NATALIE GALLAGHER

In this issue we chat with Hollen Reischer, a second-year graduate student in Northwestern University’s psychology department, working with narrative researcher Dan McAdams. Recently, she’s been focusing her research on people’s experiences of self-transcendence and how they relate to their life stories. We sat down with her to talk about storytelling and psychology. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Hi Hollen, thanks for making the time to do this interview!

Can you tell us a little bit about narrative psychology: Where does it come from? What’s its perspective?

Hollen Reischer

The interest in narratives is about how we as individuals live storied lives — we see ourselves as part of an unfolding story, and the story is our experience as a person, but also as part of an unfolding story in our community, the world. The underlying theory that we look at in my lab is the theory of narrative identity, which posits that there are three layers of personality development. When you’re born, you start out as an actor in your own life. In later childhood, you become an agent in your life. The part that we’re really interested in is emerging adulthood, when this authorship part of one’s personality develops [and] when one starts to think of their life as a potentially cohesive story in which one’s experiences make sense together.

We kind of think of it as a ‘life project’ that people have: to understand their story in a way that makes sense for their life and integrates their experiences, ideally in a healthy way. This theory of narrative identity is our underlying assumption; that people are authors of their own life stories and are engaged in this project of authorship for the rest of their lives. We think that understanding how people conceive of their lives and tell their life stories — both to themselves and to other people — can really tell us a lot about how people function in the world in different ways.

The idea is that this is something you’re doing all the time, internally?

A common thing people will say is, “I’m not thinking about my life story every day. How often am I telling someone my life story?” Which, admittedly, is a rare opportunity. We’re aware of that, and we don’t think that every morning people wake up and say, “How is what I’m going to do today going to fit into my life story?” But there are moments when they’re engaged in conversation and someone asks about some important aspect of their life — and all of a sudden when [they’re] telling it there’s a context that comes before it, and it led you somewhere. So it’s how we are who we are today, how we make sense of that to ourselves.

Source: The British Library/Flickr

Also, when one experiences a particularly important moment in life — as a high point or a low point or a turning point, for example — these are moments that can be kind of seared into your memory. Part of why they’re important is because it was a transition, or because it helped put things in a new perspective, or made one realize what their values were. So it’s this internal process that’s going on and only comes into conscious focus occasionally.

What brought you to doing research like this?

Hollen Reischer

There was this wonderful place at Duke University called The Center for Documentary Studies, which is all about documentary storytelling through different mediums; I was focused on photography. We focused a lot on what it means to work with people, to understand their stories, in an ethical way — the power of storytelling and how precious of a gift it is to be able to share personal experiences from someone’s life. I was kind of developing this curiosity in the inner workings of people as a psychology major, and a real interest in how people are read by others, and being the facilitator between those processes. A lot of my professional experience after college was helping people tell their stories, mostly for social justice reasons.

The most pivotal [role I had] was at an organization called the [now-defunct] Neighborhood Writing Alliance (NWA) which ran writing workshops for adults living in low-income neighborhoods throughout Chicago and at public libraries and social service agencies. [We created opportunities] for adults to get together in a safe space and just tell their life stories — write their life stories, but they would talk about it in the community also. I really saw there how important it is for people to be able to tell their stories; for people to read those.

Are these stories all on a website somewhere; are they published, or was the point this communal sharing of them?

Hollen Reischer

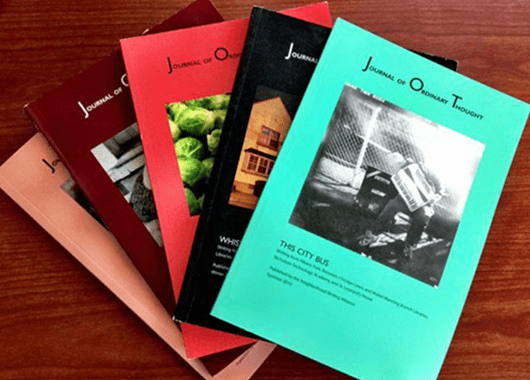

Journal of Ordinary Thought | Source: © Chicago Reader

It was published in something called the Journal of Ordinary Thought, the motto of which is “Everyone Is A Philosopher.” I think the publication is the most powerful piece of [the work] because it’s in the Chicago Public Library — it’s archived in some places [and] any person can access these stories that are mostly unheard, of ordinary people in Chicago. While I was there, I really saw the many different ways people can see their life stories that are really independent of what the specific experiences in the stories are. So a given event could be seen in retrospect as something that was life-changing in a positive way; that the individual grew and that it informed who they are today. Or it could be something that was really hard to move past, and always a tragedy to keep returning to.

When you were talking with folks there, were the conversations about the content events or about the sort of evaluative frame and the way that the person was telling the story?

That’s an interesting question because that kind of echoes what we [at Northwestern] do in our work [and] in my research. A really interesting part of the storytelling is what the narrator chooses to tell, which could be anything from their life experiences. So I mean people would write about mundane — seemingly mundane — experiences, like the watermelon man who used to come down their street as a child, and what maybe culture might consider large events, like combat experience or an abusive relationship.

Do you want to talk about the Life Story Interview and how you usually do that?

Hollen Reischer

The most treasure-filled data that we collect in our lab is called the Life Story Interview. We use a particular interview that consists of about 18 questions. It asks really big questions.

In some interviews we might ask, “Imagine your life story like a book; tell me what the chapters of the book would be, what the titles of those chapters would be, and a brief summary about what happens in each chapter.” We ask what the high point of your life is, the low point, a turning point. We ask about challenges: “What’s the biggest health challenge you face; What’s the biggest career challenge; What’s your biggest failure or regret?”

We give them a little more prompt, but in general, people are really eager to tell their stories and have a lot of stories to tell.

Do you have a favorite question?

Hollen Reischer

The regret and failure question. I’ve spent a lot of time with that question, because there’s really a range in how people talk about regret and failure. Pretty much everyone has had an experience in their life — or done something in their life — that they might consider a failure. But then there’s a lot of ways to go from there. Some people have this regret that, when they talk about it, you can feel the devastation. It was so awful, there’s really no moving forward from it; they’re kind of stuck in that moment right now. On the other end of the spectrum there’s people who [say,] “This thing happened, it was awful, I failed at this, but then I learned so much from it.” Or some people [say,] “I don’t even believe in regret, that doesn’t do anything for me.” So there’s such a range.

From a story point of view, the turning points are [also] really interesting to hear. High points are great and they make you feel good, but there’s a lot of common high points — your wedding [or] the birth of your first child; those come up a lot. And low points are obviously uniformly sad to read, usually. Turning points could just be anything; it could be a positive event, it could be a negative event, it could be almost something that’s a non-event but then the way the person chose to interpret that event turned their life around. Those are some of the really most powerful moments, I think, in people’s life stories.

Lastly, I’d love to hear you talk about the obituary project you’ve been working on!

Hollen Reischer

Source: The British Library/Flickr

I’m very interested in obituaries, from ethical and storytelling points of view. Obituaries are interesting because they kind of purport to tell one’s life story but in most cases the one whose life story is being told is not the one telling it. So there’s this underlying assumption that there’s an effort to tell the story in a truthful way, but also perhaps a flattering way. I’ve been particularly interested in obituaries related to people who have died unexpectedly and perhaps in a socially unacceptable way — so that would be, in our society, suicide [and/or] drug overdose, and others. What are the obligations to various stakeholders in telling that life story? I see the stakeholders as being the deceased, the bereaved, and the public. It’s arguable what they deserve or don’t deserve or what is ethically appropriate. And there’s a real tension about disclosing cause of death. Is there this truth-telling that’s most important? In some cases it’s public health that’s most important. Is it this strong desire we have to not speak ill of the dead that’s most important?

Some of the research I’ve begun to do on this looks at how the obituary itself is a narrative that can serve many purposes. Looking at obituaries specifically about people who have died from a heroin overdose, for example, […] sometimes these are used as calls to action for other people in the community, maybe to such an extent that the person’s life story is almost absent, and their life is kind of reduced [to a few words]. Other times it’s just a declaration [that] “this happened, and now this person has this whole rest of their life that we want to talk about.” So there are various stories that are told that function in really important ways that reflect social issues.

Did you know Carrie Fisher wrote her own obituary?

No! What if that was a thing we did every year, on our birthday? What if we were like, “It’s my annual review, and I’m going to write my life story as I want others to hear it.”

It’s kind of morbid sounding, but cool in a way. This would be a much more creative exercise than [having a will]. That would be a good thing for everyone, perhaps. It could be stressful. I think it could be cool. I think I should start the living obituary project.

Do you have anything else you want to add before we sign off?

Hollen Reischer

I was reflecting on how the work I used to do relates to the work I currently do. Obviously storytelling is the common thing. But I think it’s not just storytelling; the real focus at NWA was the value of the stories and the validity of them. In psychology we are studying human beings and how they think about [and] experience the world — at least this is what I’m interested in — and make sense of the world. And I think stories are so valuable.

I think that it’s really important for us as researchers to take seriously what our participants have to say about their experiences and their lives and, whether you’re in narrative research or not, care about that and understand that it’s really valuable data for us to collect and try to understand — how to integrate people’s own understanding of themselves into our research.

Thanks for your time Hollen!

Hollen Reischer:

She is a doctoral student in Clinical Psychology at Northwestern University. She is a member of the Foley Center for the Study of Lives and a founding member of her department’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee. She is particularly interested in issues of human connectedness, including self-transcendence and the experience of beauty, and how these experiences show up in our self-narratives. Previously, Hollen has worked in PTSD research, in gaming for social good with Seeds, with gifted writers in underserved neighborhoods at the Neighborhood Writing Alliance, for low-wage workers at Interfaith Worker Justice, and with other young people on a range of social justice issues at Avodah. She is also an editor for the mischievous architecture periodical SOILED and helps people communicate their personal stories with Voice & Ink. Inspired by this interview with 6x8P, she just bought livingobitproject.com.