MICHAEL DONNAY

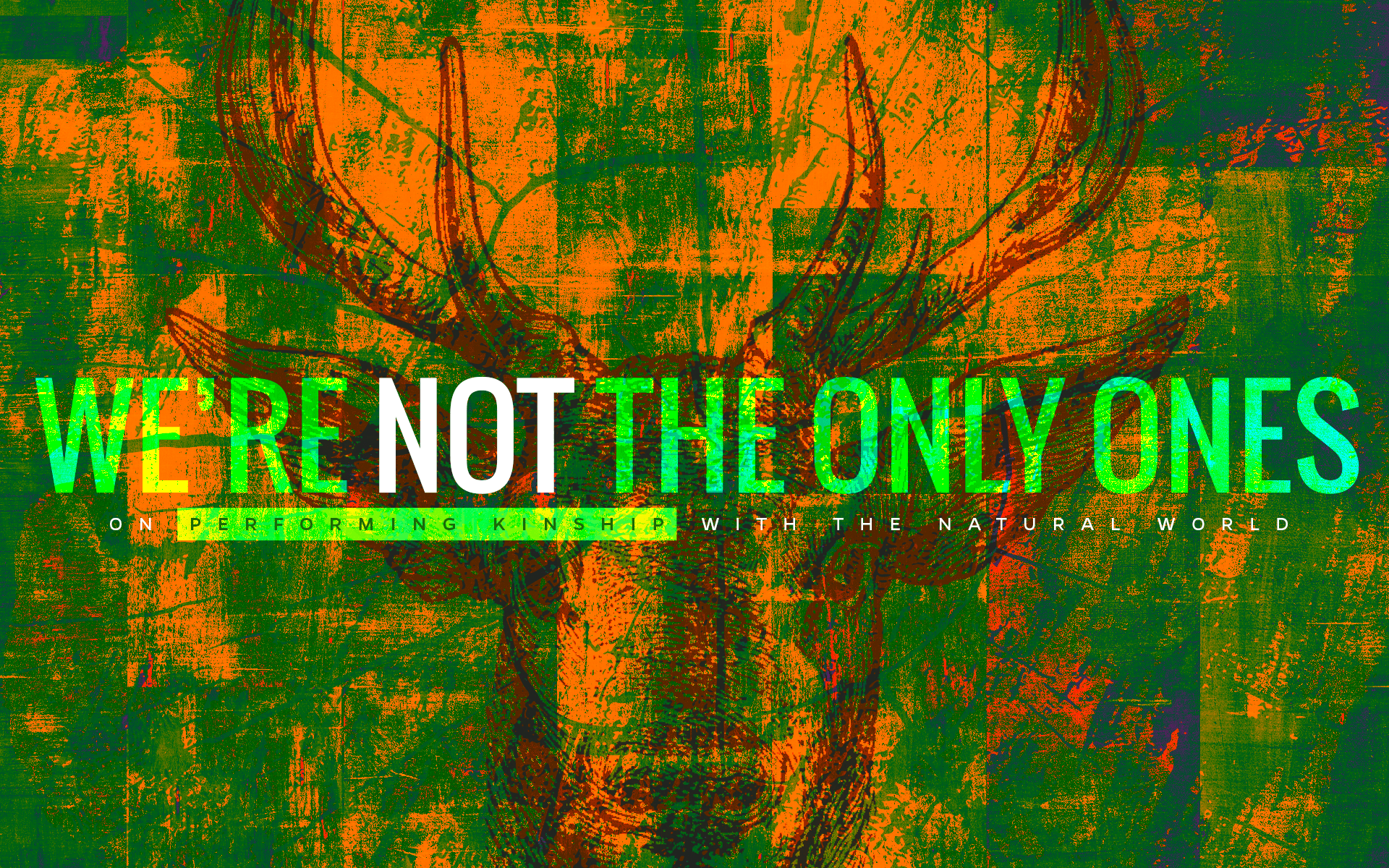

Anyone who has worked in a theatrical scene shop knows the sight only too well. The designs for the next production come in, accompanied by a truckload of steel and lumber. You and your fellow carpenters spend the next few weeks cutting, screwing, welding, and installing things — all the while dumping pieces of scrap large and small in the nearest dumpster. After long hours, everything is finally together and you can breath easily until it is time to tear it all down at the end of the show. Then the rush returns. Rather than trying to break it apart into recyclable pieces – “there just isn’t time” — it all gets tossed into the dumpster. You finish the day with an empty stage, an overflowing dumpster, and a restless conscience. Was there a better way to do that? A less wasteful way to build and to tear down? Unfortunately, you have no time to figure it out because the next production has already arrived and you have to get back to work. As one technical director has been known to say, your job is to build pretty trash.

Source: Stockholm Transport Museum/Flickr

You finish the day with an empty stage, an overflowing dumpster, and a restless conscience. Was there a better way to do that?

Until a few years ago, these questions of environmental conscience were not on the horizon for most theatre companies. This was just how things were done, and if anyone questioned it, the waste involved in building theatrical sets was just the “price of doing business.” However, in recent years the theatre industry has begun to develop a greater awareness of the environmental impact of its work. Beginning in the late-2000s, a number of major theatre companies started to collaborate on creating greener methods for producing theatre, especially building more sustainable sets. These early efforts culminated in a national conference on sustainable theatre in 2012. Since then, the idea of building scenery sustainably has gained greater traction within the commercial industry, as well as in community and educational theatre.

Community Forklift in Washington, D.C. | Source: © Ed Jackson/Community Forklift

When it comes to making theatrical sets more sustainable, the main focus in the last half-decade has been on using more environmentally friendly materials. Since most theatre companies rarely produce the same show two years in a row, the need to produce new sets every year means that theaters go through a substantial amount of material. As long as this production model remains the standard for American theatre, the use of consumables (materials that cannot be used more than once) will continue to represent one of the largest impacts theatre has on the environment. In an effort to mitigate this impact, theaters aiming to be more sustainable have generally pursued two avenues: recycling and reusing. Recycling involves using materials that have been reprocessed in the construction of scenic elements. Those materials can range from recycled paper for papier-mâché to recycled aluminum for structural supports. Depending on the scale of the project and the type of material required, however, using recycled matter can be expensive. For structural material, especially wood and metals, finding a company that recycles on the scale needed for some theatrical productions can be difficult. Given these challenges, using recycled material is rare in most theaters. Recycling is more common at the end of the production process, when sets are being taken apart, largely because the cost to recycle items is often lower than purchasing recycled products in the first place.

In recent years the theatre industry has begun to develop a greater awareness of the environmental impact of its work.

The other approach to sustainable construction involves reusing pieces from other productions. This practice has been common for a long time among smaller theaters, who often reuse pieces out of financial necessity, and devised theatre. Devised theatre — a style of creating plays that does not begin with a written script but rather relies on the performers to create the production — inherently involves using objects and materials at hand to create new work. Indeed, many of these companies view this reuse as an integral element of their artistic practice. Some theatre companies, like Pentabus Theatre in the United Kingdom, express this as an explicit commitment to environmentalism. Other companies that focus on devised work make this commitment clear without using the language of sustainability, but their frequent use of found objects or reused set pieces is nonetheless evidence of it.

Costume pieces and props lend themselves to easy sharing, but smaller scenic pieces can also be easily reused from show to show. The challenge comes with storing these pieces until they are needed — it’s hard to tell when exactly a theatre will need a mid-17th-century Parisian armchair – and so adequate storage facilities are a must. For small theatre companies, especially those without their own space, long-term storage can be impossible. Even large theaters can quickly run out of space after just a few seasons. In cities like New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago, with their high concentrations of film and theatre work, some outside organizations, like Materials for the Arts in New York, specialize in storing material for use by the creative industries. Where such organizations do not exist, theaters make use of home improvement salvage centers, such as Community Forklift in Washington, D.C.

Donyale Werle’s set for Peter and the Starcatcher | Source: © Donyale Werle

One of the most successful examples of both recycling and reuse in scenic design was the 2012 set for Peter and the Starcatcher, which was designed by Donyale Werle and won the Tony Award for best scenic design that year. Originally built for the 2011 Off-Broadway run, Werle and her team made extensive use of material salvaged from waste streams and existing set pieces from organizations like Materials from the Arts. Items that needed to be bought new — generally pieces of hardware that need to be new for safety reasons — were purchased from suppliers who held to sustainable standards of production. Werle was able to make use of some much recycled and reused material because she practices a type of design called “organic design.” Unlike traditional design processes, organic design starts by evaluating the materials available before any design is set in stone. The process was made easier by the style of the play, which tends towards fantasy, but Werle has used a similar design process for naturalistic plays as well. Her work is proof that sustainable theatre does not have to look like it’s built out of trash — even when it is.

How then can these theatre companies begin to be more sustainable? Perhaps the easiest thing is to build sustainability into their schedules.

BGA’s Times Square collection booth | Source: © Broadway Green Alliance

New York, with its unique concentration of theatre and film production, provides unparalleled resources for theatre companies looking to build more sustainable sets. The leading organization for green theatre there is the Broadway Green Alliance (BGA), a collaboration between the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Broadway League. BGA has taken the lead in organizing Broadway’s environmental efforts since its founding in 2008. There are currently over 25 Broadway theaters participating in ongoing initiatives, including repurposing costumes as senior prom gowns, binder exchanges through Actors’ Equity, and regular recycling drives in the district.

In addition to these ongoing projects, the BGA has a number of committees focused on greening particular aspects of the production process. These committees produce recommendations for venues on reducing their energy usage, for touring companies on how to transport equipment more efficiently, and for designers and technicians on the numerous ways they can create shows in a more environmentally friendly manner. The key to BGA’s language is more. They recognize that the greenest way to do theatre is to immediately stop producing theatre; short of that the best way to protect the environment is to invest in doing things in a more sustainable manner. Some of the recommendations are small, like buying reusable water bottles for the cast and crew rather than disposable ones. Others are on a larger scale, like using biodegradable material in set construction. BGA has also compiled a list of certified organizations that provide environmentally friendly services like construction recycling and set storage.

Across the pond in the United Kingdom, one of the BGA’s partner organizations, Julie’s Bicycle, leads the way in sustainability across the creative industries. Founded in 2009 by representatives from the music industry, Julie’s Bicycle has expanded to include the entire spectrum of creative work. Similar to the BGA, it serves three purposes: to research and establish best practices for sustainability in the arts, to distribute that research as broadly as possible, and to assist organizations in reaching the standards it lays out. To date, it has produced dozens of seminars and fact sheets about different ways to make the arts — especially the performing arts — more environmentally friendly. As befits its slightly broader focus, the resources assembled by Julie’s Bicycle include advice for a wider range of issues than the BGA material, touching on issues like outdoor venues, staff engagement, and merchandise purchasing.

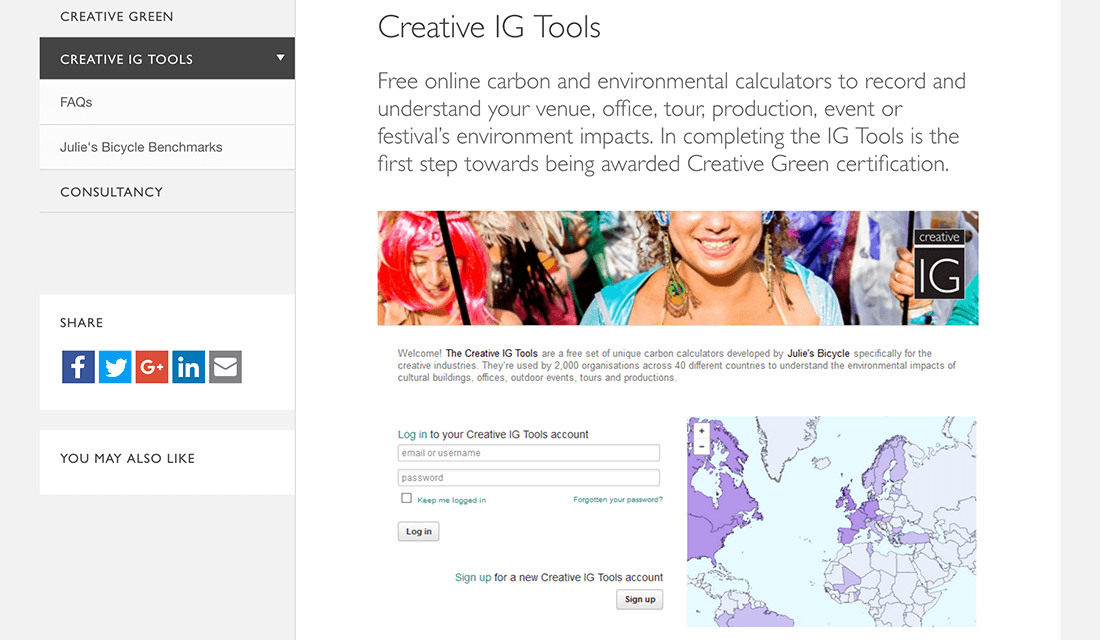

Julie’s Bicycle’s Creative Industry Green Tools page | Source: © Julie’s Bicycle

One of the most useful (and free) services provided by Julie’s Bicycle is a series of online tools for calculating the environmental impact of your production. Tailored to the creative industries, these tools provide information about carbon output, power usage, and waste generation. The Arts Council of England now requires all grant applicants to provide this information when seeking funding and Creative Scotland plans to add it as a requirement soon. These requirements will help make organizations more aware of the impact of their work, which is the first step to creating more sustainable productions.

The greenest way to do theatre is to immediately stop producing theatre; short of that the best way to protect the environment is to invest in doing things in a more sustainable manner.

While sustainable theatre making has grown substantially in the past few years, there is still room for improvement across the board. Much of that improvement will be intimately tied up with funding, as it costs more to build sustainable sets and to repurpose them at the end of productions. Unfortunately, the reality of arts funding in the United States is such that most theatre companies will not have the funding necessary to make those changes overnight. The small number of well-funded commercial and regional theatre companies have the resources, although whether they have the will is another question, and small companies are already borrowing or reusing set pieces because they cannot afford to build new sets for every production. Unfortunately, the medium-sized companies that make up the vast majority of the American theatre landscape are stuck in the middle. Their market share demands high quality productions, but they do not have the budget to produce them in a sustainable fashion. Many college theatre programs also operate under these constraints.

[Changes] require foresight and commitment from all levels of the production team to making sustainable construction a priority in each and every production.

How then can these theatre companies begin to be more sustainable? Perhaps the easiest thing is to build sustainability into their schedules. In addition to being more expensive, sustainable set construction can often be more time consuming than traditional methods. Environmentally friendly materials can be more difficult to acquire, meaning more time needs to be spent searching for them. Finding the appropriate set pieces in warehouses can also be difficult, requiring further time to discover. If something can be found, it can often require more time to modify in order to match the specifications of the design. Once the set has been built and the run of the show finishes, it needs to be “struck” (taken apart). Most theaters can ‘strike’ a set in a day, but doing so sustainably takes more time. Items need to be sorted into appropriate groups for recycling and donation — which often means breaking set pieces down into their component pieces. Many donation facilities do not provide free pick-up, which then requires staff members to take the time to transport items to the site to drop them off. All of this extra time quickly adds up, especially for theatre companies operating on already tight schedules.

In order for these sustainable practices to occur, production managers and technical directors need to build time for them into their production calendars. Depending on a company’s resources, this can mean building extra time into the beginning of design process to examine what materials are available before finalizing a design or adding an extra few hours to strike for sorting and disassembling set pieces. These changes do not have to radically disrupt current production rhythms, which are often compressed because of a lack of funding or staffing. They simply require foresight and commitment from all levels of the production team to making sustainable construction a priority in each and every production. An organization makes its values clear by what it makes time for. Theatre companies not only need to build sustainability into their seasons, but their production schedules as well. If they want to truly commit themselves to becoming more sustainable, they will make that evident in how they make time for it.