SWEDIAN LIE

In this issue we talk to multimedia & projection designer Jared Mezzocchi about the use of multimedia technology — such as video & projection — in the theatre and its implications about our expectations on reality and storytelling.

Hi Jared, thanks for making the time to do this interview!

What drew you to projections design?

Jared Mezzocchi

It was a really happy accident! In college, I was acting & directing in theatre, and then writing & directing film and theatre as a double major. By the time I was in my junior year, I started tinkering with [multimedia] and got into Berkeley College for Interactive Media Arts. That got me jobs in New York at a club as well as with [performance company] Big Art Group, and I was hooked.

I really love theatre, and I love acting and directing, and I think as an actor I was lacking that feeling of authorship over the whole idea. Video — because of its sense of ‘live-ness’ — made me feel as though I can still pursue acting from a design standpoint, because I have to think about cues from a beat change, and I have to think about how to follow the actors and listen and respond to them. So I feel like in a way it bridged all of the needs that I think I’ve been seeking as a theater artist.

What do you think projections and video bring to the table that other design elements don’t?

Jared Mezzocchi

That’s a really good question. I think that’s the question of the century. I think if you can’t name something that explains [what] the other parts of the team doesn’t bring — or can’t bring — then you have found a spot on that show.

I used to think in the much broader stroke of, “I’m bringing this big idea to the table,” and I quickly found that video has a way of replacing, enhancing, or eliminating. Let’s say a telephone: you can replace a telephone by projecting a telephone instead of someone picking up a [real] telephone; you can enhance a telephone by having, when someone picks up a real telephone, a zap or marks around that telephone; or you can eliminate a telephone by projecting the Eiffel Tower onto the surface of the [real] telephone.

And so, with those three things in mind, I think that’s what you walk in [with] — what am I replacing, what am I enhancing, what am I eliminating? Is there a way in which this particular production can happen if the projectors were to blow a fuse one day? What would happen based on this idea? Could it happen?

I don’t think there’s an answer from the full [multimedia] community. I think this question has an answer from each specific show.

Working in this relatively new field/industry in the technical theatre world, do you find yourself constantly learning & discovering new techniques and tools as a professional designer?

Jared Mezzocchi

Oh, totally! There’s so much to learn. When I first started I thought I had learnt [all the] technical [aspects] — and I still do to a large extent, especially as the technology keeps evolving — but the more and more I’ve worked, the more and more I’ve realized it’s an evolution of communication and tactics; of how to use the tools that are in front of you.

Charlie Chaplin | Source: Glogster

Charlie Chaplin could do it, [communicate a story] with a pre-made video on film, and we have to remember that, just because every time we have new tools we think we’re closer to a sense of ‘live-ness’ onstage, that we’re no more closer than he was. It’s just that we have got a bit more accessibility now, with tons of tools.

I ebb and flow between getting caught up in the tools and in the looks, versus getting caught up in the moments and in the emotional journey of the piece. And I like that ebb and flow. I feel like I’m re-engaging with my fascination with math & technology, versus re-engaging with my fascination and love of the arts & the heart — being compelled by ‘moments.’ I’m constantly trying to figure out what is [the show’s] vocabulary, and I try really hard to get out of my head. I tell my students and I try to do this myself: just try to be as quick as possible, and get stuff up as quick as possible. Even if it’s not effective yet, it’s putting something out there to shape. Trust your gut and trust your instinct — and really improve upon your instinct, not your skill set.

Have you ever been in a situation where you thought video & projections were not the way to go in a project?

Jared Mezzocchi

I’ve said it a few times. Not a lot [though], because I’m really trying to see [opportunities]. We’re still in a new form and I want to push that limit [of what’s possible]. My impulse is to say, “What would be the ‘in’ for video?” It sometimes brings out a feeling of failure with a show [if the design and the show don’t work out well together], but I’m always glad I did it because I wouldn’t have said yes to that show if it was offered to me on Broadway, or in a larger scale. You have to celebrate the fact that theatre opens and closes [doors], and is an experimentation lab.

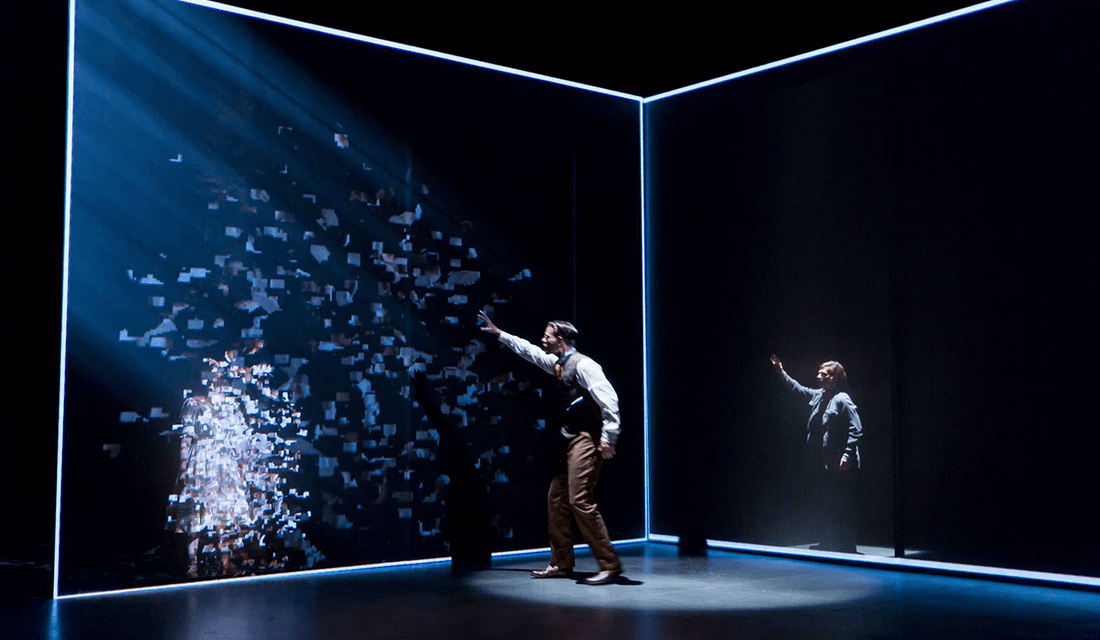

Let’s talk about one of the shows you designed for, where video & projections were integral elements — The Nether at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in Washington, D.C.

The Nether at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company | Source: © Jared Mezzocchi

A new virtual wonderland provides total sensory immersion. Just log in, choose an identity and indulge your every whim. But when a young detective uncovers a disturbing brand of entertainment, she triggers a dark battle over technology and human desire.

– Synopsis of The Nether

Can you talk a little bit about how you approached this show and its narrative as a multimedia designer?

Jared Mezzocchi

Artistically, it’s pretty fun, because we’re [essentially] designing rooms. So I started by doing what I usually do, which was showing the “wow” factor and saying, “Look, this thing can happen during this part,” and it quickly became apparent that Shana Cooper, the director, really wanted to make sure that the wallpaper looked correct and the rooms looked correct. That challenged me to think from an environment-to-effect, as opposed to effect-to-environment, design standpoint. [An effect-to-environment designer will think] “I want a ‘pow’ here, so what’s the rest of the space going to look like?” [On the other hand,] Shana said to me, “What is the space going to look like, and then I’m excited in tech to see what you can do to bring it alive.” So we were rendering out wallpaper after wallpaper to look at. That really changed my artistic palette, and I’m really appreciative of the amount of time we were in meetings. It was annoyingly frustrating to be in so many meetings, but then opening night happened and I just thought “This couldn’t have happened without so many meetings, and what a dream.” We ask for this [success] so often, and yet I think the freelance lifestyle makes it really challenging to actually breathe within that dream.

The Nether at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company | Source: © Jared Mezzocchi

I was really proud of it. It’s the first show that I think I can look at and say every cue mattered; every cue was effective for me, whether or not audiences picked up on all the effects. It was the first time I left opening [night] not seeking approval from the audience, and I felt really pleased by that — because it’s so frightening to be putting your stuff out in such bold ways. You can float or sink in those moments.

It must have been really difficult to coordinate between yourself and the other designers, given that the play’s narrative exists between two spaces: the real interrogation room and the virtual ‘Nether.’

Jared Mezzocchi

It really challenged me, and it really challenged Woolly [Mammoth]. There was a lot of anxiety around using that much technology. I was deeply involved with Sybil [Wickersheimer], the scenic designer and Colin [K. Bills], the lighting designer, but the thing I wasn’t ready for was flipping leadership from a design standpoint in terms of schematics — no one could move without me telling them how to move, and I was used to being the collaborator that goes, “Yeah, build me anything and I’ll bring it alive.” And they kept saying, “No, you have to tell us where your gear goes, and we’ll build it from there.” I wasn’t used to that and it was challenging.

That said, I’m really proud of it. It was really hard, and I think I’m still a little bit tired of it, but you know, doing one of these [multimedia-heavy shows] a year is really satisfying.

Did you and the other designers discuss the kind of future you envisioned would exist within the world of The Nether?

Jared Mezzocchi

Yes, we definitely did. We’re absolutely not The Matrix. We think the future is probably a world in which our senses are so diminished that technology is trying to bring us back to the real — and that’s where I started with the transitions, with the layering of light and patterns; we made sure all the wallpaper had a spackled look to it; we really tried [to be real].

We’re just so deficient in sensory experience that technology is trying to bring us back — which is anti-Matrix.

Was there anything you wanted to do with The Nether and you didn’t get a chance to?

Jared Mezzocchi

You know, I think there were a lot of ideas floating around, [such as] a live-feed component in the interrogation room that we swiftly cut when we realized that if we really wanted to make a harsh line between interrogation room and [the virtual world of] the Nether, [then we need to] take out the technology from the interrogation room so that we can really, truly be in a world [that’s different]. So no, actually. There was nothing that was cut that I was really disappointed with, and I’m proud of that.

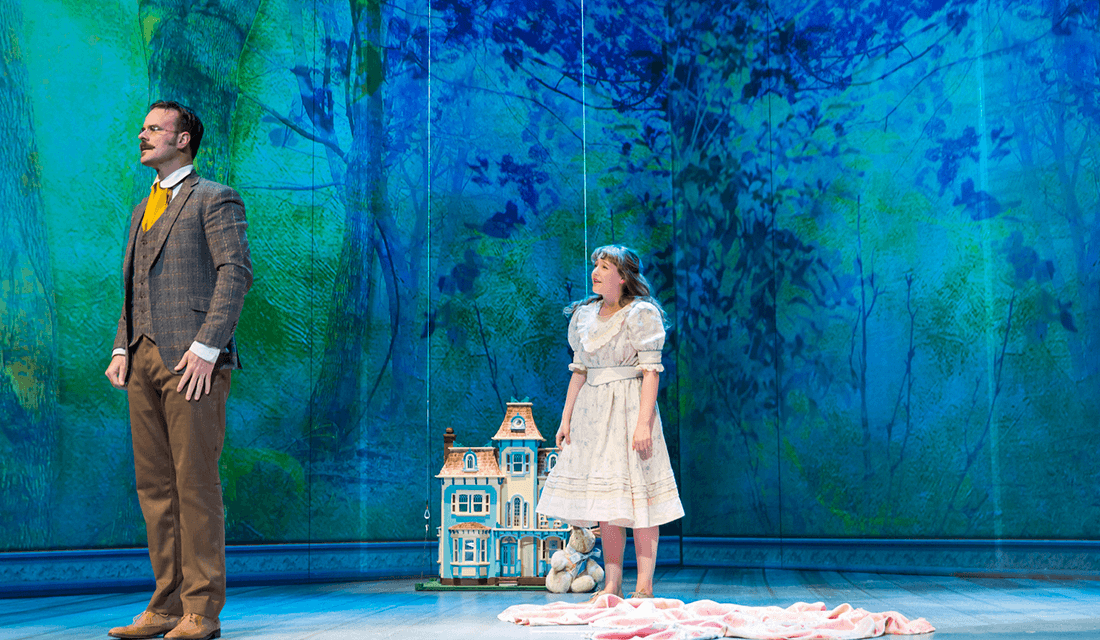

In addition to being a professional designer, you’re also the current Artistic Director at Andy’s Summer Playhouse, a children’s theatre company in Wilton, New Hampshire. You recently wrote, directed, and designed a play called Viewfinder, which had as one of its themes this relationship we have between the analogue and the digital.

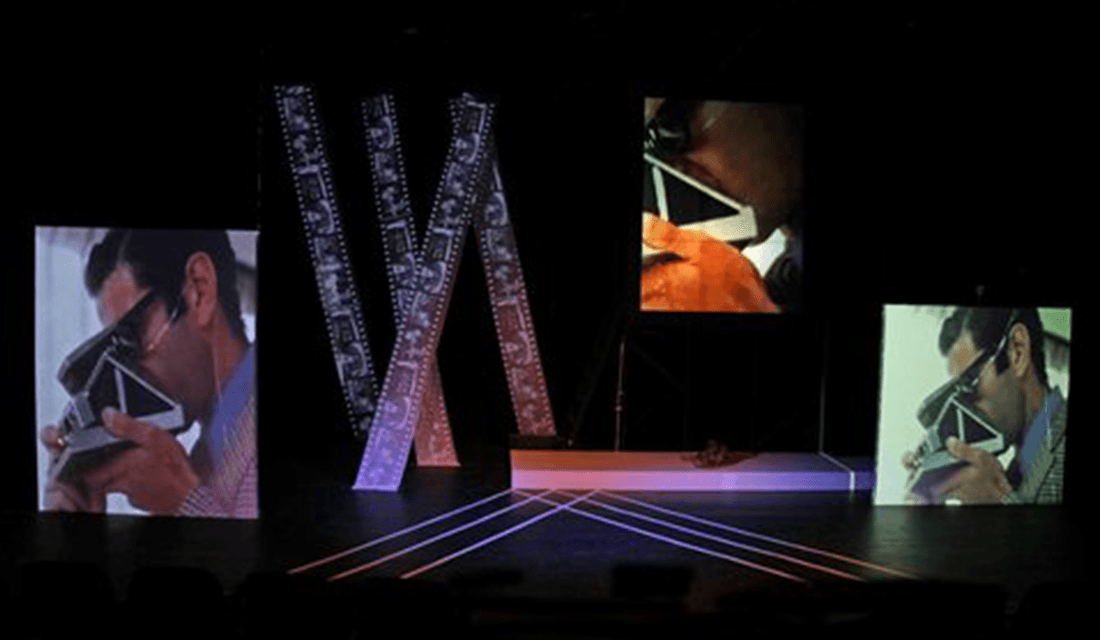

Viewfinder at Andy’s Summer Playhouse | Source: © Jared Mezzocchi

Our world is defined by the pictures we take, but at what point do pictures block us from the world we live in? In this multimedia tale of today’s need to document every moment with a finger tap, stop and join the journey of a roll of film, yes — an actual roll that takes time, yes — actual time — to develop. Follow its mission from Brooklyn to Paris searching for the owner, stopping groups of people along the way, and asking them to put down their phones, and dig deep into the identity of the now.

– Synopsis of Viewfinder

Can you talk a little bit about the vision you had for the use of technology in this play as a director, designer, and storyteller?

Jared Mezzocchi

Looking back, I think it was [about] using video in terms of heightening the impact of the memory of things. It was used in dreamscapes and in telling stories of the past, in a way that photography does [today]. Photography is the artifact of a former time that no longer exists. I was exploring the story in an ensemble-based method with the kids, and running through it I didn’t really touch video until the very end, even though in the script I wrote a lot of video into the story. I never paused the kids to say, “Now we’ll follow this [up] with video.” I wanted to make sure that without the video, we are [still] telling the story — but then the video enhances the dreamscape of [that story]. I used it in very particular moments and turned it off in other moments.

Viewfinder at Andy’s Summer Playhouse | Source: Jared Mezzocchi/Facebook

One of those particular moments was when we were trying to personify electronics. We had a live Spotify playlist projected onto the screen, but then had one kid holding a string with a clothespin on it that another kid moved from left to right — and that was the time code of the song; behind him was the Spotify projection. You know, trying to push things out so that you think, hey, by having these kids be a part of that [moment], it’s gonna have a greater impact when you’re thinking about Spotify later. Isn’t that what photography is suppose to do — to punch out a moment and make it more physically real for your memory? So we’re trying to do that the whole time [with video].

Do you think there’s a difference between designing for an adult audience versus a younger audience, especially in terms of their expectations with what’s possible on stage?

Jared Mezzocchi

I try not to have a bias between [designing for] age range, but I do utilize it. Children’s theatre is very whimsical and I really love that. I think it’s also [about the fact that] children would go anywhere. Children’s books & movies are more fantastical than anything else. The reason I’m drawn to directors like Michel Gondry or Tim Burton is because of precisely that: they’re bringing the fantastical and whimsical to [our] reality. Films like Big Fish or Edward Scissorhands — they’re placed in our reality, but pushed out just a little bit. I really dig that. And I think that’s where projections design really lives effectively, because you’re asked to do [shows] that are set in [a] reality that we as an audience are familiar with and not alienated from, and so I’m mostly trying to find my way into using projection as enhancement, to make reality breathe a little deeper.

Perhaps since we consume and experience reality at such an incredibly fast speed these days, your use of technology is to slow us back down to reality’s pace, even if it’s just for a moment.

Yeah, totally.

Given how commonplace video is in our daily lives — from television to film to our mobile phones — did you find audiences of any age range having different expectations about video on stage?

Jared Mezzocchi

I think they bring in the expectations of television and cinema, and I think it’s our duty as theatre artists to introduce a new way of using that technology. There’s a want for [Steven] Spielberg or The Lord of the Rings on stage, and if you try to that, you’re really screwing over the form of theatre. To ask everyone to eliminate the three-dimensional element and what’s happening in front of them for a huge effect on a back wall… That really destroys the essence of what theatre is. And so how do you do things on a back wall or pushed out on screens — or other surfaces or bodies on the foreground — to really make sure that we don’t lose track of the essence of theatre in that moment? Until we’ve established that vocabulary, I think that we’ll be fighting against cinema and television for a long time.

We’re talking about a 2-hour-with-intermission story and so, no, we can’t do crazy moving lines that are tracking actors when we’re talking about, say, online pedophilia [as was the story in The Nether]. After the first scene you’d be wowed by it, but then you’ll be really annoyed by it after because the actors have grown into something else — and the world isn’t defined by that [effect].

Last question: what’s your dream design as a theatre artist?

Jared Mezzocchi

I don’t really have one. Honestly, I’m never trying to get to the next project. I am loving the place that I’m at right now, where I’m getting all these scripts and they’re very pointed at projections, while others have no mention of it. I just hope I can continue broadening the vocabulary of the use of media. If anything, I think the dream is to not replicate myself over and over.

A couple of years ago, I felt that I did the same thing for every show, and I think that hurt [me]. So I made a goal for myself in the past year to really push and to make sure each show is a really different attempt at something [new]. That’s the dream: to make sure I’m not cornering myself into a kind of design. I think this year I did get there, and The Nether pushed me out of the corner in a really helpful way, so I’m really excited for the year [that’s] to come.

To me, I just want to make sure I’m a versatile designer, and I think that’s why I’ve put myself in this “teacher/children’s theatre/theatre professional designer” [nexus] because I think those three really can’t replicate each other, so through the form of [this intersection] I hope it shakes up my content. But I don’t really have a dream show. I just hope that when I’m walking into the space, people are excited about what I’m going to do next — and that, to me, is a good place to be.

Thank you so much for your time Jared, and good luck with your future projects!

Jared Mezzocchi:

He received his MFA in Performance and Interactive Media Arts at Brooklyn College. He is currently on faculty at University of Maryland, College Park, where he leads the projection design track in the MFA Design program. He is a resident artist at Woolly Mammoth Theater Company in D.C. and has directed and/or designed at theaters across the U.S. and in Europe including designing for Big Art Group and their productions of The People (San Francisco CA), The Sleep (Berlin, Germany, and NYC), Cityrama (Torino, Italy), SOS (NYC, Vienna Festival). He has worked for The Builders Association (Jet Lag), Rob Roth (Screen Test) and UTC #61 (Hiroshima: Crucible of Light, Velvet Oratorio, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep), 3Legged Dog (Downtown Loop); Jared has also worked at Arena Stage, Studio Theater, Theater J, Centerstage Baltimore, Olney Theater, Everyman Theater, Cleveland Playhouse, Milwaukee Rep, and The Wilma.

In 2012 he received the prestigious Princess Grace Award, the first projection designer to be honored with this national theater award. Mezzocchi grew up in Hollis, NH, where his mother still lives and where he will make his summer home as Producing Artistic Director of Andy’s Summer Playhouse. He has been a regular artist at Andy’s since 2009, directing such original productions as The Lost World, The BFG, The Block, and others. His production of The Lost World, written originally for Andy’s, won Best Original Play in the NHTA Awards and just received its D.C. premiere at University of Maryland in 2015.