CALEB LEWIS

It’s All Downhill From Here

Simone Biles was glorious! Wasn’t she? Really think back to it. And if you weren’t watching her in the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, then I beg you on my hands and knees to go back and watch the highlights. My god. Remember the way she flew? Really flew. She would lift up off of the ground and you would wonder if she was ever going to land. It was as if at any moment she could decide to just keep rising and soar into myth, finding a home among the gods on Mount Olympus. It was impossible to watch her without feeling something… big. Selah. But she did come down, as all humans must. And while she always landed on her feet — reaching the top of the podium four times in Rio — she still fell into the real world that holds this one truth: all things come to an end. She didn’t cease to exist after the Games in 2016, we just stopped thinking about her.

Why Is Simone Biles the World’s Best Gymnast? | Rio Olympics 2016 | The New York Times | Source: © The New York Times/YouTube

Olympic Athletes. Wow. Those two words conjure up the image of a glorious person. The paragon of humanity. Proof of what can happen if you put your mind and body wholly into something. Look at what we can do. Just look at it. Wonder at it. But behind this wonder of the world, this Olympic athlete, is a human being. A human that lives on after we’re done with them, after they’ve fulfilled their function as our representative on the world stage, after they’ve failed or triumphed. Life goes on, as they say. Though in the grand scheme of things, the Olympic Athlete’s life has really only just begun.

No Such Thing as Forever Young

The average age of Olympic athletes for the 2012 Olympics in London was around 26, meaning that half of the attending athletes were younger than 26 years old. At the most recent Olympics in Rio, the youngest athlete was swimmer Gaurika Singh of Nepal at 13 years old. Most of the older athletes come from sports that rely less on raw physical ability of the athlete, such as equestrian, where the oldest Rio Olympian, Julie Brougham, competed at age 62. Others from the older contingent in more physical sports have been able to lengthen their careers with the advancement of sport medicine, though here “older” really means around the age of 30. Regardless of the length of their careers, many Olympic athletes began their training in their youth, with some gymnasts starting before the age of 10, with serious competition occurring in their teens. Usain Bolt, who turned 30 on the final day of the 2016 Olympics in Rio, was only 21 when he first broke the record for the 100m. Simone Biles, the star of the Rio Olympics, was only 19 when she set the record for most gold medals won by a female American gymnast in a single Games.

Gaurika Singh Wins 100m Backstroke at the 2016 Olympic Games | Source: Kamal Aryal/YouTube

Sport in general is a game for the young. It’s a celebration of what the human body is capable of. The problem is that the human body has an expiration date, though many of its systems cease to function as highly as they used to long before that date is reached. This leaves the young to be the bearers of the glory of athletics. Their bodies can recover faster and have a natural flexibility. And as they age into their young 20s, they only get stronger, faster, and more knowledgeable. No wonder peak general athletic age is 25 to 27 years old. But this focus on athletic development while young has its dark side — which makes one wonder, are we sacrificing our youth in the name of sport?

All That Glitters Is Not Gold

Is this worth the price we ask our young athletes to pay?

There’s a phenomenon known as the “Olympic blues.” The idea is that the Olympic Games is a period of heightened reality for the athlete: they’re under the highest pressure, they compete often, they have the greatest triumphs or the most tragic defeats, the focus of the world is on them, and they’ve been training all their lives for this moment. And then it’s done. Just over. What does one do after the defining moment of their lives? Most fall into a depression. Many attribute the immediate depression to the exhaustion of the experience, physically, mentally, and emotionally, the come-down from the high of the games. It’s natural to need time to recover from one of the most overwhelming experiences one can imagine. This prolonged depression comes from the loss of identity. These athletes have been training and competing for most of their young lives; they identify as a swimmer, a gymnast, a wrestler, etc. After competing on the largest possible stage, there is nowhere else to go. They’ll never experience anything close to competing at the Olympics, unless they go again. This loss of identity is even greater if they’ve decided to retire. They don’t know who they are outside of the sport. Female Olympic gymnasts generally retire in their early twenties. Imagine thinking your life is over at 22.

We recognize [young athletes] as the best we have to offer. We do this without thinking of the consequences for the rest of their lives.

Right now, the average life expectancy in the U.S. is 78.6 years. That’s about 56 years left of her life that she doesn’t know what to do with. And she is faced with the prospect of living it knowing that nothing will be like the experience of going to the Olympics. Life will never hold as much, well, life as when she competed at the most important sporting competition on the face of the Earth.

It’s tempting to think that depression only strikes those who fail to get a medal at the Olympics, but it’s far from the case. A notorious example is Allison Schmitt, a freestyle swimmer who had about as much success as possible at the 2012 games in London: she broke a world record and won 5 medals, three of them gold. Her success didn’t exclude her from facing depression, nor did it bypass 23-time gold medalist Michael Phelps, who also found himself struggling with depression in the wake of the 2012 Games in London. In fact, Schmitt and Phelps would lean on each other as they looked to recover from their depression, talking things out in the car rides home from practice and realizing that they weren’t alone. And that’s the key: too often athletes find themselves in seclusion because of their lifestyles, when what they really need during these times of hardship and illness is a support network of friends and family. Sometimes you can’t make it on your own.

Olympians Michael Phelps and Allison Schmitt: Thoughts on Depression and Mental Health | Source: Helga Luest/YouTube

Mind Games

Athletes don’t just have to train their bodies to compete, but also their minds. They face unique stressors, which can lead to high levels of anxiety. And where would the pressure be any higher for an athlete than at the Olympics? Athletes find many ways to cope with the stress and anxiety, including pre-game rituals and other idiosyncrasies, such as Michael Phelps’ death stare. But these coping mechanisms don’t always succeed, which can negatively affect the athlete’s performance. We have a tendency to underestimate just how important the mental game is in sports. With elite athletes, very little separates them physically from one another, leaving the mental game as an important factor in performance. Athletes must stay focused on the task at hand, their minds can’t be distracted.

Mikaela Shiffrin: The making of an Olympic champion | Source: © 60 Minutes/YouTube

Mikaela Shiffrin has been dominating the slalom for years, she won gold at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, becoming the youngest Olympic slalom champion at 18 years of age. But in the lead up to the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, she’s begun to experience high levels of anxiety. This has caused her performance to slip in competitions just before the beginning of the Games, taking home second or fifth where normally she’d have a comfortable lead at the top. Athletic anxiety can come from many different sources and can strike at any moments. For instance, some point to Mowrer’s Two Factor Theory of Avoidance (first formulated by American psychologist Orval Hobart Mowrer), arguing that an athlete can begin to associate their sport with a bad experience, such as a bad injury or accident or even just a terrible performance. This causes her to begin to fear specific moments in her sport, or even the sport itself. When the athlete finds a way to avoid that moment, such as taking a turn at high speed, this brings feelings of relief, further reinforcing their anxiety and negatively affecting their performance. Another source for anxiety are high levels of intense scrutiny or a feeling that more people are watching her performance than ever. Mikaela identifies what might be her earliest experience of anxiety at the FIS World Cup in Killington, Vermont in 2016. The world, and her 95-year-old grandmother, had their eyes glued on Shiffrin, expecting her to dominate in her home turf. It didn’t turn out as expected. She came in fifth in the giant slalom, and though she won the slalom, it wasn’t with the domination she deeply desired.

More and more, athletes and sports organizations are recognizing the importance of sports psychology, with many nations now employing whole teams of sports psychologists to get their athletes to the Olympics. However, most sports psychology is focused merely on the performance of the athlete — ways to make them perform better. This leaves them open to any form of mental issues that doesn’t directly affect their performance. It can leave their anxiety unresolved in non-sports situations and leave them at risk of depression.

[This] focus on athletic development while young has its dark side — which makes one wonder, are we sacrificing our youth in the name of sport?

A Whole New World

Athletes face the future lacking the tools to find immediate success. Sure, they have the drive, the team spirit, tenacity, and adaptability that many job industries love. But there is more to life than that. Olympic athletes spend hours upon hours upon hours training for their sport. Michael Phelps was known to spend six hours in the pool every day. And that’s just the time spent training, not including getting the right amount of rest, eating the correct foods, and everything else that goes into being an elite athlete. That’s a life spent focused on their sport, in an environment unlike most of ours. They’re used to consistent feedback, they’ve learned to socialize only with others involved in their sport, and they haven’t reached out into other areas to claim an identity. So here they are, with these learned traits that hinder them in this world, and yet there’s one more trait that makes it even harder to succeed: a reluctance to ask for help. Allison Schmitt has this to say:

“We’re taught we can push through anything, we can make it wherever we want to go, and we’re always told to not ask for help. At the end of the race, we’re not having our coach finish for us, anyone finish for us.”

These athletes have been rewarded for being independent, for being strong, and for being able to rely solely on themselves. We’ve taught them this and then set them up for a world where needing help is the status quo. Moreover, after finding success as a great athlete, it’s difficult for them to struggle or to not have immediate and overwhelming success in something. This leaves them ill-suited to navigate a world the rest of us grew up in. A world where we have to figure out for ourselves if we’re doing right with little feedback. Where we struggle to have a social life with people who couldn’t be more dissimilar from each other. Where we all have a variety of interests and life goals. Where we have to learn to ask for a helping hand to get by.

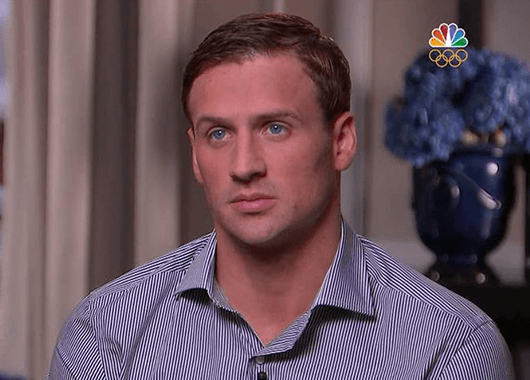

Ryan Lochte’s tell-all TODAY Show Interview | Source: © NBC

Look at the Ryan Lochte incident in Rio de Janeiro, where he and three other swimmers claimed they had been robbed at gunpoint when, in fact, they had vandalized a gas station bathroom while intoxicated and found themselves confronted by armed guards. This is not how normal people act. Sure, I would bet that most of it has to do with being a high-achieving white male and the privilege that comes with that. But I would also bet that it has to do with spending most of your time in a pool, either by yourself or with other white males. Either way, it’s connected to his time secluded from the rest of the world as he focused on his training. In his experience it’s okay to act this way because he doesn’t know how average people behave. This is an extreme example, I know. But the sort of drive, aggression, and self-focus that sport encourages affects how athletes are socialized, and these traits aren’t always appropriate in many arenas of life.

Running on Empty

The harsh truth is that many Olympic athletes are below the poverty line even before they retire. Getting sponsorships is the exception, not the rule. Most U.S. Olympic athletes can look to receive a stipend between $1,000 and $2,000 per month. Winning gold makes it a little better, but not a lot, receiving $50,000 per year. Sure, you can also get bonuses for winning medals: bronze gets $10,000, silver gets $15,000, and gold gets a whopping $25,000, and all this pre-tax! These athletes sure are living large! And I’ll repeat that this is how they live before retiring. Upon retiring, not only do they lack the skills and prospects that lend to success, but they’re starting at a place of disadvantage. Furthermore, even those athletes that have sponsorships face losing them after retirement. While they start off in a better position, they too find themselves with few options to live a sustainable life. Tonya Harding may be the most infamous Olympic athlete of all time, but her post-Olympic career of bouncing from project to project is about par for the course: she managed a pro-wrestling team in Mexico, started a band, tried film, became a boxer, and even was a guest commentator for truTV Presents: World’s Dumbest, among many other miscellaneous jobs. Mark Spitz, a swimmer who won 7 gold medals at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, has a similarly eclectic CV after retiring at 22: he tried dental school, acting, real estate, and even a competitive Olympic comeback.

These athletes spend a lifetime wondering, “What’s next?”

After competing on the largest possible stage, there is nowhere else to go.

The Only Thing Necessary for the Triumph of Evil

Larry Nassar and his crimes aren’t as rare in Olympic sports as we’d like them to be. There are others like him. Olympic athletes may be incredibly daring and strong in competition, but they are also among the most vulnerable. Their success and drive have lead them to being surrounded by more people, by more power, and by more uncertainty. An Australian study on the prevalence of sexual abuse in sport found that, of the athletes in the study, 31 percent of the females and 21 percent of the males reported experiencing sexual abuse before the age of 18.

Larry Nassar sentenced: I signed your death warrant, judge says | Source: © CNN

Athletes are surrounded by people they trust. People that they are taught to obey. People they are taught have their best interests at heart. People that have the authority to punish and reward them. Remember how we discussed how athletes are isolated in training, taught to be strong, and learn to rely on themselves to fix problems? Those same characteristics assist in making them vulnerable to assault and keep them from stepping forward. The athletic system is built to give authority to the sports personnel around the athlete. They’re the gatekeepers to competition, the ones athletes need approval from. Athletes are taught that if they want to compete higher, get back to competition sooner, or even compete at all, then they have to do what the coach/doctor/trainer/nutritionist says. Experiencing sexual abuse is life changing and can lead to physical and mental health issues, including depression, drug abuse, and suicide, among many more. In the case of Larry Nassar, he saw these young women at their most vulnerable. When they were injured or needed medical advice. At a time where they needed his help to follow their dreams. And he took advantage of them, for decades. More than 160 women have come forward, bringing to light the crimes of Larry Nassar, among them are Aly Raisman, Gabby Douglas, McKayla Maroney, and, yes, Simone Biles.

Don’t You See the Family Resemblance? That’s My Brother

We encourage young athletes to sacrifice so much: their youth, their health, their financial stability, and so much more. We promise them fame, maybe wealth, in order to be our standard bearers. We recognize them as the best we have to offer. We do this without thinking of the consequences for the rest of their lives. They are left on their own to deal with the consequences of giving away their formative years. The years that many of us find our lifelong friends, that we discover the most about life, where we learn to make mistakes and fail. We sacrifice young athletes on the altar of sport, and we think nothing of them after. After they have lost their use, they mean nothing to us. Except memories.

Here’s the thing, I’m sandbagging a little bit, but it’s because I’m trying to make a point by using sport for something it’s great at: being a symbol for our everyday lives. At some point in our lives every single one of us will be faced with the questions “What’s next?” and “Who am I?” For many, this can be right after graduating from high school or college, but it can come much later, maybe after losing a job, or going through a divorce. We each face these moments that challenge our concept of who we are and where we are going. Our society as a whole has a problem with equating our profession with our value in this world, even though there’s more to life than earning a paycheck. It behooves us to find multiple points of identification, whether it’s in our communities, our families, or our hobbies. And maybe most importantly, we should remember that depression and other mental health illnesses can affect anybody at any time, even Olympic gold medalists. Our major lesson from Olympic athletes is that we need to learn to look out for each other and be kind to ourselves. It’s a hard world out there and we should be working for the betterment of everyone. Olympic Athletes. They really do inspire us to be our best selves.