SARAH GRACE VILLARREAL

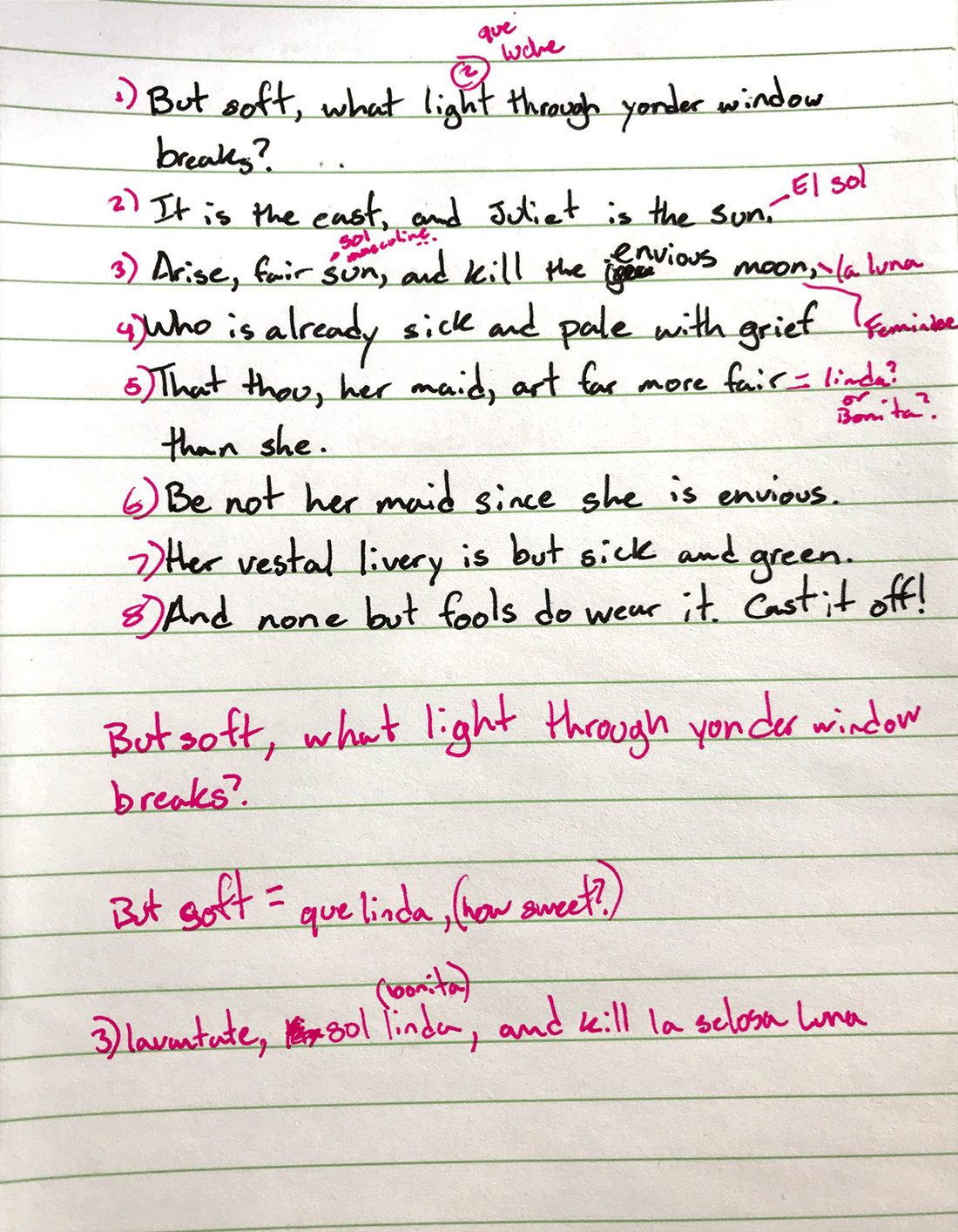

Whatever made me delusional enough to think I could successfully translate Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into Spanglish quickly vanished once I made it through about half of the translation. I’m not fluent in Spanish, and even if I were, it would be a San Antonio dialect — which, I’m sure, many native Spanish speakers would turn their noses up to. Nor am I fluent in Spanglish. But what constitutes Spanglish? I’m sure everyone’s form of Spanglish is a little different and mine is the shameful kind of a second generation American-Latina who has not learned the language of her ancestors. My Spanglish consists of saying things like chancla for slippers or flip-flops, and a few phrases like yo no se? and maybe a few other words for common objects, intertwined with my native tongue of English. Words and phrases I can’t even come up with under pressure.

Perhaps my recent discovery that I understood more Spanish than I originally thought gave me the confidence I didn’t deserve to volunteer to do this translation. I feel I have done a disservice to a language I don’t fully understand, and even if I did, translation is difficult on its own.

It was four verses in that I realized my translation was cheap and almost a caricature of my own culture, a culture that I already feel as though I am merely a bystander to, watching from afar. A spectator to something that I could be an active participant to, if I only knew the language better and lived the culture more. But, alas, I am but a visitor. I’m missing the nuances needed to do the work justice. And even if I felt like I was strong enough, there would still be some loss in the translation. Sadly, I am not equipped enough to recognize the loss, because I’m too concerned about finding a fitting word or phrase in the first place.

Words and phrases I can’t even come up with under pressure.

Another obstacle I didn’t take into consideration when I first started translating was the extent to which Spanish — as is the case with most, if not all, Romance languages — is gendered. (I only have limited knowledge of Spanish and French.) For instance, when Romeo describes Juliet as “the sun,” in Spanish the sun is masculine — el sol. I couldn’t change it to la sol, and if I kept it in its masculine form, he would essentially be describing Juliet with masculine adjectives. I’m curious to find a Spanish translation of Romeo and Juliet and see what they did in that case. Maybe it isn’t that big of a deal, but I’m not comfortable enough in Spanish to make that decision.

I tried to enlist the help of my mother, but even she, a native Spanish speaker, did not feel confident enough to do the translation justice. How had I, a weak Spanish speaker, arrogantly think I could translate a passage into Spanglish, let alone translate a Shakespeare passage into Spanglish?

Overall this has been a humbling experience. I have much more to learn about my mother’s native tongue. It’s also reinforced my feelings of being an outsider to my culture. I have a lot of examining of myself to do. It’s not all a loss because, I think, this experience gave me a chance to see where I actually fall in my understanding of Spanish, and, of course, it reinforced the idea that there is much lost in translation, not only in language but also in culture as a whole.