LORRIE DAMERAU

Language is more than a means of communication; more than just vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. By combining these sounds and gestures in specific ways, we translate the disconnected fragments of thought in our minds into coherent sentences that we can share with others. Through language, we travel from within to without, from our ideas to our actions. By being the mechanism through which we express ourselves in the world, language is more than just communication, but is itself an action.

By engaging with [said] vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, one brings a particular identity into existence.

In 1955, J.L. Austin introduced the idea of the performative utterance. These utterances are not quantitative statements of truth or falsehood. Instead, these utterances perform an action. One of the examples Austin presents is the “I do” said at a wedding. This statement functions as an action, as a “speech-act.” The performative utterance is a statement that brings forth an action into existence. Without the statement — without the words spoken — the act does not occur. Through the performative utterance, language has power and meaning beyond just helping people express their thoughts. Language creates an action that brings something into existence. For example, speaking a language is a way of embodying a cultural practice and a way of expressing ethnic or national identity on one’s body through the spoken word. Speakers create a connection to a unique cultural history and to fellow speakers around the world.

Because language is a powerful mechanism for the transmission of identity, it is crucial to study the roles that language plays in the political sphere. How does language create or perpetuate a national identity? How have governments and societies used and abused language to serve their own purposes? This article claims that language is ultimately a means of unification by creating a common way of thinking, speaking, and acting — even if the language isn’t necessarily common. Using Singapore as a case study, we see that language can unite a diverse population, create a unique cultural identity, and help a country carve out its place in the world.

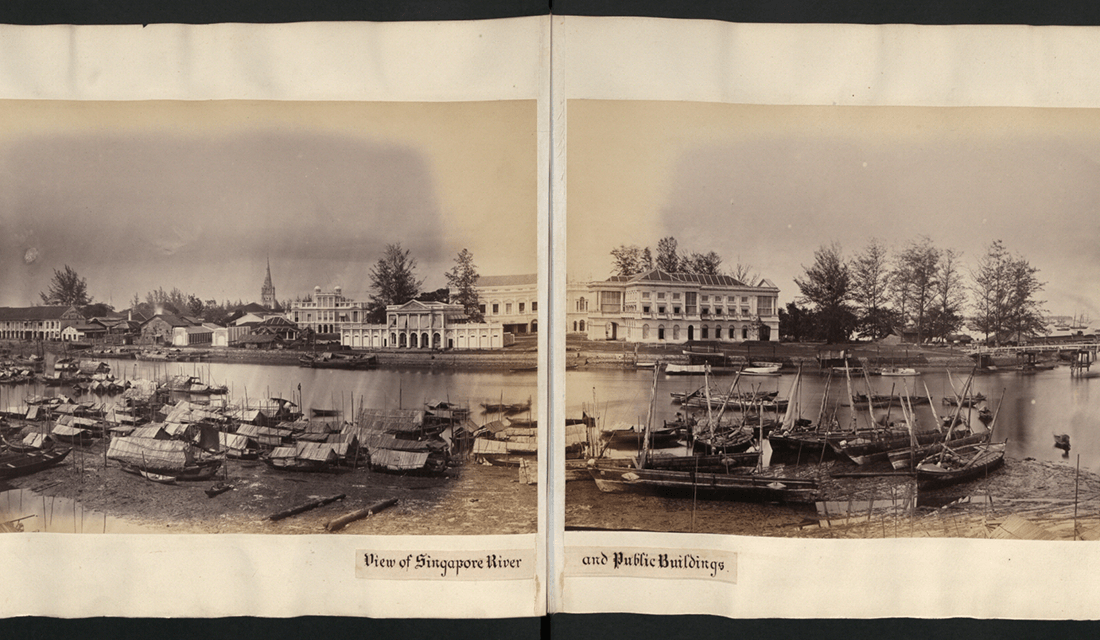

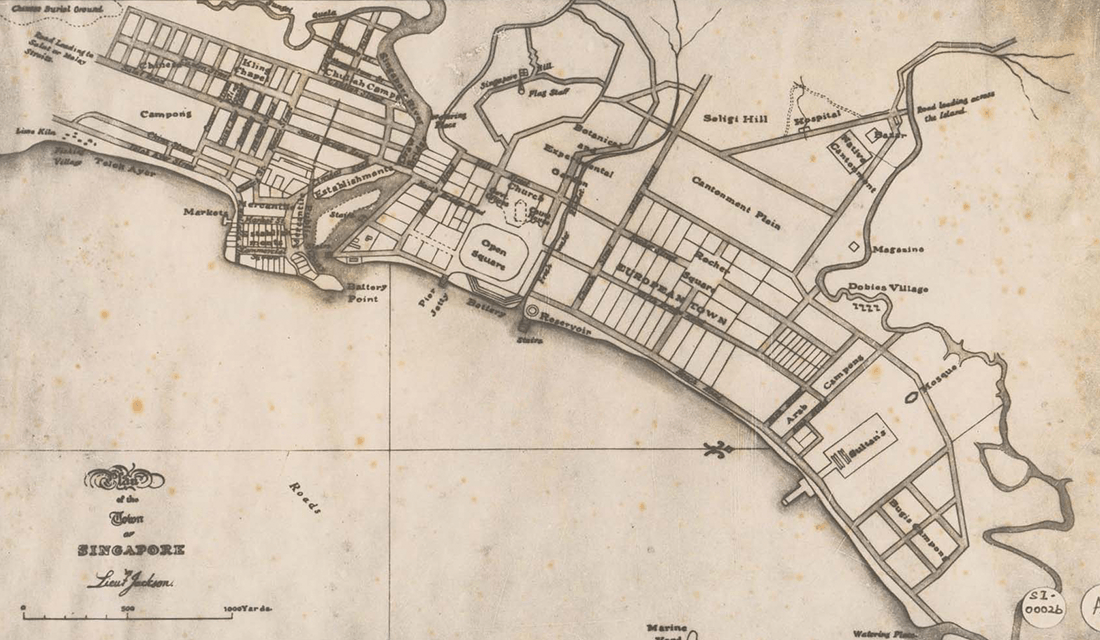

Source: The National Archives U.K./Flickr

Background on Singapore

Modern Singapore has its origins in the trading posts of European colonial powers. The British arrived in Singapore in the 19th-century and signed a treaty with Malaysian leaders to establish a trading post — a free port — on the island. Traders from all over the world flocked to the island and the population diversified and expanded. In 1822, colonial leaders divided Singapore into ethnic functional subdivisions, segregating ethnic groups into four residential areas: European Town, Chinese Kampong, Chulia Kampong (where ethnic Indians lived), and Kampong Glam (where Malays and Arabs lived). Effects of this segregation can still be seen in the present-day.

The Jackson Plan, which divided Singapore into ethnic neighborhoods | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Lee Kuan Yew announcing the forming of the Federation of Malaysia (the merger between Malaysia and Singapore) on 16 September 1963 in Singapore | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Singapore remained a British colony until World War II, when it was taken over by Japan. Britain reclaimed Singapore after the war, but the damage was done. Singaporeans demanded independence. Britain gradually devolved governance to local authorities until social unrest and protests in the 1950s won the establishment of the State of Singapore, with Lee Kuan Yew becoming the first Prime Minister. In the early 1960s, Singapore briefly merged with Malaysia, a move that dissatisfied the ethnic Chinese majority. Racial tensions between the Chinese and the Malay and external Southeast Asian politics resulted in independence in 1965.

A small country with no natural resources and high unemployment, Singapore needed to figure out how to establish itself as a successful sovereign state. They joined the Commonwealth and began focusing on strategies to promote the country’s economic growth and standing in the world. Using English was a way of cementing and promoting the new government’s aspirations and agendas for becoming a modern, successful country.

Speaking a language is a way of embodying a cultural practice and a way of expressing ethnic or national identity on one’s body through the spoken word.

Language as Creation

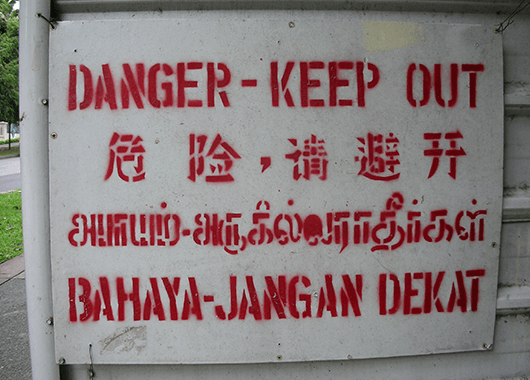

While many former colonies have multiple national languages, Singapore’s official language policy is unique. With no real indigenous community, the official languages (English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil) reflect the influence of colonialism and immigration throughout history. The multiplicity of language embraces the diversity of the nation, ensuring that the major ethnic groups have their languages represented, but using the lingua franca of English to include other minorities. Practically everything in Singapore is printed in four languages. English is often first, followed by the other three. By listing English first, Singapore avoids showing favoritism or granting primacy to one of the main linguistic/ethnic groups, thus promoting a united national identity. In the words of Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, “We decided to opt for English as a common language and it was the only decision which could have held Singapore together. If we had Chinese as a common, national language, we would have split this country wide apart…” With a history filled with moments of racial and ethnic tension, choosing the language of one group over another would have been disastrous.

One could claim that to be Singaporean is to have multiple identities: to know and understand the ethnic community of one’s ancestors but to also experience and live in the diversity of a modern-day city.

A warning sign in Singapore’s four official languages (from top to bottom: English, Chinese, Tamil, and Malay) | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Through using English in schools, business, and government, Singapore brings about an identity that is unique from the ethnic groups within its population. A Singaporean may speak Mandarin with his or her family (thus enacting a Chinese identity) but likely speaks English when out and about in the city. While the groups exist in enclaves around the city, the continued intermingling of the ethnicities promotes an equal intermingling of culture and language. A native Hokkien speaker goes to a Malaysian part of town and eats Malaysian food. A native Malaysian speaker goes shopping in an Indian part of town and hears Tamil. A native Tamil speaker works in the center of town and conducts business in English. The different groups and ethnicities assimilate into a broader Singaporean community and learn to express and perform a new Singaporean identity. This is an identity that enjoys prawn mee soup, fish-head curry, and bak kut teh equally. An identity that will walk past a Hindu temple, a Buddhist temple, and a mosque all on the same street. All of this is achieved because Singaporeans have a lingua franca, even though they may speak a different mother tongue at home. And, most importantly, that lingua franca doesn’t belong to any of the major groups.

Using English was a way of cementing and promoting the new [Singaporean] government’s aspirations and agendas for becoming a modern, successful country.

As Singapore grows older, English is becoming the language most spoken at home, according to a 2016 government survey. Over 35% of residents use English most often, and nearly three-quarters of the population are multilingual. Many adults likely grew up speaking Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil at home but now speak mostly English in their own families. One could claim that to be Singaporean is to have multiple identities: to know and understand the ethnic community of one’s ancestors but to also experience and live in the diversity of a modern-day city.

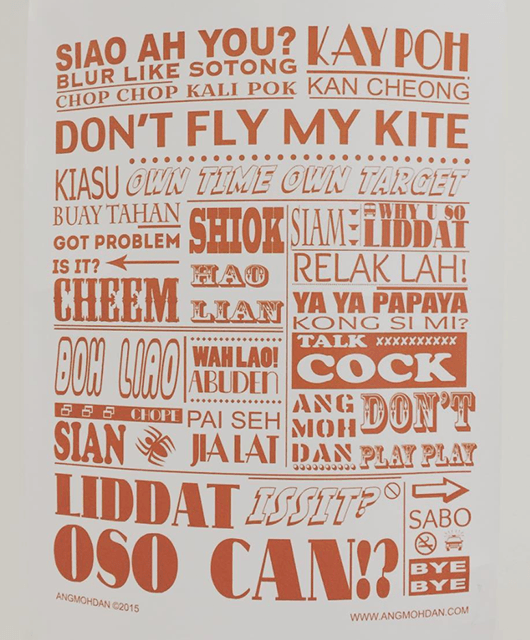

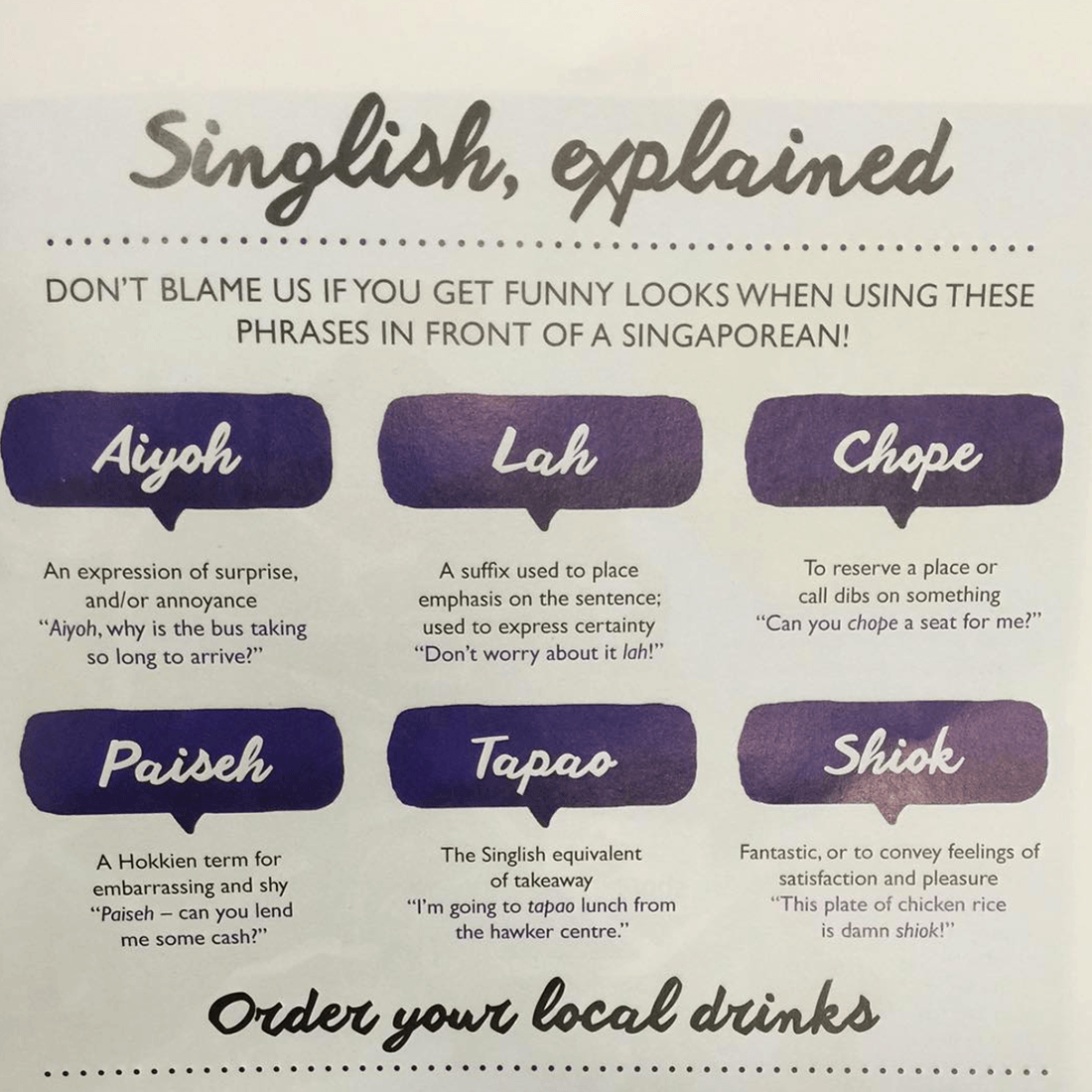

A sampling of some classic Singlish phrases | Source: wingie_x/Instagram

Singapore is also experiencing a linguistic phenomenon whereby the four main languages mix together and create a new language. Since the end of colonialism, the four languages in Singapore have been melting together in a unique patois: Singlish. Upon initial listen, Singlish may seem like broken English peppered with Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil phrases. But dig deeper, and Singlish emerges as a unique language in its own right. Borrowing the best bits of the parent languages, Singlish is efficient, dynamic, and playful. It is uniquely Singaporean, shaped by all who speak it without regard to ethnic origin. Those who speak Singlish are creating not just their language, but also their national identity. English is a carry-over from colonial rule; it is distinctly something foreign. Singlish, in comparison, is native and homegrown. It belongs to Singapore and only to Singapore. As one The New York Times op-ed argued, “[Singlish] could connect speakers across ethnic and socioeconomic divides like no other tongue could.”

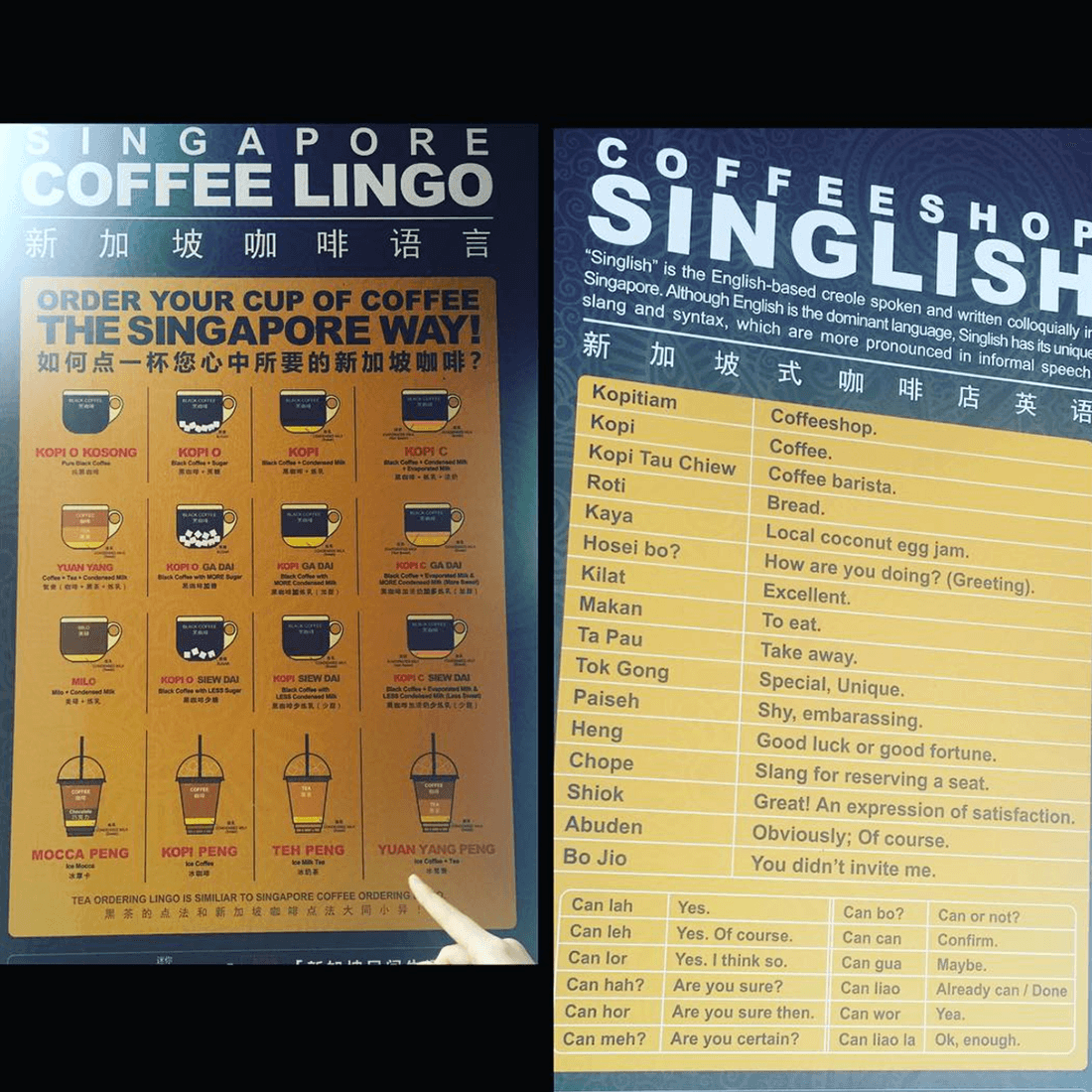

Singapore Coffee Lingo | Source: Nichaal Kaur/Instagram

Though not completely formalized, Singlish is a studied and codified language. There’s a Singlish Dictionary and Singlish poetry. Theatre, film, and music are starting to find ways of engaging with the language. The language is fun and expedient. One only needs to order a cup of coffee in a café to experience the playfulness and integration of Singlish. Coffee shops (or “kopitiam”) are an important aspect of Singaporean life. Even the word kopitiam is a portmanteau of the Malay “kopi” (coffee) and the Hokkien “tiam” (shop). When ordering a “kopi”, one specifies the strength (using Hokkien words), the sweetness (using Malay words), and the milk (using English abbreviations). The languages come together in a uniquely Singaporean way to serve a uniquely Singaporean purpose.

Borrowing the best bits of the parent languages, Singlish is efficient, dynamic, and playful.

Language as Suppression

Just as Singlish provides an opportunity to explore the creation of identity, it also gives a chance to witness an attempt at deleting an identity that is deemed “less than” by a political elite. Since 2000, the Singaporean government has been launching campaign after campaign to encourage its citizens to “Speak Good English.” The goals of these campaigns have been to stop the use of Singlish (seen as a broken, accented English by the government) and encourage the use of a standardized English. The campaigns use slogans, posters, competitions, and pop culture to convince the citizens to eschew their unique patois for the standardized tongue.

Source: Speak Good English Movement/Facebook

Rani Rubdy at the National University of Singapore claims that the Speak Good English movement constitute a “type of creative destruction in that it is a planned and deliberate attempt to root out Singlish before it takes complete hold of the speech community.” Rubdy argues that the movement is a “direct response to the dictates of globalization, subsuming, or more accurately, often compromising other priorities, preferences, and aspirations that the speech community may hold.” English is the language of global business, and as such, Singapore encourages the use of it to promote and manage economic success. While English does allow for ethnic harmony, it does not promote a unique social identity and consciousness. For the Singaporeans, only Singlish does that. Speaking Singlish enacts the full history of Singapore by embracing and combining the histories of colonialism and of diversity.

By speaking Singlish, the citizens are simultaneously engaging in the cultural practices of all ethno-linguistic groups within Singapore.

Source: Hafiz/Instagram

Why should the government suppress Singlish? Why not accept it is a unique language in its own right and promote a multilingualism among the already multilingual population? By enforcing “good” English, the government claims that their homegrown language is “bad.” By suppressing Singlish, the government risks suppressing the unique Singaporean national identity that has naturally emerged and grown since independence.

Reactions to these campaigns are mixed. Many Singaporeans recognize that Singlish comes off as slang, and so they avoid using the language in the workplace but will use Singlish at home or among friends. There are also many Singaporeans for whom English is foreign, and Singlish becomes an easy way to communicate across ethnic divides.

Language as Performative

Source: Ramøna/Instagram

These examples from Singapore show that speaking a particular language is a performative action. By engaging with that vocabulary, grammar, and syntax, one brings a particular identity into existence. Singaporeans who grow up speaking Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil at home enact their families’ culture when they speak their native languages. By speaking the language, they remember the history and connect with all who speak that language around the world. Those same Singaporeans then create a diverse Singapore when they speak Singlish in the market or English at work. By speaking Singlish, the citizens are simultaneously engaging in the cultural practices of all ethno-linguistic groups within Singapore. Rather than suppressing these cultural practices, speaking English allows Singaporeans to connect these cultures with a broader global community.

It is this performative ability of language that makes it so powerful and makes the government look for ways to control it. Lately, in the most recent Speak Good English campaigns, the government has been more focused on creating a distinction between Singlish and broken English. The government is starting to accept what Singlish speakers have been saying: Singaporeans code switch. They move from English to Singlish to their parents’ language, and they do so seamlessly. And it is that combination and multiplicity of performance that generates the truly unique Singaporean national identity.