ROBERT DUFFLEY

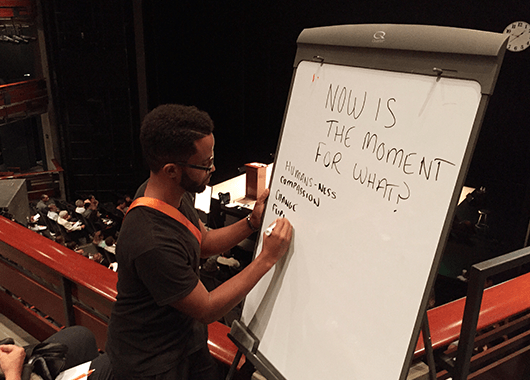

Barring a surprise bigger than that of his election, Donald Trump will be inaugurated as the 45th president of the United States in January 2017. It would be foolish to claim that art alone creates political or social change, or that art easily or inevitably combats these forces. Trump’s unpredicted election has revealed the disastrous extent to which self-stratification has created echo chambers within America’s actual and cultural geography. Even more than social media, art — with its well-documented concentration in liberal urban areas, high ticket prices, and elitist standards of access — can simplify and amplify opinions for the exclusive benefit of an already-unanimous audience.

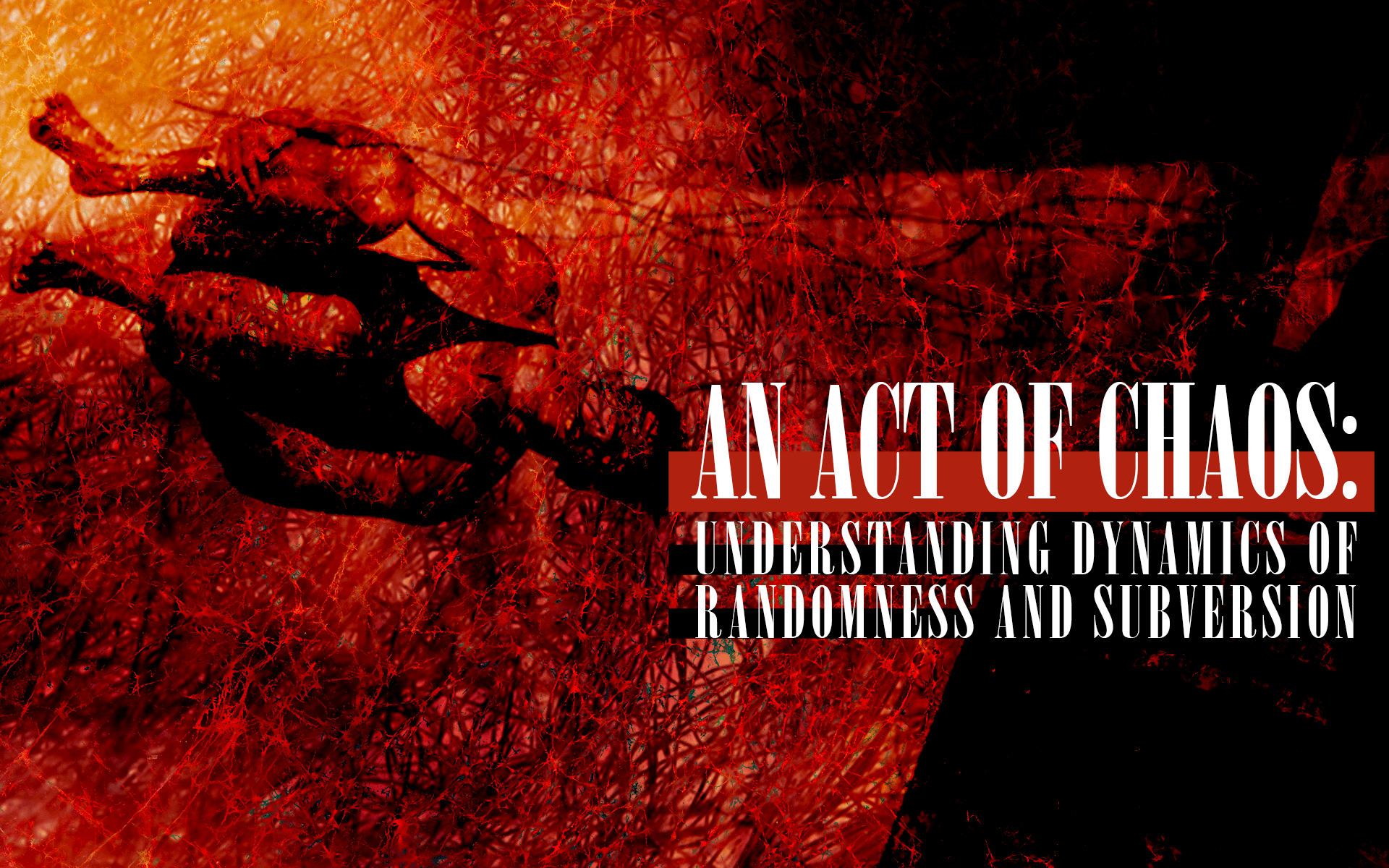

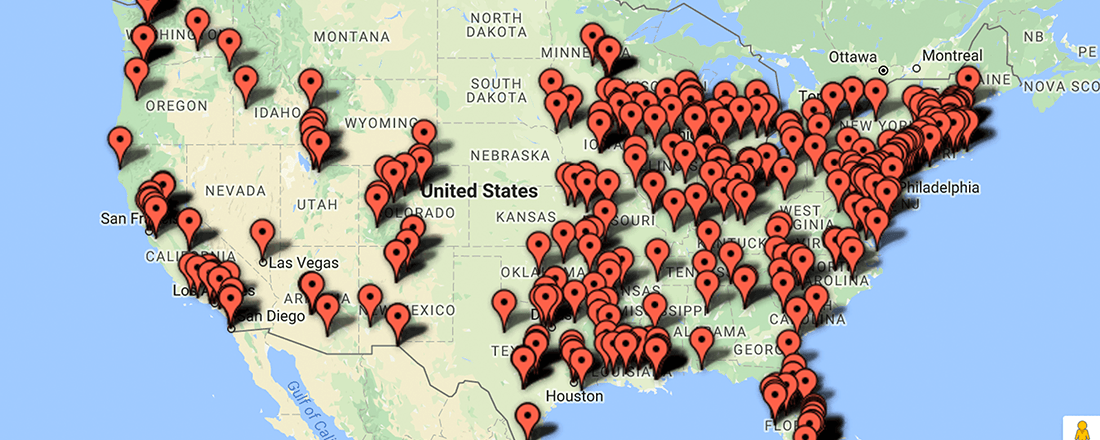

The uneven distribution of cultural districts across America | Source: Americans for the Arts

And yet, as the chaos threatened by any number of Trump’s trademark proposals looms, artists around the world would do well to reflect on the rare but potent instances when the arts have succeeded in crossing barriers of access and understanding in order to inform, register, or incite protest. Theater, at its core, requires presence — of both artists and audiences. When theater is able to step out of the echo chambers, into the intersections of culture and politics, this presence grants theater an unparalleled vitality. Simply put, effective protest theater places dissenters not only in earshot, but in reach of the individuals and ideas they fight. While many individuals detailed below have paid high prices for this proximity, it has also enabled a genuine contact not guaranteed in the use of other forms.

How does theater register protest, or organize communities towards action? Through three case studies, this essay charts three key strategies for protest theater: aesthetics as critique, radical encounters, and audience mobilization. These categories are not set in stone; several pieces discussed below could be argued to include a hybrid approach. However, each method embodies a distinct conception of the relationship between performance and power. My intent in this survey is to provide an organized inventory — for inspiration, education, and mobilization — of core tools available to theater-makers looking to register protest. It is my belief that we will need them soon.

Aesthetics as Critique: OBERIU

Today I Wrote Nothing, a collection of Kharms’ stories and writings, including “The Redheaded Man” | Source: Amazon

“There lived a redheaded man who had no eyes or ears,” begins “The Redheaded Man,” a 1937 short story by the Russian author Daniil Kharms. “He didn’t have hair either, so he was called a redhead arbitrarily. He couldn’t talk because he had no mouth. He had no nose either. He didn’t even have arms or legs. He had no stomach, he had no back, he had no spine, and he had no innards at all. He didn’t have anything. So we don’t even know who we’re talking about. It’s better that we don’t talk about him any more.” This grotesque fragment registers a chilling critique of forced disappearances in Stalin’s Russia. Beginning with a familiar fairytale invocation, the piece veers into nightmare, demonstrating how quickly the clipped, utilitarian language of official inventory can efficiently dismantle both bodies and identities — leaving only haunted gossip in their wake.

The now infamous image of Stalin and former head of the Soviet secret police Nikolai Yezhov, who was doctored out of photos following his execution | Source: Business Insider

The potent absurdity of this story represents a crucial strategy for protest art: aesthetics — language, form, narrative — utilized to mimic and deconstruct official narratives and languages of power. OBERIU, the loose literary collective which Kharms formed with Aleksandr Vvedensky in the U.S.S.R. in 1928, exemplifies this approach. Working against the background of the manifestoes, declarations, and the five- and ten-year plans which masked Stalin’s brutality in terms of progress and glory, OBERIU’s early performances dismantled the bluster and pomp of revolutionary language. Articulating the potential of this work, Kharms wrote, “We must write poems which, if thrown out the window, will shatter the glass.”

1935 children’s poem written by Aleksandr Vvedensky titled Zima Krugom (Winter All Around); the poem translates into the following: We Pioneers / Are not afraid of winter / We Pioneers / Have no need of coats / We Pioneers / Need skis / We Pioneers / Love the cold! | Source: © The University of Chicago Library

The group began by performing flamboyantly chaotic variety shows, stories, and plays. Mixing visual art, theater, magic, and sound-poetry called “zaum,” these shows endeavored to dynamite the boundaries of sense. In one variety show, Kharms performed magic in front of a hand-painted banner reading, “Art is a cupboard! We are not cakes!” The potency of OBERIU’s work stands in direct relationship to the continuous pressures of censorship on its authors. Working as children’s book authors, Vvedensky and Kharms published and performed very little of their adult work during their lifetimes. Their cabarets were halted in 1930, when a partisan journal denounced their work as “literary hooliganism.” In 1931, the artists were arrested, convicted, and sentenced to exile for counter-revolutionary activity — in both their performances and their writing for children. Following their release in 1932, both artists stopped performing publicly but continued to write.

2013 production photo of Gogol Center’s Christmas at the Ivanovs’ | Source: © The Moscow Times

Vvedesnky’s dramatic masterwork, his 1938 ghoulish comedy Christmas at the Ivanovs’, blurs absurd violence and brutal illogic. Written in 1938, the play takes place on Christmas Eve in turn-of-the-century St. Petersburg, at the manor of the respectable Puzyrov family (despite the name, there are no Ivanovs in the play, since — roughly the equivalent of “Johnson” — Ivanov is a common Russian surname; furthermore, Puzyrov is a nonsense word that can loosely be translated as “Of Bubbles”). There, the holidays take a turn for the worse when, at bath time, the nanny beheads 9-year-old Sonya with an axe. Busy at the ballet during their daughter’s murder, Mr. and Mrs. Puzyrov return home to a difficult choice: how to pay the requisite respects to their newly-offed Sonya without putting a damper on the household’s Christmas fun. The piece’s humor lies in its characters’ desperate attempts to remain oblivious to mounting horror. The Puzyrovs’ (phony) grief is foiled repeatedly by the fact that Sonya simply won’t stay dead. She is coffined, escorted out the door, and stuffed into a wardrobe — but nothing keeps the murdered girl away. She wanders through scenes uninvited, pale and solemn as a macabre sleepwalker, a sopping scarlet ribbon tied around her neck.

Neither author ultimately escaped the threat of illogical violence which saturated their work. As the German army marched towards St. Petersburg in 1941, both artists were arrested again. Vvedesnky died on a prison train headed to exile in Kazan; Kharms died in a prison during the siege of St. Petersburg, likely of starvation and exposure. Only published in the 1990s, Vvendensky’s papers were stored in secret for most of Russia’s bloody twentieth century.

Despite limited opportunities for performance in its authors’ lifetimes, OBERIU’s work has a strong legacy. Christmas at the Ivanovs’ was first published by an emigre press in New York in the 1980s; its premiere professional staging came in 1997 at Classic Stage Company in New York. In 2013, the work received its controversial Russian premiere, running at Moscow’s Gogol Center under the direction of Denis Azarov. That production invokes not only a lost play but the ghosts of a generation; against a backdrop of mounting censorship, including death threats to the Gogol Center’s artistic director and recent exhibit closures — the play’s atmosphere of unanchored menace seems chillingly relevant. More aesthetic homage than political critique, Robert Wilson’s The Old Woman — an absurd vaudeville featuring Willem Dafoe and Mikhail Baryshnikov — shared Kharms’ tale with a wider Western audience.

Willem Dafoe and Mikhail Baryshnikov in The Old Woman | Source: © The American Reader

While to claim direct influence is complicated due to the obscurity of OBERIU’s work for most of the 20th-century, their radical aesthetics exhibit similarities to many other, more widely- known theater artists. As spotlighted by Teju Cole immediately following Trump’s election, Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros soars outside the boundaries of logical to portray the mass delusions accompanying a fascist’s rise. Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui — which will receive a high-profile revival in 2017 at London’s Donmar Warehouse — takes similar steps. Caryl Churchill and Maria Irene Fornes’ works in the 1970s and 1980s shattered traditions of dramatic form to leverage lasting feminist critiques; Wole Soyinka’s 1975 Death and the King’s Horseman distorts traditional narratives of encounter to give voice to painful logical distortions embedded in colonial experience — the list of powerful examples of this approach is long, and more extensive comparisons would be productive.

The potent absurdity of [the illogical, rebellious] story represents a crucial strategy for protest art: aesthetics — language, form, narrative — utilized to mimic and deconstruct official narratives and languages of power.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Outside the boundaries of the professional theater, however, one particular descendant of OBERIU demands consideration for its world-famous use of radical aesthetics to leverage critique of political power. Following their “punk prayer” at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 2012, Pussy Riot’s members were tried and convicted of hooliganism. Nadezhda Tolokonnikova — giving a closing argument in her own defense — cited OBERIU directly (specifically, Aleksandr Vvedensky): “At the cost of their lives, the OBERIU poets inadvertently proved that their basic sensation of meaninglessness and alogism was correct: they had felt the nerve of their epoch. Thus art rose to the level of history […] OBERIU are thought to be dead, but they are alive. They are punished, but they do not die.”

Radical Encounter: Bread & Puppet and Yuyachkani

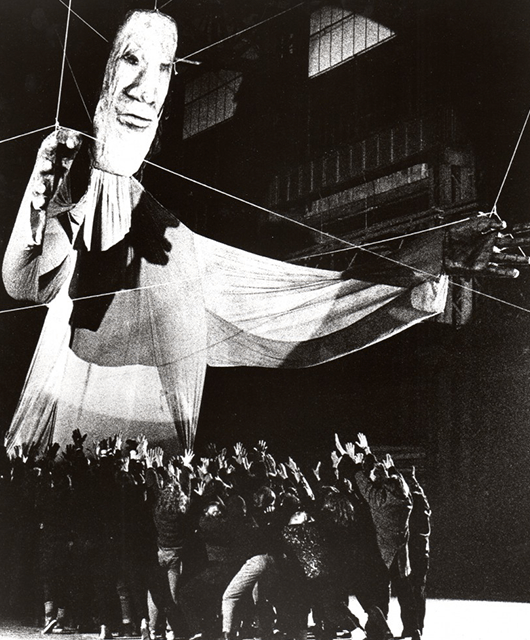

If the executives of BP, Shell, and TransCanada ever reviewed photos of the People’s Climate March — a massive demonstration in New York in September 2014 — they may have been surprised to see themselves among the marchers. Constructed and wielded by Bread and Puppet Theater, the bloated, pork-pink, papier-mâché effigies bobbed above the crowd on Central Park West, with skulls, fleeing deer, and slogans flying in their wake.

People’s Climate March protest in NYC | Source: Bread and Puppet Theater/Facebook

This spectacle represents a second core technique of protest theater: that of a radical encounter. In general, this radical encounter involves the appearance — in a civic space — of an individual or an idea which would otherwise be absent. The radicality of this approach is its physicality: performance gives physical form to the persons, memories, policies, or projects otherwise confined to abstract or verbal reference. At the most basic level, this approach was visible in the 2016 Guy Fawkes Day celebrations in England, where revelers burned effigies of Donald Trump days before the U.S. election. Executed by professional theater companies, the sophistication of these encounters scales upward in relation to the technique, volume, and narrative of the presences invoked by performance.

Source: Bread and Puppet Theater

In their protests and performances since the Vietnam War, Bread and Puppet have facilitated radical encounters between protests and their objects. In “The Radicality of the Puppet Theater” — a manifesto for the group — founder Peter Schumann asserts that political puppetry works by “representing, more or less, the demons of society.” In Vietnam War protests, the troupe carried effigies of Uncle Sam alongside menacing skeletons, as well as Vietnamese women and children in funeral shrouds. Other performances have represented public figures ranging from political prisoners to congressmen.

This focus on embodying figures often at the center of, but physically absent from, civic discourse lends Bread and Puppet a flexible production model. As in the People’s Climate March and the aforementioned Vietnam War protests mentioned, radical encounter is achieved by incorporating basic performance into traditionally non-theatrical spaces. This type of performance emphasizes spectacle over narrative, lending otherwise non-performative protests iconic visual elements with symbolic value. At their base of operations in Glover, Vermont, as well as in theaters and other spaces around the world, Bread and Puppet have also performed full-length plays. With smaller audiences — but greater aesthetic control — these performances have more elaborate narratives, as in the 2015 production of Seditious Conspiracy Theater Presents: A Monument for the Political Prisoner Oscar Lopez Rivera, which advocates for the release of a U.S. political prisoner by telling the story of his arrest within the larger context of U.S. occupation in Puerto Rico.

The radicality of [the Bread and Puppet] approach is its physicality: performance gives physical form to the persons, memories, policies, or projects otherwise confined to abstract or verbal reference.

Though Bread and Puppet’s exclusive reliance on puppetry is unique, the core technique articulated and exemplified in their work — creating, through representation, a radical encounter — has been a crucial protest performance methodology across cultures. Both the strengths and risks of this methodology lie in the issue of proximity at its core: placing performance in non-theatrical, optimally civic public spaces. For Schumann, the public confrontations between social spaces and their “demons” is capable of, and designed to, provoke conflict; the technique, he argues, should give “purpose and aggressivity back to the arts and make the gods’ voices yell as loud as they should yell.” Arrested at multiple sites — including the 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia — Bread and Puppet asserts that their art is “easier researched in police records than in theater chronicles.”

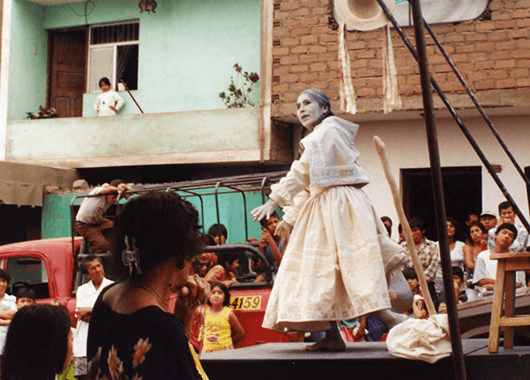

2002 production photo of Yuyachkani’s Rosa Cuchillo | Source: © Katherine Nigh/Hemispheric Institute

Police records are of central importance in the work of Peruvian theater troupe Yuyachkani, which also exemplifies the methodology of radical encounter. Taking its name from a Quechua word meaning “I am remembering,” the troupe’s mission is “to contribute to the development strengthening of civic memory.” Emphasizing questions of ethnicity and violence in 20th-century Peru, their work has used the embodiment inherent in theatrical performance to create radical encounters between civic spaces and their memories which have been either forgotten or suppressed.

For Yuyachkani, this encounter with civic memory often takes place through the appearance of a ghost. In Adiós Ayacucho (first performed in 1990), the ghost is Alfonso Cánepa. Based on a short story by Julio Ortega, the play begins just after Cánepa, an indigenous farmer, has been murdered, mutilated, and disappeared by a military death squad in the conflict between Shining Path and the government and paramilitary forces combating them in Peru’s rural High Andes region. Rising from his impromptu grave, the ghost decides to bring a letter, addressed to the President and demanding justice for his and others’ deaths, to Lima.

1990 production photo of Adíos Ayayucho | Source: © Hemispheric Institute

Theater scholar Francine A’ness ascribes the performance’s strength to its simplicity and resemblance to clowning: “Rather than attempt to compete with the media and approach the topic of violent death and disappearance through the explicit lens of documentary theater, the story is communicated through a simple monologue and a contemporary dance-inspired aesthetic.” As with Bread and Puppet, the simplicity of this technique lends the performance both approachability and flexibility.

[Radical encounter] performance emphasizes spectacle over narrative, lending otherwise non-performative protests iconic visual elements with symbolic value.

In addition to theater spaces, Cánepa has also told his story in public marketplaces and at demonstrations. While original performances of Adiós Ayacucho began in 1990, Yuyachkani resurrected Cánepa in 2002, on the occasion of the formation of Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As crowds waited in Lima outside the Government Palace for the Commission’s official beginning, actor Augusto Casafranca — in the guise of Cánepa — climbed onto the palace steps and recited his long-awaited letter for the President:

“Dear President: I, Alfonso Cánepa, the undersigned, citizen of Peru, domiciled in Quinua, occupation farmer, directs himself to you, the highest political representative of the Republic, to express the following: On the 15th of July I was arrested by the civil guard of my village. Placed incommunicado, I was tortured, burned, mutilated, and killed. I was declared disappeared […] tell you this as one of your victims, one who has nothing to lose, and I speak from personal experience. I want my bones, I want my body, complete and whole, even in death.”

– Augusto Casafranca (as Alfonso Cánepa)

This moment represents the flexibility which uniquely empowers protest theater of radical encounter: originally scripted as part of a theatrical performance, a character is able to participate, with very little alteration, in a decisively non-theatrical public moment. As with Bread and Puppet’s effigies of CEOs, bombing victims, and casualties of Canada’s tar sands oil operations, these performances represent a powerfully symbolic intrusion into civic spaces which existing power structures might prefer to keep in a state of blindness or amnesia.

Audience Mobilization: Notes from the Field and Cornerstone Theater

A third type of protest theater breaks traditional boundaries between performer and spectator, incorporating audience members directly into the performance in order to catalyze civic action.

Anna Deavere Smith’s legendary documentary solo performances — which places individuals from widely different communities in conversation around contemporary crises — is rooted in techniques of radical encounter. Her recent Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education, however, also leverages strategies of audience mobilization. The piece introduces audiences to the parents, teachers, administrators, students, legislators, and civic figures all caught in America’s “school- to-prison pipeline” before requiring that they, too, engage in the conversation sought through all of Deavere Smith’s work.

2016 American Repertory Theater production of Notes From the Field | Source: © Evgenia Eliseeva/American Repertory Theatre

The play exposes its problem in breathtaking breadth, including monologues from Freddie Gray’s funeral, Bree Newsome, Niya Kenny, and Congressman John Lewis. Halfway through the series of monologues — similar in format to Smith’s Fires in the Mirror, Twilight: Los Angeles: 1992, and other landmark pieces — Smith stops.

“Marcus Shelby [the bassist in the piece] and I come from a similar tradition: the black church [ …] call and response […] blues cries, field hollers, work songs, and blues shouts. And we’ve been shoutin’ and hollerin’ up here, and now it’s your turn.”

– Anna Deavere Smith

At this point, audience members are invited to disperse into discussion groups around the theater, where trained facilitators lead discussions and prompt audience members to evaluate their own position in the pipeline.

Structurally and aesthetically, Smith’s ‘Act II’ unleashes controlled chaos. On the administrative side, the discussions stress every capacity of an institutional theater: to even begin the conversations — themselves considerably difficult — theaters must locate/create space for 25 different discussion groups, create a traffic plan, hire and train facilitators, and develop a discussion pedagogy. None of these tasks fit in a theater’s standard repertoire, and require considerable flexibility on the part of staff time and budgeting.

Aesthetically, ‘Act II’ represents an even more radical departure from traditional theatrical structures. Smith herself is a meticulous performer; working with a team of movement and dialect coaches, she recreates her characters with uncanny verisimilitude. And yet, by transferring the spotlight onto the audience for ‘Act II,’ Smith cedes the very control which makes her performances so powerful. The performance — and overall experience — of the second act become radically de-centered, stemming from the participants, facilitator, and circumstances of each particular discussion.

A third type of protest theater breaks traditional boundaries between performer and spectator, incorporating audience members directly into the performance in order to catalyze civic action.

2015 Berkeley Rep production of Notes From the Field | Source: © Cy Musiker/KQED

This chaos is redeemed by its unusual accomplishment. Smith’s monologues are occasionally referred to as “portraits”; each show includes around 20. Yet, in ‘Act II’ of Notes from the Field, the audience glimpses a portrait of itself, framed and animated by the themes of the play. Ideally, in the self-portrait of each discussion group, the audience is able to glimpse the ways in which the issues at the center of the play — widely divergent access to education, incarceration rates, and awareness of the racial imbalances in these intersections crises — are reflected inequitably in the experience of its own members. This glimpse is the kernel of the play’s civic aspirations — showing the audience that they are not immune from the problem discussed, and leaving them in the spotlight long enough to reflect and, hopefully, form a plan for action.

Theater, at its core, requires presence — of both artists and audiences. When theater is able to step out of the echo chambers, into the intersections of culture and politics, this presence grants theater an unparalleled vitality.

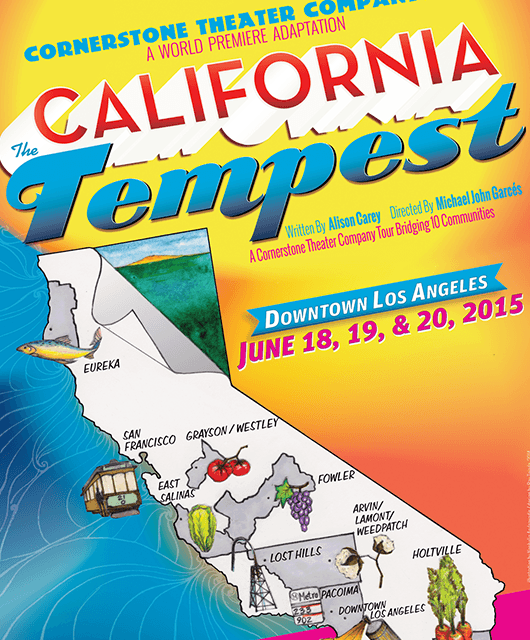

Los Angeles-based Cornerstone Theater Company represents another model for mobilizing audiences to create community portraits resonant with contexts of both classical performance texts and contemporary societal issues. Cornerstone’s mission is to make work “with and by communities,” and they have developed a trademark model for artistic partnerships between theater professionals and other individuals. The company was founded in 1986 as a traveling ensemble led by Bill Rauch and Alison Carey. Zig-zagging the U.S. in a van, the company took up residence in predominantly rural communities around the country in order to adapt classic texts to focus specifically on those communities.

Cornerstone [Theater Company] advances a radically civic vision for contemporary theater: artwork not just for, but by, community members.

Cornerstone’s 2015 adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, adapted for a specifically Californian context regarding water and drought | Source: Cornerstone Theater Company

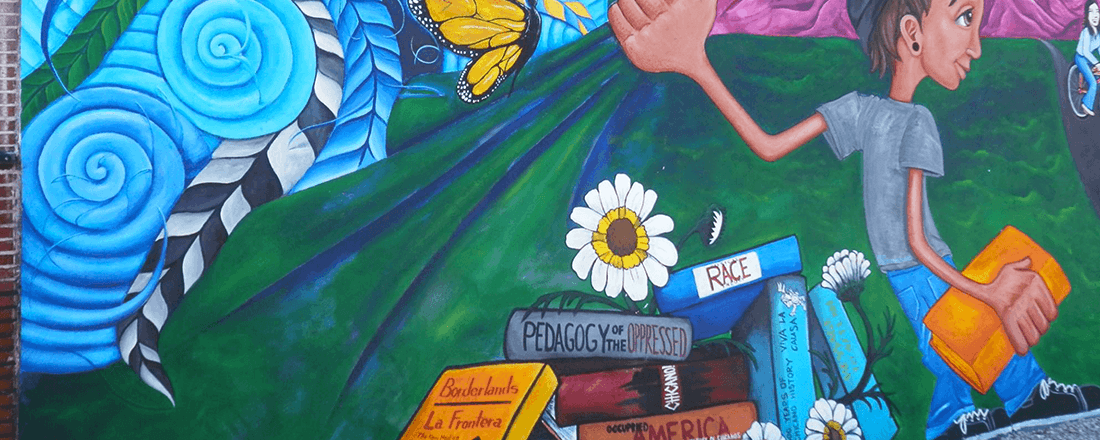

Its focus on communities comes from direct participation: community partners perform in shows, work with the playwright on the adaptation, and contribute design elements. Early productions included a Wild West Hamlet in North Dakota and an interracial Romeo and Juliet in Mississippi. More recent work has included California: The Tempest, performed by ten community casts in ten different locations across California constituting a statewide performance dialogue on water and drought, and The Hunger Cycle, a collection of plays based on different types of hunger (physical hunger, addiction, lack of cultural access) prevalent in communities across contemporary Los Angeles.

Working with their partners in these ways, Cornerstone advances a radically civic vision for contemporary theater: artwork not just for, but by, community members. This approach is both classical and deeply innovative. Cornerstone’s use of community choruses and their positioning of performance as a true communitarian undertaking are reminiscent of Greek theater’s civic processes, from its incorporation into religious festivals through its requirement that groups of townspeople share the responsibility for producing and commissioning the work. At the same time, Cornerstone have done something new in American theater history: their production history consists of a diverse (geographically, linguistically, etc.) portrait gallery of a range of American communities.

Performance opens a civic space where the era radically encounters itself: in the stories on stage, but also in person through language, image, and act.

In this respect, both Cornerstone and Anna Deavere Smith’s Notes from the Field gesture toward a unique model for creating and portraying community. They incorporate audience members deeply into the aesthetic fabric of a performance, in the process eliciting powerful reflections on the relationships between different communities and the texts at hand. The results are wide-ranging: California: The Tempest represents a statewide conversation on water and drought, drawing deeply on the lived experiences and material cultures of communities from carrot farmers in Holtville to loggers and fishermen in Humboldt County; Notes from the Field elicits a collective performance by parents, students, individuals with direct experience of the criminal justice system, and others for whom the experience of all three of these groups are quite distant. In so doing, both performances draw on society to create performance and, in turn, create a civic space expanded and enriched by the theater’s aesthetic and physical possibilities. For both Cornerstone and Deavere Smith, this presence — making a concerned effort both to invite and to recognize a diversity of opinions within the room — is crucial to enacting any type of meaningful protest or reform. As current Cornerstone Artistic Director Michael John Garcés puts it, “Any theater that has a result in mind is not having a conversation.”

Source: Cornerstone Theater Company/Facebook

Shattering

All art is, of course, linked to the political and social conditions of its creation. However, rather than ignoring these ties, the strategies outlined above all — in their way — endeavor to spotlight them. OBERIU deconstructs state language of power and obfuscation; Bread and Puppet Theater and Yuyachkani conjure ghosts hidden by silence; Anna Deavere Smith and Cornerstone Theater Company both place community connections center stage. In all these examples, performance opens a civic space where the era radically encounters itself: in the stories on stage, but also in person through language, image, and act. So embodied and experienced, the demons of a particular time and place — political violence, corrupt policy, deep structural problems — seem closer, and, through concerted effort, within striking distance.