DONOVAN OLSEN

Imagine you walk into a museum or an art gallery or even a theater. You might have an approximate idea of what to expect. There will be finished works, they will likely be stationary or at least confined to a particular part of the space (ie. a stage), and there are often unspoken expectations that you will speak in hushed tones, or not at all, and that you will not touch anything, ultimately leaving the space exactly as you find it. These expectations originated to create order, restrict access, and Other those who might break the rules.

Now imagine you walk into a lobby, or a warehouse, a church basement, a backyard, or your next door neighbor’s house. This event has been advertised as an art show, or maybe even as a play, but many of these aforementioned expectations have been turned on their heads. This space is not a hallowed institution. There is no clear distinction as to who is a performer or creator and who is an audience member. Everyone seems to be talking, maybe even loudly, and participating in a myriad of activities. This art is too alive, too present-tense, for passive decorum: instead, the expectation is to play. You realize that this particular artwork is still in creation, and that it will necessitate your personal, social engagement.

Three Personal Definitions

Socially engaged art (SEA): abbreviated as SEA, an art form in which the content emerges from community-based collaborations, is created for a particular audience, and acts with the aim to improve social conditions. Socially engaged art is a practice which challenges dominant forms of knowing, encourages a shift in creative power, and often relies on active audience participation to be created. Socially engaged art seeks to disrupt norms of both creation and consumption.

Play: commonly defined as a pure state or an activity rooted in enjoyment rather than expectations or rules, or as in the prologue to Stephen Nachmanovitch’s Free Play, it “may be the simplest thing there is — spontaneous, childish, disarming. But as we grow and experience the complexities of life, it may also be the most difficult and hard-won achievement imaginable, and its coming to fruition is a kind of homecoming to our true selves.”

Myself: I am a white, non-binary trans director, deviser, writer, performer, and socially engaged artist: I make art from a number of intersections of these roles, and I bring play with me wherever I can. I place high values on bravery, safety, playfulness, collaboration, and dignity. Furthermore, I deeply advocate for lightness, levity, and joy as essential tools when creating theatre, especially around heavy topics.

Examination #1: La Casa, Casa en Común Collective

While socially engaged art is intended to be community-oriented and aims to be accessible, it is often housed within specific companies and collectives. Two (of many) notable companies active today are the Sojourn Theatre and Cornerstone Theatre Company, both of which specialize in producing art in conversation with communities. And while they produce work in the form of plays, this is not the only approach to socially engaged theatre.

A Glimpse into Cornerstone’s Impact on Communities | Source: CornerstoneTheatre/YouTube

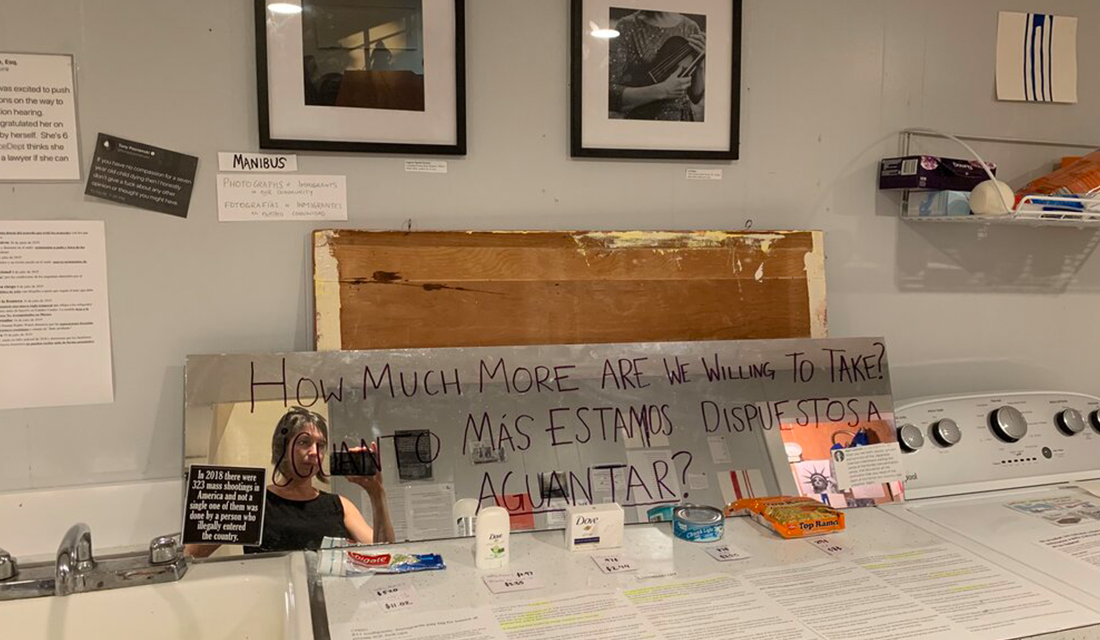

Cooking in a kitchen, salsa dancing in a dining room, writing down fears and burning them in a backyard, conversations in one bedroom, and art installations in another. Our first example is La Casa: a devised, immersive, and interactive theatrical experience created in Walla Walla, Washington in the summer of 2019 by the Casa en Común Collective. It was created, rehearsed, and performed in the house I lived in, which was open all summer to collective work, and later to audiences for a designated weekend of synchronous, exhibit-style performances.

La Casa was built from a series of conversations, both within the collective and in each collaborator’s personal relationships. These conversations later gave rise to theatrical moments within the show as well as questions we would pose to our audiences. Both the collective and the show were organized and designed to encourage conversations about immigration, framed within experiences of home and community. We had a wide circle of firsthand collaborators: at our first collective meeting, we had twenty-plus people present, some of whom ultimately did not continue with the project, but who generated and inspired ideas and concepts that carried us through and informed how we conducted dialogue, structured activities, and reached out into our communities. Other collaborators participated in a number of ways without ultimately performing in the piece and some, of course, stayed onboard from the first meeting to the final performance.

Photos courtesy of the author

After childhood, we are not, broadly speaking, expected to remember how to play and it requires an amount of unlearning (of shame, of inhibition, etc.) to do freely — and if we are able to unlearn these restrictions and culturally imbued expectations, what else do we have the capacity to unlearn?

You realize that this particular artwork is still in creation, and that it will necessitate your personal, social engagement.

In this project, play took the form of exploration. As a collective, we played with transforming a house into a theatre-space, and invited both our collaborators and our audiences to experience a familiar type of space — a lived-in home — in an unfamiliar way. We, as facilitators served food to visitors, built temporary art with found objects together, facilitated conversations, and invited responses to a number of prompts through both individual and interactive methods. By encouraging play, and welcoming audiences to explore an active, living, breathing home where moments of performance lived alongside moments of direct engagement and ordinary interaction, everyone who entered and was willing to follow our shape and model became empowered as a co-contributor.

Photo courtesy of the author

Socially Engaged Art Insight #1: Participation

Socially engaged artist Pablo Helguera presents four models of audience participation (nominal, directed, creative, and collaborative) with the caveats that all models are non-hierarchical, can enable success in different ways, and may be simultaneously encouraged in a single project in varying combinations.

Try combinatory play with books. | Pablo Helguera | The Art Assignment | Source: © The Art Assignment/YouTube

The two forms of single instance participation are nominal participation (reflective, passive) and directed participation (ie. visitor completes a specific task). In nominal participation, an audience member might simply sit/stand/walk and view the work in person, but they do not take any direct action within the structure of the work. In directed participation, an audience might engage with a clearly outlined task: writing a response to a question, learning a dance step, discussing a prompt with someone near them.

Next, there are the two forms of longer form participation over time, which are creative participation (offering content for a component of a work) and collaborative participation (sharing responsibility for structure/content development). In creative participation, a visitor (likely a repeated visitor) might share in conversations about the work in its planning stages, or participate in an interview or dialogue which later informs the final work. Finally, in collaborative participation, one will often act as a regular participant in the creation of the work as a planner, organizer, co-creator, player, guide, documentarian, teacher, peer, or any overlapping cross-section of these. Socially engaged art is not intended for passive consumption, but for active participation and/or co-authorship.

Recommended read: Education for Socially Engaged Art by Pablo Helguera

Examination #2: Teeter-Totter Wall, Rael-San Fratello

Play itself can disrupt norms and act as a form of protest. For forty minutes on July 28, 2019, three hot-pink steel seesaws sat balanced within the gaps of the U.S.-Mexico border wall. An architectural work conceived by the firm Rael-San Fratello, implemented in collaboration with Colectivo Chopeke, a social design group in Juárez, and constructed by Taller Herreria.

Transforming the Border Wall into a Teeter-Totter | Rael San Fratello | ARTIST STORIES | Source: © The Museum of Modern Art/YouTube

Generations of community members from Sunland Park, New Mexico and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua engaged in pure, childlike play — under the watch of border patrol agents — enacting and embodying the co-creation and co-authorship tenet of socially engaged art. The presence of see-saws at a site of conflict is not, in itself, especially meaningful or resistant. Children engaging in otherwise normal play at a site of division, policing, and surveillance is a different story.

See-saws operate through balance and leverage. The act of playing on a seesaw is imbued with counterbalance, interdependence, and cooperation. We teach children how to interact with the world through play, among other things. In asking multi-generational communities to play and follow the lead of children, adults are required to unlearn their inhibitions and to question the broadly-accepted constructs (ie. of safety and division) surrounding sites of conflict.

This art is too alive, too present-tense, for passive decorum: instead, the expectation is to play.

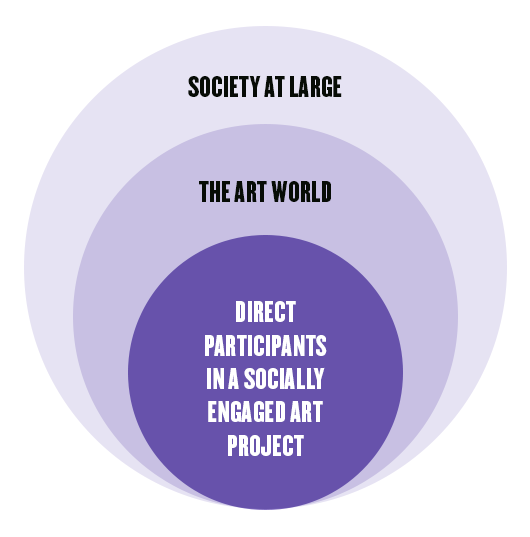

Within the socially engaged art model of viewership and co-authorship, the first circle of engagement is made up of those who are directly bearing witness to the process itself: the co-creators. The secondary circle is then understood as those who would critically engage with the work from a distance without actively participating, and the tertiary circle of viewership is thought of as those who hear of the work through another source, such as an art or news publication. Put another way, the circles could be visualized like the following.

Usually, when creating socially-engaged art, co-creators adjust and define each of these categories to specifically reflect their own community, and their understanding of how word of the piece may travel. It is noteworthy, then, that the circles of audiences for the Teeter-Totter Wall fit the above model near-perfectly, since socially engaged or public art doesn’t always garner national attention in the way the Teeter-Totter Wall did. Since the Teeter-Totter Wall was constructed in a site already rich with conflict, debate, and political tension, an act of joyful resistance skyrocketed just shortly after the temporary playground was dismantled. And so it was witnessed by those directly present, engaged with and analyzed by public art circles (including as the cover story of the 2020 Public Art Review), and became national news, reaching those otherwise unfamiliar with socially engaged art.

Some socially engaged art makes space for the literal play of childhood — Teeter-Totter Wall and the Contrafilé Group’s The Children’s Rebellion. Demanding space for joy where it has been denied (in youth detention centers or at a heavily patrolled border wall), where freedom is policed and actions are surveilled radicalizes this play, and makes it a form of protest.

As the formative architect of the project, Ronald Rael said, in an interview with PBS NewsHour:

“The work is an act of protest, but we were not out there with picket signs. We were not out there stating particular messages of resistance. We were demonstrating how the act of play, the act of engaging that place, was our act of resistance to say that, ‘This is our place,’ and we can dismantle the meaning of the wall and its violence.”

Socially Engaged Art Insight #2: Risk and Caution

The stakes of socially engaged art are high, and the margin for error relatively low. My teacher, Tia Kramer, put it approximately this way: while in other art forms, you are encouraged to try and fail repeatedly, in socially engaged art you cannot fail because you are dealing in other people’s lives, stories, and time.

Socially engaged artists must act with caution, and prioritize collaborators’ agency over their individual creative practice(s). Relationships and conversations are everything. There should be a constant line of questioning as to the goals, hopes, and dreams but also responsibility and the potential for harm. A socially engaged artist should understand to whom they, and their art, are responsible, and keep that at the forefront to the best of their ability.

Art for or about a community must be made by or alongside that community: this allows for genuine process and transformation.

However, a determination not to fail can inject varying amounts of pressure and tension into a practice. This necessitates balance. Levity and playfulness, where appropriate, can make space to be fully present with your collaborators and with the issue(s), through mind and body alike. In her book, noted choreographer Deborah Hay expands on the relationship her body, as a dancer, has to games and play.

“Every cell in my body has the potential to perceive Now is Here. Now is personal. Now is past, present, and future acknowledged together as it unfolds each moment. Here is locating my changing presence in the space where I am dancing, including my relationship to the audience.”

– Deborah Hay, My Body, the Buddhist, 2000

Playfulness and full-body presence can be transformative, particularly in an art form which traverses many relationships to an audience.

Examination #3: State of Incarceration, Los Angeles Poverty Department

As has been established here already, play can be crucial when reckoning with difficult and/or personal themes and content. Play allows for both mindfulness and radical joy. Theatre gains its power from its ability to provide and inspire catharsis. In a straight play (or non-socially-engaged work, for our purposes here), catharsis happens vicariously. But what if we did not have to wait for others to tell the story that matters to us? What if performers, and non-performers, were able to find and create true catharsis themselves?

What if catharsis, education, and art could happen in a room filled with minimally dressed bunk beds, as a group of people share their common experiences through performance and improvisation? The Los Angeles Poverty Department is a theatre collective based in the LA with membership composed principally of houseless and formerly houseless people. The group is one of a number of affinity-based theatre companies that have propelled the movement of American theatre (see also: the Negro Ensemble Company, the National Theatre of the Deaf, and In the Margin Theatre).

Recommended read: An Ideal Theater: Founding Visions for a New American Art, edited by Todd London

State of Incarceration | Source: Los Angeles Poverty Department/Vimeo

State of Incarceration was a performance/installation/public education project created by members of the Los Angeles Poverty Department and performed in multiple locations, primarily in LA, between 2010 and 2011. State of Incarceration examined personal, social, and societal costs of mass incarceration at all stages of the complex. The work was staged such that performers and audiences shared the space without clear boundaries, and for at least some of the performances, the audience and performers alike sat in a playing space made up of bunk beds to represent prison barracks. The action of the play happened on beds, in the aisles between, and projected live onto the walls, evoking constant surveillance and a lack of privacy.

It is worth mentioning, when thinking about State of Incarceration in relation to play, that the work was not explicitly character-based but instead driven by common experiences of the co-creators which were then written and improvised into theatrical experiences. This is not uncommon in socially engaged art: many forms do not rely on protagonists, antagonists, or necessarily even fully constructed characters. This is not to say that it’s impossible to enact socially engaged art with characters and plot-driven structures: instead, SEA asks why one might need characters or linearity to tell a story, or whether we are free to stretch out into new, not-yet-created forms. Part of the inner-working of State of Incarceration is that the “roles” are so deeply personal, the players are portraying heightened, intentional versions of themselves and their experiences.

What if performers, and non-performers, were able to find and create true catharsis themselves?

The playing, then, in State of Incarceration takes the form of re-enactment, sharing space, and being in an experiential audience arrangement. It is also, here, an opportunity for healing and processing trauma. This piece would not be the same if not created in and with this community: if it wasn’t created by people who had been incarcerated, it would have instead had a ring of exploitation. Art for or about a community must be made by or alongside that community: this allows for genuine process and transformation. This, secondarily, allows true engagement, learning, and de-centering for the audience present. As renowned director Anne Bogart puts it:

“Art reimagines time and space, and its success can be measured by the extent to which an audience can not only access that world but becomes engaged to the point where they understand something about themselves that they did not know before.”

– Anne Bogart, And Then, You Act, 2007

Socially Engaged Art Insight #3: Co-authorship and Engagement

Socially engaged art is resistant to direct or individual authorship: rather, that which is made becomes the group’s work, and everyone who contributes becomes an active co-author. By subverting the hierarchy of artistic “ability” or knowledge, as well as the performer/artist-audience relationship, the work being done–the stories being told or issues being confronted — are democratized. The role of the artist, both in terms of “credit” or accolade is shared, as is the burden of responsibility and accountability. The role of the artist is not only to create, but to constantly question and evaluate.

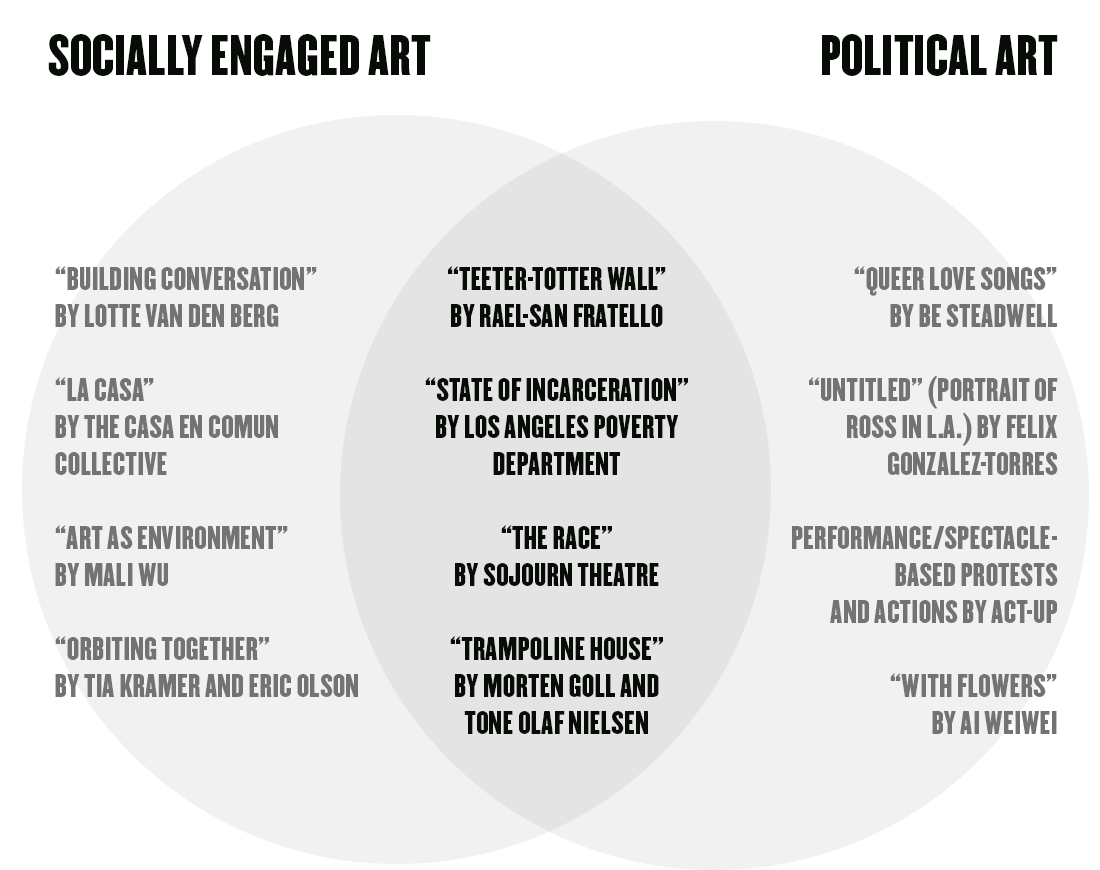

Most socially engaged art is inherently political, but the two are neither synonymous nor a matter of rectangle and square (neither is a category which can entirely contain the other). Instead, the differences create more of a Venn diagram, which can be illustrated through some examples below.

Building Conversation by Lotte van den Berg

La Casa by the Casa en Común Collective

Art as Environment by Mali Wu

ORBITING TOGETHER by Tia Kramer and Eric Olson

Teeter-Totter Wall by Rael-San Fratello

State of Incarceration by Los Angeles Poverty Department

The Race by Sojourn Theatre

Trampoline House by Morten Goll and Tone Olaf Nielsen

Queer Love Songs by Be Steadwell

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) by Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Performance/spectacle-based protests and actions by ACT-UP

With Flowers by Ai Weiwei

Suggested activity: Some questions to ask of this Venn Diagram

What does each project seek to accomplish? Who were this project’s co-creators? What are their backgrounds? What is the role of the audience here? What is being asked of us? How are we involved? What does the work center/make possible? How did time and place inform the message/themes? What philosophy or pedagogy can be applied elsewhere?

Play without Theatre: Culmination and Assessment

Here, we have seen play act as exploration and a prompt for engagement. We have seen it serve as a form of protest. And we have seen it provide catharsis and education. What can be deduced about socially engaged/political art from this variety of methodologies? How might we broaden those lessons towards a lens for political, social, or cultural engagement? How might we do those things in this time of COVID-19 and political uprisings?

Art as activism | Marcus Ellsworth | TEDxUTChattanooga | Source: © TEDx Talks/YouTube

There may not be any universal method for analyzing or understanding art for its social messages — nor do I personally believe there should be. However, here I will advocate for the following series of questions to ask when making or viewing art. It is by no means exhaustive but rather should give rise to further questioning.

- Who, and what, is centered in this art? What people and ideas do I center in my work or perspective of the world? What am I to understand from comparing these two?

- Who has contributed to and co-created this art? What attachments to the work do they hold? Is this information even made available, if so why or why not?

- How do I relate to this art? What space do I occupy in relation to this art, and how does that inform my engagement? Why am I drawn to this art?

- What people, places, identities, issues do I wish to create art about? What is my perspective and relationship to those topics or themes? What stories am I entitled to tell?

- Who do I need to connect with to make the art I dream of in meaningful ways?

By substituting the word ‘art’ out of these questions for ‘article’, ‘protest’, ‘news story’, ‘creative writing’, or any other medium of engagement, we may take steps towards more responsible and purposeful art-making and art-viewing. Again, as with anything, balance is key and play is still central to the practice of socially engaged art. The task is to understand how your art — or how you as an individual viewing art — can responsibly function socially and interpersonally without sacrificing the central tenet of play which fuels creativity, joy, and progress.

Note: While this article has drawn lessons from three main SEA projects (all of which were created partially or entirely within the United States) the scope of socially engaged art is broad in content, practices, and geography. The Visible Project and Art Making Change are two great resources to learn about a number of SEA projects that have happened and are happening globally.