ZACH BUSCH

You never love a dog quite like your first. Mine was named Rocket. “He’s a good dog,” my father always said. “A good dog deserves a good life.” When it was time, my father said to me, “A good dog deserves a good death.”

You know your dad means something to you when you start adopting his quirks, his ideas. You feel proud when you catch yourself in the act. You’re a night person because your dad never slept, and as a kid you’d stay up with him even when he told you not to. Lie awake in secret until you heard the door to his room slam shut. Just to learn what it was like being him. You drank your first coffee and your first beer to see what he tasted when he started or finished his day. You smoked your first cigarette to see what was so great that he always talked about quitting like it was the worst mistake he ever made.

We were a do-it-yourself kind of family, my dad and I, and we always liked to use our hands. I never chose to be a do-it-yourself guy, but I chose to be like my dad, which ends up the same.

So when Rocket got old and sick like dogs do, my dad helped me put it down. So I strangled the dog, or tried to — I was just a kid, and my hands were small. Rocket was bigger than me but frail, so it was a fair fight, and we wound up wrestling a bit and he left my arm bloody but couldn’t hold on. Dad said that was Rocket’s way of giving me a kiss goodbye, as best he knew how.

“Hurt comes from love,” he told me. “So does rage. The worst thing you can feel is nothing. Nothing is what happens when you forget to love.” In the end, Dad held his jaw shut and I stomped on his throat.

“Your eyes are red,” he said afterward, while he held me on the sofa. He handed me a gift-wrapped box. My first pair of aviators, just like his. “Don’t let them see.”

Source: Wikipedia

It wasn’t clean but it was a fight, and that’s what Dad said mattered. A good end to a good life. He died better than most dogs, Dad said. And that winter he read me The Call of the Wild and it became our bible.

I was eleven. A decade later, I told my father he should have waited until I was older. He lamented I should have been younger.

“In the world I see, we start early,” he said.

One morning, he told me to pack and we left Kingston before sunrise, heading north, weaving up along the Hudson coast. Like most Canadian boys, I had never gone far north, simply because no one did except the Inuit, and they had their own places to go. But I had always wondered.

Stepping out into nothingness, Dad took a look around, flipped open his favorite compass, and waited for me to do the same.

We settled up in Radisson, as far as we could drive, and in a freezer on the flatbed was the box with Rocket in it. Not that we needed a freezer up here. We drove off the trail and into a forest without footprints, and we buried him in the earth among birch trees. No coffin, just a shallow grave.

“Like nature intended,” Dad said. “Let’s pour one out for Rocket.”

He let loose a small stream from his flask. It crackled on the snow.

“We’re fourteen hours straight north from the nearest city,” he said, clapping me on the shoulder. “Perfect place for an adventure. We could do anything here.”

“You could hide something here,” I said.

“That’s right,” he said. “You could hide anything here.”

He handed me the flask. Irish coffee, mixed fresh — my first drink. “If this entire town disappeared, how long do you think it would take for anyone to know?”

I just shook my head. No idea.

“Long enough,” he said to me, and winked.

Radisson’s population was sparse and its cemetery was sparser. No one wanted to die old in the frozen nowhere. North of Radisson, the main road stops and no one really continues unless they have a snowmobile, or a plane.

My dad and I, we had one. We could go farther north than anyone else, and no one wanted to know where we went.

Until one day, when a scruffy older couple from town packed their bags and asked if they could come along. We let them build a hut a couple of miles from us, and we kept in touch. Humans need company. In time, we had a small but formidable settlement.

He called them settlers. When they said it, they sounded like they were smiling, like they were part of a secret club. But only Dad and I were explorers, on top of being settlers. I liked that we were special together.

“Did you know that most people are unhappy?” Dad told them over coffee one day, not for the first time. “It’s because we have nothing to do. You’ll understand when you start meeting people and they tell you about their job. Most of them don’t even know what their job is! That’s no way for a man to live. A real man knows his purpose.”

We kept our modest house in Kingston, but went about securing a bit of land up not far up from Radisson and we built a shack together, raised the wood around an old stove that frothed and foamed and raged against winter.

We hunted, first with rifles and later with bows. Ate them medium rare. Wore their hides in until they started to look fashionable.

A locked trunk in the back held enough “normal” clothing for when we drove back down. They were our costumes, Dad said. Our secret identities we used to make the world a better place. Like Batman and Robin.

When some settlers started bringing their families, we all built a schoolhouse together. In school we learned English, French, and a little Inuktitut. We had a teacher for writing, for math, for hunting, for history. We even had a rabbi. But Dad was the most important teacher, and he taught the grown-ups.

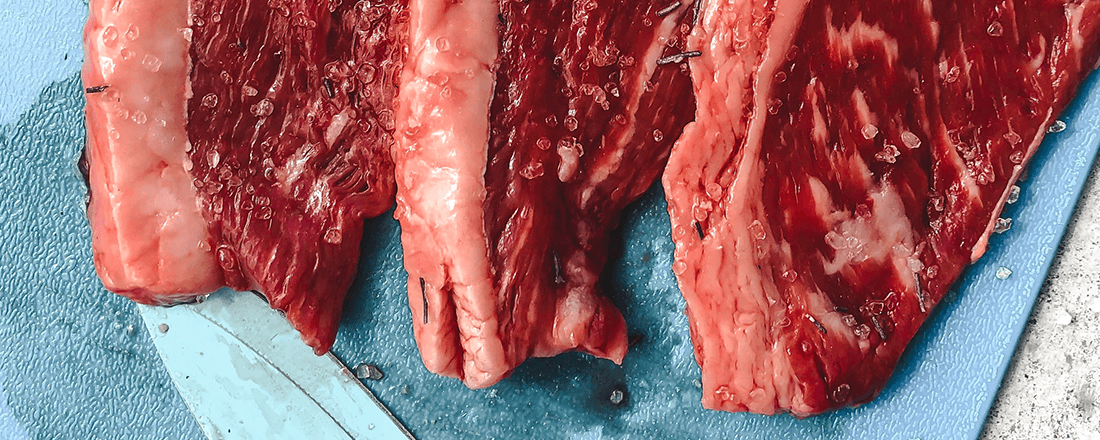

“Imagine for a moment that humans are a commodity,” Dad told the assembly one day. “That some alien master race came down and put us all in their zoos. They keep some of us for pets, some for study, some for amusement, but most of us for food. And some human meat is better than other human meat. They grade us like beef or chicken.

“So what makes good beef? Diet, for one thing. They have to be well fed. Nutrition. Then living conditions: are they comfortable? And then there’s slaughter. The way an animal is slaughtered isn’t just an ethical question or a matter of religious diet; it also affects the way it tastes. Texture, flavor. It’s all in the way it’s raised. Organically raised. Grass-fed. Free of hormones or additives of preservatives. Has a pasture to graze. Other cows to interact with. Lives the kind of life cows are supposed to have in nature. This is the premium beef, and it’s the best. Why? Because it’s taken from an animal the way God intended. A good life and a good death.

“Now picture luxury cuts of human in the supermarket. How do you raise free-range human? Does free-range human live in a concrete building and look at still images at a desk forty hours a week? Does it get its exercise on a little metal machine, in rows of other humans? No. That’s factory farming. That’s the meat they’d serve as McDonald’s.

“Free-range human lives in the wilderness, building what it needs. Its environment doesn’t have a thermostat, but neither does a pasture. Free-range human has space to run around and play. It gets exercise chasing its prey. It doesn’t sit in front of a TV all night; if you showed it one it would see a false idol. When locked in a metal box from 9 to 5, the human throws itself out a twelfth-story window rather than succumb to the madness of a desk job. Free-range human, true human, does not bear the weight of a lifetime of pent-up aggression; it kills until it is killed, and finds meaning in its struggle.

“In the new world, we will not allow ourselves to be farmed.”

At graduation, he hugged me and whispered in my ear, “Come find me when you’re ready.” Then he sent me on my way and handed me the keys to the Kingston house. His absence stung, which is how I knew I loved him.

I didn’t find out he was dead until too late. Death isn’t always on time, and we live better when we know we’re dying. My father always was a man who practiced what he preached.

The settlement had changed by then. It wasn’t a father-and-son business anymore, which meant there wasn’t much for me there. Now the dying, dead, and dead-inside flew in from all over the world. It wasn’t well-known, exactly, but it was well-known in the right circles, and if you asked around properly you’d end up in a truck going north of Radisson.

I met my ride at a rest stop a couple hours up from Montreal where no one would bother following or watching. Getting there was a real hassle.

He was alone, wearing a heavy jaw and tight eyebrows with little to hide. Smoking Reds but clearly new to smoking, and he drags too often. Right hand occupied, out of sight.

“Who am I taking?” he asked.

“Me,” I said. “Just me, and don’t you worry, no one saw it.”

“I’ll let you take these off once we get up far enough,” he said, handcuffing me into the passenger seat. “You try any funny business, I’ll fucking scalp you.”

“Don’t you know who I am?” I said.

“I reckon you want to die for some reason or other. That’s why they go up.”

“I’m there for the funeral. He was my father.”

“Oh.”

Fourteen hours is a long time to drive in silence.

Easily a hundred people sat around the central enclosure, and a maze of patchwork leather tents spread out farther back. Escapees, all of them.

A fire pit and a roasting spit.

I recognized and approached the rabbi, expecting an embrace. No such luck.

“You’re too late, son,” he said. “Funeral’s over. We missed you here, once.”

“How did he die?” I asked.

“Not the way he wanted,” he said.

We walked closer. The man on the spit had died recently and frozen. Flesh just lightly singed. Thawed.

“Is that really enough to feed all these people?” I asked. It was the only thing I could get out between my numb lips.

“You don’t fill up on wine and wafers, do you? It’s not to make you full.”

Closer, and I can almost make out Dad’s crooked nose. Its skin cracked from cold, softened again with heat. Its flank had already been cut into, generously.

“All this way, just for a meal,” I said. “Does someone choose my cut or do I?”

He looked at me as if I were a naked beggar, uninvited and not even courteous enough to dress up.

“You don’t get a cut,” he said. “You don’t get to eat here. Didn’t you hear? Your father died of cancer. Alone, defeated. Our leader. Just waiting, hoping you would arrive. Do you know what that was like? After he gave good deaths to so many of us, he died in a sick bed. Our finest hunters and fighters offered to do it for him. But he wanted you, and you didn’t come.”

“I didn’t know,” I said. “He said I should come back when I was ready.”

“You left us,” he said. “A father’s proudest achievement is raising a son who is better than him. He wanted you to do it, because it would have meant success. Instead, you abandoned us. For what? To raise your child in a factory? Our people have died enough unnatural deaths. Now go home.”

I said nothing because he had said it already. On my way to the gate, I stopped by the old cabin where it started. Rocket’s icy eyes met mine from above the fireplace. The worst thing you can feel is nothing.