ALLIE VAN DINE

One of the oldest adages in show business is that “the show must go on!” No matter what little cracks appear in the set, the costumes, or even the actors, the performance must continue.

This adage holds true in one of the highest-stakes areas of international relations: nuclear arms control and nonproliferation. Maintaining unity against proliferation or use of nuclear weapons is imperative — failing to do so doesn’t just mean the show is over, it likely means the world as we know it is as well.

Interactions in the nuclear space are uniquely suited to performance, as they are governed by perception. A state’s ability to act in a world where nuclear weapons and mutually assured destruction make Armageddon possible mean that communicating messages and signaling intentions — in essence, performance — is of the utmost importance.

Nuclear weapons, and the diplomacy that accompanies their existence, are inherently performative.

Theatrical performance exists over thousands of little conflicts — an imperfect or disengaged audience; arguments among the cast, designers, or technical staff; literal rips in costumes or malfunctioning of lights and other equipment. However, when all is said and done, the story is told. This common purpose — telling the story — allows for the performance of unity against a backdrop of these little battles.

This is also true in the case of nonproliferation and arms control. Little conflicts exist at every turn, but everyone is united by one common purpose: continued existence. Every world leader will take actions to ensure the survival of his or her state — as no leader wants to see their country reduced to failure or, in the case of nuclear weapons use, nothing. This fundamental unity — a shared interest in continued existence — has translated to success in nuclear nonproliferation and arms control. Unity against the proliferation and use of destructive weapons is consistently performed over background noise.

Maintaining unity against proliferation or use of nuclear weapons is imperative — failing to do so doesn’t just mean the show is over, it likely means the world as we know it is as well.

The existence of this shared purpose allows us to usefully consider nuclear arms control and nonproliferation through a performative lens. Action in both spheres is guided by the vision, goals, and parameters defined by an outside presence: in the case of traditional theatre, the director; in the case of arms control and nonproliferation, the ever-present imperative of state survival. These entities provide varying levels of guidance, direction, and definition, but their presence always influences the choices actors make. In both worlds, actors do not represent themselves as individuals; rather they serve as symbols of broader ideas. In theatre, this is the character as laid out by the playwright and artistically defined by the actors and director. On the international stage, this is the nation, organization, constituency, history, philosophy, or principle represented by each actor.

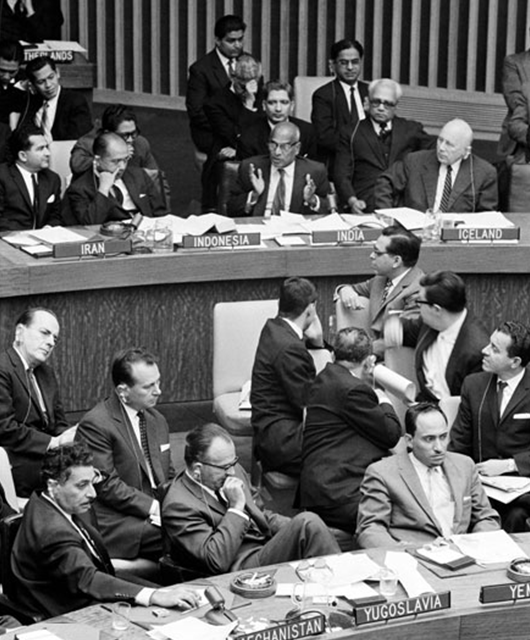

UN Meeting discussing the merits of a nuclear test ban in 1961 | Source: © UN Photo/UN Audiovisual Library of International Law

These actors include heads of state, military leaders, chief diplomats, parliamentarians of all stripes and the national publics and constituencies they (purport to) represent. Also included are representatives of international organizations. There’s the media, both international and national. The international stage is a crowded one, and the millions of interactions that take place each day among and between these actors weave a very chaotic tapestry.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, art is a uniquely human creation, and politics a uniquely human activity. Bringing human creation to bear as a medium through which to interpret human interaction is in and of itself a useful, often revelatory undertaking.

In this essay, I will highlight three recent examples of performances of unity in the world of nonproliferation and arms control: the 2015 Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference, the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (colloquially, “the Iran Deal”), and recent North Korean nuclear tests. Each of these highlight different forms of “unity” in the international space: the first, a treaty, the second, an agreement, and the third, an alliance.

I will reference two different “unities” throughout. First, there is what the Merriam-Webster dictionary calls the “simple” definition of unity — “the state of being in full agreement.” These little unities are performed to telegraph secondary or tertiary goals, to pursue state interests of less importance than the ultimate goal of survival. Then, borrowing from the full definition, there is what I will call Unity — “the quality or state of being made one,” “a totality of related parts.” “Harmony” would be too strong a word here, for the idiosyncrasies and unpredictabilities and little moments of pettiness that characterize leaders and states preclude such a peaceful state.

The imperative to avoid nuclear Armageddon — to survive — makes all actors in this space One. It is the thread that connects them into a totality of related parts. It is the story they have to tell, the fundamental purpose they all share. Survive. See what tomorrow brings.

In short: the show must go on.

April 2015: The Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference

The year, 2015. The place: a cavernous hall in the United Nations.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry addressing the crowd at the 2015 Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference (RevCon) | Source: U.S. Department of State/Flickr

After a month of debate and discussion, representatives sent from governments all over the world to the quinquennial Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference to decide how to further implement the treaty returned home empty handed. No consensus had been achieved.

First, you may be wondering — what is the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and why does it need a Review Conference (RevCon)?

The NPT is, in fact, one of the best examples of international unity against nuclear weapons and nuclear proliferation, and is premised on an essential grand bargain: the five countries (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) that developed nuclear weapons before the treaty was negotiated get to keep their programs. They are referred to as nuclear weapons states (NWS). Everyone else waives their right to nuclear weapons. They are referred to as non-nuclear weapons states (NNWS). In exchange for accepting this status quo, NNWS can receive technical assistance from the NWS on peaceful nuclear energy programs, and the NWS promise — in the treaty’s infamous Article VI — that they will one day eliminate their nuclear weapons stockpiles, leaving a world without nuclear weapons. The treaty has over 190 signatories, and is as close to universal as one can get when it comes to treaties.

First Meeting of the Review Conference (RevCon) in 1974 | Source: © UN Photo/UN Audiovisual Library of International Law

Treaties are an interesting performance space for unity, as they are highly structured. They have international legal standing and incur obligations once ratified and brought into force. Unity is implied — in signing on to this, states commit to making it work. No matter what tensions arise or cracks emerge, everyone takes a nice photo and promises to try again. In that sense, it is a bit improvisational — participants have agreed to rules, and will perform to achieve their objectives within an existing framework. The stakes are high, but not so high, as the framework prevents catastrophe.

Observers were thankful for this safety net as the 2015 NPT RevCon — closer to spectacle and circus than Tony Award-winning drama — dispersed with no consensus document to outline steps forward on global nonproliferation. While disappointing, this was not unanticipated; before the conference, U.S. messaging was already preparing the world for a failed RevCon.

U.S. President Barack Obama speaking in Prague | Source: The White House

This was not a surprising performative choice, given the parameters within which the United States was acting. President Obama’s famous, Nobel Peace Prize-winning Prague Speech — which outlined an agenda promising American leadership on nuclear disarmament, nuclear security, and nonproliferation — had been badly beaten up by an internationally belligerent Russia and a domestically belligerent Congress. This was compounded by efforts to modernize nuclear stockpiles at home and abroad, which complicated how allies and enemies alike viewed NWS commitments to disarmament. As a result, despite important groundwork laid on international nuclear disarmament verification and the ongoing negotiation of what would become the Iran Deal, the 2015 RevCon commenced against a backdrop of less progress than originally anticipated.

Treaties are an interesting performance space for unity, as they are highly structured.

The monthlong RevCon was performance at its finest — dramatic declarations of disappointment and dissatisfaction, indignant rebuttals, and impassioned pleas for recognition of the horrific consequences of nuclear weapons, the threat they pose to humanity, and how this inherent cruelty should render their existence illegal. It was at once a political drama, heart-wrenching tragedy, and a dark and dissonant buddy comedy.

History, however, provides hope. In the 1990s, Unity was performed over a cacophony of unities. 1990 saw a similarly chaotic RevCon and no ultimate consensus. But by 1995, larger purpose had prevailed and the actors had once again found their direction. The 1995 RevCon achieved consensus, and indefinitely extended the NPT as a forever-performance of international Unity against nuclear proliferation. We may well see a repeat in 2020.

The show goes on.

July 2015: The Iran Deal

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“the Iran Deal”) provides another example of Unity performed over many conflicting unities. This time, though, there was no safety net of international law. Performance was crucial to convince a variety of audiences of the deal’s merits.

Unity is decidedly more difficult to perform when not every audience shares the same basic knowledge of the play’s contents, or attends the play with an entrenched, unchangeable view of its merits.

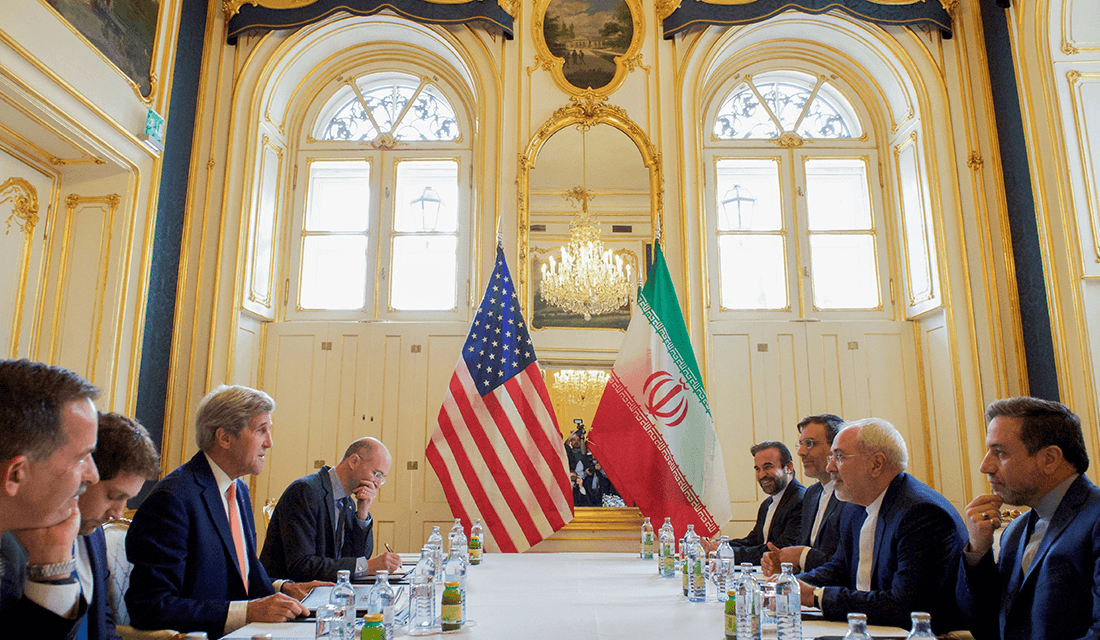

Representatives of the states involved in the “Iran Deal” | Source: Dragan Tatic/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

The Iran Deal was a work of international art, and therefore went on the ultimate international tour. This collaborative piece emerged from intense multilateral negotiations among friends, enemies, and “frienemies” — China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Iran, with input from the International Atomic Energy Agency. The performance of this unity alone is in itself remarkable — especially considering the increasingly tense U.S.-Russian relationship, uneasiness between the United States and China, and the outright hostility between the United States and Iran.

What was particularly interesting and unique about the Iran Deal performance was that each audience arrived with a different set of information. In Iran, information about the deal was completely state-controlled. Americans, on the other hand, were inundated with fact sheets, opinion pieces, and “hot takes” from every angle. The average American probably was not even watching the drama unfolding in front of them, preferring instead to focus on the comedies and tragedies of daily life. Those who attended the performance often did so with an entrenched opinion. Americans focused on the possibility of Iranian cheating, Iranians were concerned about the opposite. Europeans focused on the U.S. Congress to see whether or not it would completely destroy American credibility by preventing the implementation of an agreement that, since not a treaty, did not require their “advice and consent.” The world waited in suspense to see how Israel would react.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif discussing the implementation of the deal | Source: U.S. Department of State/Flickr

Unity is decidedly more difficult to perform when not every audience shares the same basic knowledge of the play’s contents, or attends the play with an entrenched, unchangeable view of its merits. With no safety net, the stakes for this performance are incredibly high — there is no guarantee that states can “try again.” And yet, these seven entities that rarely agree on anything performed convincingly, both individually and as an ensemble. Iran Deal lives and implementation has begun.

The show goes on.

North Korean Nuclear Tests

Performing national power has historically been a route to achieving national unity.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un | Source: © KCNA/Reuters

Performing on the same stage as North Korea in a play about North Korea is like trying to act alongside Liberace in a play about Liberace — one is up against a master showman.

When it comes to “performance” in the nuclear space, there is perhaps no country more performative than North Korea. North Korea performs for two reasons: to project the power it craves, and to convince its starving and impoverished citizens to unify behind a government that does not prioritize them. Performing the role of Great Power inspires and perhaps makes people forget the ache in their bellies, the disappearance of friends and family in the night, and the brutal regime under which they live. Performing national power has historically been a route to achieving national unity.

Kim Jong Un next to what the North Koreans say is a miniaturized silver spherical nuclear bomb | Source: KCNA/Wikimedia Commons

Recent provocative nuclear tests and a once-in-a-generation Party Congress provided the perfect stage for North Korea’s performance of national unity. And the world has responded with its own performance, strengthened by China’s participation in key United Nations Security Council (UNSC) sanctions. These are something China could have vetoed; the fact that North Korea’s closest ally chose to punish it, even if only from the relative safety of the ensemble, sends a powerful message.

The interesting part of this performance, however, takes place within the U.S.-South Korean alliance. In addition to unifying at the diplomatic level via sanctions and statements alike, the countries deliver their strongest performance via joint military exercises. This year’s exercises — involving 300,000 troops — are the biggest in the history of the alliance, and are augmented by U.S.-Japanese-South Korean missile defense exercises. These actors perform antagonistically to communicate a single message: despite North Korea’s bluster, they are not the Great Power they so badly wish to be. This reminder infuriates the North Korean regime, which has demanded a cessation of military exercises as a precondition to denuclearization talks. The alliance, meanwhile, demands denuclearization as a precondition to cessation of exercises. So here we are. Will Liberace exit, stage left? Or will the theater crumble around him?

The show — for the moment — goes on.

[Author’s Note: The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and do not reflect those of the Nuclear Threat Initiative or its board.]