DANNY RIVERA

Realistic fiction bores me.

Maybe that’s too strong.

Left to my own devices, I’ll probably spend my time with science fiction or fantasy before I dive into any grounded human drama. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not discounting the value of that kind of work, but I don’t hold it in the same irreproachable esteem as some of our most venerated institutions do (the Oscars haven’t felt relevant to me since The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King won Best Picture in 2004). As an actor, however, it’s an entirely different story, of course: my favorite genre to perform in is that very kitchen-sink, meat-and-potatoes, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams family drama type. As an audience member, though? They kind of leave me flat. Why?

To put it simply, narrative distance. My responsibility when performing is to dive into the material headfirst — but not as an audience member; I need a little space. If I’m too close to the action, the dramatic, fictional value is gone. It ceases to be entertainment and comes very close to being news. This is not inherently a bad thing but — for me — it’s something I can only digest in small doses. I need a filter to allow the text, the world, and the people of whatever fiction I’m consuming to speak.

Source: © Kyle Lambert/Netflix

And I don’t think I’m alone in that regard. There’s a reason Game of Thrones is so popular (its most recent season was its highest rated yet), why Stranger Things is so popular (its first season is one of Netflix’s most watched), and why Star Wars is such a popular franchise (seemingly more so now than ever). Granted, realistic fiction is popular, too — of the top 100 most watched shows on TV in the 2015-2016 season, only 16 were science-fiction, horror, or some other non-realistic genre — but the point is there’s something to the aforementioned shows/movies beyond swords, alternate dimensions, and spaceships.

What continues to draw us to these shows and these movies? Is it just escapism? I don’t think so. I think these genres — these worlds — allow us an opportunity to explore ourselves and our humanity in a vacuum. They’re the independent variable in a social experiment of sorts. We have no distractions, no frames of reference, other than ourselves and the question, “What if?”

When you give your audience fewer opportunities to check your world against theirs, they’re more likely to buy in and give all their attention to your world.

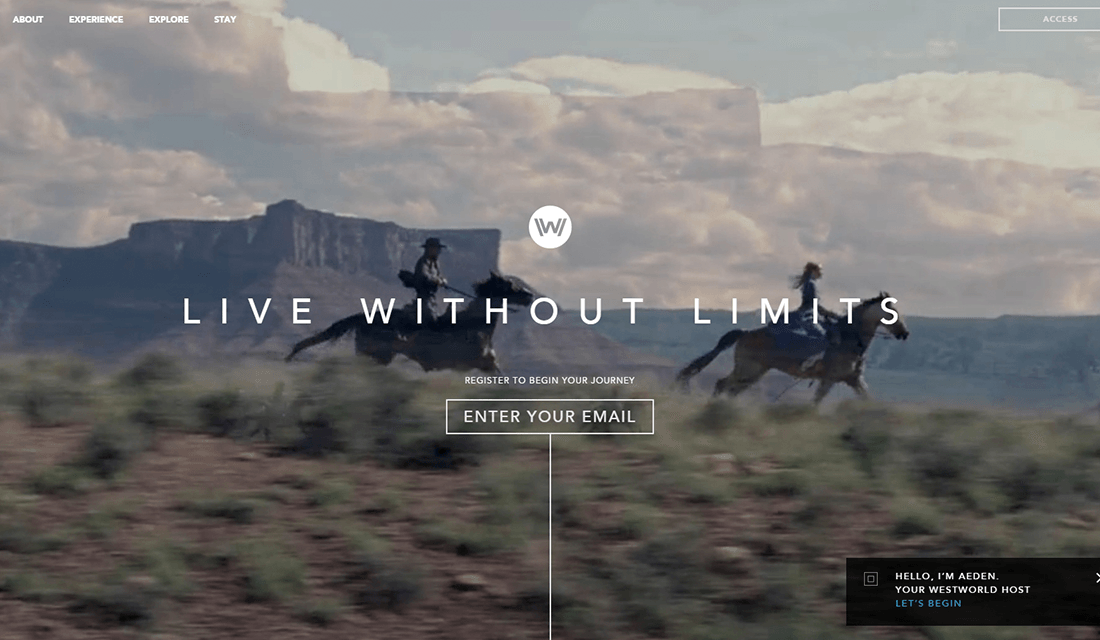

Think of Westworld (specifically the recent HBO version and another massive hit for the network): the entire premise of its titular amusement park is the question, “What if there were no rules?” What if you were allowed to run free in the “wild” of the Wild West? Admittedly, that was more of the backdrop to an exploration of the show’s internal mythology, but that backdrop was used to great effect in pulling viewers in. And that same backdrop is why we play video games, isn’t it? To make choices in a world free of consequences?

Discover Westworld, a website created to allow real-world viewers to experience what the characters in the show experience as they signed up to visit Westworld | Source: Discover Westworld

Sword Art Online asks that very question. (For the purposes of this discussion my experience is tied directly to the anime from 2014.) Set in the 2020s, Sword Art Online sees a world where players can now fully immerse themselves in a virtual world, projecting their mind through a device to control a character with their thoughts (Think Westworld, but instead of physically going there for an exorbitant fee, you’re lying on your bed with a helmet on. Y’know, the future). The story’s twist, however — don’t worry, no spoilers; this is just the premise — is that on the day of the game’s release, every player in Sword Art Online (the name of the show and the game in question) gets trapped in the game — or rather, their minds get trapped. Removal of the device in the outside world, or death within the virtual world, results in instant, real-world death.

Kirito from Sword Art Online | Source: pep anime/YouTube

The show’s main character, Kirito, is forced to grow outside himself. A recluse obsessed with games and withdrawn from his family, Kirito learns throughout the show that if he’s going to have any hope of completing the game (the condition for freeing everyone from the trap), he’ll need to work with — and grow close to — others. Refusing to believe their circumstances and playing as if it were still a game — or even embracing their circumstances wholeheartedly — some characters go so far as to actually kill other players. Some others, when confronted with the gravity of their situation, refuse to “join the front lines” and play the game as intended. They choose simple lives as shopkeepers, as teachers, as fishermen, and wait for others to clear the game. Some others still commit suicide.

When a story asks “what if?” in a situation few of us can ever lay claim to experiencing, we all sit forward. We all have our opinions, we’re all engaged.

Sword Art Online | Source: GIPHY

The context of this game/show accesses something very real: the fear of death shapes our entire lives. A world of no rules and risks like a video game world results in a multitude of behaviors that are suddenly reckless, dangerous, and wrong once death becomes all too real. Beyond that, the show traffics in little, intimate moments that only highlight this idea, putting the meaningful things in life in sharp relief by having them take place in a fictional world of armor, swords, and dungeons. Without the fear of death, who in this virtual world would give a second thought to taking a nap, sharing a meal, or even finding love? Faced with genuine, real-world risks, however, the characters of Sword Art Online are stripped bare, exposing what’s important to them.

Sword Art Online | Source: GIPHY

What Sword Art Online accomplishes thematically is the same as what it does structurally: it strips the audience of any real-world distractions. Sure, its premise is an extrapolation of current technology, but it carries that idea so far as to allow us to purely wonder “what if?” No, it doesn’t go as far as, say, The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit with their elves and dwarves and wizards and orcs and so on, but it’s no less effective. Nor is that to say that human protagonists are any easier to identify with than those of different races. I once wrote that my favorite part of the recent Warcraft movie was the relationship between the Orcs. Further still, we in no way needed a new franchise inspired by The Planet of the Apes, but we have one, and it’s good (so far) — even going as far as to begin a debate as to whether the lead actor should be nominated for an acting Oscar (he shouldn’t). Once you suspend disbelief, anything’s possible: apes can talk, orcs are more interesting than humans, and a dwarf and an elf can be friends.

Friends | Source: GIPHY

By way of contrast, people who watched Friends refused to believe the characters had so much time to sit around and drink coffee all day. The point being, when you give your audience fewer opportunities to check your world against theirs, they’re more likely to buy in and give all their attention to your world. You could drop them in wholesale like with The Lord of the Rings or Warcraft, or slowly peel the world away like Sword Art Online but — either way — you’ve got to pull them in. (For more about world building best practices, read this other thing I wrote!)

It’s harder to be engaged when fiction is based on a true story, or just grounded in reality, because those choices were made, or made in a world like ours by people like us. You can be moved, and you can appreciate the choices, but that speculation-driven engagement is limited.

Like Sword Art Online, The Magicians (both the novels and the television show) dips a toe in a new world before diving in headfirst — and it traffics in the very ideas we’re talking about. The protagonist Quentin Coldwater is obsessed with books set in a fantasy land, feeling wholly disconnected from the real world. All of a sudden, magic comes flooding into his life and he has to keep up. The Magicians isn’t just about that wish fulfillment, though. I found myself longing for the world in The Magicians, yes, but if that’s all I felt, it wouldn’t be as effective a piece (or pieces) of fiction, would it? I wouldn’t have binge-watched the first season nor eagerly consumed the novels as quickly as I did. Yes, there is the purely escapist factor, but this isn’t just some “Hero’s Tale” where you can easily step into their role and live their life. The protagonists (not just Quentin) are genuine, flawed people. So invested are you in the circumstances of their world, at the opportunities presented to them that you can find yourself arguing with them over their choices. “How could you do that?” you scream. “What is wrong with you?”

Source: © SyFy

Thanks to the beauty of internal monologues, we know what’s “wrong” with them, but that’s not why we ask that question, is it? When asking, “Why?” and “How could you?” what we’re really saying is, “That’s not what I would have done.” Oftentimes we don’t even realize that’s what we mean. We’re hit, we’re affected, and we respond. In one particularly frustrating moment in the second book of The Magicians trilogy, The Magician King, I actually threw the book aside. (Sorry, book.) Beyond the fact that the story is genuinely effecting, what makes the book or the story last in your mind and your heart is that tension between what happens and what we would’ve done.

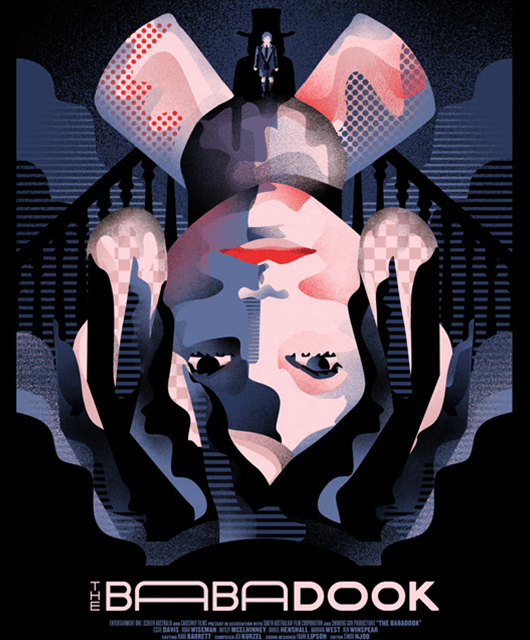

Poster by artist-duo We Buy Your Kids of The Babadook | Source: © Mondo

This tension is a fundamental truth of horror movies to the point of being a joke: “Don’t go downstairs! Don’t investigate the noise! Get out of the house!” These are tropes that many horror movies need to function at all, but the fun is in that tension. The delight is in knowing, “Oh no, I would never do that,” then feeling vindicated when the “dumb” character in question is eviscerated in some predictable way. The true horror is in those movies where there are no options — like in The Exorcist or The Babadook — where running isn’t an option, because a mother isn’t going to abandon her child.

But that’s what choice does: when a story asks “what if?” in a situation few of us can ever lay claim to experiencing, we all sit forward. We all have our opinions, we’re all engaged. It’s harder to be engaged when fiction is based on a true story, or just grounded in reality, because those choices were made, or made in a world like ours by people like us. You can be moved, and you can appreciate the choices, but that speculation-driven engagement is limited. The overlap between the story experience and the audience’s experience is smaller in these stories. The flip side is that there’s a demand for more stories about more experiences — and that’s a good thing.

There’s value in those kinds of stories: they can raise awareness for real-world problems, they can uncover untold histories, and they can move while doing so. For my money, however, they can’t engage me the way something a bit more fantastical can. They can make me feel like a passenger when I want to thrill at imagining my hands on the wheel. They can make me feel like a voyeur. For me, there’s a time and a place for that, and it isn’t so often that it means they’re my go-to type of fiction.

Maybe that means I have “bad” taste. Maybe it means I appreciate “movies” versus “films.”

Or maybe not. Maybe there’s a sweet spot in the middle where my favorite fiction lies: the kind that provides a safe space to explore things I would otherwise hesitate to. Ultimately, there is no right or wrong way to consume fiction, nor is there a genre above the others. But each of us has those things that speak to our heart, that we come back to more often than others — and for me, those things lie through the looking glass, down the rabbit hole, and on the other side of the wardrobe.