KELLEY KIDD

When I find myself engaged in the American tradition of exchanging September 11th stories, mine begins with “I was on a plane.” When I say this, I become confused when people reply with their standard tales of distressed 4th-grade teachers. I respond externally with the appropriate reverence, while my internal voice, forgetting that our own stories are the most important to all of us, repeats, “Yeah, but I was on a PLANE.” Within my incredulity, I suspect, lies an awareness that when I say I was on a plane, I am not only describing my experience on that day, but touching on the experience that has left me feeling out of place in America ever since.

Like most Americans, I’ve told this story so often that it has become rote. What I often don’t have the opportunity to communicate — because it would be rather unpatriotic to do so in that moment — is that September 11th was also the day my parents and I left America to travel for a year. This experience, which I have also described more times than I can count, would become one of the most formative experiences of my life, shaping my sense of place, roots, and home.

Our Family in China

My parents both lost their jobs when I was 9, within a few weeks of one another. Prior to my birth, they’d intended to travel the world together, like any good young hippie couple. My unexpected appearance had thwarted that plan and set them on the path to domesticity and normalcy for the first ten years of my life. Now, I was old enough to walk without being carried and smart enough that my education was unlikely to suffer significantly from a year of absence (9-year-old me was confident — or arrogant, though 9 seems young for arrogance — enough to agree, as I understood myself to be simply speaking in facts when I told my classmates that I qualified to be two grades above ours). They weighed their options, and decided that this was an opportunity to go on the adventure they had been postponing.

They spent 6 months saving up at various odd jobs, and when all the other kids were starting their 4th-grade school year, we were packing up or selling all of our belongings. On September 10th, we boarded a plane to Texas, where we would transfer to a plane to Korea, then on to Beijing. We have a photo of my parents, my grandparents, and myself sitting at the gate playing cards. My grandparents had just tagged along to keep us company at the gate. The photo has a date stamp (anyone still remember those?) of September 10, 2001.

To keep a long, often-told story short-ish, after much confusion on our plane that involved scattered pages of a single copy of a multi-page memo being passed piecemeal around the plane, the flight that we had thought was going to Korea instead grounded in Alaska. We were marched out of the empty, locked down airport and carted off to a hotel in Anchorage — a lovely, though very cold, city. After two days there, we decided to carry on with our journey despite the protestations of our family and friends. “We’ll probably be safer out there than here,” expressed my parents. “We can just pretend to be Canadian if we really need to.”

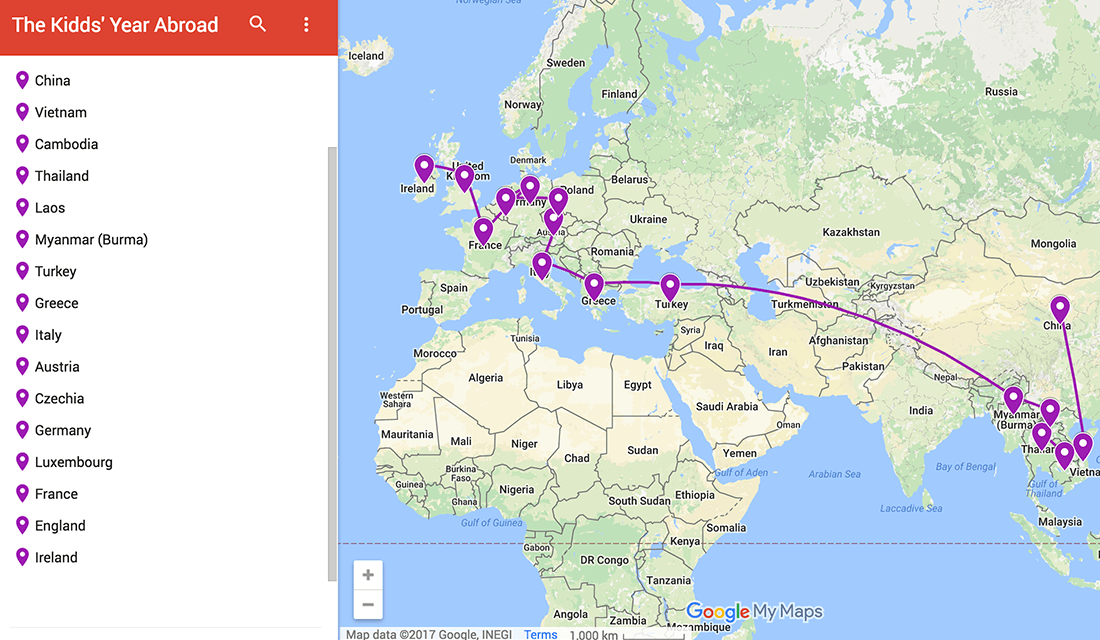

The ensuing year was spent backpacking across 18 countries, sweeping through China to Southeast Asia and then across Western Europe. Quickly, the bizarre became normal. People often ask me if I remember it, and I absolutely do — there are hundreds of vivid memories, both painful and beautiful, that shaped who I am now.

China, our first stop, was an overwhelming place for a hyper-sensitive, vegetarian, porcelain white 10-year-old to be. Upon our arrival, the nice hotel we had booked to ease us into the experience no longer had room for us. My parents, hoping to appease my enormous distress, sought out anywhere they could find that had a pool. The place we eventually found terrified us all. The pool was grimy, and when I jumped in, a lifeguard yelled at me for swimming without a swim cap. I got out and immediately started to cry, begging to go home.Slowly, the culture shock eased away, though being there remained extremely challenging. My primary complaint was that everywhere, the ground was covered with orange peels, something that — due to an odd fruit aversion of mine — disgusted me beyond belief. I got very used to people staring at me that year, being a translucently white 10-year-old child in China in 2001. My mother loves to tell the story of a woman in China (one of many) who started peering at me as I squatted over a toilet. This, like most Chinese toilets then, was a basin in the ground separated from the other toilets by dividers, but without a door shielding me from the eyes of anyone passing through. My mom tried to shoo the woman away, but I discouraged her: “Mom, it’s fine, I’m used to it.” My parents did their best to keep me comfortable, but the reality was that this place was more than I was ready for.

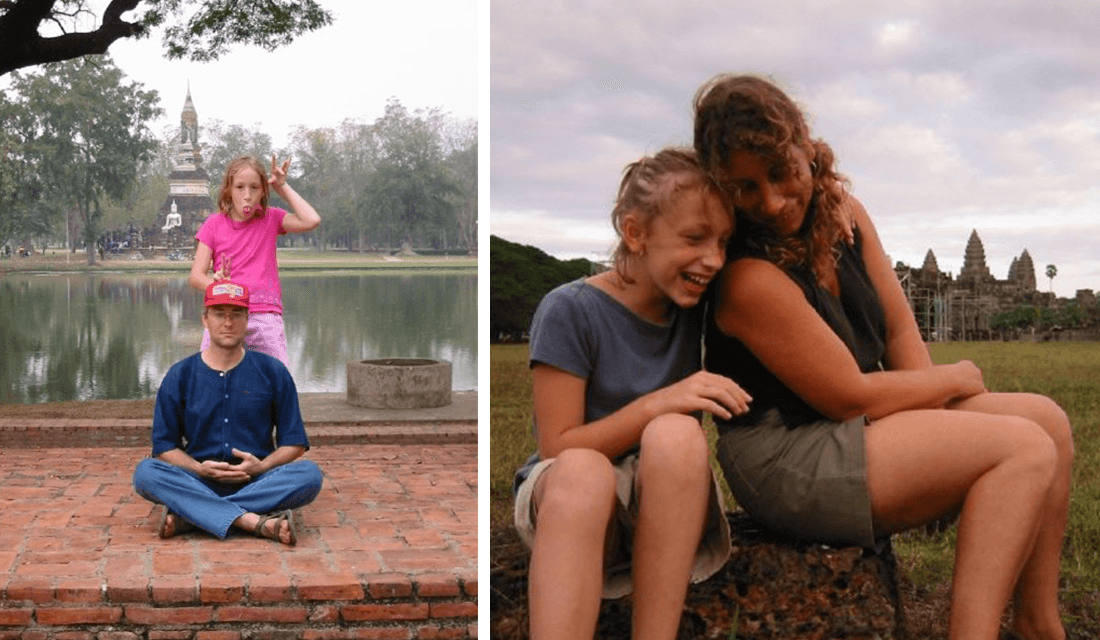

My father and me at Angkor Wat, at the spot where we would return exactly 10 years later

After many weeks dreaming of bread and peanut butter and clean streets, we made our way through Southeast Asia, which I fell wholly in love with. We began in Vietnam, then moved through Cambodia to Thailand and Laos, with a brief pit stop in then-Burma to renew our visas. The architecture in that part of the world moved me, as well as the nature and the people. I found myself drawn to the Buddhist art of this region and depictions of the Ramayana, the classic Indian epic that had been my bedtime story growing up. The photos from this part of the trip show my father and I replicating the poses of the Buddha and the demon Mara, gazing together in awe at ancient ruins, and my mother and I laughing joyfully as the sun begins setting over the stunning temples behind us.

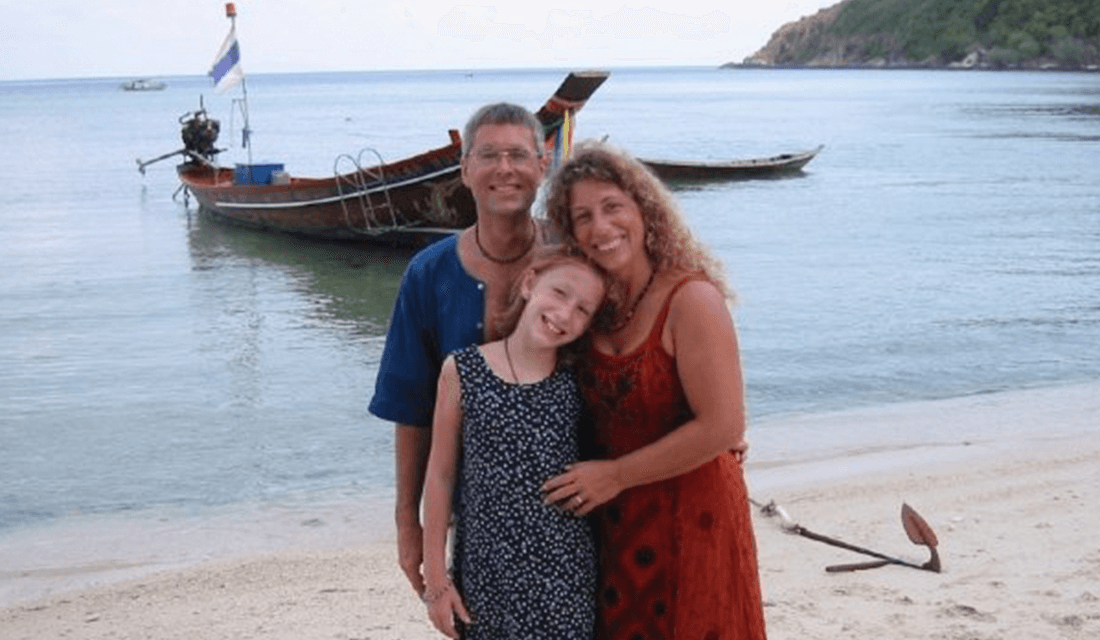

As we continued through Southeast Asia, I felt at home in the places we stayed and I settled in more easily. I became more comfortable making friends with people we met, there was finally bread to eat again, and the history was powerful and moving. Our stay in Asia concluded with a somewhat traumatic monkey bite — and subsequent rabies shots — but the pieces that stood out to me were exploring a jungled Angkor Wat and living ocean side in a hammock in Koh Pha-Ngan, eating my weight in curry.

We traveled to Turkey next, which punctures the memories of that year with a burst of rich colors, Muslim prayer calls, and the rich sweet taste and scent of apple tea drunk in rug shops. While there, I converted to Islam briefly, beginning my process of religious amalgamation that continues to this day.

Un pommes frites in Paris

My memories of Europe are comprised largely of goofy encounters with other tourists and a blur of architecture that I came to describe dismissively as “more old bricks.” In an effort to hold my attention while we wandered through an endless stream of European art museums, my mom offered me a nickel if I could find a ‘hiney’ in a piece of art. I thus made it my mission to find as many bare butts as I could in every museum we went to. For the David, I got a quarter. European history was somewhat lost on me, but I enjoyed the intrigue and drama that appeared in its art. I was deeply grateful for Italian food and family friends we met and stayed with along the way.

We lived on about $30 a day as a family and endured one another’s emotional roller coasters. We lived in close proximity, usually all in one bed due to our budget constraints. Occasionally, we would stay somewhere where I got my own bed, and those were the luxurious days.

Myself with our entire year’s worth of luggage

I spent the year reading anything I could get my hands on, which led my parents to scour bookstores in countries around the world for books written in English. I wrote lots of long, fantastical stories and forced hours upon hours of make-believe storytelling on my parents to relieve the boredom of long bus and train rides. We played cards day in and out, and we had one card game that we must have played in all 18 countries. When I spent time alone — which was fairly often as I sometimes refused to accompany my parents on their museum outings (and once even refused to travel to Burma with them when they went to renew their visas, something that resulted in us having to go out of our way to a different country to renew mine later) — I would play the first Harry Potter computer game until I knew exactly how to beat every stage of the game, or spend hours at internet cafes playing Neopets. Because I was being home-schooled, I played various computer games that taught me math and history, like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and Math Blasters. I played them all over and over, and the Thomas Edison portion of Carmen Sandiego remains etched into my memory.

When we returned to America, we found a vastly different home than the one we had left. In our absence, American flags had cropped up on every single front porch and trailer door in Knoxville. People’s fear of anthrax remained contagious, and the first set of shirts my grandmother bought me when we returned home included an array of patriotic American imagery, from the American flag to “America’s #1,” which I refused to wear. It was impossible for me to accept the premise that America was the best country in the world, when I had just seen, experienced, and loved (even though I sometimes hated) such a vast array of other places. I had met and cared about real people from 18 other nations, and the premise of picking a favorite appalled me — not to mention espousing the idea that one was objectively the best. I had heard murmurings of how people felt about America and Americans, and seen the way our culture looked from the outside. This further dissuaded me from buying into the idea that the ‘Number 1’ nation in the world was ours.

In an act of (probably slightly self-righteous) rebellion against these norms, I rejected the premise outright. My #1 shirt went unworn, and I omitted phrases to myself when we said the Pledge of Allegiance. While we had been gone, America had dug its heels into unwavering patriotism, and my uncertainty about the nuance (or the lack thereof) of this led me to an equally firm counter-stance.

From then on, I never quite felt at home in America. I vacated the South as quickly as I possibly could, straining to get out of the country as soon as possible, or at least to as distant a point from my hometown as possible. I tried to go to college in California, and when that failed, made my selection based on the quality of International Relations program. My application essays expressed my desperation to do whatever it took to spend my life continuing to see the world. Once in college, I planned to spend an entire year abroad, until the love of my school drew me to come back after a semester. Nonetheless, I still managed to split my one semester across two countries in an attempt to fit in as much travel as I could.

Some things don’t change

The goal of a career that would let me leave the country remained perpetually on the horizon. Yet, when the opportunities arose to pursue those careers, I also found some reason not to. My relationships were too precious to me, or the most obvious option — the U.S. Foreign Service — required the very devotion to America that I was so unwilling to espouse. I was intimidated by the prospect of applying to international NGOs without connections or experience, so I stayed domestic. The desire to leave the country remained a powerful feature of my identity, but one I found myself unable to pursue. It started to primarily operate as a way out, a tool of unavailability — I was unwilling to create roots where I was, to commit to relationships, or to be fully present in a place because I was always “about to leave” as soon as I found the right opportunity.

Eventually, I took a job at a translation company — finally, a real way out. Simultaneously, I entered the most committed romantic relationship of my life and moved to San Francisco, the city where I have always wanted to live. For a year, I continued to leverage the threat of my imminent departure. It was, in that relationship and prior experiences, an option in which I found safety and security when things scared me or I felt vulnerable. “I could always just leave,” I would tell myself. That was what I really wanted anyway. However, as year two began — and I slowly started to allow myself to experience the vulnerability of committing to a person and a place — I began to slowly feel a sense of home in a more real and grounded way than I had previously allowed myself to. The sense that time was short started to dissipate, and I began to trust that I had time to do everything I want to do in this beautiful city where I now live; in California, as far from the beautiful but challenging Knoxville, Tennessee as one can really get. Though my career offers me the best opportunity to escape that I’ve ever had, its draw on me has weakened as I rush less to escape the present. Where I had been rooted in my nomadic nature, I now find myself feeling rooted in a home.

All photos courtesy of the author.