SAMUEL KIM

I cannot keep my eyes off of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s huge protests, explained | Source: © Vox/YouTube

After nearly six months of coverage, most real-time news developments are bound to get lost in the abyss of the 24-hour news cycle, no longer worthy of our attention. They leave us confused and disillusioned. I do not feel that way about the recent unrests.

When a 12-year old was arrested for unlawful assembly, I wasn’t sure what surprised me more — that he was considered a public security threat, or that situations on the ground were so dire that a pre-teen was moved to participate. What began as a peaceful anti-extradition protest has visibly morphed into a fight to salvage the city’s liberal democratic values, the very bedrock of its identity. A quick Wikipedia search of the unrest in Hong Kong gives me a page titled “2019 Hong Kong anti-extradition bill protests.” To call it a ‘mass protest’ is a misnomer, or at least no longer true. And while its former self merely opposed an extradition bill, it is now making demands far beyond what China considers acceptable. The demands are as short as they are concrete and non-negotiable, although no one could pinpoint the leaders that penned them, as if all two million protestors echo the sentiments expressed. The world is witnessing a movement, mounting the biggest ideological challenge against Beijing in three decades.

For the CCP, that day three decades ago did not teach it to prevent a similar tragedy from occurring at all costs. It provided the party with a formidable historical precedent that warns China can crackdown if it so chooses, and benefit from it.

Exactly thirty years ago, in 1989, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) made the fateful decision to authorize the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) brutal crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations sweeping the country. Thousands of Chinese citizens were shot at, stabbed, and beaten to submission by the very people tasked with safeguarding them. As the outside world became incensed by the Tiananmen massacre and moved to tears by the Tank Man, China promptly removed news reporters and party officials expressing similar sympathies. When the smoke cleared, the consequences of this decision must have weighed heavily on the party’s conscience. So much so, that its leaders sought to expunge it from public memory. As the CCP subsequently reinforced a political system that rewards unconditional compliance and an economic system that continues to bring millions out of poverty, Tiananmen seemed to have faded into obscurity: an echo of modern China’s unfortunate past.

Tank Man: hero of 1989 Tiananmen protest stands in front of tanks – archive video | Source: © Guardian News/YouTube

That is certainly not the case now. Media coverage of Chinese army vehicle and troop movements along Hong Kong’s borders last month has gripped Hong Kong and the Western world with fear. Many experts have dismissed these fears as alarmist, but it is apparent that Beijing is flirting with its playbook’s very last resort, a decision to which they owe their current status. For the CCP, that day three decades ago did not teach it to prevent a similar tragedy from occurring at all costs. It provided the party with a formidable historical precedent that warns China can crackdown if it so chooses, and benefit from it. It is this foreboding perspective that I would like to discuss.

Instead of fixating on a narrative that engenders hopelessness, however, I want to talk about a Tiananmen that lived.

This narrative begins with a similar premise on the other side of the Cold War.

The year is 1980. Our setting — South Korea. When General Chun Doo-Hwan seizes power through a coup, declaring Martial Law and becoming President in all but name, protests send ripples through the country. The winds of change in the 32-year old Republic, built on promises of individual sovereignty and democratic process yet to be met, place its new autocratic leaders on high alert. In response, Chun and his men decide to crank up the volume against dissent and stoke the flames of the red scare, forever deterring the idea of regime change. They find a convenient testing ground in the city of Gwangju, Korea’s largest city in the Southwest. Geographically, it is far enough from the capital, and protests are far more vocal in South Korea’s leftist hotbed. The stage is set for policide, or in this case, utter destruction of an idea.

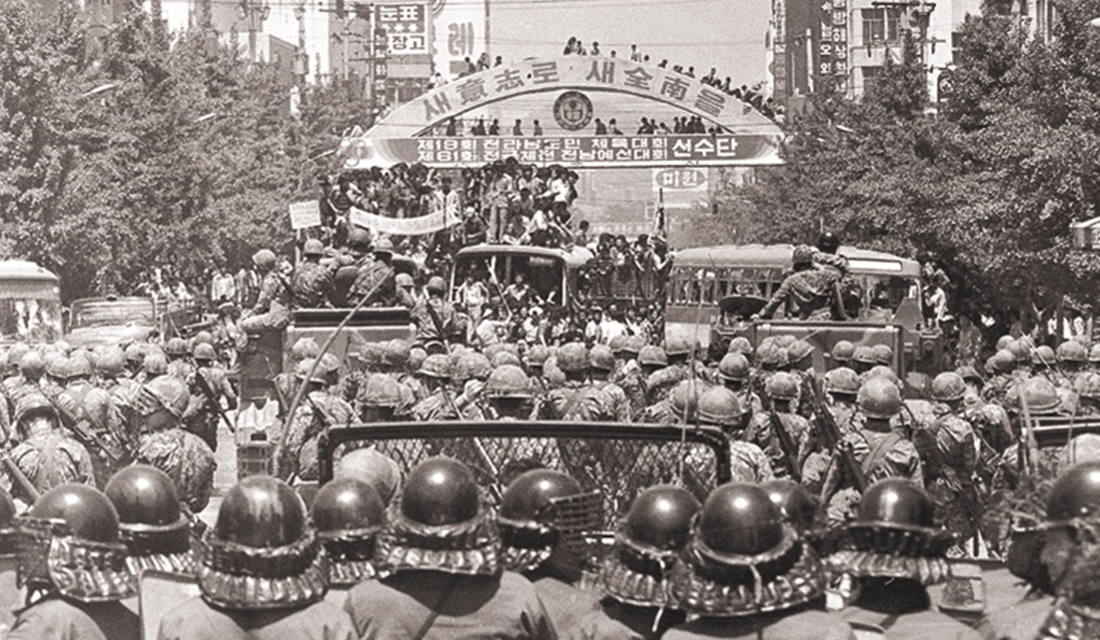

Standoff between Korean military and protestors in Gwangju | Source: KoreaBizWire

Citing the North Korean threat, Chun extended the existing Martial Law on May 17, forcibly closing universities, arresting hundreds of activists and putting opposition leaders under house arrest. Around 300 to 500 Gwangju students protested outside of Chonnam University the next day, only to be shocked by what they witnessed — elite paratroopers deployed there began indiscriminately clubbing and bayoneting the city’s residents. Trained almost exclusively to quell pro-democracy protests, they were effectively unleashed on the crowd. Rounded-up and tethered, innocent civilians were forced onto trucks bound for unknown destinations, many of them never to be heard of again. Hundreds of unjustified civilian casualties, the first among them a deaf man, enraged onlookers, leading to citywide demonstrations. Thousands of citizens poured into the city’s major crossroads, calling for an end to the military dictatorship; their other demands were, in no particular order, the withdrawal of government troops, an end to martial law, and the release of local human rights activist and political leader, Kim Dae-Jung. The government deployed additional divisions to the city, but reinforcements were a pitiful fraction of citizens on the streets, who responded to tear gas and batons with kitchenware, Molotov cocktails, and rocks.

In its quest to restore order in Hong Kong, the CCP has not felt the need to explain themselves, let alone compromise. Every aspect of the government response in Hong Kong proudly mirrors Beijing’s zero-sum approach to dissent. The city’s government, headed by Chief Executive Carrie Lam, has called for law and order but has so far done minimal self-reflection; the police have responded to largely peaceful demonstrators with water cannons, tear gas, and rubber bullets. Even more troubling are the Hong Kong government’s suspected reliance on “extra-legal” governance. The July 21 Yuen Long mob attack saw white-shirted men battering passers-by at random; their metal rods and sticks injured and hospitalized 45 people, including children, the elderly, and a pregnant woman. Hong Kong’s law enforcement accountability took a permanent hit that day, as demonstrators expressed outrage over the delayed police response to the incident, many pointing to it as evidence of government contact with “vigilantes-for-hire.”

When a Mob Attacked Protesters in Hong Kong, the Police Walked Away | Visual Investigations | Source: © The New York Times/YouTube

Yet something is different this time. The movement has eagerly matched a government reaction with an equal and opposite reaction. Armed with sticks, bricks and petrol bombs, citizens fought back against the pro-Beijing triad and riot police. In a desperate move to gain the world’s attention, they paralyzed airport and subway traffic, setting fire to barricades. Some, with U.S. flags in hand, belted out the Star Spangled Banner, even personally appealing to the current U.S. President to pay attention to their plight. And the blowback gets worse for Beijing. Against expectations that the demonstrations will cool off after the new school year, high school and college students skipped their first days to stand off against the police, much to the frustration of the city’s spread-out police officers. The message is clear; just as Beijing will absolutely bury anyone questioning how it runs its people, the movement will not tolerate an adulterated interpretation of the “one country, two systems” enjoyed there. Taking note of this: Carrie Lam’s government officially withdrew the extradition bill, fulfilling one of five demands made, but any celebration from the pro-democracy camp was brief. The consensus among the members of the movement are that of “too little, too late.”

With the unrest in Gwangju seemingly out of hand, the government initially appeared to show an openness to negotiate even the possibility of troop withdrawal. The optimism was felt on May 20 when buses, taxis and trucks honked and moved towards soldiers stationed near the Provincial Hall, surrounded by thousands of cheering citizens. The uprising reached its climax on May 21, as tens of thousands of citizens chanted and sang songs, patiently waiting for the government to act on its considerations. That Wednesday was Buddha’s Birthday; the weather, hot and humid.

At approximately 1PM, the national anthem blared out of the PA system, followed by gunshots. As if on cue, the army opened fire without warning, point-shooting citizens in front of them, for ten minutes.

CBS Gwangju Short with Walter Cronkite | Visual Investigations | Source: James Larson/YouTube

The martial law command reported no civilian deaths. The military was resolving a tense situation with North Korean agitators. The heavily censored state media later reported that the same communist proxies armed themselves, killing several active duty soldiers before they were successfully neutralized. It was an “armed rebellion.” 23-year-old Choi Mi-Ae, an expecting mother with an 8 month-old when she was fatally caught in a crossfire, was not innocent; neither was 7th-grader Bang Gwang-Beom, who was killed by government troops while swimming in a reservoir along the city outskirts. As hospitals were quickly flooded by the critically wounded, many among the crowd that had gathered in front of the Provincial Hall on May 21 met similar fates — succumbing to their injuries and unable to clear their tarnished names.

This blatant lie was propagated to citizens beyond the Southwest, and many accepted this lie for years without much protest. The existing problem of regionalism found new heights, as an entire region’s people — especially the people of Gwangju — became associated with the dreaded label “Commie.” In the years that followed, the state neither mourned the dead nor protected its survivors from such slander.

Rioters. Cockroaches. The “black hand.” The Hong Kong movement has earned these names from either the police or party officials, slurs that harken back to Tiananmen in 1989. In the instances that some demonstrators have initiated violence, the hardline state media has made the most of those footages, describing the behavior of the rioters as all-encompassing. China’s paranoia is further felt when it calls demonstrators in Hong Kong “terrorists” and “foreign agents,” as if the rest of China needed to be protected from an enemy infiltration. In a move to further delegitimize the movement, China has launched a series of subtle but coordinated social media campaigns against the Hong Kong movement, utilizing both official and fake accounts on Twitter. The demonstrators have been compared, among other things, to Nazis, and foreigners present alongside demonstrators have become proof of foreign interference. Little attention is given to how these labels dehumanize the average Hong Konger, justifying any future harm inflicted on them by law enforcement. Even less attention is allocated to the widening gap between the mainland perception of Hong Kong and Hong Kong’s perception of itself.

Nearly forty years later, we have access to resources detailing the unthinkable events that happened next in Gwangju. The city didn’t just fight back; it fired back. Within two hours of the massacre, citizens, many of whom had received mandatory military training, stormed nearby armories for weapons. Following an epic standoff that lasted until sunset, the people successfully drove Chun’s murderous paratroopers out of the city for five full days. Until they were inevitably crushed by the returning paratroopers on May 27, Gwangju was arguably the only place in the country with the right to free speech. On the grounds of the massacre in front of Province Hall, Gwangju citizens held speaker’s events, during which people had the opportunity to reflect on the turbulent past few days. Other, more administrative responsibilities were handled by everyday citizens with grace. Several citizens took the initiative to establish independent governing bodies and helped foreign journalists get the facts on the ground. While masked men conducted traffic stops and maintained public safety, the whole city came together to hold funeral proceedings for the dead and blood drives to save the living. Even as everyday citizens managed roles that the state neglected — the same state that tried to bury the truth by cutting off the city’s phone lines — video footages show the crowd wrapped the caskets in the national flag and frequently sang the national anthem. The irony of Chun, who seized power illegally, considering them enemies of the state was not at all lost on them.

For the past three months, the Hong Kong police has confronted a sea of innominate men and women wearing gas masks. They conceal their faces to protect themselves from tear gas and their identities from inquisitive authorities. The masks also reflect the strength of their beliefs. Pro-democracy activism in Hong Kong has divided friend groups and family members; the wife of an active duty Hong Kong police officer dons it to fight for her convictions without hurting her husband’s career; college and high school students wear them to hide their involvement from concerned parents. Because their views have been thoroughly tested, the movement has exhibited an incredible sense of camaraderie. When 25-year old Jonathan left a message on Telegram requesting those with first-aid training to volunteer, he received 4,000 responses by the end of the day. Between July and August, journalists reported demonstrators donating meal vouchers or food coupons, forming human chains to distribute protest supplies, and leaving transit tickets and small change at subway stations. These acts have earned supporters overseas. After learning about gas mask shortages, Taiwanese national Alex Ko began a donation drive at his local church; he has since delivered up to 2,000 masks, along with air filters and hard-hats. While covering Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella movement, The Independent writer James Legge described the assembled crowd as part of a “commune.” That communal spirit, soon to define an entire generation of young Hong Kongers, is alive and well today.

The message is clear; just as Beijing will absolutely bury anyone questioning how it runs its people, the movement will not tolerate an adulterated interpretation of the “one country, two systems” enjoyed there.

Commenting on the Gwangju Massacre to the Japan Times, University of Connecticut’s Asian history professor Alexis Dudden noted: “Across the 20th-century […] monumental ‘shifts’ have had a first draft played out in Korea with the final copy performed in China.” Reading her quote, I could agree that China’s copy was not unlike Gwangju in the dawn of May 27, 1980; upon reentering the city, the paratroopers fired at the citizens’ army defending Province Hall, reconquering the building within 90 minutes. It was the “final” part that I couldn’t understand — couldn’t bear, rather — because this rebellion was officially renamed the Gwangju Democratization Movement in 1988.

In Han Kang’s novel Human Acts, a former factory girl contemplates the weight of her government’s decision. “The door leading back to that summer has been slammed shut,” she says. “You’ve made sure of that. But that means that the way is also closed that might have led back to the time before. There is no way back to the world before the torture. No way back to the world before the massacre.” Upon winning the presidency after immensely fraudulent elections, Chun sent thousands of political enemies to the military-run Samcheong re-education camp without a warrant, under the guise of a larger “social purification” and gangster mop-up initiative. He then sought to establish its legitimacy by implementing a series of successful economic stabilization plans. Additionally introduced was the 3-S policy, promoting the “sex, screen (film) and sports” industries that were repressed by previous leaders; with the policy as an effective distraction, the Chun regime was able to step up its arrest and torture of human rights activists and their aiders. Any mention of the massacre took place in whispers, for fear of prosecution.

But there was no turning back for Chun, whose presidency was consolidated through a patent disregard for human life. As foreign coverage of Gwangju circulated underground through college campuses, the victims of Gwangju garnered the kind of respect reserved for martyrs, and the uprising gave way to a steadily growing Minjung (people) movement. The movement reached a second boiling point in 1987, when it lost two of its own “martyrs”. College student Park Jong-Cheol’s death by torture and the government’s attempted cover-up made national headlines; a few months later, funeral processions were held for student activist Yi Han-Yeol, who was killed by a tear gas grenade shot directly at him. This time, the pro-democracy crowd was tenfold; millions of Koreans — from Seoul to Busan, Chuncheon to Gwangju — marched in their memory, once again singing the national anthem and waving the Korean flag. It was a decisive moment in constitutional reclamation, one that affirmed the country’s founding principles in Article 1:

- The Republic of Korea shall be a democratic republic.

- The sovereignty of the Republic of Korea shall reside in the people, and all state authority shall emanate from the people.

Defeated, Chun agreed to step down, ushering in an era of direct representation.

Until they were inevitably crushed by the returning paratroopers on May 27, Gwangju was arguably the only place in the country with the right to free speech.

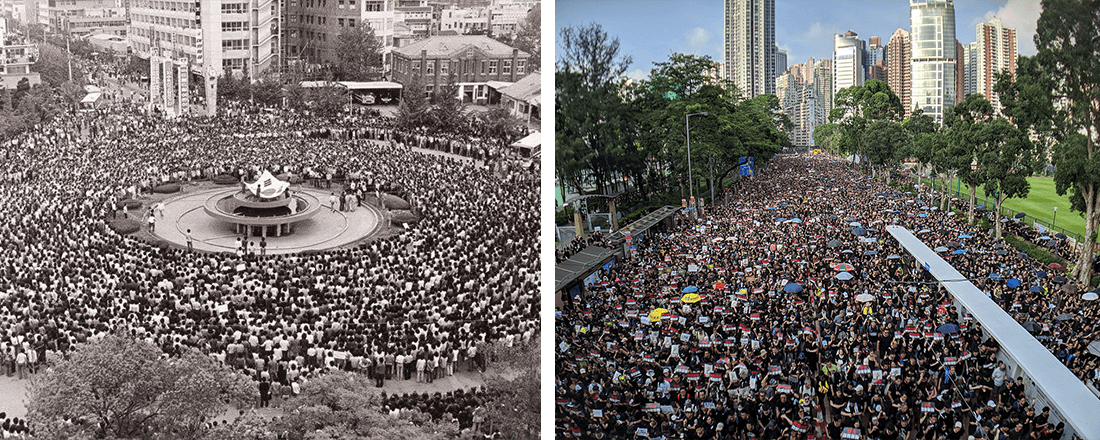

It is easy to compare Hong Kongers going out of pocket to share food and distribute gas masks with the collective action taken by the people of Gwangju. So is juxtaposing recent findings of sexual assault in Gwangju with allegations of sexual violence by Hong Kong police against demonstrators in custody. In 1981, composer Kim Jong-Ryul paid tribute to the Gwangju uprising in his then-censored song “March for the Beloved,” a song which has now become a rallying cry for successive democratic movements in Korea. The verses “as we have gone first / follow us, the living” were heard in Hong Kong during the movement’s earlier months.

(ENG/KOR) A Citizen of Hong Kong Sings A MARCH FOR THE BELOVED (Lyrics) | Visual Investigations | Source: KLCL/YouTube

I wondered if Chun, who was recently on trial in Gwangju for libel against victims of the uprising, ever foresaw the far-reaching personal costs of his orders. I pondered the same for Li Peng, the “Butcher of Tiananmen,” who passed away this year.

What is harder to predict is where Hong Kong’s movement is headed, although we can venture a good guess. Comparing Hong Kong today with Gwangju’s past, I would be remiss to ignore the fact that Hong Kong is not under martial law — yet; fortunately, the Pearl of the Orient has not become victim to another large-scale, government-sanctioned massacre. In no way does the Gwangju timeline run parallel to that of Hong Kong in 2019, but that is exactly what is worrisome. If similarities between the two events are already found on multiple levels, from their dynamics down to the minuscule details, the Gwangju uprising may be a harbinger of Hong Kong’s worst possible future outcome, albeit in the short-run.

As of September 16, Carrie Lam has scheduled a series of community discussions with her constituents to ease tensions, promising that “sessions will be as open as possible,” even though this directly contradicts her advisor Bernard Chan’s recent claims that any further concessions will be unlikely. Does this mean Xi Jinping is finally listening, or is this just a distraction, an attempt to appease the weaker links of the movement? Will the CCP move to crush protestors ahead of its 70th anniversary if unrests continue? Could this be the national anthem before the gunfire?

Most of us — young Hong Kongers included — have not experienced Martial Law or a National Emergency. When the military enforces a city’s laws, will they use real bullets? I could do little other than speculate about the many scenarios involving the Chinese army — disappearing activists, alternative news headlines, piles of dead bodies. As we mull over a looming crackdown, we naturally turn to narratives we are most familiar with to fill in the gaps while we wait. Tiananmen dominates news discussions on what might or might not happen in Hong Kong. The CCP’s constant stonewalling and smug propaganda videos tell us China is fully aware of the fear this instills, and many of us have also taken this warning to heart. Between articles showcasing courage and persistence, I have also followed the stories of Hong Kongers frustrated with what seems an exercise in futility — hoping, instead, to emigrate. There are currently no similar struggles happening on the mainland. When the subject is broached, my friends are quick to predict a clampdown, an opinion also widely backed by our regional experts. The importance of the Tiananmen precedent gives us a good reason to be afraid.

Even less attention is allocated to the widening gap between the mainland perception of Hong Kong and Hong Kong’s perception of itself.

Still, after studying Gwangju, I feel deep down that another Tiananmen-esque military involvement will go horribly awry for those in charge.

Hong Kong protests: China flag trampled in mall unrest – BBC News | Visual Investigations | Source: © BBC News/YouTube

Beijing’s decision thirty years ago has today given it power to deny the past with impunity, and pave the way for its future with minimal obstructions. It can send millions of Uyghur Muslims to re-education camps without much backlash from the International community. It can implement a nationwide social credit system and see the vast majority of people fall in line. That is why Hong Kong’s recent events are so breathtaking. Because while the rest of the world has given these developments a resigned shrug of the shoulders, Hong Kongers are putting a noticeable dent on Beijing’s faith in its own rules.

But paradigm shifts in history do not start with a major milestone. It begins with the belief to see it through. Despite the specter of another military/armed police intervention, I want to raise the possibility that the verdict on the Tiananmen massacre is still out. Many defining moments in history have been triggered by the small things, and I want to believe the extradition bill has lit the fuse for something that lasts, rather than another momentary rumble that died down. Far too many have been affected this summer for that not to be the case. If, like Gwangju, Hong Kong’s movement ends in a crackdown, I desperately want its stories, pictures and footages to capture the imagination of future generations, and shift the window of tolerated public discourse. I believe most Hong Kongers supporting this movement can relate to this desire; it would mean so much more if the rest of China did, too.

That communal spirit, soon to define an entire generation of young Hong Kongers, is alive and well today.

L: Gwangju Protestors, R: Hong Kong Protestors | Source: Asia Society // Studio Incendio/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Which brings me to my final point: what active role could the rest of us play?

Researching the Gwangju movement, my eyes lingered on a particular document in the archives. Addressing the Head of Jeonnam Province’s Maeil Newspaper, a group of reporters left the following message on May 20, 1980:

“We saw it all. We saw dying people getting dragged away like dogs. But not even a sentence about the massacre made it to print. For this, we are mortified and put down our pens.”

There’s an important detail that I left out about Gwangju. Many Koreans still buy the lie, and how someone understands the movement has become a litmus test for South Korea’s left and right. Despite a plethora of evidence disproving claims that North Korea played a role in Gwangju, prominent far-right politicians are continuing their efforts to whitewash the tragedy. The lasting effects Chun’s decision to suppress memories of a massacre has on political socialization is a broad enough topic for a separate article. Without a doubt, Beijing’s heavily-biased, even fabricated coverage will create drastically different narratives in Hong Kong and the mainland, regardless of the movement’s immediate outcome. It is important for the rest of us to be the eyes and ears of this movement from afar if that happens.

The stakes are much higher than we think. Most, if not all, Chinese celebrities active abroad have voiced their support for law enforcement. But it wasn’t until Liu Yifei, an American citizen set to play Mulan in the upcoming Disney movie, proclaimed her support for the Hong Kong police, that I started to wonder if we were entering an era where criticizing China’s actions came at a cost for everyone (the actress may have said it on her own volition, however it is unlikely given the #BoycottMulan backlash she must have anticipated). If China can influence the political discourses in Australia and New Zealand, where a growing number of intellectuals are avoiding frank discussions about China altogether, this may all be a matter of when.

For these reasons, I will not keep my eyes off of Hong Kong.