SWEDIAN LIE

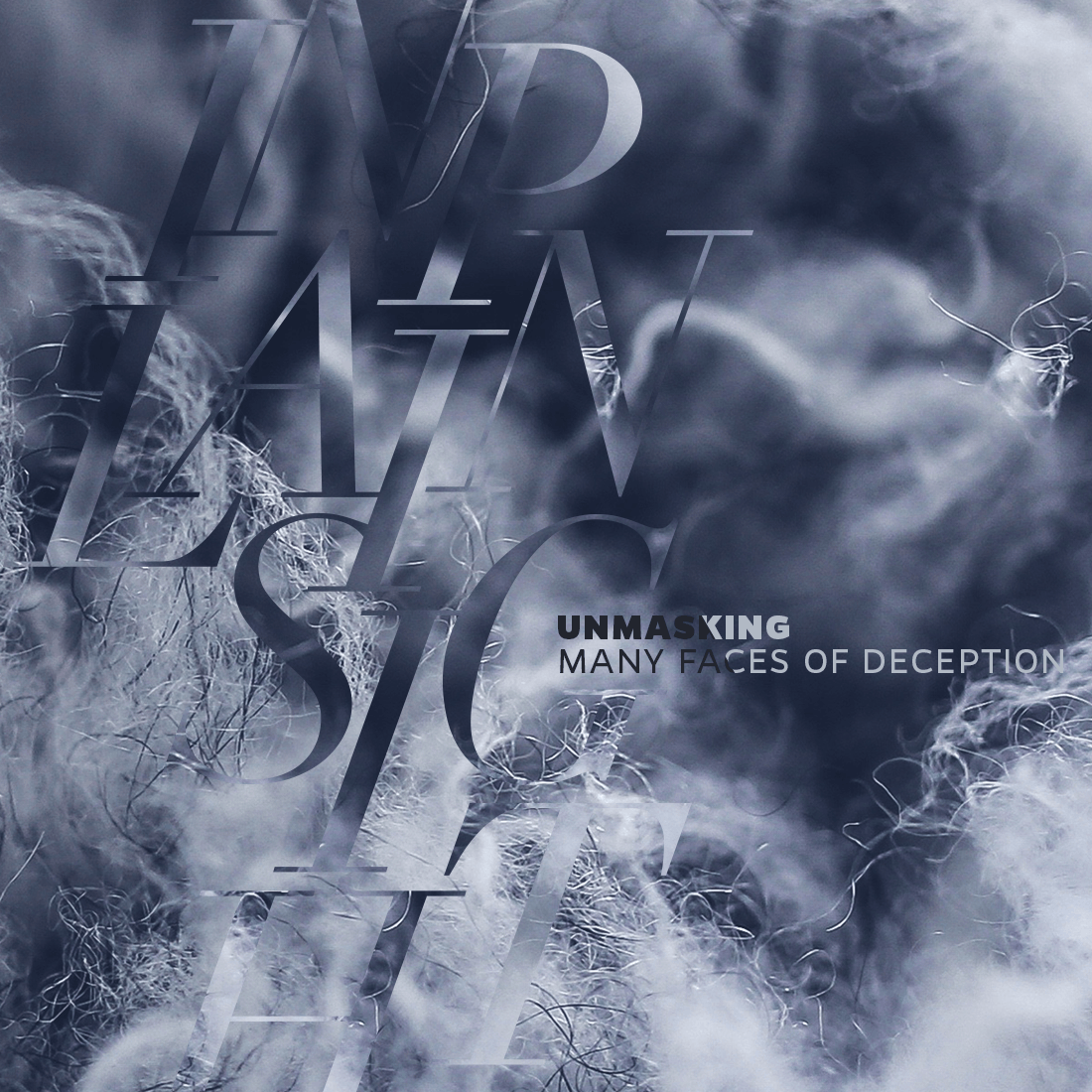

It’s 1974. Naples, Italy. Gathered inside Studio Morra that evening was a veritable who’s who of the Italian art world, with sharply-dressed critics, collectors, and art connoisseurs standing in front of a long table in this stark, bone-white room, preparing themselves for the latest work by a relatively unknown Serbian artist. On the table was an array of random, unrelated objects: there was a bell, a perfume bottle, a hammer, a lipstick, a bunch of pins, an axe, a gun, a rose, a lipstick, a Polaroid camera, a fork, a single bullet, and so on. On the other side of the table, standing across from the crowd, was a young woman in her late twenties, dressed in all black from head to toe. She stares steely into the audience, barely moving and never speaking. The clock strikes eight o’clock.

By the end of the night, at two o’clock in the morning, those very same individuals — individuals that one might call civilized and cultured — would be running out of the room, absolutely terrified as the young woman — now topless, bleeding, and wet — begin to walk slowly towards them. Yet until this moment, she has been motionless and speechless, while the audience has been anything but. So the question on everyone’s mind that night was not why the visitors are fleeing from her, but rather how did this young woman survive the night at all?

Rhythm 0 | Source: St. Mary’s College of Maryland

Instructions:

There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance:

I am the object.

During this period I take full responsibility.

Duration: 6 Hours (8 P.M. – 2 A.M.)

This was Rhythm 0, a performance that would go down as one of the most infamous and controversial works of art in modern history. And the young woman at the center of it all was Marina Abramović, who would go on to establish herself as one of the iconic artists of performance art. That fateful evening in southern Italy was not only a landmark work in the Abramović oeuvre, but also the first glimpse we have of Abramović’s attempt to answer a very important question — a question that, arguably, has haunted humanity ever since we humans can ask questions: in a world of infinite what-ifs, how do we fragile, flawed humans survive at all?

The Tradition of Asking What-If

This question of how to survive is an ancient one. Over the millennia, various writers and thinkers have dedicated their entire lives to responding to — if not always answering — this question. By the 19th-century, we have a definitive name for it: existentialism. Coined by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the term came to encapsulate this notion of responding “authentically” to the infinite expanse of possibilities that we call ‘life.’ For some, this meant embracing the distinctly human capacity for metaphysical awareness — also known as consciousness. For others, this meant succumbing to the inevitable dread and angst that comes with recognizing mortality. Somewhere down the middle are those who decided to laugh at the absurdity of the question altogether, sometimes in nihilistic fashion.

Concurrent to these philosophical inquiries, artists of various disciplines were also coming up with their own answers. By the mid 19th-century, there was a growing movement away from pure pictorial representation to a method of art-making that emphasized and venerated the human touch — a movement that will later be known as Impressionism. Fast-forward a century later, this same exaltation of a distinctly human artistry has now been completely overturned by the realities of not one but two world wars, resulting in the particularly dark themes and imagery of Abstract Expressionism. And, just like with the philosophers, somewhere in between the self-assuredness of the Impressionists and the melancholy of the Abstract Expressionists were the absurdist movements — Dada and Surrealism in particular — that made fun, through art, of the entire existential enterprise.

Monitor by Abstract Expressionist painter Franz Kline, 1956 | Source: Thinglink

As we enter the latter half of the 20th-century, these two parallel pursuits started to converge with the emergence of conceptual art. Founded upon the notion that ideas and concepts can themselves be art, artists begin to break away from traditional understandings of what constituted an art object. Two artists in particular paved the way for Abramović’s emergence, by carving — both literally and figuratively — out a space for themselves as artist-philosophers in the deep existential void of infinite what-ifs: Lucio Fontana and Yves Klein.

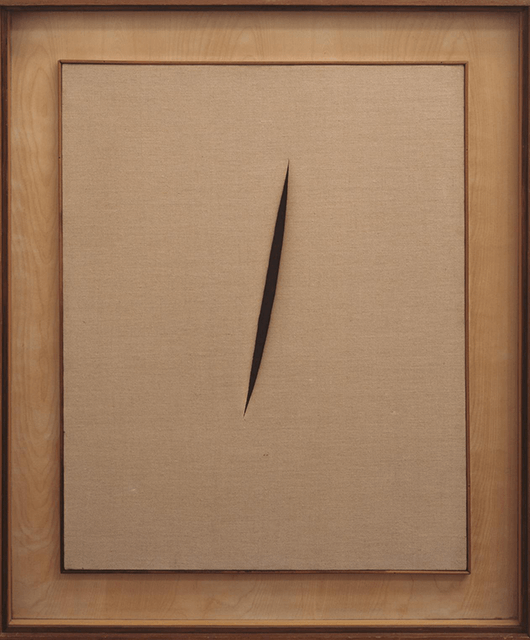

Spatial Concept ‘Waiting’ by Lucio Fontana, 1960 | Source: © Tate

Though more regularly associated with Arte Povera — an Italian art movement that used “impoverished materials” such as dirt and fabric to create art in response to the elitism of the art world — Italian-Argentinian artist Lucio Fontana was an early practitioner of conceptual art, in particular with his Tagli series. These were a collection of canvases that Fontana had deliberately cut and slashed into (“tagli” is Italian for “slash”). Fontana often draped the back of the canvas with a layer of dark black gauze to create the illusion of a deep and infinite void as one peered into the slash. With the Tagli series, Fontana wanted to break free from the confines of two-dimensional artistic traditions and reassert the artist’s presence in a distinctly explicit (and decidedly violent) three-dimensional way. Without the uniquely-human ability to wield a knife and slice through the canvas in a precise fashion, the canvas would remain a blank and naked fabric, devoid of art. Here was Fontana quite literally carving out a space for artists to create art in a three-dimensional fashion, opening up an entire world of what-ifs and possibilities — for better or for worse.

Pushing this notion of existing in and within “the void” further was French artist Yves Klein. A child of two avant-garde painters, Klein was exposed from an early age to the various artistic attempts at addressing existentialism. By the time he became a full-time artist, he was already a maker of art that no longer depended on the canvas — ranging from avant-garde musical compositions to photographic manipulations. It is with this latter technique that Klein would create one of his most iconic works of art.

Leap into the Void by Yves Klein, 1960 | Source: © The Met

Created in 1960, Leap into the Void is a photograph that depicts Klein leaping off of a high wall onto the asphalt road below. Suspended in mid-air and with no object to break the dramatic fall, one could reasonably assume that what happened next, after this image was taken, is something that’s perhaps too horrific and gory to show. This suspension of Klein’s fate represents that eternal question of ‘how do we respond authentically to life’ in a recognizably human form — in the way of a photographic “what-if” scenario:

What if Klein was Saved?

Do we want to save Klein and hope that, just out of frame, there was a fire truck or an ambulance that is on its way to rescue him?

What if Klein was in Danger?

Do we want to see Klein’s body splayed out on the hard pavement, blood and bones everywhere and the man presumably dead?

What if Klein was Us?

Do we want to be Klein; do we want to jump as well?

This now infamous photograph is actually a photomontage — meaning that the image has been doctored to erase the soft tarp that was laid down to catch Klein. The artist was never in danger during the making of this artwork. But what Klein has expertly created was a moment in which the viewer of Leap into the Void contemplated the existentialist question in a tangibly real and visceral way, precisely because there was a real human being’s existence at stake. The ‘public’ dilemma of existentialism became the ‘private’ dilemma of how do you and how do I and how do we react and respond to the infinite expanse of what-ifs available to us as part of our human existence. Once the question became personal, it can also become incredibly powerful and relevant. Thus, the logical evolution from Klein’s work would be, what if the situation was a live one? What if this very question came to life?

In a world of infinite what-ifs, how do we fragile, flawed humans survive at all?

The Art of Asking What-If, As Practiced by Marina Abramović

It is in this heady artistic-intellectual atmosphere that Marina Abramović emerged out of Studio Morra at the early hours of the morning, having given her audience that very opportunity to live out the question of infinite what-ifs — and, perhaps, questioning the wisdom of her decision. Looking at Rhythm 0 again, we see the same “what-if” scenario posited by Klein; but this time, we actually get to see how the what-ifs play themselves out.

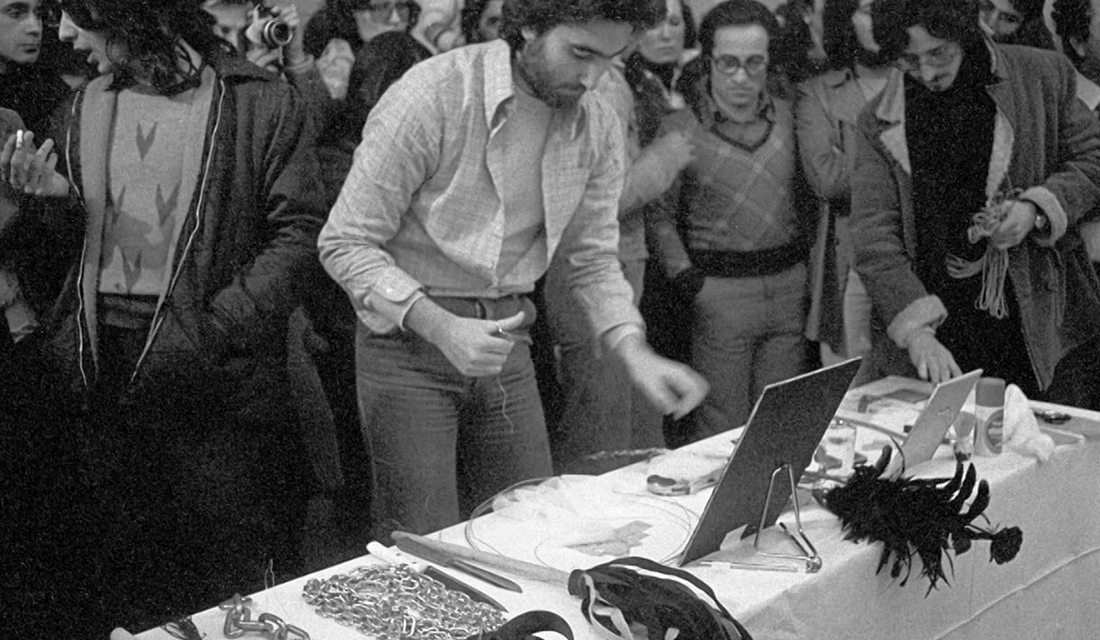

Audience members perusing the table objects available in Rhythm 0 | Source: Vimeo

What if Marina was Saved?

Should we, the audience, interact safely and gently with Marina so that she is never in any danger throughout the six hours?

What if Marina was in Danger?

Should we, the audience, push the premise of the performance to its logical extreme and harm Marina?

What if Marina was Us?

Should we, the audience, only do to Marina what we would allow others do to us?

Of the first what-if — a scenario for sympathy — Abramović remembered the following (these and other quotes are from Abramović’s memoir, Walk Through Walls):

“For the first three hours, not much happened — the audience was being shy with me. I just stood there, staring into the distance, not looking at anything or anybody; now and then, someone would hand me the rose, or drape the shawl over my shoulders, or kiss me.”

Of the second what-if — a scenario for antipathy — Abramović recalled the following:

“As evening turned into late night, a certain air of sexuality arose in the room […] After three hours, one man cut my shirt apart with the scissors and took it off. People manipulated me into various poses […] There was one man — a very small man — who just stood very close to me breathing heavily. This man scared me. Nobody else, nothing else, did. But he did. After a while, he put the bullet in the pistol and put the pistol in my right hand. He moved the pistol toward my neck and touched the trigger.”

Of the third what-if — a scenario for empathy — Abramović said the following, continuing the story of the man who placed the loaded pistol in her hand:

“There was a murmur in the crowd, and someone grabbed him. A scuffle broke out. Some of the audience obviously wanted to protect me; others wanted the performance to continue […] The little man was hustled out of the gallery and the piece continued. In fact, the audience became more and more active, as in a trance.”

Rhythm 0 | Source: © Lone Wolf Mag

As the piece approached its end, something unexpected — but truly authentic — happened.

“And then, at two AM, the gallerist came and told me the six hours were up. I stopped staring and looked directly at the audience. “The performance is over,” the gallerist said. “Thank you.” I looked like hell. I was half naked and bleeding; my hair was wet. And a strange thing happened: at this moment, the people who were still there suddenly became afraid of me. As I walked toward them, they ran out of the gallery.”

Within the span of six hours Abramović has — without actively engaging with the audience through any direct instruction or interaction — opened up the ‘void’ of human existence — this infinite expanse of what-ifs — and invited people to come in and respond accordingly. And the people, upon realizing how they have responded, were running out not because they were scared of Abramović the artist per se, but because they were scared of what they have become in her presence.

“The next day, the gallery received dozens of phone calls from people who had participated in the show. They were terribly sorry, they said; they didn’t really understand what had happened while they were there — they didn’t know what had come over them.”

In those six hours, the question became personal and alive in Abramović, and the answer that humanity gave was a mixed bag of results, to say the least.

What if… We Choose Sympathy?

In her early works — such as those of the Rhythm series — Abramović explored the threshold of pain and whether one can ever become “comfortable” and live in rhythm with pain as a part of being human and mortal. She was likely influenced by the Viennese Actionism movement — an early performance art movement that was led by Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch and performed extremely violent and destructive “Actions.” Blood, gore, and pain were frequent elements in these pieces. As such, Abramović’s preoccupation with pain was perhaps a logical response to the rhythm of existentialism: if there is a constant human what-if, it would be pain.

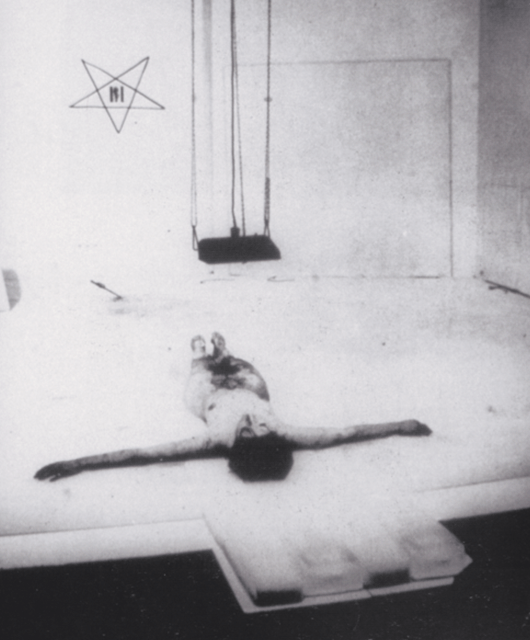

Thomas Lips | Source: Artwrite 54

In the 1975 work Thomas Lips, Abramović set out a pure scenario of pain and committed to it with her trademark iron will. The performance had Abramović consuming copious amounts of honey and wine, before cutting herself on the hand and stomach and lying down, naked, on a bed of ice, as a suspended heater blew hot air on her body, which enabled the bleeding cuts to flow freely. The idea was that Abramović would continue to lie on the bed of ice — and freeze — until the audience removed the ice from under her. Abramović described the pain as “excruciating at first,” but eventually she got used to it and the pain subsequently “vanished.”

What she didn’t realize was that in the midst of her transcending pain, the audience of Thomas Lips had recognized that she was in a very real and unplanned danger, not of freezing but of bleeding to death from the cut on her right hand, which was made when she broke a crystal glass with her bare hands. While the other cuts to her stomach were mostly superficial — deep enough to have blood flowing but shallow enough to heal naturally — this one was potentially life threatening. In the audience that night was Austrian artist Valie Export — herself a performance artist — who, upon recognizing the genuine danger, jumped up onstage and, with the help of other audience members, covered Abramović up and pulled her body off the stage, to be taken to the hospital.

“Because of all the other intense sensations stirred up in me by the performance, I hadn’t even noticed the cut was there,” recalled Abramović. Not only did she not realize the danger, she probably also did not anticipate the reaction from the audience. Performed a year after Rhythm 0, one would not be surprised at her skepticism. Yet that autumn night in Krinzinger Gallery, in the wintery city of Innsbruck, Austria, there was not only a performance in action, but also the human capacity to respond authentically to life with sympathy. Facing the constant human what-if of pain, the Viennese Actionists have chosen the what-if of violence; but that night, Valie Export and other members of the audience chose the what-if of kindness instead — shining a warm and bright light into the cold and unforgiving void.

What if… We Choose Antipathy?

Marina and Ulay | Source: University of Oregon

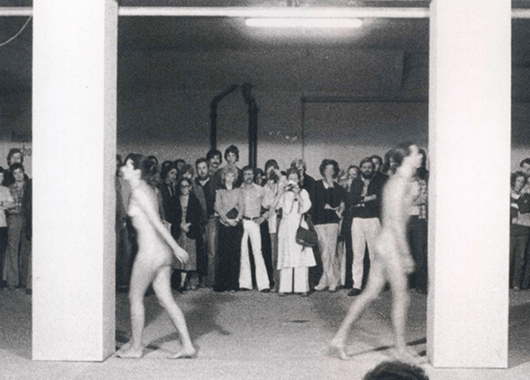

For every sympathetic audience member such as Export, there are many more antipathic audience members, unfortunately. Two years after Thomas Lips — and now working as a duo with her lover Frank Uwe Laysiepen, known usually as Ulay — Abramović and Ulay created a new piece called Expansion in Space. This performance had the two artists, naked and standing back to back, running away from each other towards hefty wooden columns that were four meters tall. They would collide with the columns — which would barely budge — and then walk back to the center in order to repeat the sequence again.

Expansion in Space | Source: Study Blue

Each column was designed to weigh twice the body weight of each respective runner, so Ulay’s column was heavier than Abramović’s. After a period of time whereby he was unable to make the column move even an inch, Ulay decided to stop performing. He left his position, put on some clothes, and joined the audience. Now it was only Abramović left. Without Ulay behind her, there was more room to run and gain momentum, and as a result, it became apparent that, eventually, Abramović would be able to move the column as she collided with it again and again. There was an air of excitement amongst the audience as they watched the gradual triumph of the animate artist against the inanimate obstacle. Yet something else was also happening.

“[Something] truly crazy happened. Some drunk guy in the audience jumped in front of my column with a broken beer bottle in his hand, the jagged rim pointed at me, and dared me to run into it. Strange or disturbed people, I’d found, had a way of being drawn to performance art.”

Once again, it was another fellow artist — American Scott Burton — who saved Abramović:

“Fortunately, the artist Scott Burton, who’d been watching, shoved the guy out of the way at the last second, and I kept running into my column — I was determined to success — until it actually moved a couple of inches more.”

In her commitment to the performance, Abramović had again put her life in very real danger — this time a danger that came out of an individual’s decision to react and respond to the performance with great disdain and negativity. Luckily there was someone else who responded with sympathy, but Expansion in Space is a visceral example of how antipathy is a very real human reaction to the infinite expanse of what-ifs, and it’s lurking at every corner.

As if to add insult to injury, later that night Abramović and Ulay found the van they have been living out of — filled not only with basic necessities but also archival footage and important documentation of their past works — has been robbed clean. The only things left were a couple of clothes that the couple’s dog Alba was playing with. Antipathy comes in all shapes and sizes.

What if… We Choose Empathy?

Throughout her decades-long career, Abramović has often designed performances that allowed sympathy and/or antipathy to be directly expressed as a response — but rarely empathy. This is in part because it’s very difficult to generate non-extreme reactions out of an audience, especially art audiences who are often stoic and expressionless. As she matured as an artist, however, Abramović has figured out certain methods and situations that created an environment whereby audience members can feel safe enough and relaxed enough to respond authentically with empathy to the performance at hand.

The Artist is Present | Source: © Marina Abramović/Art21

This approach is most evident in the iconic three-month-long performance The Artist is Present in 2010. Over the course of eight hours every day (ten on Fridays), Abramović would sit on a chair in the main atrium of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, while visitors would wait in line for the opportunity to sit across from her for however long they wanted to. Abramović would not move, eat, drink, speak, or even go to the bathroom during those hours. The performance — and the art — was, simply, presence; that of hers and that of the audience member’s. But to call it simple would be an insult to Abramović’s hard work and concentration. As she recalled, “The strain on my body (and mind) would be huge: there was no anticipation exactly how huge.”

The Artist is Present | Source: © Marco Anelli

In those three months — an accumulated 736 hours and 30 minutes — over 1,500 people came and sat across from Abramović. The empathy shown in these moments was so palpable and visceral that many were moved to tears, including Abramović herself.

“First you wait for hours just to sit in front of me. Now you’re sitting in front of me. You are observed by the public. You are filmed and photographed. You are observed by me. There is nowhere to go except into yourself. And that’s the thing. People have so much pain, and we’re all always trying to push it down. And if you push down emotional pain for long enough, it becomes physical pain.”

Reactions of sitters as captured by photographer Marco Anelli, compiled in the book Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramović | Source: © Marco Anelli/Hyperallergic

Throughout her career, Abramović has been obsessed with the idea of pain and how humans respond to it. Almost 30 years after Rhythm 0, in the expansive space of the MoMA atrium, she has finally found a way to look into the void and emerge in one piece. She has finally found a way for humanity to survive, and it’s by opening oneself up to others. It’s by being present. It’s by being a human presence against the infinite expanse of the what-ifs.

What if we respond to this life authentically, and just see what happens?

The Choice of Embracing What-If, As Practiced by You

Many of the philosophers and the artists who tackle the question of existentialism begin with defining the how of their approach: Should we be positive and assert our consciousness? Should we be negative and confirm our despair? Should we be absurdist and reject the premise altogether? Yet the heart of the question — this stipulation to respond “authentically” — is often relegated as an afterthought.

Source: © WeAreOCA

In her life as an artist, Marina Abramović has focused on authenticity in the search for answers against the what-ifs. While others have been prescriptive in their response, she has been descriptive: allowing space for people to react and respond in all kinds of ways, knowing that authenticity is a fluid process. We fluctuate in our responses to life’s what-ifs because we are mutable, mortal creatures. In fact, you are witnessing her unique approach as you’re reading this. What I’ve been prescriptively calling the what-ifs of sympathy, antipathy, and empathy, she has always described as something else: “an art made of trust, vulnerability, and connection.”

“You know, all human beings are always afraid of very simple things. We’re afraid of suffering, we’re afraid of pain, we’re afraid of mortality. So what I’m doing [is] I’m staging these kinds of fears in front of the audience. I’m using your energy, and with this energy I can go and push my body as far as I can. And then I liberate myself from these fears. And I’m your mirror. If I can do this for myself, you can do it for you.”

– “An Art Made of Trust, Vulnerability, and Connection,” a TEDTalk by Marina Abramović

Rather than being fixated with life as a constant barrage of what-if scenarios, perhaps the question that matters — the one we should really be asking — is, “What if we respond to this life authentically, and just see what happens?” Instead of asking questions and seeking answers, maybe we should be seeking connections instead. Perhaps deep inside the void of human existence is not a dark, eternally bottomless well, but a mirror that is just the right size for you, staring and waiting and looking for someone to simply share this moment we call life with.