ANTHONY REALE

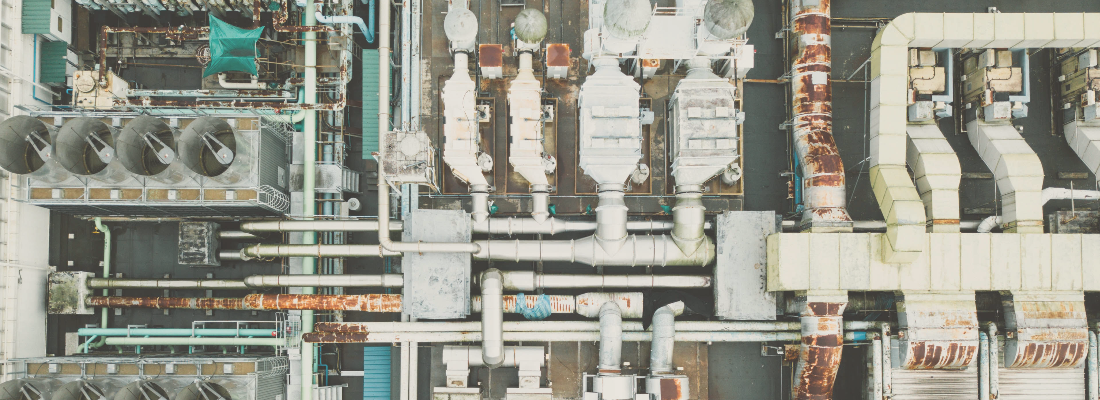

The best place to be in the world was the Laughing Brook Factory when it was steaming ahead full, placing tiny hats on toy elves and fastening wheels to tiny toy cars. This was something that CEO Kent Plentiful believed with his whole heart––when you heard the screaming of the machinery, you were feeling joy. Each clunk of the gears was a dollar sign in his bank account, and each worker felt good that they were contributing to something larger than themselves: joy! He was a little king on his mound, up in his 35th floor office in his Wagyu calf-leather swivel chair. Nothing discouraged him, and he put out fires better than the Laughing Brook Factory Fire Department ever could––metaphorically, of course. Literally sometimes too.

This master firefighter couldn’t believe his luck, until he couldn’t in a wholly different and difficult way. At the beginning of this fiscal year, the Toy Elf department suffered a flood that destroyed most of the conveyor belts in that area. Kent, who could outdrink Poseidon himself, was unable to drain the place. Following that quickly in the way that disasters do, the Toy Axe department suffered a bought of “Bordenistic issues,” with a series of gruesome familial murders; the Toy Axe department used to be the pride of Laughing Brook, seeing as the expert lumberjack Verdeen family made up the entire department. It was just unfortunate that Maxine Verdeen snapped one day and made mincemeat of her whole family. (Never fear, she was sentenced to a few years in the Lapham County Jail.) Following the Toy Axe debacle, the whole factory was forced to grind to a halt during the Giggling Virus pandemic that struck the country. The Centers for Diseases and their Control called the virus “a threat greater to this country since that idiot Klimpton was the Chancellor” so citizens would understand the severity of the issue.

The Giggling Virus ransacked communities, taking children from their cribs and smashing economies into dust. It was devastating to see how the systems of society, curated carefully on their teetering edge, would topple on into the abyss without so much as a farewell. Kent went through a depressive episode on par with Van Gogh. Instead of a blue period, Kent raged red, like a star expanding to swallow a planet. He would scream at workers for simple mistakes, drunkenly claim that no one would be quarantining, and push people in the hallway if they got in his way. Several quiet settlements went to certain employees who suffered remarkably severe injuries after Kent had shoved them down flights of stairs, against walls, or, in one case, through a conference room’s glass wall. No one joked anymore, as the sound of laughter had become frightening. The thought of Kent unleashing his anger on someone also kept things safely bleak.

He called me into his office to discuss what he wanted to do next from a manufacturing standpoint, so I went. I found him in a state of general discontent: pounding out aggressive emails on his keyboard, slamming his stapler down hard on various memos, and pulling hairs out of his mustache.

“Sit down, quickly,” he said.

“What seems to be going on, Kent?” I asked, not sure of what the answer could be, but knowing that whatever it was would probably be angry.

“Shouldn’t you know?!” He wrenched his computer screen toward me.

I saw several of our workers from the Floating Boats and Dirigibles department huddling around a roaring fire in an oil can.

“What’s this?”

“What’s this?” Kent asked, mimicking me. “You’re letting these quiet quitters quit loudly and completely!”

“They look…like they’re living in a trainyard. What’s happening?”

“You seem to be missing the point. Go. To. Them. And. Get. Their. Asses. In. Gear. Understood?”

I nodded quietly and rose to leave, still confused about why the good people of Floating Boats and Dirigibles were being forced to warm themselves over a fire.

“And Geoff?” he said, stopping me. “Get them working now, or get them on the first train to the unemployment office.”

He waved me away after that, telling me to close the doors behind me.

I headed back to my office, wondering if the bread line would be better than this. The grass was always greener in unemployment, but the lack of green made jobs seemingly necessary. Kent hadn’t always tortured me. There was a time before I had this job, when I worked as a typist in a legal office. Sure, it was painfully boring. Sure, it didn’t pay that well. Definitely, the lack of excruciating exchanges was such a pleasant aspect. But I found myself going home to my barren studio apartment each night with the urge to cry. The soul was being sucked out of me with each keystroke. My interests suffered, scurrying to the shadows––cockroaches leaving my overtired brain in search of a better sustaining force. Then, the Factory Foreman job appeared.

Working at Laughing Brook was an exciting challenge, each day an abstruse question answered by someone or something completely unimaginable: the chain smoking head of Flammable Baby Blankets had dropped her lighter, sparking a fire; the worried Endless Handkerchief team lead had a nervous breakdown after he found an end one day; and, my personal favorite, the Whistles team whistleblower incident of a few years ago. How could work have been so terrible before this? The suffering that I lay in previously all but evaporated the second I walked through Kent’s factory’s doors. Of course, this was all true until the Giggling Virus thoroughly scoured joy from the place.

I had arrived at the door that led to Floating Boats and Dirigibles and caught my breath. I wasn’t entirely sure what I’d find behind the ornately embossed wood. The scene of blimps landing at an oceanic port was so harmonious, a place where blimps and ships shared the plinths that jutted from the welcoming land. My reverie was interrupted by a large steel needle stabbing through one of the sunny blimps and nicking my arms. I yelped as I fell to the ground. The door swung directly into my shins, painful insult to bodily injury, and a barefoot boy leapt over me. He looked down as he jumped, shocked to see someone on the floor. My bloodied arm wasn’t enough for him to stop, and he was not keen on stopping. He had rounded the corner and disappeared by the time I stood up.

“Paul! Paul, come back!” the voice called after him, to no avail.

An older blonde woman appeared in the doorway. She yanked the needle out of the door, then saw me on the floor.

“Oh god, what happened here? Are you alright?” she helped me up before she was done asking her question.

“I’m okay, just nicked. That Paul kid’s got a hell of a 100-yard dash time, huh?”

“When he wants, at least. I’ve never seen him move that quick for something work-related. I’m Allie, the head of Floating Boats and Dirigibles.”

“Thanks for helping me up. Geoff.”

She winced like she had been stabbed by the needle.

“Geoff, like the foreman of this place?” she asked.

“The one and the same!”

“Great. Second day on the job, and I got my boss stabbed. It’s all looking great.”

“Could be worse,” I said, trying to show I wasn’t upset.

“Let me know when it is, and I’ll believe you when I see how. You were coming down to our department?”

I paused for a moment, wondering how to discuss the tree Kent was barking up.

“Just wanted to meet the new department head, and see how things were going. Mind if you show me your processes?”

“Absolutely, come on in! I can also show you to the bandages so you don’t bleed out on my floor,” she said, laughing a little.

“That would probably be for the best, not dying during a walkthrough,” I said, feeling my face flush a little.

She led me inside, waving her hand at a completely normal interior. Nothing appeared as it was in the camera feed that Kent had shown me! The floor was operating normally, the workers were manning the belts, and nothing was out of order. What had Kent shown me?

“Everything looks…great?” I managed to say.

“Is that a question? I try to think things look good here in Floating Boats, you know.”

I silently kicked myself for showing my confusion to Allie. She didn’t need to know about Kent’s theoretical problems with her department. Had he edited the video to make it look like a live feed? Why would he do that?

“Sorry, I was lost in thought,” I said. “Everything looks good. Just a random check.”

“That’s a relief. Can I offer you the band-aid fix?”

“What? Oh, sure.”

She handed me the bandage while trying to search my face for answers.

“Are things really okay, Geoff? You look a bit like you’re going to hurl.”

“Truly, everything’s good,” I replied. “I’m just thinking about the next things I have to get to.”

“It never ends, huh?”

“Never.”

“Well,” she hesitated before finishing her sentence. “Come back any time. We’re good hosts here.”

I thanked her and turned on my heel to leave. I turned when I reached the door, just to take another look, like things may have changed after I started out. I merely saw Allie, looking at me like I had completely lost all my marbles. She must have been wishing that she were some sort of psychic, I bet. There wasn’t enough time to try and explain myself further; I had to figure out if Floating Boats was actually lighting fires to stay warm! Could this be some sort of strange test that Kent put together? Would he go through the immense trouble of setting up a film set inside the factory in order to just torture me? I hated this.

My office was no comfort, with its simulated ponds and meadows playing on the window screens. Everything was corroding, the fake images––or were they real?––telling me stories about how my job could, should, or shouldn’t be. I pulled up the live factory feeds on my computer to see if I could catch Floating Boats in the act. Maybe Kent was right, and Floating Boats had removed their facade of normalcy after I left the room. Maybe I was going to catch them in the act right now, catch them unawares! The feed buzzed with static for a moment, then showed me everything as I had seen it. Everything as I had seen it! I fell back into my chair in disbelief. The world didn’t shudder with the weight of this trick, it simply muddled forward in its sameness: my desk was just as cluttered, my window screens displayed their bucolic digital lies, and my lamp in the corner flickered the same amount as before. It was only me who was perturbed.

I couldn’t tell if I was losing my last marble, but it sounded like my name was being whispered under my desk. My vision went brown as my beleaguered brain tried to understand how voices could come from the floor. I bent down, trying to sightlessly see, but found my forehead colliding with my desk instead. After some scrambling around, I heard Kent’s voice coming from my phone.

“Geoff, goddamnit, how long does it take to pick up the phone?”

“Sorry, sorry. I guess I dropped it under my desk.”

“I don’t care. What the hell is going on with Floating Boats?”

“Everything…was normal there. I went and checked in with Allie and found nothing.”

Kent didn’t say anything for a few moments. I could only make out the sounds of him typing on his computer.

“Geoff, do you find it fun to lie? Is that your idea of a good time?”

“Kent, I––”

“Shut your mouth when I’m talking to you!” He paused, then spoke viciously. “Pull up the camera feed to Floating Boats. Now.”

My vision hadn’t fully come back from hitting my head yet, but I slowly crawled my way out from under my desk. Brown clouds swirled, not abating in their blinding storm. Groping around led me to my computer, where I could just make out my screen. The feed from Floating Boats devastated me; it was the same image of the two workers warming their hands over an oil drum fire.

“That’s Paul,” I muttered to myself.

“What was that?” Kent asked. “Were you working up the courage to apologize to me?”

“I––uh––yes. I’m sorry, Kent, I don’t know what’s going on here.”

“It doesn’t seem that complex, but maybe I can slow it down enough for it to penetrate your thick skull. Go. To. Floating. Boats. And. Get. Them. To. Fucking. Stop! This isn’t the goddamned 19th century, I’m not some Scrooge. We have central heating for Christ’s sake!” he yelled. “Now. Repeat what I have said back to you so I know you understand it this time.”

I laughed, the type of thing that you can only do during moments of supreme discomfort or pain. What else is there to do when someone so efficiently decapitates you?

“I’m waiting, Geoff. Don’t make me ask again,” Kent growled.

“Kent, I heard you. I’ll take care of it.”

“I don’t think you understand. I’m not hanging up until you repeat back what I said so I know you fully get what I need from you.”

“Kent, really?”

“I have all day to wait.”

“Okay, I’m going to go to Floating Boats and get them to stop lighting fires to stay warm,” I said, understandably strained in my delivery.

“Just get to it. Idiot.”

He hung up, letting me still wonder if he was serious. I guessed that he had to be, and got moving.

The air in the hallway that led to Floating Boats felt thicker; I felt it holding the same muggy confusion that I had been wandering through. I stumbled a few times, letting the heavy air push me down. When did the trip to Floating Boats get so long? The hallway looked to be changing lengths, doors coming closer and backing away from me like I was some carnival attraction. The fluorescent lights bent downward, hands trying to scrape me. I stumbled, reaching out for the wall to try and brace myself, but the wall recoiled. I fell to my knees, closing my eyes in a feeble attempt to make the delusion go away. To my surprise, a few moments like this soothed me. I opened my eyes, and the hall had returned to normal.

The door was the same, with its idyllic port scene slightly marred by the place where Paul had pushed the needle through the door. The hole was in the hull of a boat marked “S.S. Indomitable.” I pushed it open, expecting what I had seen before; it had begun to feel a bit like Kent was making all this up. Conveyors and clean factory floors couldn’t hide flaming oil cans like that. They just couldn’t. I looked around and saw that I was right: the scene that Kent had shown me twice now was truly false. No oil cans, no flames, and no workers warming their hands. Despite having what I had seen before confirmed, I felt the wind go out of me. What was happening? Why was Kent doing this to me? Were the workers here suffering somehow, and we weren’t seeing it?

“You’re Geoff?” Paul asked, startling me.

“Paul?”

“You’re Geoff?”

“Yes, I’m Geoff. The one you stabbed, you know,” I replied, without thinking.

“I––yes. Sorry, that was an accident. I lost control of my tools.”

He looked sheepish enough, but distracted.

“Paul, have you noticed––”

“Please, listen to me,” he interrupted. “You have to listen. We are having problems here in FB&D with Allie. She doesn’t let us take breaks or even sit down. She locks the fridge so we can’t eat anything. People keep passing out, Geoff. You have to do something, please!”

Before I could say anything, Allie rounded the corner. Paul yelped and scurried away before I could say anything else to him.

“Geoff, I’m beginning to be concerned that something’s wrong here,” said Allie.

“I’m going to ask you a strange question, Allie. One that will make you question my sanity, if I’m honest, but I have to ask it.”

“Okay, shoot.”

She was searching my face for an inkling of what was about to come out of my mouth.

“Have your employees been…lighting fires in oil cans to stay warm?”

Her look contorted into something from the realm between horror and confusion—a place where the amygdala threw its hands up in despair and shouted its resignation.

“Geoff, no. Have my employees been lighting fires? No!”

“Kent has shown me videos of them doing just that twice now. I don’t know what to believe at this point, but I have to check,” I said, trying to seem reasonable.

“Are you alright?”

I broke completely when she asked me that, letting tears of frustration roll down my face. It was obvious that no one had lit a fire in this department ever, yet I still had a terrifying, nagging feeling that an oil can was just around the next corner. It would be so nice to sit by a fire right now. I found myself wishing that this inane rumor was somehow true, so I could join the rest-denied grunts of Floating Boats in a moment of peace and warmth.

“Geoff, I’m not great with this stuff, but do you need to sit down? Talk about it?” Allie asked.

“No, I—I have to talk to Kent. Something is wrong here.”

“Are you in the right state of mind for that?”

“No. But when have I ever been,” I said, turning to go.

Allie didn’t push further after that. As I closed the door, I heard her roar out Paul’s name. Her voice had changed, killing any kindness she had reserved for me. Now she was the superior, and her will would be done—probably to Paul’s detriment.

I stumbled around the halls again, mostly sure that I was aimed at my office. The maze of hallways did not provide any clues or hints toward where I was going. I found the ornate yellow door of the Rubber Ducks department. Rubber Ducks was leagues and miles away from my office; how had I gotten here? The charming scene of ducks taking flight didn’t provide any answers. I tried to reach out and touch the scene, but the door kept moving away from me. The ducks flew higher, the water drained from the lake, and the trees shrunk to mere matchsticks as my shaking fingers attempted contact. Even when I thrust myself forward to try to close the gap, the door taunted me, scuttling further out of my reach. I turned away from the scene, trying to find a nearby wall to cling to. No luck.

Now I found myself down the hall from my own office. The walls stayed evasive, letting me stumble around without so much as an apologetic look.

“Geoff, where have you been? I’ve been in your office for almost an hour now!”

Kent was standing in my doorway, which had somehow shifted to be near the ceiling. I looked up at him, squinting to see if he was an apparition.

“Stare at me all you like, I’m not going back to my office until you explain yourself.”

He waved me inside, but I had no idea how to get up to him to talk in my office. I stood, childish in my stasis and waited.

“Well? Did you find the fires in Floating Boats or not?”

“No,” I said.

My voice sounded submerged, a fatality in the community pool.

“Did you spend any time looking? I still see them warming their hands, like we live in poverty! This can’t have been that hard. Go to the department, stop them from being fuckups, and get praise from me. Is that so difficult, Geoff?”

Before I could say anything, he flew into my office in a fury. I couldn’t see him for a moment, until he reappeared and hurled a stapler at my head. The pain rippled down from my head into my stomach, but failed to snap me from my altered state. The door remained near the ceiling, where Kent was now hurling a keyboard down at me. I happened to fall down away from it, but no such luck with the paperweight that followed.

“You are worthless, Geoff! You’re nothing!”

He stalked off, muttering under his breath. I lost sight of him as he turned the corner, then my eyes closed.

As I lay in pain, I saw a rural fisherman. He was successful enough, with a home and a family all dressed in cable-knit sweaters. The small community he lived in relied on his catch for food, livelihood, for their town itself. He would go away to the wild sea each day to find these enormous fish that would be sold or picked over, filletted or chummed. And each day, while he looked over the churning waves, wondering if today would be the day that he would pitch himself into the sea. This man whose work was so crucial to so many, found that he could never escape the role he’d accepted so readily. It was so good to be needed for so long. Then things soured, and he couldn’t find a way out. Every trip out on the ocean was so necessary that it made him sick. There was no way he couldn’t go every single day of every single year of his life. This man stood in front of me, hat in his hands. I looked at him, seeing all the lines on his face, the toll that time had taken on him. He crumpled into his clothing, body turning to dust in front of me.

I awoke in my office chair, startled. The meadows and lakes in my window screens were there as usual, and everything on my desk was in its place. There were no clues as to how I made it back to my chair. I sat awhile, staring at the paperweight that Kent had thrown at me. It was an award from the previous year for “Best Foreman” from the International Organization of Foremen. The base of the paperweight––glass with suspended letters spelling out my name––had the smallest chip in the bottom left corner. I held it up to see it in the light, and dropped it as my phone rang. It shattered as it hit my desk, the shards scattering their way everywhere they pleased. I picked up my phone, and before I could say anything, Kent spoke:

“Geoff, get moving. They lit fires again in Floating Boats. I can’t believe I have to talk to you about this again. Handle this!”

I giggled quietly, then dropped the phone from my hand. I would find the truth if it killed me.