EMMA JACOBS

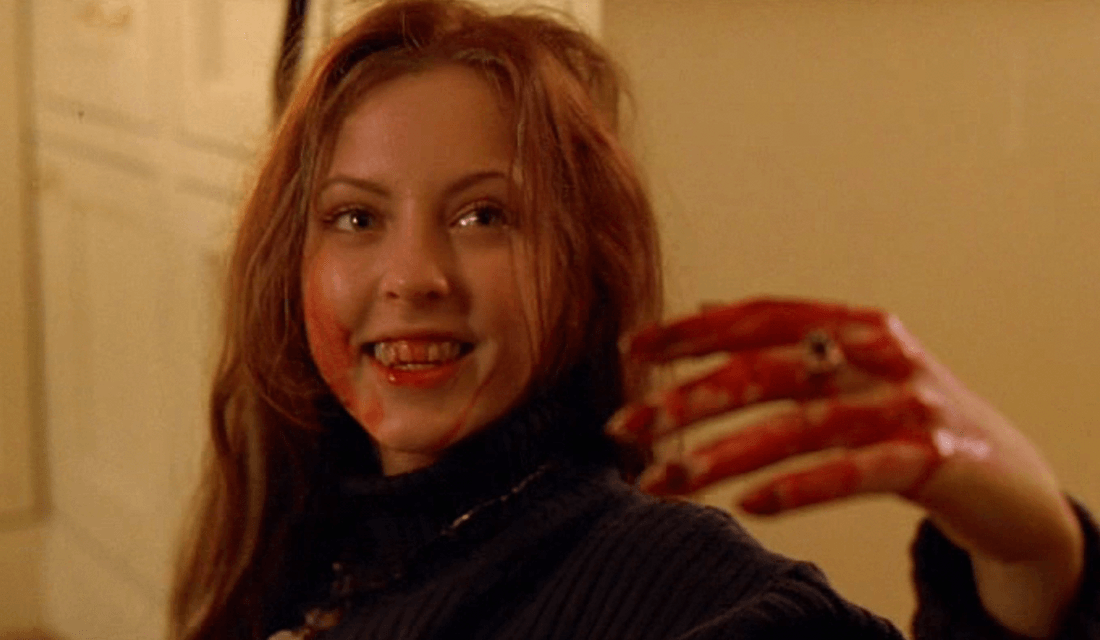

The most famous scene in the most influential horror movie in cinema history begins like this: A beautiful woman undresses, and steps into the shower. We see her feet as she kicks off her slippers, then her bare calves, then her knees. The outline of her nude form is just barely discernible through the polyurethane shower curtain she has now drawn across our field of vision. But soon, we are in the shower with her, watching her lather naked shoulders as the water cascades over her head. Her mouth is slightly open in pleasure; she is unaware we have intruded upon her private ritual. She is unaware, too, of the bathroom door which has opened behind her and of a shadowy figure standing in the doorway. We know, because we have a view through the shower curtain. But we say nothing. We are waiting for something to happen. The figure comes closer and rips the shower curtain open. Suddenly, a score of screaming violins fills the soundtrack, matching the hysteric soprano of the woman’s horrified scream, as she turns around and sees a figure holding a knife. She realizes that she will die, and so do we. Again, we say nothing. The killer slashes at the woman’s body again and again, the knife eliciting sickening, fleshy noises as it makes contact. Blood flows into the shower’s stream, creating a current on the bathtub floor. The woman turns around as if to protect herself, but the killer stabs her in her back, before leaving through the open door. The woman’s nude body which seduced and enthralled us has now been penetrated and discarded. We did nothing.

The Shower – Psycho (5/12) Movie CLIP (1960) HD | Source: © Movieclips/YouTube

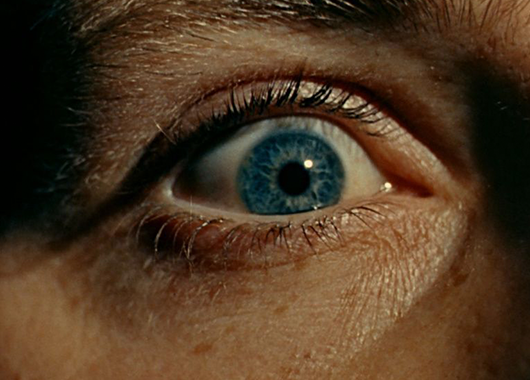

Or how about this: the opening scene of another horror film, released the same year, begins with a closed eye springing open to reveal an iris of intense and terrifying blue. We then see the figure of a man on a dark street, approaching a woman in a red skirt and a brown stole standing at the shop window of a clothing store. The man has something concealed in his coat: a camera, whose three unblinking lenses stare out at the woman. She does not see them, even as the camera whirs to life and our perspective shifts to that of the concealed device. We watch her being watched, soliciting for sex. We — as the man’s secret camera — follow her up the stairs into a dingy apartment, watch as she gets slowly undressed on the bed. The man’s hand comes up to the camera lens and something changes; a reflective light now is cast over the woman. She sees this change and her expression changes from one of boredom to one of utter fright. She backs away on the bed, but it’s too late. The camera gets closer as she screams. She realizes that she will die and so do we. We do nothing.

What kind of sick fuck would watch this filth for entertainment? The title of the film soon flashes across the screen, as if providing an answer to this very question: Peeping Tom.

Peeping Tom (1960) – Trailer | Source: pirika666/YouTube

Both Psycho and Peeping Tom were released in 1960, sparking a cinematic fascination with the sexualized murder of women at the hands of deranged men. Many film historians consider Psycho the first entry in the now-classic horror subgenre of the slasher, the formula of which is dedicated to this very theme. Savvy filmgoers can quickly recount every slasher trope: a group of people — usually but not exclusively teenagers — is being hunted and watched by a (oftentimes masked or otherwise obscure) male figure. Members of this group are picked off and killed (sometimes moralistically or sexually, almost always gruesomely) one by one, until only one person remains: a young and willful woman who must fight for her life against the killer. Elements of misogyny in both the prior deaths and the final confrontation between the last woman standing and the masked madman are crucial to the slasher category (and the horror genre at large). Not only are most of the killer’s victims female, but they are almost always killed in the nude, in otherwise compromising positions, or by a laughably phallic weapon that repeatedly penetrates their bodies. Worse, many female characters of these films are violently killed precisely because of their sexuality. Marion Crane in Psycho is murdered by Norman Bates because she has piqued his sexual interest. Dora, the sex worker in the opening scene of Peeping Tom, makes the mistake of soliciting Mark Lewis for sex and is fatally punished for her choice. Our bloodlust is vicariously sated with old-fashioned human sacrifice.

We know, because we have a view through the shower curtain. But we say nothing. We are waiting for something to happen.

We as viewers are sometimes invited to identify with the perspective of the killers (either through the use of POV shots or dramatic irony); we revel in both our own passive action and the sex and gore on display. But we can’t get the full picture if our vision is limited to that of the man behind the mask. Isolated scenes from certain films and broad discussions of ostensibly misogynistic tropes fail to capture the full scope of horror cinema. Identification in horror is unmoored, unfixed from its traditionally gendered lines. Our gaze and sympathies lie with the victims more often than with the man behind these deaths. Take again Psycho’s central shower scene, which embodies this form of oscillating viewership through its use of disorienting cross-cutting shots. Sometimes we are Marion, exposed and watching the knife come towards us. Sometimes we are Norman, obscured and watching as we end Marion’s life. Crucially, though, the scene does not end when Norman hurriedly walks out of the bathroom, his murder almost completed. We do not follow him through that door. Instead, the camera and its spectators stay on Marion, whom we watch in her tragic death throes. We watch her hand claw first at the wall of the shower, then at the shower curtain, looking for anything to hold onto in her last moments. We watch her keel over and die, the camera lingering not on her nude body, but on her eye, which has had the life drained out of it. Her eye is a mirror to ours in the moment, wide-open in a posture of shock and unadulterated terror.

Psycho‘s final shot of the infamous shower scene | Source: Quora

Just as horror cinema blurs lines of viewer identification, so, too, does it muddy the gender identities of its characters. Norman Bates is, after all, dressed in drag as his own mother even as he plunges a knife into Marion’s breast. As professor Carol J. Clover argues in her seminal study of gender in horror cinema, the killer is often coded as effeminate in both affect and psychological development, whereas the “final girl” who survives the film is tomboyish, masculine, and resourceful. Clover notes that horror films necessarily invoke a “loosening of the categories” of both the gendered subjects and of the viewers, “at least of the category of the feminine.” If we as viewers are consistently asked to understand and identify with the male antagonist, we are just as often asked to identify with the female protagonist, regardless of who we are as subjects. The feeling of horror, the raison d’être of the entire genre, arises from this deeply rooted uncertainty. If we viewers were only intended to identify with the male killer, what would that make of our relationship to terror? How could we as viewers be effectively frightened if we were always the man behind the mask, the harbinger of death, the person in control of the lives of others? If we always knew what would happen — if we unwaveringly wished for the on-screen deaths of our characters — what would we really have to fear?

A scene from Peeping Tom | Source: Pinterest

The charge of misogyny in horror cinema simplifies not only the complexity of gender and vicarious identification at the heart of the genre, but also the ways in which these films telegraph their self-awareness and play with their own conventions. Peeping Tom is more than a movie about a man who films the deaths of the women he murders. It is a movie about the very voyeurism and scopophilia in which it ostensibly indulges. The camera itself is the murder weapon, and we the uneasily willing accomplices. In underlining Mark’s troubled past and his Freudian relationship with his father while simultaneously painting the female lead Helen Stephens as stable and intelligent, Peeping Tom indicts the viewer who seeks only to identify with the killer. If you root for him, you’re missing the message. These are films that seek to build an unsettlingly attractive paradigm of empathy, yet which stop short of commendation.

Far from unwittingly embracing the tropes which many critics have accused as retrograde and offensive, horror films have — from the very beginning of the genre — turned them on their head. Classic slashers like the first Friday the 13th (1980) subvert expectations by revealing the masked killer to be a grieving mother, while horror flicks like Carrie (1976), Ginger Snaps (2000), and Teeth (2007) ensure that our empathy lies with the female protagonists even as they themselves develop monstrous and horrific powers. Even entries from subgenres that appear more overtly and unquestionably exploitative are clearly interested in the complexities of gender, fear, and violence. How else to explain the fact that Daughters of Darkness (1971), an archetypal example of the erotic-lesbian-vampire-horror film, has the female villain proclaim to the female protagonist, “Stefan loves you. Of course he does. That’s why he dreams of making out of you what every man dreams of making out of every woman: a slave, a thing, an object for pleasure.” The scene comes, of course, after we witness the male hero beating the female protagonist, his wife. Questioning gender and power is part of the DNA of each and every horror film. Fear arises from these questions, and from the confusion they purposefully elicit.

If we as viewers are consistently asked to understand and identify with the male antagonist, we are just as often asked to identify with the female protagonist, regardless of who we are as subjects.

Perhaps, then, the truth is that horror films are neither inherently misogynistic nor implicitly feminist. Clover herself is quick to point out that calling the “final girl” a feminist creation would be “a particularly grotesque expression of wishful thinking.” And yet to reduce the entire genre to an expression of one-sided power — to ignore the many ways the women of horror are not only the victims but also the heroines, the monsters, the emotional centers of these films — is to consign a multivalent art form to a life of unambiguous predictability. If there’s one thing worse than an un-scary horror film, it’s a boring one. Accomplished horror movies pull off a bait-and-switch, drawing you in with the promise of breasts and blood. Before you know it, though, something else has snuck up on you — a creeping fear that, just maybe, you too are being watched.