SAM SCHANWALD

DISCLAIMER: The following piece contains discussion, links, and images that are of mature content.

I.

In his The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, sociologist Erving Goffman suggests “we are all just actors trying to control and manage our public image.” If he’s correct, then the public structures we surround ourselves with are crafted scenic designs for those lifelong performances. Within the scenic design that supports our daily plays, there are pieces of architecture meant to create prescribed physical and psychological traffic patterns. These structures, both public and private, induce repetitive choreography that upholds community ideologies, calm and comfort, encourage mating dances, and so on. They include turnstiles and rotating doors and billboards and, of course, murals.

Goffman proposed a dramaturgical model for understanding public (onstage) and private (offstage) human behavior. In doing so, he thereby illustrated a binary of behavior, separating that which takes place in the dressing room from that which occurs in front of an audience.

Our lives’ scenic designs, on the other hand, cannot be separated into public and private in the same way. Though how we individually act certainly varies based on whom we perform for or whether we perform at all, the ways in which the scenic design shapes our performances are embedded in both our on- and offstage environments. The interior decoration of a bedroom, though private, communicates a personal philosophy about how the space should prepare the actor to enter the public sphere again. So, even after the public performance habits and physical tailoring are cut away, the space still holds stimuli that remind us how we must inevitably re-enter the public sphere. We put particular books on the nightstand hoping a sexy bedmate, whom we must impress at all costs, notices them. We model our bathrooms after public notions about hygiene aesthetics from the 1950’s. Private home bathrooms begin to look like tiled and sanitized airport loos.

Real life’s scenic designs’ blurring of private and public works inversely, too. The aforementioned examples show how we, consciously or not, haul staples of public life into our private lives. That commixture of public and private in a physical space is not dissimilar from an actor’s posting an inspirational quote on her mirror to inspire a certain mindset, easing her into a demanding performance. But, the relationship between public and private influences is reciprocal. Just as we haul public into private, private also manifests in the onstage world in unexpected ways.

Let’s dig into the reciprocity of public and private psychological spatial relationships through a particularly insightful scenic design convention: dicks painted on walls.

II.

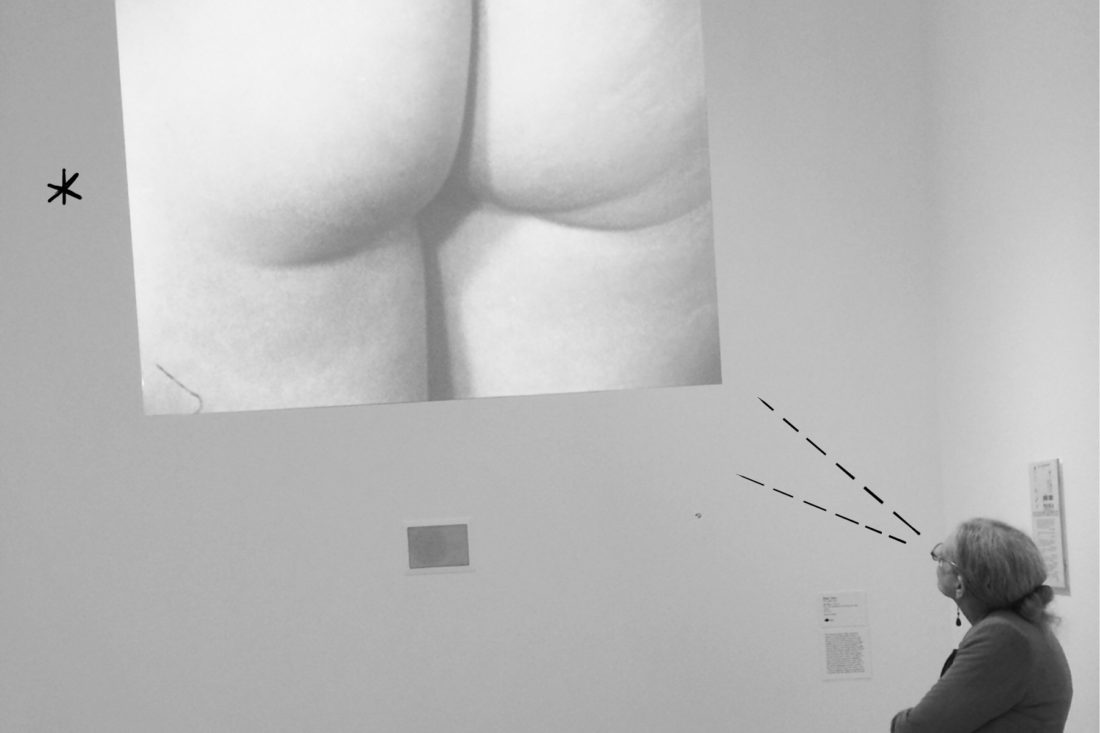

How can we begin to explore the rift between the privatization of genitals and phallic imagery’s prominence in public art? It’s a seemingly impenetrable paradox: that private parts should be kept behind zipped jeans, yet penises in public art embody some sort of desirable aesthetic, permissible in the public realm so long as they appear in an artistic context.

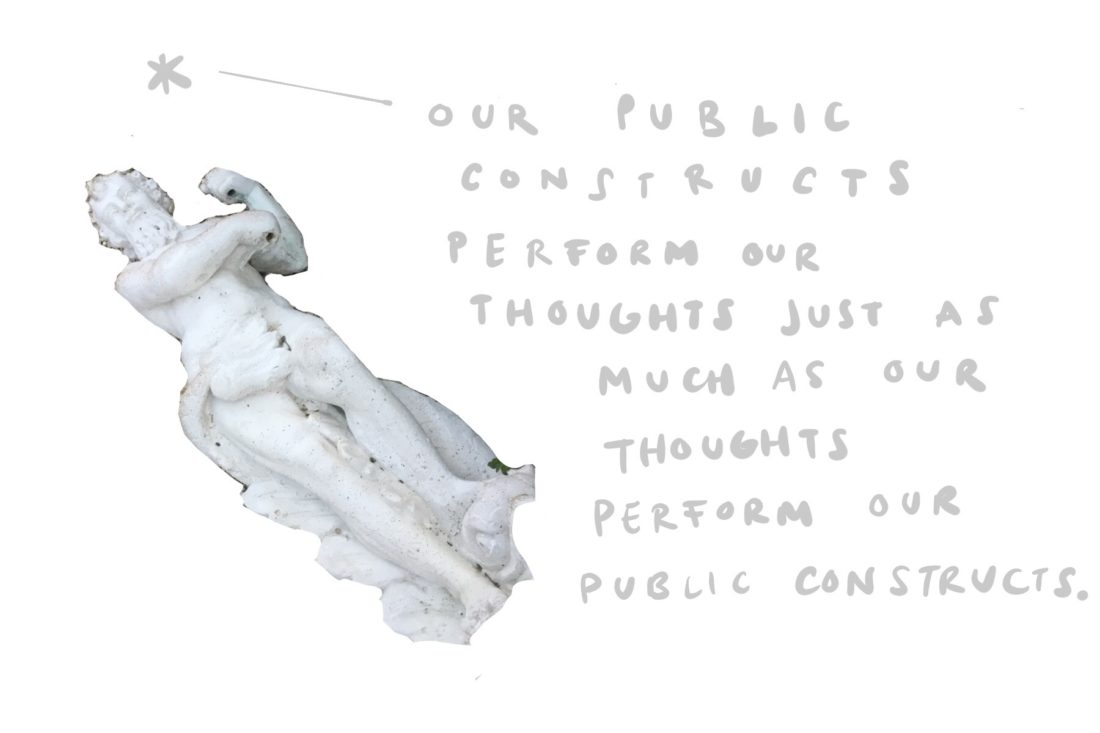

Our public constructs perform our thoughts just as much as our thoughts perform our public constructs.

Super recently, director Jill Soloway’s response to Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick made waves for bringing a story about phallic haunting to online television junkies. In Soloway’s series, which takes place at an artist’s retreat in Marfa, Texas, women and men alike seem to be mysteriously governed by the masculine endowment of one titular Dick, who leads the retreat. His public sculptures, Christo-esque in scale, stand erect in the middle of open Texan plains. Subtle monuments to a phallic undercurrent that pervades life in this isolated and hypersexual town (the main inhabitants of which are artists), they raise a question about the relationship between public structures and private consciousness.

Do the phallic sculptures simply reveal a pre-existing facet of our shared collective consciousness, or do they actually subliminally shape the minds of Marfa, inducing dick-obsessed fits?

The same question can be raised in regard to the hypersexual murals lining the walls of salles de garde in numerous French hospitals. Many salles de garde — or lounge rooms for medical interns and students — host floor-to-ceiling carnivals of painted genitals. The history of these murals is certainly an underground one, but we know that both men and women are involved in the creation of them, and also that the paintings are intertwined with initiation rites for medical students. In one particular mural, a male member stands erect center stage, shooting pink and yellow ejaculate. Though anatomical diagrams in a medical facility are certainly expected, the large-scale pornographic frescos seem misplaced.

Perhaps we owe the birth of these psychosexual murals to the high-stress climate of medical school. Perhaps the act of painting them is meant to depressurize the demands of medical school and nursing apprenticeships. Perhaps the orgiastic art is meant to quicken the pulse of the hospital staffers.

Whatever the case, it’s undeniable that the shared mural must reflect a deep-seated fiber of a group’s collective inner psychology. These phallus murals make an abstract private yearning architecturally concrete. And again, we ask, who is the metaphorical commissioner of the salles de garde paintings: the pre-existing internal phallic obsession or the pre-existing external pressures of tradition?

Just as we haul public into private, private also manifests in the onstage world in unexpected ways.

In a public bathroom in 1989 New York City, painter Keith Haring performs an act of alchemy. Scrawling out vignettes of gyrating queers, he conjures nostalgia for a juicy masculine eroticism, one that AIDS crisis anxieties crushed. His mural, Once Upon a Time, is the erotic equivalent of an astronaut looking back at his tiny blue dot. He has nothing to measure how far into the isolated abyss he’s ventured aside from an unignorable feeling of loss and the unignorable death toll (which will soon reach 100,000). He remembers the home planet as a sensually lit room sans neuroticism and fear: a place before the notion of sexual quarantine existed. He remembers it as a place where true skin pores trumped impervious latex.

He doesn’t know that his work of entangled penises and translucent body liquids will

become an iconic piece of the meticulously preserved NYC gay landscape. After over

twenty years of wear and paint chipping, the mural received a facelift from a skilled

mural conservator and a subsequent reopening in 2012. We have an unlisted donor to

thank for the work that went into the mural’s preservation, but we have NYC’s LGBT

Community Center to thank for fomenting the mural’s cultural importance.

Haring didn’t know that his celebration of our sexually deviant community would

become a visual relic of perseverance. He doesn’t know that the mural adorns a four-

walled breeding ground for the disease that will ultimately kill him.

It’s a revolutionary act: to dance while bleeding.

Haring’s iconic penis-ridden bathroom mural counteracts public anxieties about gay sex by showcasing stigmatized private acts. By Haring’s example, we begin to think about public artwork as simultaneously responding to our collective consciousness, and as a potential shaper of buried desires of our private lives.

III.

We must necessarily understand the relationship between public and private as wholly reciprocal. If life’s architecture is a curated scenic design that exists both in- and outdoors, then it’s clear that the wall between public and private is porous. In the case of how spaces shape us and how we shape our spaces, it might be argued that there is no useful division at all.

Our public constructs perform our thoughts just as much as our thoughts perform our public constructs.

The challenge, therefore, is this: to create public art that not only collectively invites us in, but also thinks deeply about how a long-term public installation continues to shape its community’s consciousness.

All illustrations by Sam Schanwald.