AISTE GUOBYTE

It’s Sunday, June 6th, 1841: the eve of Census Night in Killashandra, County Cavan in Ireland. Patt Leddie (60 – farmer – head of the family – can read and write English) is at the table next to a pirouetting flame, with a pair of teabags in the pot and the sound of the rain hitting the one-story roof in the background. As head of the family, Patt has been instructed to fill out a form detailing the inhabitants of the house on this day in 1841. This includes his wife Susan, a 60-year-old housewife who can read English but not write, two daughters whose occupations are outlined as ‘spinsters,’ a 15-year-old son who is employed as a labourer, a young cousin, and a deceased father who passed from ‘decay’ six years prior. Fifty years later and the census would ask for the religion of each person, whether they speak Irish, and whether anyone in the family is considered to be “deaf, dumb, blind or a lunatic.” Another hundred years on and we would know how Patt traveled to work, precisely where he has lived outside of Ireland, and how he would rate his health.

The census in present-day Ireland doesn’t quite set the same scene. You receive the census weeks in advance, likely wait until close to the deadline to complete it, and the collectors anxiously race around subdivisions, farmlands, and hard-to-access apartment complexes desperately trying to collect the forms within their required timeframes. The census holds a unique significance in Ireland given the country’s history: the first census in Ireland was during colonial rule, and thus is part of the impact of British colonialism on the island. Sure, the census may seem relatively innocuous — we can use the figures to show that there are more sheep in Ireland than people. However, it is no voluntary undertaking. Every person in Irish territory on Census Night is legally required to complete the census, and the practice of quantifying and aggregating the population — sometimes referred to as political arithmetic — is fraught with philosophical and political issues.

Although the census initially began as a thorough headcount of the population, it has become an increasingly sophisticated instrument: a full-fledged social survey expanding the reach of government.

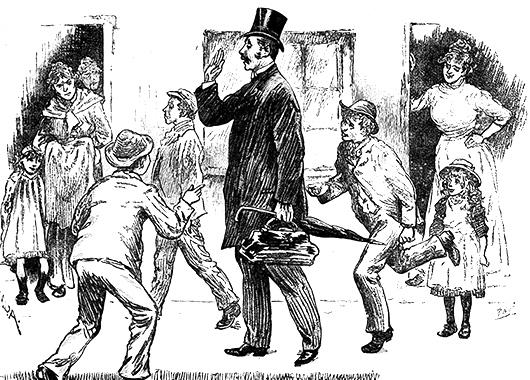

The Census Man | Source: © National Archives

Early enumeration in Ireland was a tool in the late stages of 800 years of British colonial rule in Ireland, which began in the 12th-century. Within Britain, enumeration began with government official and statistician John Rickman’s development of a British national census in 1798. Rickman did not shy away from overtly justifying the census as a form of government authority and population control, and went on to write that “the intimate knowledge of any country must form the rational basis of legislation and diplomacy.” Furthermore, he stated that “an industrious population is the basic power and resource of any nation, and therefore its size needs to be known.” The intentions of the British government at this time was to promote its supposed interest in the public good, assess the makeup of the population for military purposes, and stimulate the economy in ways that suited the interests of the governing elite. Some have suggested that the collection of statistical information in Ireland by the British administration was a kind of “Victorian bureaucratic obsession” that aimed to increase control over the island. It is no surprise then, as Michel Foucault argues in Birth of Biopolitics, that modern-day Western governments evolved alongside the growth in administrative and statistical thought.

https://www.instagram.com/p/tF8e1SGLB9

Source: fizzybellaflagstaff/Instagram

In Ireland, the first successful census of the population was carried out in 1821. Individuals reported their age, occupation, and relationship to the head of the household. They were also asked about the nature of their dwelling and the materials with which their house was built. The census was repeated at ten-year intervals until the War of Independence freed the Irish State from British control and the outbreak of an Irish Civil War halted enumeration in 1921. Finally, under the Irish Free State, the Statistics Act of 1926 outlined how the newly formed Irish government was to carry out the census and the obligations of the country’s inhabitants. Over the next 70 years, the amount of information collected by the Central Statistics Office has gradually increased. In present-day Ireland, the census is carried out every five years, with the most recent one being completed in April 2016. Although the census initially began as a thorough headcount of the population, it has become an increasingly sophisticated instrument: a full-fledged social survey expanding the reach of government.

The collection of social data is said to play a major role in modern governments’ attempts at regulating its citizens; sociologist Nikolas Rose aptly highlighted that national statistics and thus governments create lifestyles and identities which are then perpetuated by the population. The census is, however, faced with the critique that it fails to accurately represent a nation’s residents. It hinges on the expectations that respondents fit into predetermined categories; that they are interpreting questions as intended and answering truthfully; that the population is more or less fixed, and so on. Critics have specifically pointed to limited response options and the infeasibility of reflecting a complex and increasingly diverse population. These critiques rise in volume as we see the effects of globalization and the free movement of labour across European nations on population demographics. Even those who are relatively uncritical of these epistemological assumptions upon which the census is based on acknowledge its inability to reach hidden populations (e.g. those experiencing homelessness).

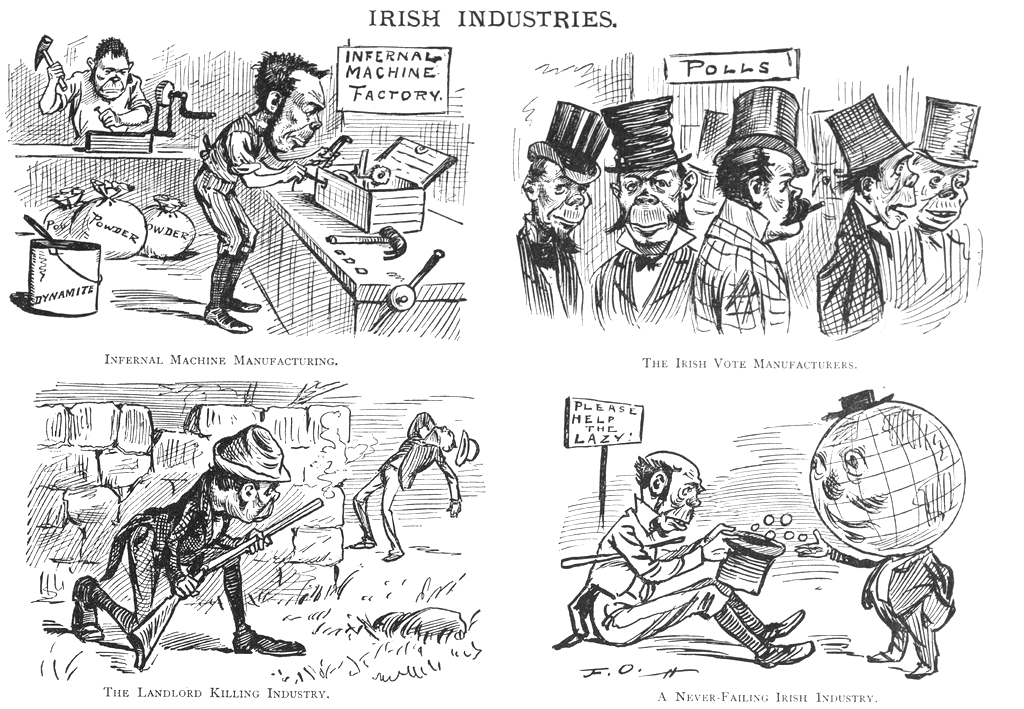

Attempts to quantify ethnicity have especially exposed these limitations — think about the creation of the “Hispanic” category in the U.S. census; confusion and ambiguity regarding race and ethnicity in the U.K., and so forth. Should racial categories be mutually exclusive? Why are ethnicity and race counted separately? This difficulty in representing a population is not just problematic in how the data is collected, but also how this information is reported. For example, given the low population numbers of residents of certain ethnic backgrounds in Ireland, particularly those that are captured broadly (e.g., “other”, “other Asian”), it is difficult to assess marginalization and levels of social disadvantage these minority groups face. In this way, the census fails to capture the needs of certain groups. Ambiguity, exclusion, and elusive categories of ethnicity also contribute to what can be described as ‘statistical invisibility.’ This is exemplified by vague categories that fail to represent minority and groups of mixed-ethnicity. An early example of evolving categories is the case of Irish immigrants in America. It is well documented that, while the Irish were initially racially oppressed, their eventual support of the continuation of slavery earned them the essence of whiteness in the America (for more on this, read How the Irish Became White). In fact, even in the U.K., the Irish were considered a “disadvantaged, racialized minority for over a century” during British colonialism.

1881 Cartoon from Puck magazine Depicting Irish Discrimination | Source: Irish Memory/Blogspot

Another site of contention is religiosity. There are two statistics of interest here: according to the census, 91.2% of people in Ireland consider themselves as being “of a religion” and 78.3% of the Irish public consider themselves Roman Catholic. These statistics have been used to give legitimacy to the prominence of the Catholic Church in Ireland and the need for religious education in schools. However, there has been a major rise since the census of 2011 of those who did not state a religion or indicated that they have ‘no religion,’ with an increase of over 70 percent in each category. More representative studies have found that mass attendance has declined to 30-35% in recent years and that only 54% said that religion was important in their daily life. Results of the marriage equality referendum in 2015 — a nationwide vote to amend the Irish constitution and legalize same-sex marriage — showed that a large majority (62%) voted to support same-sex marriage, rejecting traditional Catholic values. No less frustrating is that news outlets have used the census to suggest that 91.2% of people in Ireland “practice a religion,” despite the word “practice” not appearing in the census survey.

Nevertheless, this is not to imply that Catholicism and religion have completely lost its political powers as a result of its decline. Indeed, various Catholic churches still own and support the majority of primary schools in Ireland, and it was only this year that publicly funded schools decided to drop formal religious instruction in preparation for confirmation or communion during the school day. The influence of the Church is also very visible when considering within the 2018 abortion referendum where the Irish public will be asked to vote to repeal and replace the Eighth Amendment, which prevents women from having an abortion unless the woman’s life is at risk. Perhaps most exemplary of this influence was the case of Savita Halappanavar who, despite being at a risk of death, was told by a midwife that they could not terminate her pregnancy because Ireland was still a “Catholic country.” As the ongoing debate intensifies, both historical and continued attempts of controlling women’s bodies are characteristic of how Catholicism has been deeply embedded in Irish culture.

National statistics and thus governments create lifestyles and identities which are then perpetuated by the population.

It is not far-fetched to suggest that Catholicism in Ireland has become increasingly more cultural given the rate at which religiosity appears to be plummeting. Evidence of cultural religiosity is clear all across the country considering how numerous churches and crosses are, with continued religious rituals in birth, marriage, and death — and surely, there is nothing more Irish than quoting Father Ted, a popular Irish sitcom about three Catholic priests, in everyday conversation. In light of this difference between cultural and traditional Catholicism, and to lessen the influence of the Church, there has been a move within the country encouraging individuals not to write “Catholic” on the census.

Source: shremmm/Instagram

The census plays a profound role in the production and reproduction of state power, both historically and presently. However, as with many forms of governance, it has also been used as an avenue for resistance by social movements and political activists. In the early 20th-century, Violet Tillard and the Women’s Freedom League resisted and evaded the 1911 census as they felt they were not treated as full citizens in Great Britain. The women encouraged each other to spoil their census forms or evade collection by ‘going to a party.’ What we can take away, and as what sociologist Rebecca Jean Emigh and others argue, is that “censuses function best when there is intense interaction between the state and society, not when censuses are insulated in highly autonomous bureaucracies.” Movements to resist, modify, and counter the assumptions of the census are examples of such interaction between the state and society. They represent a shift from passive to active participation by citizens of a healthy democracy.