JONAH CAMPBELL

The warm morning sun poured through the outstretched limbs of the Scots pines, the crisp ocean breeze tickling their needlelike leaves. The sprawling lawn from which the trees sprouted was looking more green than I could ever remember it, almost emerald in the bright sunshine. Slowly, I made my way across the hilltop to our meeting spot.

I was late this morning, though I promised that I wouldn’t be. But I was always late. He knew that. And I found him, just like the many times before, under the shade of one particularly gangly pine, peacefully awaiting my arrival, thoroughly unconcerned with my tardiness. I laid out the blanket I’d brought for the both of us, and gingerly lowered myself to the ground. I spread out the provisions I’d brought as my offering: A Baguette-Tradition, still warm from the ovens of the little Boulangerie, a small wheel of offensively strong Camembert — my favorite — and two large bottles of homemade apple cider — his favorite. To this day, like an old Polaroid, yellowed at the edges from the passing of years, I can still see his face the first time he tasted apple cider…

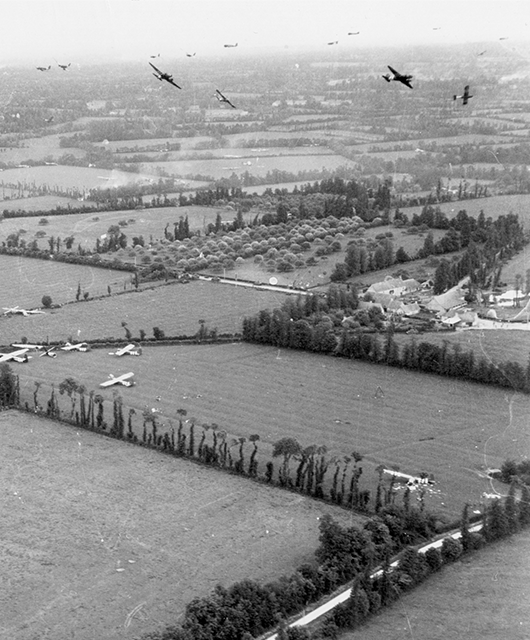

Douglas C-47’s over Normandy’s Cotentin Peninsula | Source: National Museum of the U.S. Air Force/Wikipedia

We stood side by side, both peering over the shoulders of the men in front of us, out through the open cargo hold into the purple-black night below. The night sky seemed unimaginably dark from above. I had never asked him if he was nervous in that moment, standing there staring into that faceless fate, but if he had felt anything like I did, he was terrified. The roar of the American C-47’s engines and the swirling wind did little to drown out the thoughts now pounding in my head. We were just kids for Christ’s sake. And yet here we stood, tasked with spearheading one of the most critical maneuvers in the symphony of Allied war to-date. We had practiced this very night thousands of times, but standing there in that moment, I felt as if it were for the first time. The gravity, the finality of it all, was sinking deep into my chest, constricting my lungs and causing my heart to beat through my neck. I was acutely aware of the weight of the canvas pack on my shoulders, a heavy reminder that the only thing standing between me and eternity was the silk packed tightly within, ready to spring forth at the tug of a cord. Hopefully. The yell of our commander severed my far-off stare, bringing perspective, and reality, rushing back to a pulsating myopia of the five feet between me and what destiny lie ahead.

“GENTLEMEN, AT THE READY.”

With the blood in my ears rising to a boil, I never heard the “GO, GO, GO,” as my body moved before I was able to process the words. With one glance to my side, I watched as both of our pairs of boots disengaged from the safety of solid, corrugated metal, and felt my stomach leap into my throat, as I turned towards the darkness, to watch the earth race up to greet us.

The jump had gone well, technically speaking. The chutes had deployed, and the landing was soft, but we had been blown off-course by nearly two miles, our ten-man unit forced to reassemble and navigate the farmland of Normandy under the gaze of the full moon to make our original mark. For six days, we had fought along the coast. The scrums were white-hot, and we lost two men to the flaming crucible in that time. Though, with morbid optimism, I knew that two men was an absolution of war by comparison. On the 6th day of the offensive we finally secured the coastline and began pushing southward, towards the town of Carentan.

Here we would stay for another three weeks.

We arrived early in the morning, the first rays of dawn cleaving the fog that had been draped over us in the night. We were wearied, battered, and stunned. Sound and sight were a muted hum of white-noise and static. The town itself was veiled in greyscale. It was easy to imagine another time, when the low-rise stone buildings, all arranged in trim lines along the winding cobblestone streets, were bursting with vibrant hues, alive with merchants and residents dancing the “Waltz of Life.” However, now, those same buildings stood gaunt, drained and weeping under the oppression of war. Vast fields of abandoned, achromatic farmland surrounded the town, dotted with farmhouses and stables — most but empty shells, left behind to survive or perish at the mercy of chance. Most.

We picked a small, grey-stone farmhouse a mile from the town center for a place to stop. We passed through its upturned wooden gates, crossed its little cobbled courtyard, and came to rest on the steps of the entryway, happy to find a brief moment of nirvana in the sweet release of idleness. The birds announced the new day’s arrival as we sat, their songs a pleasant escape from the discordant ringing in my ears. As I listened, one birdsong in particular caught my attention. This one carried differently from the others. It was slower, and conceivably clumsier. I followed the sound with my eyes, tracing its path on the wind, and felt the last beat of my heart chocked off in a gasp, as I found my stare returned. I was paralyzed, frozen in space, as my eyes were met by the eyes… of a child. Across the courtyard, a little head of tousled brunette hair, and a pair of inquisitive eyes, poked out from behind the wooden pane of a small window on the broad side of the stables. From over the boy’s shoulder, an older man leaned out of the opening and quietly, sincerely motioned for me, and the others, to enter.

The last of our group filed into the musty warmth of the stables, the disturbed dust and hay clung to the beams of sunlight that streamed through the open barn door, bathing the space in a caramel haze. The man with the silver beard, who had motioned from the window, appeared as if from nowhere, and offered a curt but benevolent “Suivez-moi.” We found ourselves following this man through the shadows, up a flight of creaking wooden stairs, and into a cavernous atrium in the barn’s attic. The morning sunlit chamber was clearly being used as a residence, with makeshift beds crowding one corner, and stashes of food and equipment neatly organized along the walls. We were greeted by two young children: the boy from the window, smiling and exclaiming in accelerated French, evidently delighted to be meeting soldiers of war, and a young girl with short, auburn pigtails, who remained cautious, offering a gentle smile and moving quickly to the side of a middle-aged woman with coffee-brown eyes, who shook each of our hands with an angelic “Merci.”

We communicated as well as we could, reenacting our journey through a mélange of poorly performed charades. We explained who we were: American paratroopers fighting the Germans to save the world. One thing we were not was humble, even when we lacked the proper vocabulary. And from the fresh vegetables set in our laps, we gathered that they were farmers — a father and mother to the two children, who had chosen to stay and tend the crops, and prepare for the Autumn harvest of apples.

Apple trees spanned the length of their estate, and every Fall they spent countless hours collecting the fruit, to be turned into drink. And though he spoke to the group in his native French tongue, the father’s passion could never be misinterpreted. He was a farmer by trade, but a cider maker by devotion.

He addressed the group with a twinkle in his eye, hinting at some knowledge we would soon all be privy to, and with a few choice words, rose swiftly to pad over to a large mahogany chest sitting in the far corner of the room. He knelt and flipped its heavy iron latch, the lid protesting as he hoisted it open. From the belly of the chest, he pulled a bottle and returned to the group. He sat cross legged and presented his treasure for all to see. It was green glass, shaped much like a wine bottle, with a cork, and an elongated neck, but the front panel revealed a golden, hand-stenciled apple tree, with sagging branches, heavy with fruit. He gripped the neck and removed the cork. The smell of its contents billowed out, saturating the air in an instant: baked, golden apples freshly sliced, with whispers of cinnamon and maple syrup, combated by a fresh, sharp acidity that puckered the nostrils. My mouth watered. He passed the bottle to his left. “Boire.” Taking it in his hands, and raising the bottle’s open mouth to his own, I watched the amber liquid pour past his lips. He lowered the bottle and with it, his head, as his eyebrows rose into the atmosphere. His stare leapt miles into the distance, while he struggled to comprehend this unfamiliar, visceral mouthfeel. His words caught, able only to express emotions through sound. “Wh…. Ha….” The look of utter confusion he shot the farmer reduced the entire room to tears. It was a happy moment. One I would remind him of, as I knelt by his side, applying pressure, my hands glistening in crimson…

BUZZ-BUZZ. BUZZ-BUZZ.

The colors of the past dissipated back into the emerald lawn stretching before me, as the phone vibrating in my jacket pocket shook me from the memory. I looked down to see my granddaughter’s number flashing across the screen. I had lost track of time. I was late for breakfast, again. I gathered my things, rolling up the blanket and packing the last of the food, leaving the bottles of cider for him. I apologized for having to leave on such short notice. He understood. I promised I would return, as I had every year, for the last 70 years. And then I slowly rose from that shadowed spot beneath the pine, and began the long walk back across the hill, looking over my shoulder for one last moment, to watch his gravestone, flanked by green bottles of apple cider, disappear behind the thousands of others, all end-dated with year, 1945.