DOUG LEVANDOWSKI & JR HONEYCUTT

Doug just had a daughter in December, and she already loves games. Her current favorite is laying on her activity mat, which has various plastic animals hanging on an archway and a piano that she can kick with her feet. When she hits a key, a note sounds. Then, after a moment, a short melody plays: “Chopsticks” or a few bars of “Frere Jacques”. Her dad sits next to her, and she maintains eye contact with him while she kicks the comically large keys, and each time the melody comes in, Doug dances. When the melody ends, he stops dancing until she kicks another key. The rules are simple: kick a key, watch dad dance. It isn’t a complex game, but she’s eight weeks old and has a first favorite game.

The definition of a game is a bit controversial. Any definition that someone might tell you is ironclad is bound to have a few exceptions. For example, games don’t always have a winner or a loser. But the definition that we generally work off of is that a game is an activity where players follow a set of arbitrary rules until something happens to end the game. More loosely, we could also say something is a game if it’s fun and if you’re playing it because you want to.

What follows is a non-exhaustive list of what makes games fun. There are other things, and any one of these things, in isolation, probably isn’t enough to make a game fun — and not every game has each of these elements of fun included. But these are the pieces that designers can play with to create a game. After each way a game can be fun, we’ve listed a few games that we think do a good job of delivering that kind of fun.

But first, who are we? (as written by the other person)

JR Honeycutt is a professional game developer and game designer living in Texas and working wherever his laptop is. He has been full-time in the industry for almost four years and has worked on games like Seafall and Stop Thief. Currently, he works for Restoration Games, a company devoted to adapting old games for the current hobby market. Their current project that he’s most excited about is a re-release of Fireball Island. JR and a few of his friends also run Waitress Games, a freelance development and design company that is currently working on Betrayal Legacy and a few top-secret projects.

Doug Levandowski is a dude in Princeton, New Jersey who teaches at Princeton High School, but not really at “Princeton,” if you get what I’m saying. He’s a father and husband (but not to the same person). His design style is much like that of water flowing down a hill, in that he will eventually get it right because he is infinitely patient. His favorite games are Star Realms and Star Realms on the phone. He comes across as a very nice guy and then is actually a very nice guy once you get to know him. He co-designed and published Gothic Doctor, which is a published game about being a Gothic doctor. Also, Kids on Bikes.

Games Follow Rules

The world, especially in recent years, is a confusing, often horrifying place. It’s incredibly comforting to enter a world where there are clear rules, clear goals, and (usually) a clear way to win. As unsettling and uncertain as the world around us can be, it’s nice to know we can always travel to the island of Catan where it’s always a good idea to have a lumber port if you’ve built on a lot of forests.

Meet the Man Who Settled Catan | Source: © Great Big Story/YouTube

It’s also good to know that you’re sitting down with people who are agreeing to abide by the same rules that you’ve agreed to. You don’t have to worry about people playing by different rules — or lying to you about the rules they’re following. In games, everything is orderly. Even beyond that, there are certain unspoken and unwritten rules for games: don’t take someone else’s turn for them, don’t cheat, no punching; things like that. When we play games with people who follow these rules, especially when they follow them without any prior discussion, it provides a meaningful connection to others. It’s like a social trust fall.

It’s hard to give a list of games that do this especially well since this is one of the key components of a game.

Games are Escapism

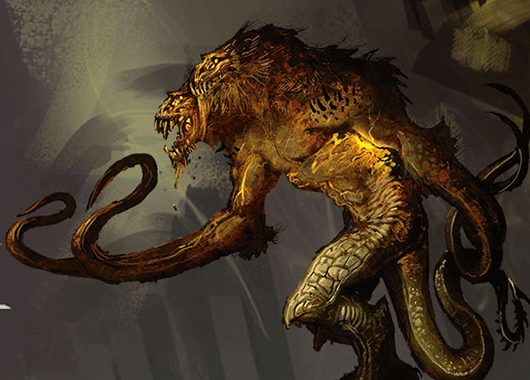

The Dungeons & Dragons Demogorgon | Source: © Dungeons & Dragons

Along those lines, games also let us escape the everyday world, regardless of the reason we want to escape. One of the most enduring games, Dungeons & Dragons, does this masterfully by sending players to a world where they can chop off one of the Demogorgon‘s heads with our friends. The value of being able to be someone else for a little bit helps us reach back to the days of playing “make believe” with our friends.

Often, games that do this best are the ones that develop a narrative over the course of the game. It’s very often the case that games where you play multiple sessions, like Dungeons & Dragons or any other game where you’re encouraged to take on the role of a character different from yourself. Other great RPGs include Kobolds Ate My Baby!, Monsterhearts, Fiasco, and the previously mentioned Kids on Bikes, which Doug recently co-designed.

[Each] time we play a game, we reset the rules.

Games Let People Feel Powerful

Games are great at giving people agency and letting them do things — or imagine that they’re doing things — that they would never be able to do otherwise. We can’t be Iron Man and take down Galactus, but in Legendary, we get to pretend we’re doing just that. Games let us play at powerful things that we’ll never, never get to do — and they let us do that safely.

On a deeper level, games set people on an equal footing in ways that simply don’t occur in the real world. Every time we start a well-designed game, all of the players have an equal chance of winning. In games for kids, luck plays a much larger factor because that’s what kids need in order to have an equal shot. Only a truly beefy five-year-old is going to beat Doug in arm wrestling, but The Game of Life is anyone’s game. As we get older and the intellectual playing field levels out, we’re better able to play games that require more strategy. Adults don’t want their lives left merely up to chance, and games for adults tend to reflect that.

The Game of Life | Source: Bustle

For games that do this well, it really depends on what kind of power players are after. In Dungeons & Dragons, as characters gain levels, they become increasingly impressive. Other examples are Sheriff of Nottingham, Dixit, and Codenames — and any sport that a person is good at and most video games where you get to bend the rules of physics.

Games Let Us Develop Expertise

The richest games are ones that we can (and want to) keep coming back to, keep learning about, and develop expertise at. Part of the fun of something is slowly working out the best strategies and figuring out how to maximize our successes and minimize our failures. And, each time we play a game, we reset the rules. In almost all cases, each time we sit down to play a game, the game’s slate starts clean but our mental slate doesn’t. Most great games gradually reveal themselves to us as we play. Early levels of video games, which start out easy and ramp up the difficulty, are one way to think about this. As we get better, the game gets harder.

Star Realms game board | Source: © Star Realms

On the tabletop, Star Realms is a particularly good example of this. It’s a game whose mechanisms are easily and completely understood after, at most, ten minutes of playing. But the interactions between cards are what make the game interesting, and seeing how all of the moving pieces can work with (or against) each other can take far, far longer to grasp. As a result, each game feels progressive as the player gets better and better at playing the game.

JR’s favorite is Magic: the Gathering, a game played by millions of people across the world with thousands of tournaments per week. It’s a game that has literally trillions of possible interactions between cards, and understanding the game at a deep level requires years of patience and practice. It’s a lifelong pursuit to be “good” at the game, yet it provides so many rewards for simply playing it that the process is often more rewarding than the result.

Scores of people playing during a Magic: The Gathering tournament | Source: Spikey Bits

Think of this way for games to be fun as an “expression of skill.” It’s very rewarding to demonstrate mastery of something we care about to others, much the same way an actor or musician derives enjoyment from their performances. This is true with a lot of games, but Doug has especially noticed this for himself in Patchwork, Burgle Bros, Convert, and Xenon Profiteer.

JR’s favorite board game in which skill is expressed is Mega Civilization. It’s a game of politics and negotiation across multiple fronts for about 18 hours of play, and it rewards players who are very flexible. This happens on a very public stage, and it feels quite good to win. Long ago, he also played Guitar Hero (a game built on the concept of performances) and loved playing it in front of other people, specifically to show off his skill at the game. The same is true of basketball, which he loves playing in front of people!

When we play games with people who follow these rules, especially when they follow them without any prior discussion, it provides a meaningful connection to others. It’s like a social trust fall.

Games Help Us Interact

Pandemic Gameplay Timelapse | Source: Giphy

Most board games require more than one person to play, making them a great way for people to interact with others. On top of that, they’re a structured way to interact with others, so for people with social anxiety, you have not only a reason to talk to folks but also guidelines for how to interact with them. Just as the rules for gameplay are clear, the rules for how to interact with others is clear. Playing chess? Don’t tell your opponent your plan. Playing Pandemic? Talk through what you’re thinking and get your partners’ feedback if you want to be successful.

The level of interaction that games have is a spectrum. On one end, there are games designers may call “multiplayer solitaire,” games where the decisions that one player makes don’t really affect others. In other games, the interaction is required for moving the game forward.

Games that are especially interactive include Wink, Between Two Cities, Merchants of Araby, Twister, Diplomacy, Bad Medicine, and Pit.

Games Let You Mess with Your Friends

As much as we love most of the people we play games with, it’s fun to get them once in a while. When we’re playing games, part of the fun can come from the competition: taking that queen that your best friend hasn’t realized is vulnerable or taking the last orange property so that your husband can’t get a monopoly there. In the real world, screwing over people you love is a psychological disorder. In many games, it’s encouraged.

Here, there’s a sort of bacchanalia aspect to games, where we get to suspend the rules that we normally abide by. We often call this the “magic circle” — that when you’re at the table, you’re okay to do what you want in the game. Doug and his wife are notorious for lying to and about each other in social deduction games like Secret Hitler or Werewolf — but away from the table, they’re completely honest and open with each other. There’s always something thrilling about the suspension of some aspects of the social contract.

Secret Hitler Gameplay, courtesy of the gang at Game Bang | Source: © Smosh Games/YouTube

Schrödinger’s Cats, Munchkin, Libertalia, Risk, Dead Last, and football are other great examples of games that do this well.

Games Have Climactic Moments

The classic Jenga tower | Source: Guma89/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

The same way that great literature has a moment where the readers’ emotions are released, so, too, do many games have great, pivotal moments. Usually, these are the final moments of the game, when you go out in gin rummy or when the Jenga tower comes crashing down after a few minutes of tottering.

Great games, though, often have numerous “big” moments to keep us engaged. In Seafall, a game that JR developed, this comes in the form of revealing secret information as your ship moves from island to island. Sometimes, these moments are another resource or two. Other times, they’re something surprising or unexpected.

If this sounds like your cup of tea, Lazer Ryderz, Pit, Wordsy, and Clue also do this well. In sports, each time someone scores, there’s an especially climactic moment. Boss battles in video games, too, do great jobs in giving you a strong, pivotal challenge.

Games Are Challenging

Our friend Dave’s four-year-old daughter loves Candy Land; for her, matching the colors is a challenging enough task to make it fully engaging for her. In psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi‘s groundbreaking work about motivation, Flow, he articulates that people are best engaged with a task when their perceived skill corresponds with the perceived challenge of a task. When this occurs, the person becomes engrossed in the activity, losing track of time, forgetting other needs, and feeling a deep sense of enjoyment and agency. Because of this, there is no one game that is appropriately “challenging” for all groups to make one of them fun.

The classic Carcassonne “meeple” | Source: Klo~enwiki/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Challenge is one of the main reasons that games that were fun for us as children lose some of their luster as we get older. Matching colors and moving the right number of spaces isn’t enough to challenge us anymore. But approaching the puzzles that we’re faced with in more adult games can be a great way to keep ourselves engaged and interested.

For games that offer some light puzzles that might be more appropriate for young teens, check out Constellations, Lanterns, and Cobras. For ones that pose more of a puzzle for adults, New Bedford, Carcassonne, Pandemic, and Acquire are great.

Every single person plays games, be they board games, card games, sports, or flipping around on a cell phone. As designers, it’s important for us to understand why people play: for many of the reasons listed above and, in a more basic sense, to feel good.

We love games for their capacity to engage us. It’s sometimes difficult to find meaning and challenge in day-to-day situations, so playing games allows us to release some intellectual angst that would otherwise be wasted on incredibly-accurate counts of the tiles on my floor or ceiling.

The world, especially in recent years, is a confusing, often horrifying place. It’s incredibly comforting to enter a world where there are clear rules, clear goals, and (usually) a clear way to win.

Plus, games provide a useful framework for social interaction. We don’t have to make small talk. We don’t have to worry about being excluded from a conversation, since my place at the table is integral to the completion of the game. We especially don’t have to justify our presence there, since we’re all there for the same thing.

Games connect us to childlike feelings, even when they present difficult challenges. Unhindered by the reality we leave behind when we play, we’re able to focus on less substantial and more immediate things.