandy) and the region had officially become Latinate.

As a language, Vulgar Latin was a spoken Latin that varied depending on geographic region and had no standard written form. To draw a comparison to language today Vulgar Latin would be the equivalent of African-American Vernacular English in the U.S. or the Cockney English dialect in the U.K. It was a version of the language that was related to the written or standard form of Latin but that had diverged substantially. To someone who was educated in Classical Latin, it would seem as though Vulgar Latin speakers were breaking the rules or speaking incorrect Latin, but they were actually following different grammatical and phonological rules. The vast geographic spread of the Roman Empire also meant that there were lots of versions of Vulgar Latin since every region had a different cultural and linguistic background. The early versions of the Romance languages we know today started basically as creoles of Vulgar Latin and whatever other languages were spoken in the region.

The Roman Empire in 117 A.D. | Source: Ancient History Encyclopedia

19th-century depiction of the 5th to 8th-century Franks | Source: Wikimedia Commons

For two centuries the elite classes and clergy spoke Classical Latin and the commoners spoke regional versions of Vulgar Latin. Then, in the early 400s, C.E. the Franks came on the scene (they will give France its name) and in 430 they settled in the region that is now Belgium. They spoke Frankish, which was an early Germanic language unrelated to Gaulish and Vulgar Latin. By the 470s, the Roman Empire had weakened and in 476 a Roman soldier named Odoacer deposed of the Emperor Romulus Augustulus and proclaimed himself the ruler of Italy. This is considered by some to be the end of the Roman Empire, although it took many more years for the full dissolution of centralized power. The Franks capitalized on this transfer of power by moving south into Gaul. King Clovis I of the Franks took over southern France and northern Spain. In an uncharacteristic move, the conquerors started speaking the language of the conquered and the Franks began speaking Vulgar Latin. They remained bilingual in Frankish until the 10th-century and about 10% of modern French vocabulary comes from Frankish, including fauteuil (armchair), gant (glove), and orgeuil (pride). Frankish also lent a new grammatical structure and pronunciation to the Vulgar Latin dialect that would become French. Because of the Franks, French is the most Germanic of the modern Romance languages.

To someone who was educated in Classical Latin, it would seem as though Vulgar Latin speakers were breaking the rules or speaking incorrect Latin, but they were actually following different grammatical and phonological rules.

While the common people spoke regional creoles, the upper classes and clergy continued reading, writing, and studying in Classical Latin. Any published literature including religious texts and poetry would have been written in Classical Latin and religious ceremonies performed in it. Once the clergy began to move towards the vernacular we have evidence that the vernacular was actually becoming an independent and distinct language. The earliest evidence we have of the clergy beginning to speak the vernacular comes from the 8th-century, in the Gloses de Richenau. This document was a glossary of 1,300 words of Latin and Vulgar Latin that showed people were now relying on the vernacular in order to make sense of the Classical. Then, in 813, at the council of Tours, priests were officially encouraged to preach in the vernacular rather than in Classical Latin. This marks a major shift in the history of French, because it tells us that by the 8th-century Vulgar Latin had diverged so much from Classical Latin that they were no longer mutually intelligible, and that people were not bilingual. Vulgar Latin had officially become a language distinct from Classical and was called Romance. The name came from the expression used in Vulgar Latin to refer to the language which was “to speak Roman,” as opposed “to speak Latin.”

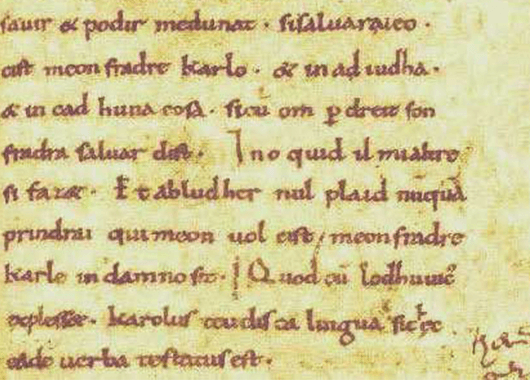

A portion of the Oaths of Strasbourg in Old French | Source: Wikimedia Commons

French emerges as a language separate from the other Romance dialects around the 840s. In 840, Charlemagne’s three grandsons — Louis the German, Lothair, and Charles the Bald — were at war. Lothair had laid claim to the whole of Charlemagne’s empire after the death of their father, Louis the Pious, despite partitions and rebellions that been going on throughout the Empire. A civil war followed that lasted for three years until the Oaths of Strasbourg in 842 and, finally, the Treaty of Verdun in 843. The brothers Louis the German and Charles the Bald declared their allegiance to each other and rejected their brother’s claim to the imperial throne together in the Oaths of Strasbourg. The Oaths were recorded in Latin, Old French, and Old High German. In a show of solidarity to their respective kingdoms, Louis the German recited his allegiance in the Romance of his brother’s kingdom and Charles recited his in Francique, the Germanic language of Louis’ realm. This is the earliest evidence we have of a language that is distinctly French. In addition to being linguistically significant, the Oaths also marked the geographic division that created modern France and Germany. In 843 the official peace treaty called the Treaty of Verdun was signed, bringing an end to the civil war.

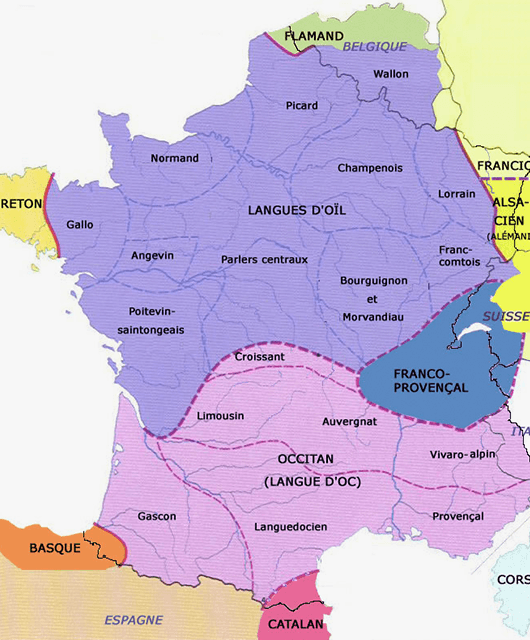

Where the langues d’oc and the langues d’oïl were spoken | Source: Guernsey Donkey

The development of the Old French used in the Oaths of Strasbourg continued in France and eventually broke off into two separate language families known as the langues d’oc and the langues d’oïl. The languages were named for the words they used to say “yes” — so the langues d’oc said “oc” and the langues d’oïl said “oïl.” Eventually, the langues d’oïl became more prominent, and the term for “yes” continued to develop phonetically to create the modern French word, “oui.”

However — before we get to modern French’s “oui” — French continued to spread throughout the Middle Ages due to the popularity of chivalric romances told by traveling troubadours. Troubadours were composers and performers who traveled and performed for noblemen and in courts around Europe. The tradition began during the 11th-century in Occitan, southern France — the region of the langues d’oc. Troubadours continued to rise in popularity and the majority of the famous troubadour poems come from the late 12th-century. The poems and songs focused mostly on courtly love and chivalry and were exclusively written in the vernacular as opposed to Classical Latin. Until this point in history, all serious literature, poetry, and religious texts had been written in Classical Latin. The focus on love and romance in these stories created an association between the language used and the content. The meaning of the word “romance” as we use it today comes from this period. The stories were written in a language that was colloquially known as “Romance,” so they became known as Romances — and because they were exclusively about love and adventure, the term “romance” began to refer to both the language and the subject matter. Thus, today we use the term “romance” when talking about Romance languages and about love.

Language is a way to share information with other people, and when many groups cohabitate they end up sharing words as a way to more effectively communicate with each other.

An illumination depicting the death of 12th-century troubadour Jaufre Rudel (noted for his love songs) in the arms of his lover, Countess Hodierna of Tripoli | Source: Wikimedia Commons

French’s connection to romance specifically came from this tradition, as the stories originated in the Old French-speaking regions and then spread to other parts of Europe. So the “Romance” language being referred to was actually Old French. Everywhere the troubadours traveled, people began to associate French with the stories of love and romance, and thus began the nickname the “language of love.”

Languages are powerful and dynamic tools of connection and culture. The traveling troubadours were exploring the creativity and playfulness of language in their stories of love and adventure. They were creating a linguistic identity and asserting their individuality as separate from the Classical elites. This phenomenon of identity creation through language continues in every generation with the invention of new slang terms and phrases. The constant changes that languages go through reflect the people speaking it at a certain moment in time. Language is the ultimate creative medium because it is universal.