NORA ROSENGARTEN

In this issue, we talk to Brendan Quinn, a law clerk whose interests include intellectual property and food & beverage regulation. Brendan and I first met in college, where our friendship blossomed through collaborations in theatre. In the years since, we’ve gone down different paths — I’m in graduate school for art history, and Brendan received his JD earlier this year. Perhaps it is because what we do in our respective careers is so different that I am endlessly fascinated by his thoughts and knowledge about law and legal structures; some of which he has written about previously in a previous issue of SixByEight Press. For this issue, we sat down with Brendan to ask him, as a former winery employee and student of law: what are the laws around alcohol? How is alcohol regulated? What do these regulations communicate?

Hi Brendan, thanks for making the time to do this interview!

How did you first get involved in the world of wine and alcohol?

Brendan Quinn

After I graduated from college, I moved back home to Long Island. I didn’t realize this while growing up there, but the East End of Long Island is a sizable wine region with around thirty vineyards. I knew I had a year before I started law school, so I got a job working at one of these vineyards, Paumanok Vineyards, where I learned a lot about growing grapes, making wine, and the wine industry itself. As someone whose prior understanding of wine consisted of almost exclusively Barefoot Sauvignon Blanc, my eyes were opened to the intricacies and complexities of this product and the industry around it.

What prompted your move from former winery employee to potential “wine lawyer”?

Brendan Quinn

While I was working at the vineyard, during conversations I would tell customers that I planned to go to law school and practice law. A customer once told me, “You should practice wine law.” And my response was “Huh? What even is that? What would that entail?” It never occurred to me that this was something a lawyer could be involved with. I did some research and learned that there are, in fact, numerous laws that regulate the production, distribution, advertising, and sale of wine and other alcohol beverages. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that this was an area of the law that I might be interested in exploring further.

Can you talk a little about the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and what made you decide to intern there?

Brendan Quinn

When I got to Georgetown Law, I began to consider where I would work the summer after my first year. I knew I wanted to stay in Washington, D.C. and intern with a government agency, which still left open an enormous amount of possibilities.

I figured that my first legal internship would be a great opportunity for me to do something out of the box, so I just decided, “I’m going to find the federal agency in charge of regulating alcohol.” I figured it out, applied, and was fortunate to receive a position. The agency [turned out to be] the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), and it is a small agency within the umbrella of the Treasury Department. A lot of alcohol regulation is done at the state level as a result of the 21st Amendment, but there are also important federal laws and regulations which apply to alcohol as well. There is a lot of overlap between the states and the federal government, but, generally speaking, TTB regulates alcohol that moves in interstate or foreign commerce with a focus on collecting federal excise tax, regulating how producers manufacture alcohol through distillation or fermentation, pre-clearing alcohol labels and advertisements, and overseeing the commercial practices of the alcohol industry.

Why the Treasury Department? Why not something like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)?

Great question. Exactly which federal agency has regulated alcohol has shifted throughout history, but alcohol has usually fallen under the umbrella of the Treasury Department since at least the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAAA) in 1935, passed in response to the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1933. Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) predates all this, historically, alcohol was viewed more as a imminently taxable “vice” product than it was as a “food” or “drug,” so the Treasury (i.e., the agency collecting the taxes) got the responsibility. Today, alcohol is technically regulated more like a “food,” but it also a “drug” and has all the basic qualities of other drugs that are either illegal or fall under the purview of the FDA. As a result, alcohol can sometimes occupy a regulatory gray space between the FDA and TTB.

Why is alcohol regulated as a food, and not as a drug?

Brendan Quinn

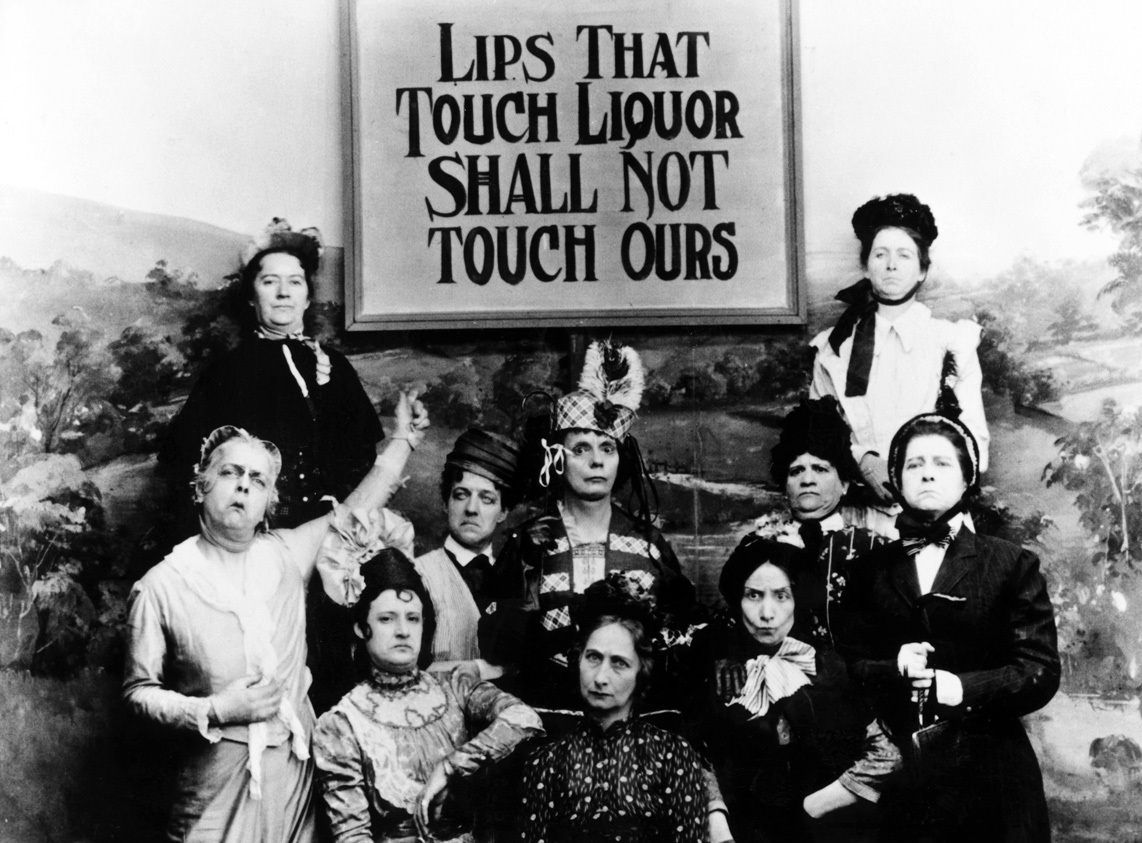

I think it’s related to alcohol’s historical role in society and culture. Our awareness of the long-term health consequences of alcohol on the brain and on cognition are relatively modern, tracking the development of modern medicine. Historically, social movements — like the Temperance movement — that opposed alcohol were more concerned with the spiritual, moral, and societal problems linked to alcohol consumption than they were with the biological effects on any one individual consumer. The modern understanding of alcohol certainly is more aligned with the modern definition of a “drug,” but that understanding today is not the same as it was two hundred or even one hundred years ago.

Still from the 1901 movie Kansas Saloon Smashers satirizing woman teetotalers | Source: Wikimedia Commons

I know this isn’t your area of expertise, but I’m wondering: how is tobacco regulated?

Brendan Quinn

On TTB’s end at least, in general, TTB regulates all the taxation and permitting aspects of the manufacturing, importation, and exportation of tobacco products.

Beyond TTB, tobacco products were not really regulated comprehensively at the federal level until the late 1990’s, when the FDA more aggressively asserted their authority over tobacco products by claiming they were “drugs” or “devices.” The tobacco industry wasn’t pleased and there ended up being a big U.S. Supreme Court showdown in a case called FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. in 2000. The Supreme Court ruled that tobacco products were not “drugs” or “devices” within the meaning of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the law that gives the FDA most of its power), so FDA could not regulate tobacco products. All was not lost, because this decision was overridden by Congress in 2009 by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which explicitly gave FDA the power to regulate tobacco products.

One thing that is interesting about having one institution regulate both alcohol and tobacco is that, in my mind, the stigma around consuming alcohol — while not informed by the kind of scientific research we have today — is much older than the stigma around smoking.

I agree with you on that. I think it’s because alcohol has more easily apparent negative consequences — you drink, you get drunk, your speech gets slurred, your cognition slows down, your motor skills worsen, your mood becomes more unpredictable, etc.

c. 1830-1840 drawing titled Alcohol, Death, and the Devil by George Cruikshank | Source: Library of Congress

When excessive drinking continues and reaches the level of addiction/alcoholism, there can come along the personality changes and interpersonal problems that everyone recognizes with long-term alcohol dependency. People experience the negative consequences of alcohol more readily. On the other hand, apart from the smell, you don’t experience the negative consequences from tobacco until much later down the line, when years of smoking have contributed to an increase in cancer risk or cancer itself. Remember that it wasn’t until the 1960’s that the federal government even figured out and admitted that smoking caused lung cancer! That’s the primary reason why the stigma against smoking is so much newer than the stigma against alcohol.

How does the history of alcohol in our country play into these regulations? I guess what I’m curious about is what is the legal history of alcohol in the United States?

Brendan Quinn

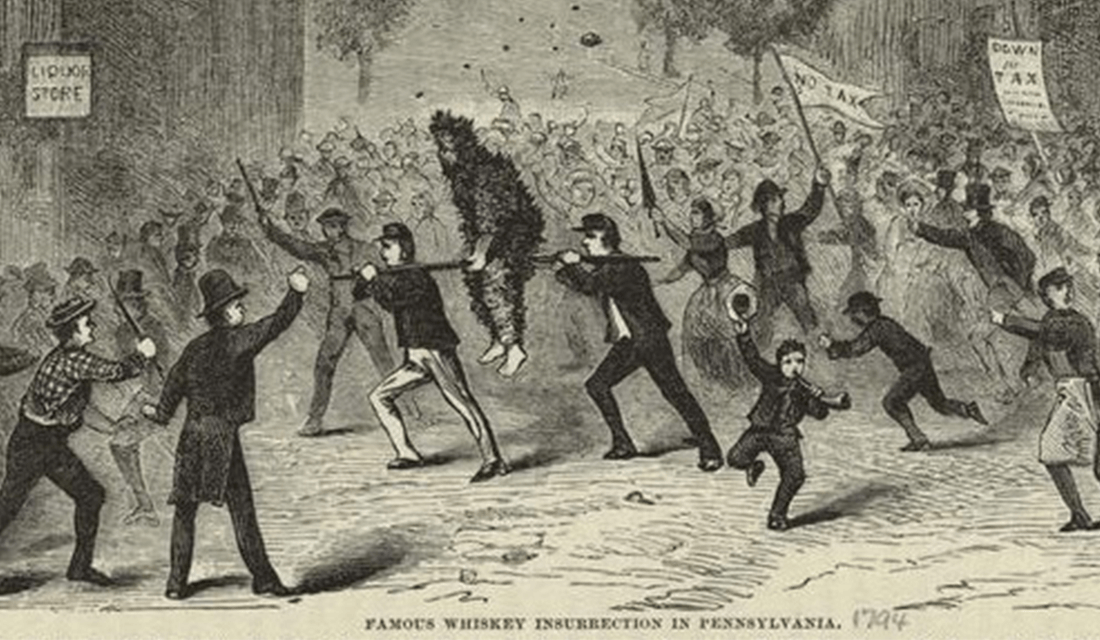

I think I’ll start with the history because it’s helpful to understand how it’s regulated. Alcohol in American history goes back basically to the founding of the country (in my condensed version) — the first real challenge to federal authority after the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1789 was the Whiskey Rebellion (1791-1794).

To simplify, to pay back accrued Revolutionary War debts, Alexander Hamilton — then-Secretary of the Treasury — recommended that the Washington administration levy an excise tax on distilled spirits. It was the first time the brand new American federal government taxed a domestic commodity, so it was definitely a test of federal taxation powers — something the previous American federal government, the Articles of Confederation, lacked. The majority of distilled spirits produced and consumed in the U.S. at the time was whiskey, and so the taxation took on the name of the “Whiskey Tax.”

What happened with the whiskey tax? How did this impact relations between federal and state governments?

Whiskey was vitally important to the more rural parts of the country at the time; indeed it sometimes served as currency on “the frontier,” which at that time was Appalachia. The tax had a disparate effect on Western farmers and distillers than it did on coastal producers, and a group of farmers and distillers in Western Pennsylvania (the Appalachian frontier at the time) refused to pay the tax.

Close-up of a 1880 illustration depicting the Whiskey Rebellion | Source: New York Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

Tax collectors were tarred and feathered, held captive in their homes until they agreed to not enforce the tax, or just outright ignored. The situation was approaching the level of an insurrection, so in 1794, George Washington sent in a federal militia of about 13,000 men to quell the rebellion. This showing of federal power — the first of its kind for the new American government — frightened the rebels enough that they disbanded. Throughout the rest of the country, Washington’s response was seen as a huge success for the federal government’s ability to enforce federal law, despite violent resistance.

So in this instance, alcohol also took on a special significance in the ongoing push-and-pull between individual states’ rights and a centralized federal government?

Absolutely. The Whiskey Tax was eventually repealed by the Jefferson administration, which vehemently opposed Hamilton’s Federalist ideology. So, in a sense, alcohol is tied not only to the debate between a larger federal government and larger state & local governments, but also the evolution of the two national political parties. At this early period in the United States’ history, alcohol taxation became another issue around which Federalists and Anti-Federalists were able to distinguish themselves.

Fascinating.

Moving forward, in the 1800’s there was an increasingly popular movement in favor of alcohol temperance (i.e., moderation) and/or teetotalism (i.e., complete abstinence). Many major American religions of the time period began preaching that consumption of alcohol was either a sin in and of itself or at the very least the source of most immorality. As the 19th-century progressed, states on their own began to outlaw alcohol altogether, and, as a result, the temperance movement gained enough political power to push for a ban on alcohol at the federal level. This push culminated with ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919, which imposed a national prohibition on the sale of alcohol.

Prohibition in the United States: National Ban of Alcohol | Source: © WatchMojo.com/YouTube

The Prohibition era gave us speakeasies, Al Capone, and The Great Gatsby, but was otherwise a legal and economic failure — laws against selling alcohol were openly flouted, organized crime flourished, and state treasuries that had depended on alcohol taxes as part of their revenue streams struggled. In 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment, ending Prohibition, as well as returning most regulatory powers concerning alcohol to the states. As I said earlier, in the aftermath of the 21st Amendment, Congress passed the Federal Alcohol Administration Act, which delineated the federal government’s powers to regulate alcohol traveling in interstate commerce. The FAAA is still around today, and is the statutory basis for most of the regulations enacted by TTB.

On a related note — I know that a unified drinking age is a relatively recent legal statute.

When our parents were growing up, the age to purchase alcohol varied from state to state. Why is that? And what changed?

Brendan Quinn

In the wake of the 21st Amendment, many states actually set their drinking age at 21. In the 1960’s, there was an increasing focus on the rights of young people, because many people believed that if you were going to be drafted and sent to Vietnam at 18 years old, you should also receive some other benefits of adulthood like being able to vote and being able to drink. The momentum behind lowering the voting age to 18 culminated in 1971 with the ratification of the 26th Amendment, and after that, using the same logic, lots of states began lowering their drinking age as well.

However, over the 1970’s and into the 1980’s, many studies were published finding a correlation between lowered drinking ages in states and an increase in automobile injuries and fatalities due to driving under the influence. Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) lobbied at the federal level for the passage of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, which was passed in 1984. This law made 10% of all federal highway funds that went to a state conditional on the state setting their drinking age at 21. The constitutionality of this statute actually went to the U.S. Supreme Court in South Dakota v. Dole (1987), which found that this conditioning was an appropriate exercise of Congress’ spending powers. States that wanted the highway money raised their drinking age and every state ended up doing so.

President Reagan Signs the Proclamation National Minimum Drinking Age Bill to 21 on July 17, 1984 | Source: © Reagan Library/YouTube

When I was growing up, adults told me when you’re under 21 it is legal to drink in the company of your parents. Is that actually legal?

Brendan Quinn

The National Minimum Drinking Age Act did not prohibit the consumption of alcohol by minors, just the purchase, so I think it depends on what any given state’s law is on that issue. But it is an interesting legal point: the law is more concerned with possession and purchase for minors, rather than the state of being intoxicated itself.

That’s so interesting to me because, to my mind, that makes alcohol more similar to drugs than other food items.

You’re right to point that out — it’s usually not illegal to be drunk if you’re just sort of sitting there, but you can be arrested for public intoxication/disorderly conduct if you’re behaving inappropriately while under the influence of something. Without that, it’s more the purchase or possession of the substance that is criminalized as contraband, at least for minors. The circumstances where the state of being intoxicated itself is criminalized are instances where what you are doing requires sobriety — driving, operating machinery, performing surgery, etc.

I’ve noticed that, as marijuana becomes legal in more states, the laws around its consumption seem to resemble alcohol laws.

Is alcohol serving as a model for other substances, despite the many differences between marijuana and alcohol?

Brendan Quinn

Funnily enough, I think a lot of the ways people in the marijuana industry have gone about raising public awareness and making marijuana more socially acceptable track many of the ways cigarette manufacturers and alcohol manufacturers sought those same goals. Marijuana is charting a similar course, and, if it becomes legal nationwide, it will be interesting to see how these similarities do or do not persist.

Shifting gears a little — what can you tell us about alcohol advertising? Specifically, how does the government regulate product promotion? Does this fall under the First Amendment?

Brendan Quinn

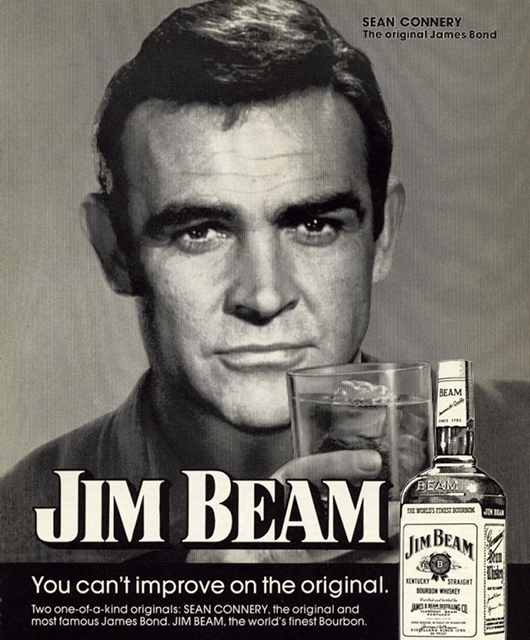

One of the iconic Jim Beam ads starring Sean Connery, from 1974 | Source: Liquor.com

The right to free speech under the 1st Amendment is a fundamental constitutional principle. “Commercial speech” — roughly, speech motivated by economic gain — is constitutionally protected under the 1st Amendment, but receives less protection than, say, private political or artistic speech. False or misleading commercial speech can be banned outright, but if the speech is truthful and non-misleading, the speech can only be regulated if the government demonstrates that it possesses a substantial interest in regulating the speech, that the challenged regulation directly advances that interest, and that the regulation is no more extensive than necessary. This comes from a 1980 U.S.Supreme Court case called Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission.

How does the government go about determining whether something is truthful and non-misleading then?

Brendan Quinn

Claim substantiation is actually an area of the law I am most interested in. You have to balance the 1st Amendment interests of the producer in communicating their message alongside the government’s interest in consumer health and safety (for food and other consumer goods at least).

The government must prove that its interest in regulating the speech is substantial enough and that its intervention is narrowly tailored to directly advancing that interest. For example, it is because of this constitutional balancing that you get those small sheets in medicine or beauty products that contain a ton of information and disclaimers. By permitting the speech with disclaimers and fine print, the government is not restricting or banning the producer’s speech (something that is constitutionally suspect), but instead is making the producer provide the public with the information necessary for the public to make decisions about whether something is healthy or safe to purchase.

This seems like a very optimistic view of consumers! That is, how many people actually read the fine print? Is this a reasonable expectation, that consumers would read all that?

Brendan Quinn

Oh, it’s extremely optimistic. This view of consumers is predicated on the assumption that all consumers are rational actors who read the entire label, the whole box, and all the inserts that come with their products. Further, it assumes that they read all this, think about it, and then make a rational decision to either buy that product or place it back on the shelf while standing there in the store. Now, I don’t know about you, but I feel like most people buy based on flashy advertising or brand loyalty, particularly when it comes to food and other consumer goods. The average person certainly does not spend more than ten, maybe fifteen seconds in front something in the grocery store.

In any case, a lot of commercial speech case law follows the view that the law will not infantilize consumers and courts will not presume that the government knows best. The law does not lightly intervene to tell consumers what they should or should not be consuming or purchasing. The result of this perspective, however, places the burden on consumers to inform themselves.

Returning back to alcohol, how do alcohol advertising and labels get regulated? Is the government inherently at odds with the individual selling alcohol, who wants someone to buy it and consume it, when the alcohol obviously has health risks?

Brendan Quinn

I wouldn’t say the government is inherently at odds with the seller. The government is seeking to protect its citizens’ health and safety, so it regulates alcohol advertising and labeling to ensure it is truthful and not misleading. As I noted earlier, it’s all about ensuring that consumers know what they are getting into and aren’t being lied to.

I’m curious to what degree you think the laws that we have around alcohol are designed to make people feel safe? Do you think that these laws are designed to make alcohol seem safer or seem more dangerous?

I think the government is just trying to have alcohol marketed and advertised in a truthful and even-handed manner, rather than taking the absolute position that alcohol is “safe” or “dangerous.”

It is ultimately for the consumer to understand the risks and/or benefits of alcohol consumption and make the decision whether to consume for themselves. The whole regulatory regime is set up to ensure that producers aren’t only talking about the positives of their products without mentioning the negatives. The consumer needs to understand both sides. That’s why, for instance, most alcohol advertisements warn to “Drink Responsibly.”

Before we wrap things up, I wanted to ask you a quick question that may bring us back to our freshman year of college: what happened with Four Loko?

Brendan Quinn

Ah, yes. In 2009, a group of state Attorney Generals started investigating Four Loko and other caffeinated malt beverage companies because they believed that these drinks were being marketed inappropriately to minors — bright engaging colors, fruity flavors, targeted advertisements, etc. — and that the caffeine increased the likelihood of blacking out and masked the effects of intoxication.

“Blackout in a Can”: CBS | Source: © CBS/YouTube

In response to this — and the fact that lots of college campuses were getting out of control from students drinking them — colleges started banning Four Loko and other alcoholic energy drinks on their campuses. By the time we started college in the fall of 2010, the Four Loko wars were in full swing and peaked with a warning letter from the FDA in November 2010. The letter stated that the caffeine and other substances added to these drinks were “unsafe food additives” and that Four Loko and other similar companies could face civil and criminal penalties if they continued to sell the products as they were then-formulated.

In response, Four Loko pulled the “original recipe” off the shelves and reintroduced the product in December 2010 without the caffeine, taurine, and guarana — effectively neutering the “energizing” effects of why college students drank it in the first place. And that’s why we “grew up” in college hearing stories from upperclassmen about the halcyon good ol’ days of “real” Four Loko.

Thank you so much for your time!

Editor’s Note: The author of this article is not a licensed attorney. The information contained in this article is not legal advice and it is not a substitute for legal advice.

Brendan Quinn

is a recent graduate of Georgetown University Law Center and proud double Hoya, having also graduated from Georgetown undergrad with a degree in Theater & Performance Studies and Psychology. He is a law clerk at a law firm in Washington, D.C. His legal interests include intellectual property and food & beverage regulation, stemming from his background in the arts and employment at a vineyard prior to law school. When not absorbed in the law, he spends his time cooking, wine tasting, and striving to be as effortlessly sophisticated as Ina Garten.