I am getting deeply exhausted by the idea that we live in a “uniquely” political time; that we as an epoch are somehow worse at getting along or better at picking fights. At a global level, there is less violence in the world year after year. Within the U.S. more people are enfranchised every year. I believe we are moving — slowly, unevenly, but consistently — towards eradicating structural injustice. A narrative which centers our disfunction, which posits Republicans and Democrats as inherently and unavoidably distinct types of people, does not help us. How could it?

At the same time, there is good research documenting the growth of inter-party distaste. There is good research pointing out growing socioeconomic inequality, and the disparate impact of the heroin epidemic. There is good research showing a post-Trump resurgence of violence and hatred directed against minority communities.

So, how can I square the circle? How can I promote a constructive narrative that also acknowledges the state of the world? Enter Hecht’s article. It delightfully acknowledges idiosyncrasy in the American political story. It avoids unifying myths, and points out how “now” is not unique — “now” is the result of “then,” and the two will come together to predict “later.” The combination of history, insight, and just a touch of cynicism is a welcome relief. It is a relief from maps of blue and red, from discussion of a world fundamentally bifurcated by boundaries that, Hecht points out, are themselves accidents of history.

DAVID HECHT

The Constitution is the founding document of the United States we know today. Yet there are over 200 years of subsequent legal history that can attest to the blind spots in the Framers’ text. The boundaries creating and separating states is no exception. Article 4 Section 3 briefly addresses how a territory becomes a state:

“New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

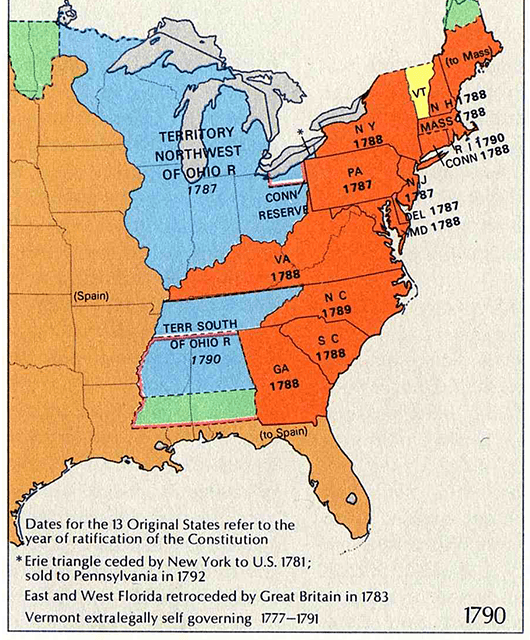

Map of the 13 Colonies | Source: National Atlas of the United States/Wikimedia Commons

Congress creates states out of thin air, inventing immutable borders with the stroke of a pen. Obviously omitted is how the to-be-formed state’s borders should be created, or what should happen in the event of a dispute between states. Also unaddressed are the borders of the 13 states that would be ratifying the Constitution, not to mention how they got their boundaries in the first place. It is not in the Constitution that the United States’ internal borders are found. Rather it is stories such as shifting pre-Constitution boundaries, resolute squatters, and legal principles of the times that create the absolute lines that divide the United States.

Virginia

When Columbus “discovered” the Americas, Europe’s mercantilist economic principles of the time held that the best economic strategy was to produce the most and the best goods in a closed, internal system, use those goods to create trade surpluses to benefit the mother country, and ultimately collect massive piles of gold. Lands of riches and wonders really helped to achieve those aims, especially if the rumors were true that there was a literal city of gold in the Americas. Thus, claiming and seizing the “new” land quickly became the order of the day, even as people weren’t 100% clear on what they were claiming and seizing, from whom they were claiming and seizing it, and who else might be claiming or seizing the exact same thing. There was no authority regulating these claims and seizures, and countries felt no reason — legal, practical, or moral — to limit them in any way (the exception to the lack of authority was the Pope in matters between Spain and Portugal through the papal bull Aeterni regis and the subsequent Treaty of Tordesillas).

It is in this environment of claiming, seizing, and disregarding the rights of any former residents that the colony of Virginia was chartered in 1606. This charter attempts to regulate “habitacion, plantacion and to deduce a colonie of sondrie of our people into that parte of America commonly called Virginia,” but it (obviously?) did not age well. Three years later came a major edit, replacing the claim’s “100 miles inland” limit with an intentionally vague “sea to sea” provision, all while nobody had any idea how far away that second sea was. Though nobody at the time knew it, Virginia was now a colossus.

1606 Map of Virginia | Source: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

This gargantuan Virginia wouldn’t last. More and more land in North America was chartered by various English Monarchs to pay back various debts and favors, and most of the land necessarily came out of this first colony. After the American Revolution, Virginia was restricted by the 12 other states, and the eventual settlement with England recognized the Canadian border and the Mississippi river as the United States’ northern and western borders. Virginia was still the biggest and most powerful state of the 13, but it was much reduced from its sea to sea beginnings.

It is stories such as shifting pre-Constitution boundaries, resolute squatters, and legal principles of the times that create the absolute lines that divide the United States.

Included in Virginia’s 1783 borders are the future states of Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. Among the many differences such a Virginia would cause today is that we presumably wouldn’t have the Rust Belt; all of it would just be upstate Virginia. But this enormity rankled the other states. Virginia was already the most powerful and most populous among them, and the westward expansion that was already underway would only make that problem worse. This conflict proved a significant obstacle for the harmony among the states in the early republic. It was the creation of a document that would try — poorly — to regulate the admission of new states that would next trim Virginia down. The nationwide adoption of the Constitution brought with it a compromise in which Virginia ceded all of its land north of the Ohio river via the Northwest Ordinance, losing everything but West Virginia and Kentucky in the process. After going from the vast majority of North America to a relatively narrow strip between the Atlantic ocean and Mississippi river, Virginia was done ceding land to non-Virginian interests.

However, Virginia was not done ceding land to internal interests. The very Virginians who moved into and settled the area that would become Kentucky quickly became disenchanted with the government back east, from which they were geographically and economically removed. Soon Kentuckians were clamoring for independence. After ten conventions that petitioned for such from both Virginia and the United States government, the Virginia legislature relented. Once more the state shrunk.

1792 Map of Kentucky | Source: Antique Prints Blog

The final reduction of Virginia’s borders came during the Civil War, when a geographically isolated group of Virginians called themselves “West Virginians” and joined the Union instead of the Confederacy. Beginning as a majority-of-a-continent-sized colony granted by the English crown, it relinquished land to the crown, to its fellow insubordinate colonies-turned-states, and to portions of its own wayward population. Virginia’s borders have been modified by intention and accident, with precision and vagary, via both mandate and populism: far from absolute, they are a mishmash of circumstances of the times, with the only constant being reduction. Even the Constitution’s declaration that “no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State” cannot prevent the last two reductions to Virginia.

[When] the Supreme Court must use the document to resolve such conflict, it is bizarre legal theory that ultimately determines the issue.

Vermont

Virginia would not be the first state to have a front row seat to this clause of the Constitution being outright contradicted. It would only be one year after the Constitution was ratified by the final state (Rhode Island) that the rules of state creation would be subverted.

A more militant and decentralized boundary creation can be seen in the New Hampshire Grants — known today as Vermont. The area was composed of approximately 135 land grants given out by the New Hampshire governor, Benning Wentworth, starting in 1749. Wentworth chose to assume a generous reading of the colony’s Western boundary and sell land that was actually part of New York. Because New York colonization was mostly contained to the Hudson Valley at this time, the grant-holders moved right in, American Indian residents be damned. New York appealed to King George to resolve this dispute, and he ruled in their favor. Unfortunately for New York, the pro-Vermonters established militias were not the sort of people who would listen to King George without a fight. After some relatively organized mob justice, the members of the prominent militia The Green Mountain Boys were all on New York’s most wanted list. Their leader, Ethan Allen, was telling people whose cabin he had just burned: “God damn your Governor, Laws, King, Council, and Assembly.” These were fighting words, so it was a good thing a huge revolt was about to break out across the continent.

It is not at all unusual for borders between nations to be decided by force.

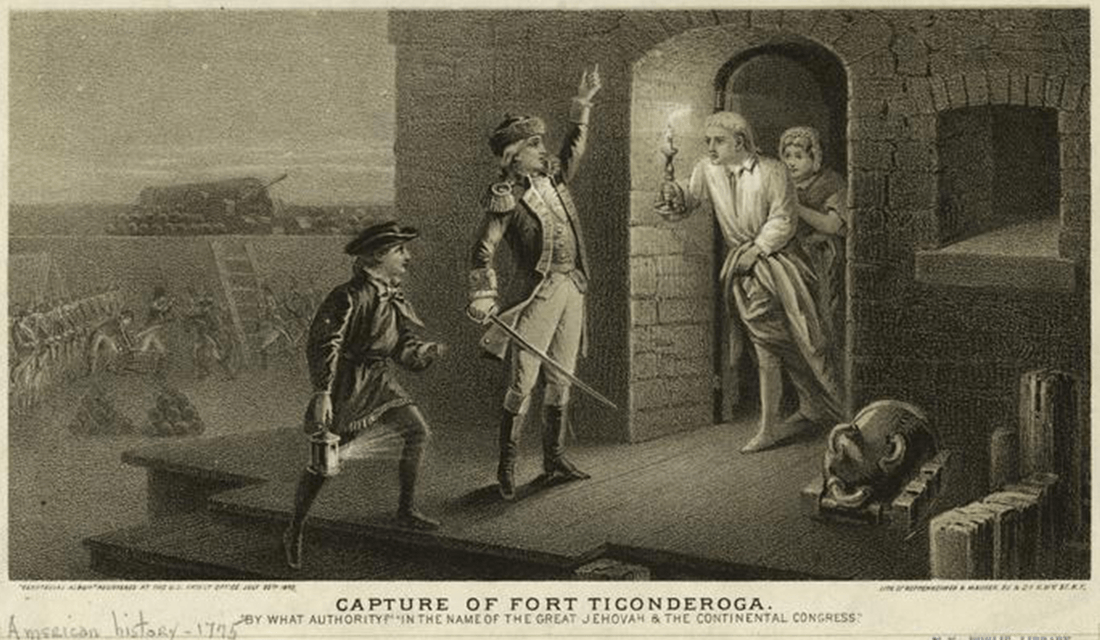

The Revolutionary War began before the Second Continental Congress declared independence, and in the leadup, each side attempted to gain control of various caches of weapons before the other could do the same. One such store was in the middle of northeastern New York near our bunch of militant squatters, at the under-garrisoned Fort Ticonderoga. A fairly disjointed combination of militiamen and the Green Mountain Boys went to take the fort, accompanied by Massachusetts-deputized Benedict Arnold. Despite this motley crew, everyone wanted the same thing, so internal conflict was avoided and the Fort was taken easily. In a militant frontiersman’s dream come true, the fort contained more weaponry that expected, as well as a considerable amount of booze. After some contentious disputes that involved guns, Arnold secured most of the weapons and sent them to Massachusetts. There they were used to fortify Dorchester Heights, and the British were forced to evacuate Boston. This was a good result for the colonies, but it was also a little awkward: New York’s legislature had no idea the Ticonderoga operation was even happening. This was bad — it was in New York — and worse; a group they considered wanton outlaws were among its heroes.

1875 Engraving of the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Ethan Allen on May 10, 1775 | Source: New York Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

To review, there were a bunch of guys who purchased land from someone who didn’t really have a right to sell it. They are fighting the state that technically owns the land. They’re fighting the British even harder. To do so, they’re venturing into areas that even they would admit are part of New York. While the Revolutionary War did impart an “enemy of my enemy” mindset to a degree, New York (and to a lesser extent New Hampshire) blackballed Vermont’s drive for statehood in congress. This forced those 135-ish New Hampshire Grants to become an independent Vermont, economically isolated from both England and the United States. It wasn’t until 1790 that the New York legislature relented and agreed to allow Wentworth’s squatters to become the 14th state the next year. Previewing the process that would soon lead to Kentucky’s break from Virginia, Vermont departed from New York and New Hampshire, in this instance with a significantly more contentious and violent prelude. The boundaries of Vermont directly contradict the constitution, that “no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State.” They exist because of a mindset, best exemplified in the last stanza of the 1779 poem The Song of the Vermonters by John Greenleaf Whittier:

Come York or come Hampshire, come traitors or knaves,

If ye rule o’er our land ye shall rule o’er our graves;

Our vow is recorded — our banner unfurled,

In the name of Vermont we defy all the world!

Cherokee

It is important to remember that the Virginians, the Vermonters, and all the other European and European descendants colonizing the Americas were doing so at the expense of hundreds of diverse and distinct native peoples. These peoples — those who weren’t among the approximately 90% who died of smallpox — responded to European encroachment in a multitude of ways.

A Sick Native American | Source: National Library of Medicine/Wikimedia Commons

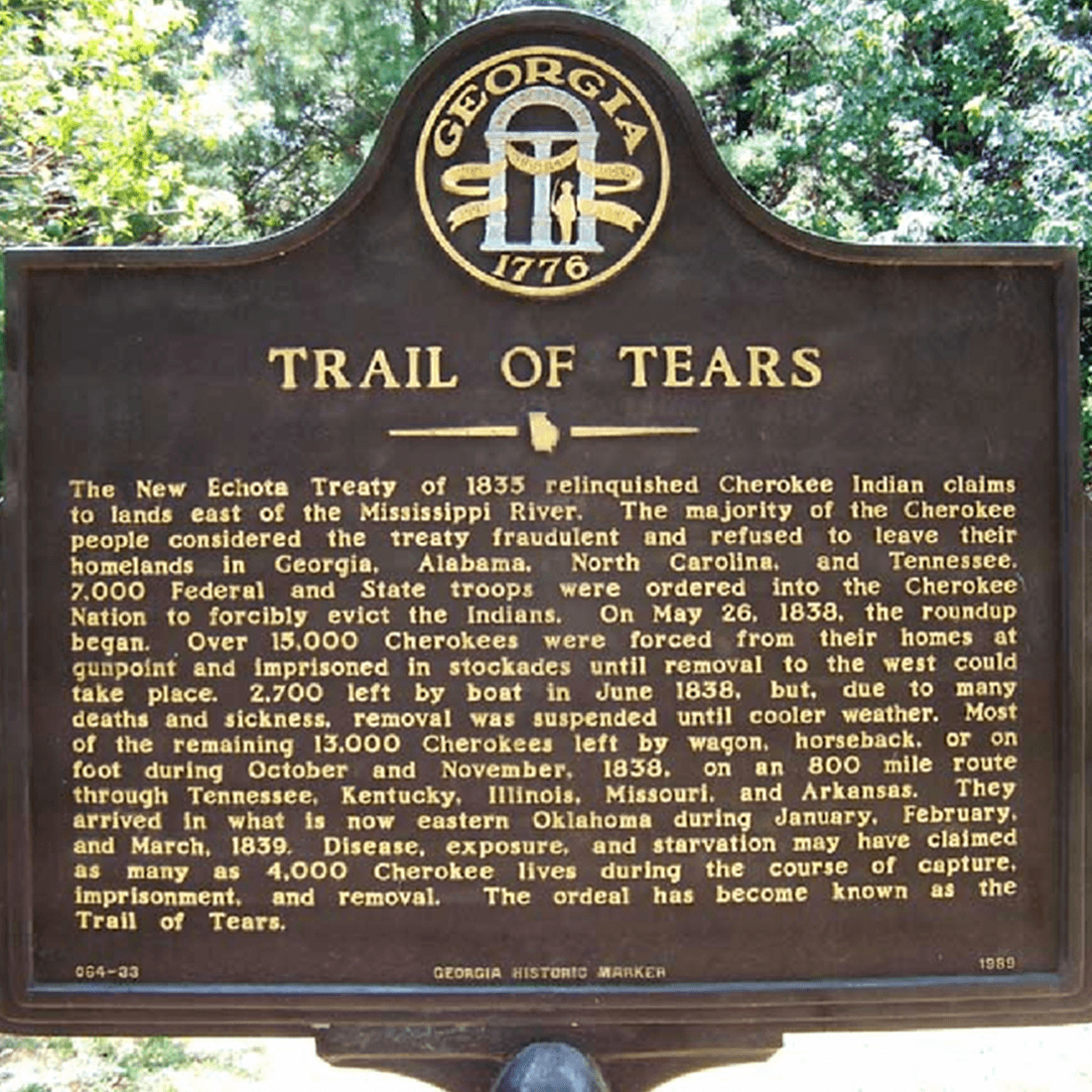

The Cherokee were on the forefront of embracing “civilization” initiatives implemented by these early settlers, which were basically attempts at getting American Indian society to more closely resemble the society of Europeans. The Cherokee adopted representative government, yeoman farming, and even created their own written language from scratch. They produced a written constitution modelled after the United States Constitution. They negotiated treaties with the United States government that firmly established territorial borders. This assimilation eventually came to irk the government of Georgia and the 7th president of the United States, Andrew Jackson. You see, in the decades since those treaties were signed, the population of Georgia had grown and the state viewed more American Indian land as the best place to house that population, treaties notwithstanding. Between 1827 and 1831, the Georgia legislature passed increasingly powerful laws to exert unilateral state control over the still-independent Cherokee lands. In a nation-level parallel to Georgia’s actions, Andrew Jackson was elected president on a campaign of id, umbrage, and sending native peoples to the other side of the Mississippi river. Congress subsequently passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, and land seizure was all set to go. But of course, the same Cherokee leaders who put stock in treaties, representative government, and written constitutions realized all of these actions might be illegal. In 1831, the Supreme Court agreed: native treaty land rights had the protection of the law. Unfortunately for the Cherokee Nation and general human decency, the Supreme Court does not have an army to protect its ruling. Andrew Jackson did, and he used it to forcibly resettle the Cherokee people, killing vast numbers along the way.

Trail of Tears Sign | Source: Channelview Independent School District

It is not at all unusual for borders between nations to be decided by force. The vast majority of lines we see on a map today were determined either by war or by more powerful nations dividing spoils post war (e.g. Britain and France carefully and deliberately creating countries in the Middle East after World War I to ensure that traditional ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences wouldn’t be mashed together like a three-meat sausage). The Cherokee case is unusual because this process was conducted internally in direct opposition to the nation’s highest law. Where in Vermont it was the extralegal pigheadedness of the squatters that created the boundaries, in the case of the Cherokee it was similar illegal pigheadedness that doomed them and sent their former borders to the dustbin of history. The Constitution — the document intended to protect the rights of people living in the United States — was rendered toothless. The borders and jurisdictions the Supreme Court defended proved to be mere lines in the sand.

Georgia v. South Carolina (1990)

Despite the case studies from above, the majority of territorial disputes in the United States’s history have been between two states, and the Supreme Court has effectively served as the final arbiter. Of this body of cases, Georgia v. South Carolina (1990) stands out. The case comes from a territorial dispute within the Savannah river between the two states. New islands appeared in the river on the South Carolina side of the dividing line through mostly natural means, but the previous division had given all islands to Georgia. The area in dispute contained rich natural resources and oceanfront property, raising the stakes. In simple terms, Georgia argued that the islands were Georgian because the “island” clause was preeminent, while South Carolina claimed the islands were South Carolinian because the line mattered most.

This dispute stands out because of the rulings of the Justices. Five separate opinions were written: one with a three-judge plurality, and four dissenting opinions with two Justices on each (Justices can write their own dissent and sign another person’s dissent on the same opinion). Chief Justice Rehnquist — perhaps realizing the opinion’s farcical nature — was in the minority who neither supported the opinion nor wrote their own disagreement.

Case opinions

Plurality: Justice Blackmun, joined by O’Connor & Brennan

Dissent: Justice Stevens, joined by Scalia

Dissent: Justice White, joined by Marshall

Dissent: Justice Scalia, joined by Kennedy

Dissent: Justice Kennedy, joined by Rehnquist

Many of the dissents are regarding one or another part of the ruling, such as agreeing along with the river section but not the ocean section or vice versa. The principle that ended up holding the day was acquiescence. I am not a legal scholar, but my understanding of acquiescence is that when one’s rights are unknowingly infringed upon, and then that individual doesn’t raise an objection in a reasonable amount of time, those infringed rights are forfeit. For instance, let’s say I leave a ladder outside between my house and my neighbor’s, and then forgot about it. My neighbor sees it and she thinks, “Sweet, free ladder!”, never once considering it could be mine. She then proceeds to use it frequently. I rarely use my ladder, usually keeping it in the back of the garage, assuming it’s always there. Then one day, five years later, I finally see my neighbor using my ladder. Acquiescence would dictate that the ladder is no longer mine. Had the Vermonters been a less rowdy group who actually submitted to the rule of law, this argument would have been an appropriate one for them to use. Of course, the Cherokee immediately objected to their rights and lands being trampled, and look what good it did them.

In Georgia v. South Carolina, the islands were Georgia’s ladder. South Carolina gave the islands a makeover, expanding them, developing them with luxury property, and then taxing said property. When Georgia finally got around to realizing what South Carolina had done, they had already given up their rights to the islands. A different analogy might be my neighbor planting an avocado tree in my yard, watering it, pruning it, and after ten years finally harvesting avocados from it — all while I don’t say word one about this tree. Those are, apparently, her avocados. The Constitution provides scant basis for any resolution to cases of conflict between states. Thus, when the Supreme Court must use the document to resolve such conflict, it is bizarre legal theory that ultimately determines the issue. Unlike the previous Supreme Court ruling against Georgia, this time the state abided by the decision.

Savannah River Today | Source: Debs/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0)

The United States presents itself as a unified and absolute whole — standing together as one nation, not fifty states. Yet when it comes to determining the boundaries of those very states, it is clear no absolute law or arbiter exists. The Constitution is some combination of vague and irrelevant on most disputes, and so entropy, persistence, pigheadedness, and bizarre legal theory are proven to be the determinants of the boundaries that divide the states of the United States. These boundaries are determined by whatever means that ruled the day at the time. When they eventually are determined, the uncertainty, arbitrariness, and alternative lines are lost to everything but cartography. The borders of the United States seem finite and absolute, but the creation of them — and the changing of them — is haphazard and adaptable by whoever has the will and power to do so.