MARIA MILLER

For many of us, this was our first real election.

Us being millennials, coastal, and college-educated twenty-somethings. It was the first time we were engaged in an election; the first time we really paid attention, where we understood the stakes. Even for those of us who’ve cared deeply about politics for a long time — poli-sci majors and election math nerds — this one was special. I live in Washington, D.C. and work in congressional politics — the humid and corrupt “Swamp” Donald Trump seems so eager to drain — and my job depends on someone winning a tight and unpredictable election every two years. A decade before I could legally vote, I remember reading about each city council and state legislature committee aloud to my mom while she filled out her mail-in ballot. My first vote in a presidential election was for Barack Obama in 2012, and I’ve never felt the same breathless joy as when we sprinted down to the White House when they called his re-election (to be fair, I was also very out of breath). And yet, this one election felt different — deeply significant and personal. It felt like ours.

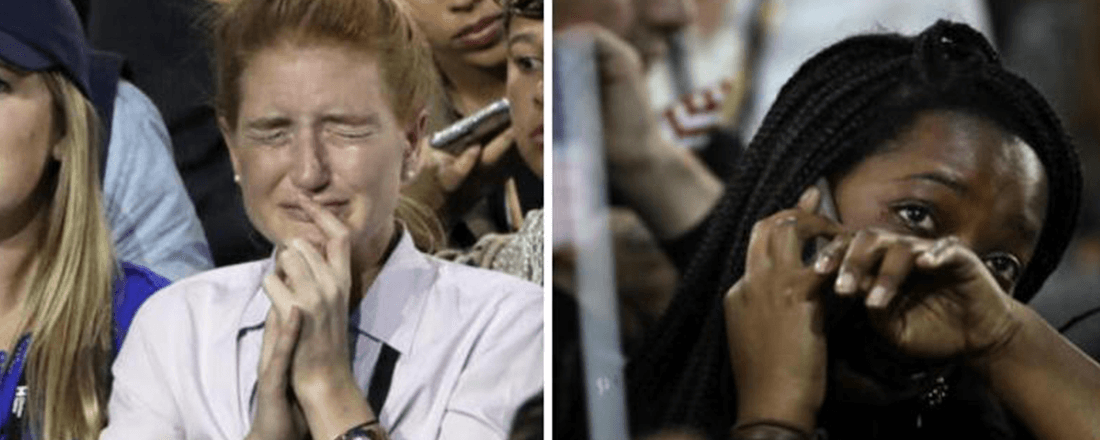

Reactions to the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election Results | Source: © Deccan Chronicle

Certainly part of it was our age; the first time we were forced to imagine a life without the Obamas in the White House; our first real paychecks making us care about taxes. Social media played a significant role, allowing us to retweet and live-stream and engage in the two-year election circus through the mediums in which we spend a lot of our times on. And, of course, the candidates: fired up about Bernie Sanders and fighting for him until the bitter end, or finding hope in John Kasich, tucked in the backseat of the clown car of the Republican primary but seemingly sane. And, of course, Hillary Clinton — the first woman with a real shot at winning the White House; who we followed on Snapchat; who our parents told us they didn’t trust but we couldn’t understand why. We cried watching her campaign videos, participated in text canvasses from our apartments, shared article after article about why Hillary was the BEST and Trump was the WORST. We were just so sure that we were seeing the first fissures in the glass ceiling, and that Hillary Clinton would be our next president. How could she not be?

Hillary Clinton during her concession speech | Source: © ABC News/YouTube

And here in the Swamp, we were just as certain. And just as deeply shocked by the results of the election. “How did this happen?” we demanded of each other, as we watched the returns from Florida and Michigan and Ohio come in, and as we slowly put away the celebratory champagne. “What happens now?” we wondered on the 9th, when we woke up and scrolled through Twitter. “WTF? WTF? WTF?” we texted co-workers as we boarded planes back to D.C. from Ohio and Nevada and Missouri, where we’d taken leave to spend two weeks knocking doors and making phone calls. In a city where 91% of the population voted for the candidate who lost — a city built around the business of winning elections — nobody had seen this coming.

But we should have seen it. We should have known. Unlike many of our coastal, liberal, urban elite peers, we are deeply aware of the rage and resentment seething in places like Ohio and Michigan and, really, most of the country. We know because we spent a summer when we were 22, answering their phone calls during our unpaid Hill internships. They are the first to raise their hands in constituent town halls. These people don’t account for the whole chunk of the country that voted for Trump — that group included lots of people who had never before engaged in the political process. But we should have been clued in. We thought we knew what the country wanted and that they’d agree with our beliefs about their best interests. We were wrong.

A lot of people reject this claim — that we were wrong and made a mistake. “The popular vote!!” they tweet. They say the electoral college and voter suppression — not failed messaging or policy or outreach — are to blame. The system is broken. There’s no point in caring because the worst imaginable thing has happened. “Fuck this,” or, “we’re fucked.”

But what if we don’t disengage and go back to business as usual? What if we hold on to the passion we felt as we donned our pantsuits and refuse to forget how awful Wednesday morning was, and use that to fuel a continued engagement with the very system we feel betrayed us? What if we keep believing in the system, and fighting within it as well as from the outside?

I suggest this because in spite of how terrible I felt on the morning of November 9th — how scared each Cabinet nomination and typo-riddled and hate-filled 3 A.M. tweetstorms makes me — I still believe in the system.

It’s hard to explain why. I still trust a system that is so clearly flawed, that contributed to a climate of resentment and rage throughout the country so strong it caused people to choose an offensive and unqualified “outsider” over our beloved candidate.

I know I believe in the system’s people — this people of the Swamp and those around the country, who have fought and continue to fight because they believe it will make a difference. The policy experts who’ve worked under three or five or ten different cabinet secretaries, putting aside their political allegiances in order to continue the work on climate change or technology policy or children’s healthcare to which they’ve dedicated their lives. The legislative directors in congressional offices who work crappy hours for a quarter of what they could make in the private sector. The college grads from around the country who move to D.C. to compete with thousands of others for a staff assistant job — where they make $28,000 a year — because for their whole lives they’ve wanted to walk to work every day in the Capitol building. Caseworkers in congressional district offices around the country who are helping veterans receive their benefits and the elderly navigate a behemoth Medicare system. People on both sides of the aisle who are painfully aware of the system’s flaws, with its frustrations and inadequacies, and yet still believe in it and our capacity to make it better.

And I am able to believe in the system, certainly, because I benefit from it. I am in a position of privilege — white, an American citizen, well-off, educated, with the right kind of last name — that protects me from experiencing the worst of what these next four or eight years may bring. I am biased by my privilege. Privilege that allowed me to work an unpaid internship instead of a part-time job. Privilege that gave me a resume that got me in the door for an interview my first job and every job I will have for the rest of my life.

And yet, while trusting the system is difficult, the alternative choice — giving up, disengaging, forgetting how it felt to believe so strongly — seems so much worse.

My father wrote in an email to me the day after the election that “we had the same feeling of dread when Reagan was elected in 1980.” At first, I pushed back; no way. This is much, much, worse. And perhaps it is — certainly Ronald Reagan never tweeted so boldly, and so baldly denied facts. What would we give now for a Reagan in the White House. But the truth is that our disappointment is not the first of its kind and will certainly not be the last. The risk of continuing to care — to fight and remaining engaged — is that you’ll be beaten and disappointed again and again.

It may not be enough. The system may be too flawed, with power held by too few. It may make no difference however many calls regular people make to their congresswoman and however many doors they knock on for a city council race. But what if it’s not? What if steady and intentional action by individuals can have an impact? What if a continued focus and commitment can prevent another disappointment, and therefore make this one bearable by making it temporary? I think it might.

I still trust a system that is so clearly flawed, that contributed to a climate of resentment and rage throughout the country so strong it caused people to choose an offensive and unqualified “outsider” over our beloved candidate.

From the perspective of a swamp-dweller, here is how a regular person can contribute a portion of their two most precious and limited resources — time and money — towards participating and shaping our country’s government.

Learn the Names of Your City Council Members and Your State Representatives and Senators

Pay attention to the names down the ballot for the school board and the utility board. Follow them on Twitter and subscribe to their monthly newsletters. The reasons for this are twofold.

First, those who govern at a local and state level have a much more significant — and much faster — impact on the everyday lives of their constituents than anyone higher up. Obamacare helped millions of people around the country, but it took millions of dollars, immense press coverage, and time. In contrast, Ohio’s new six-week abortion ban was signed into law after being on the public radar for only one 24-hour news cycle. This year, the Arizona state legislature reinstated the Children’s Health Insurance Program and within weeks, 30,000 kids had insurance — just like that.

Second, the people elected at the bottom of the ballot move up — and quickly. This year’s state representative is next year’s state senator, then U.S. Congressman in a couple cycles, then a Senator down the road. Start paying attention now so that you’re not shocked in ten years when your home state’s new Senator goes against everything you stand for.

And if you live in New York or San Francisco or even here in the Swamp? Then start paying attention to the town where you grew up, or where your grandmother lives. Read a local paper. Start paying attention to places different than where you live. Not because they’re where “real people” live, but because people there matter. And they vote — in higher numbers than the people “like us” do, or at least did this election.

Next, Engage with Your Elected Officials at Every Level

Few people realize how easy it is to communicate with the offices of the people making the decisions. Call them and send letters, yes, but also tweet at them. Social media is a public way to communicate with your representatives and you generally receive a timely response. Take to the Internet to thank them; ask for an explanation; urge them to vote a certain way. Be polite. Remember that for the person answering your recorded phone message or responding to your tweet, this is their job. And even if you’re represented by someone you completely disagree with, try to find one thing about which you actually do agree with. I can almost guarantee there’s something on their website — a plan to get computers into classrooms or a commitment to helping veterans receive mental health care. Get yourself invested in that. Not because that’s all you can expect of them, but because it’s something. Make sure they keep up that one good thing while you start the work of unseating them next cycle.

Which Brings Us to the Next Point — Start Looking Forward

There will be at least 33 Senate seats and all 435 House seats up for election in less than two years. About 10 of those Senate and 40 of those House seats will be competitive, meaning a strong challenger could flip it from red to blue, or vice versa. These races will start up in the next six months. Start paying attention now.

And then start paying with money or time. Lots of smart people have already said this, suggesting contributions to Planned Parenthood and the ACLU, to combat the women’s and civil rights infringements which are all but guaranteed to occur over the next four years. Take that a step further and start investing in next cycle’s races. Find the activists who will run for city council, the state senators who’ve managed to make real change who might run for an open House seat. Contributing $5 or $15 or $150 to their campaign makes more of a difference than signing five thousand online petitions. Money wins elections because money buys ad time and pays organizers and prints mailers. If you object to the role of money in politics, then find the candidates who do too — and commit to knocking on fifty doors or making one hundred phone calls during their campaign.

Protest against the President-Elect | Source: © Democracy Now!

These steps may feel futile, or daunting, or exhausting. They will not guarantee that things get better, immediately, or ever. For those of us who love measurable impact, calling legislators and participating in phone banks will be disappointing. But there is the small but real chance that by starting now, you can influence the outcome of a future election and have a hand in the choosing of future decision makers. It’s a possibility that I find hopeful and quietly reassuring and far more appealing than any other option.

This was our first election. But what if it’s not our last?