SARAH GRACE VILLARREAL

When I was 3, I remember singing the alphabet song every chance I got. I knew it in two languages — English and Spanish. I remember my young mouth stumbling over some of the Spanish letters that made up a language that was not entirely mine, but also not entirely foreign. I remember feeling embarrassed because I couldn’t fully pronounce the words the way my mother did. But I was proud of the language. It sounded like my grandparents’ house, like the soft mumblings of the Spanish TV station, or the muffled words that snuck through my grandfather’s dark black mustache. It made me happy. It became a point of shame, however, that I never fully mastered the language. The thing is, everyone I knew spoke at least some Spanish — even white people. What I didn’t realize was how much Spanish I actually used daily.

Barbacoa | Source: Bruce Critchley’s Mexico Here and There

Living in South Texas — the area of Texas that stretches from the U.S.-Mexico border to San Antonio — you start to forget that the rest of the country isn’t as culturally Mexican as South Texas. While the rest of the country has probably eaten some form of a taco or hit a piñata once in their lives, it’s rare for them to know what a chancla is or to have tasted barbacoa (and not that stuff from Chipotle). Most of the U.S. doesn’t know the reality of using Spanish phrases and words as part of their daily vocabulary or the convenience of grabbing a breakfast taco on their way to work or school.

South Texas’ Cultural History

While all cities and regions have unique cultural identities, South Texas has a uniquely deep-rooted, deeply blended culture. South Texas’ Hispanic culture shifts as you travel slightly north into the Texas Hill Country, west into the dusty oil fields, or east into the piney woods. With the exception of the latter, the Tex-Mex culture persists, but not in the ingrained style of South Texas. You could call it Tejano, the Hispanic/Latino Texas ranchero culture, but I would venture to say it’s even broader than that. It encompasses city life, suburban life, and country life. This culture is South Texas, a tapestry of cultures existing as a sort of gradient along the southern tip of Texas.

Source: U.S. National Archives/Flickr

Tejano — this Hispanic Texan culture — and Norteño — northern Mexican culture — are the two primary influencers of South Texas’s Hispanic culture, with other Latino cultures slowly finding a place. Norteño and Tejano cultures exist as cousins, with similar upbringings but different experiences.

The rich cultural gradient of South Texas challenges the notion of borders.

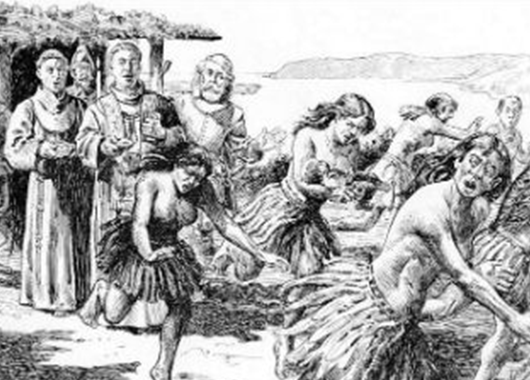

American Indians fleeing from Spanish missionaries | Source: © Bullock Texas State History Museum

South Texas culture also contains a melting pot of heritages brought by the many Texas settlers, including Czech, German, and American settlers/immigrants. American Indian tribal cultural aspects were not completely wiped out by the Spanish missionaries; whether intentionally allowed to survive or not, they still exist melded into the South Texan cultural fabric. The tragedy is that the majority of Texas’ first settlers — small Native American tribes — were absorbed by the Hispanic Texas culture. Little history is left of those first residents, but their DNA is mixed in many native South Texans as well as in our culture. Later, during the Mexican Revolution, the first major round of Mexican immigrants to Texas crossed an arbitrary line that partially naturally follows the Rio Grande River. South Texas’ demographics continue to shift and grow with every wave of cultures and immigrants that find their way to Texas.

The demographics of South Texas shifted through the years. Many German immigrants filled Texas and San Antonio, influencing the cultural landscape. As the Hispanic population became even more of a minority, much of the culture was not erased. Is it possible the Hispanic culture was used as a commodity to give San Antonio character in a young state? Maybe the Hispanic influence persisted simply because the culture was so ingrained in the population. One thing is certain — the Hispanic population grew again when Mexican immigrants fleeing the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th-century began moving slightly northward, no more than approximately 160 miles north.

In cities like San Antonio, immigration is a much more encompassing phenomenon — the border crossed South Texas.

San Antonio | Source: City of San Antonio Municipal Government/Facebook

San Antonio: A Gradient City

Established in 1718 almost 300 years ago, San Antonio is the oldest civil settlement in Texas and the largest city in South Texas. The Spanish first reached Texas in the 16th-century. Franciscan missions began popping up throughout Texas and converting local peaceful tribes to Catholicism, simultaneously absorbing the native culture while erasing it from memory. What these native people were left with was the beginnings of Tex-Mex culture — a new culture. Spain claimed the regions of Texas as well as Mexico as its own. Texas then became part of Mexico once Mexico gained its independence from Spain. American settlers began moving to Texas at Mexico’s invitation. However, San Antonio — which included South Texas — retained its Mexican culture even after Texas became its own Republic and well into statehood. From the earliest days of Texas’ statehood, San Antonio was touted as a “city of Old World charm.” There is a debate as to what the motivations were in Texas’ rise to independence and how many Tejano residents joined in the revolt, but one thing is certain — while most of Texas became increasingly white, South Texas held to its Mexican heritage.

San Fernando Cathedral | Source: © Texas State Historical Association

San Antonio exemplifies a cultural gradient in its architecture, its food, and artistic culture. Architecturally, Mexican influences can be seen in many of the local landmarks, like the San Fernando Cathedral, a Spanish Mission-style church that sits at the head of a bustling plaza in the heart of downtown. Modern Mexican architecture can be seen in other structures like the San Antonio Central Library, a structure filled with bright red-orange, purple, and yellow.

Many northern cities like Chicago or New York became gathering places for immigrating families. In cities like San Antonio, immigration is a much more encompassing phenomenon — the border crossed South Texas. The Hispanic population has been here since before the battle of the Alamo, paving a way for a culture to develop, retain, and evolve over the centuries into something not quite American, but also not quite Mexican.

Barbacoa and Big Red Soda — a staple weekend “brunch” food of many San Antonio natives,— is a perfect example of the blended cultures, and is so deeply San Antonian. Mexican barbacoa, which is traditionally made by slowly roasting the head of a cow in an underground pit, pairs exquisitely with the sparkling ruby beverage invented in Waco, TX. This blending and meshing of cultural artifacts showcase the gradient of Mexican culture in South Texas, mixing and diminishing the further north you travel instead of an abrupt change once you make it through the gate and over the river.

Is it possible the Hispanic culture was used as a commodity to give San Antonio character in a young state?

A Blurred Border

South Texas is American, highlighted by the city of Laredo’s annual celebration of George Washington’s birthday — a celebration founded to remind the rest of the United States that the border city is still an American city. Fireworks still fill the sky every Fourth of July. Baseball games, although only minor league, draw crowds in the heavy Texas heat. Cities like San Antonio and Corpus Christi have large military populations filling the region with patriotic pride. Politically, South Texas tends to be blue in a sea of red, unsurprisingly, since the South Texas population is primarily Mexican American.

Nuevo Laredo and the Rio Grande | Source: Pinterest

My grandpa lived in Nuevo Laredo, but moved to Laredo and married my Mexican-American grandmother. These cities straddle a line that was decided for them by the United States and Mexico. Nuevo Laredo and Laredo are just one of seven binational metropolitan areas along the Rio Grande. These border cities continue to be connected, enduring increased security as the years have gone by. Texans and Mexicans on the border rely on each other economically and socially, separated by a border designated only one hundred years ago. Laredo and Nuevo Laredo started out as one city. Political and national unrest forced the citizens of Laredo to move south of the border and found Nuevo Laredo. The two cities work together, despite national borders.

Arts, Culture, and Criticism

As you can imagine, South Texas offers the opportunity for Mexican-American performing artists to showcase their art, not only in classic mainstream performances but also in our own voices and through our own lenses. Mexican-American theatre’s presence in South Texas often blinds its residents to the miniscule representation in other parts of the country and, more importantly, in the mainstream media. South Texas has attracted Hispanic writers, filmmakers, and artists. Sandra Cisneros spent some time in San Antonio during the 1990s writing the bulk of her short stories in her compilation Woman Hollering Creek: And Other Stories about South Texas. Additionally, filmmaker Carmen Marron directed the 2015 film Endgame about a school chess team from Brownsville, TX. Back in 1999, the L.A. Times wrote that San Antonio was “an artistic and political mecca for Latinos,” highlighting the strength of San Antonio’s Hispanic culture while pointing out that there was a long way to go still. Well, 18 years later, San Antonio continues to grow and evolve.

The focus on Latino art does not come without criticism. A ballet teacher of mine once suggested that classical ballet held more artistic value than ballet folklorico. Ballet folklorico — or Mexican folk dancing, — is very popular in South Texas because it connects us to our heritage. She tried to explain that ballet folklorico had become far too common in San Antonio, too prevalent that it had become bland. She missed the significance, the essential meaning of ballet folklorico. It’s true that strolling down San Antonio’s River Walk, you’ll surely find one of two types of performance: Mariachi music or ballet folklorico. If you get lucky, you’ll maybe see them performed together. That said, although often exploited to attract tourists, folklorico loses none of its value as an art. There are levels of experience and expertise to ballet folklorico, just as in any other form of dance. Texas A&M in McAllen, Texas and UT Rio Grande Valley both offer degrees in ballet folklorico. It’s an important artistic expression of the Mexican-American and South Texan experience.

Ballet folklorico | Source: Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, Mexico City/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Some criticisms of San Antonio’s focus on Hispanic art strike a different chord. As a fellow grad student once pointed out, there are hardly ever any plays in San Antonio with parts for black actors. This lack of diversity in San Antonio’s theatre led her to write and produce plays specifically for black actors in San Antonio.

I continue to cling to the idea that diversity remains the best option, however, as we should appreciate that South Texas offers a place for Mexican-Americans to showcase their art on their own terms. Subtle criticisms of our culture pop up now and then, only to be subdued and not acted upon, perhaps because the dominant culture is solely Hispanic. For the most part, you see outsiders and people of other cultures move to San Antonio — or born in it — adopting the Hispanic culture and aspects of South Texas as their own. Because San Antonio is over 60% Hispanic, according to the 2010 U.S. Census, San Antonio’s Mexican culture dominates as the norm of the region, eliminating for the most part appropriation of the culture, since non-Hispanic residents simply adhere to the dominant culture. It’s beautiful, really, how opposite this is to the majority of the U.S. I truly believe that many of the non-Hispanic, non-Mexican residents of South Texas genuinely embrace the Mexican heritage and culture of South Texas. That does not mean South Texas is without its prejudices.

Classism and racism still exists, maybe not nearly as blatantly as in other parts of the south, or the rest of the country, but it still exists. San Antonio has some of the largest economic disparity between neighborhoods in the country, an issue that has been around for over 50 years. Similarly, the Rio Grande Valley suffers from some of the most devastating rates of poverty and malnutrition in the United States. A 2013 article from the Washington Post presented a bleak look at the lack of nutrition available to food stamp recipients of the Rio Grande Valley.

The Future

The stories of this region are colorful and inspiring. The people of South Texas are strong and kind, but often marred by stereotypes; stereotypes perpetuated in the media, and sadly by our current president. Yes, it’s dangerous across the border, but we Americans have enabled it — in more ways than one. Walls aren’t going to keep the bad people out. Walls won’t keep our culture out either. South Texas is an example of cultural evolution, taking parts of each parent culture to continue to evolve.

The rich cultural gradient of South Texas challenges the notion of borders. The culture exists despite national borders and political ideologies. Will it survive a violent physical severing of access to one of its parents? Of course. Will it survive an ever-growing hostile dominant American nationalism? Most likely. South Texas survived its first violent separation from its culture by evolving and adapting. It will survive the ever-increasing divide growing between the American people. I hope that there comes a time when America — as well as the world — looks to South Texas as an example of positive cultural evolution.

Walls aren’t going to keep the bad people out. Walls won’t keep our culture out either.