A few months ago I wandered into an exhibition of Sally Mann‘s photography. I have to admit that I had no idea who she was, but I was enchanted by the arresting black and white photographs of wild Virginia fields and forests. It quickly became clear, however, that this was not going to be an idyllic walk through the woods. The gallery displayed photos of her naked children, the black woman who raised Mann (who is white) and her siblings, decaying Civil War-era monuments, the backs and legs of anonymous black men. I could see why the gallery notes kept referring to her as controversial. The photos were so full of emotion: Mann’s anger towards her homeland, her bewilderment at her family’s complicity in the perpetuation of historic oppression, and her fierce love for her children and her home state of Virginia. But none took precedence; all emotions burned at the same temperature.

I was reminded of this artist and her work when I read Caleb Lewis’ piece about the American South. Life Below the Mason-Dixon takes a square look at a fraught place that so many Americans call home, meditating on the stereotypes and realities that characterize this land. I love the way he shares some of the South’s worst memories and mistakes, and then gently turns the flashlight on the rest of the United States — who are we to think we’re exempt from these kinds of sins? He suggests healing a culture of silence by way of exposure: we can only chip away at big problems when we talk about our own little ones, the ones that haunt us like ghosts in Southern mansions. It’s a piece that reminds us, as we head into an election year, to choose conversation over silence, critique over blind faith. Love of a place does not have to be, nor should it be, unconditional, and the conditions that this piece sets are thoughtful. It is our job to take care of each other and live kindly. “Maybe the South can serve as a cautionary tale, as a reminder to love others and not remove their humanity for your own self-interest.”

CALEB LEWIS

Carolina In My Mind

If home is tied to place, then I can’t really say I’ve ever had one. I’ve never lived anywhere long enough that’s transcended to that status. See, I was born in Decatur, Georgia, a place I don’t remember because my family moved to South Carolina around the time I was two. And much of the time since was spent moving around the state, following my father’s vocation as a Methodist minister. It wasn’t ’til I went to college in D.C. that I lived anywhere longer than three years. Throughout my childhood, though, I got to know the different parts of South Carolina. I’ve lived in a home surrounded by fields and forest. On Main Street in a one stoplight town. In the boonies on the side of a rural highway. And in the downtown of a Southern city. I saw what the South had to offer, and how its landscape was integral to its identity, from the swamps to the mountains. Its people have been shaped by this land over generations, by the red clay exposed like gashes underneath, by the air so humid you can swim in it, by the hurricanes so destructive they’re discussed in solemn tones decades later. It’s made them a people who are both stubborn and kind. And it’s created all of the faults and graces we recognize as uniquely Southern today.

When I was growing up, I tried to reject these Southern ways, which is probably normal for kids my age raised in a liberal family. I avoided saying “y’all” and “ain’t,” I despised camo, and I loathed country music. Don’t even get me started on my American football heresy. All I knew was that I was different from the culture around me, and so I created identity in performing anti-Southernness. But when I reached D.C. I suddenly had other cultural landmarks to contrast myself with. I learned that I had taken grits and sweet tea for granted. I was shocked to find that my language reflected the culture of my raising more than I had believed in both word choice and accent. And in this contrast I began to feel something I had never felt before: homesick. I was homesick for a place I grew up holding in contempt. I had seen everything wrong with the region first hand: the bigotry, the prideful ignorance, and the hatred. And yet, I discovered I loved the place, too. Suddenly the things I loved about it came to light. My family, the beautiful country, and, yes, the food. I realized that despite my best efforts, I was Southern. And so I began to struggle, “How is this possible to both love and hate your home? How do you make peace with a place so terrible and great?” My identity, that most precious of human objects, was thrown into flux. I began looking for answers in the world around me. What exactly was I rebelling against?

Meet Joe Sixpack

Think of a Southern man. What does he look like? I’ll bet the image that comes to mind is some guy in camo with a loosely buttoned flannel wearing boot-cut jeans and the boots to match. It’s not entirely inaccurate. And you come by it honestly. You’ll find the extreme in TV shows like Duck Dynasty, but the typical Southern man can be seen in just about any bit of entertainment set in the South (or just passing through): Justified, Hart of Dixie, True Blood, The Walking Dead, and Friday Night Lights, to name a few. And in reality, tons of white men in the South dress exactly like this. In a way, it’s the uniform we’ve sold ourselves. Southern culture presents an image to Southerners of what they’re supposed to look like, and Southerners eat it up. Because Southern Man embodies the ideals of the South: a white man who dresses not for fashion but for work, who upholds traditional masculine, conservative values, who works hard, parties a little less hard, and finds a way to a pew come Sunday morning, and we hear it all the time in mainstream country music. I would call out specific country songs, but it’s literally every country song, and it’s hard to tell which came first: the desire for Southern white men to present themselves this way or the songs telling them to. But either way, it works. When I want to feel a little closer to home, when I want to feel less alone, when I want to feel part of something larger than myself, I listen and sing along. It taps into the desire to feel understood, non-negligible, and it’s a tempting narrative — but not always an honest one. How many of these men really need their trucks or their boots to work or do anything productive? How many actually go hunting? I can tell you: very few. But the camo sure looks good.

The South is a reminder of how things are supposed to be. The simple, rustic ideal. But underneath the surface, “how things are supposed to be” actually means a world dominated by white men.

Duck Dynasty: Catch Phrases (A&E) | Source: © A&E/YouTube

But now think about the landscape of the South. The image that usually comes to mind is rural, whether it’s fields, forests, mountain hollers, or swamps. In short, there’s a lot of land and not a lot of houses. This image is completely true and has been for much of the region for eras. It’s that vast emptiness that I believe to be the source of a lot of Southern values and images. For instance, our Southern Man is absolutely going to have a truck and wear boots; there’s less paved roads and a lot more grime to walk through in the South. Along with the large tracts of land comes more reason and opportunity to be outdoors — whether for work or recreation — which requires a preference for utility in your sartorial choices. As far as the camo… well, I can’t really excuse that since you shouldn’t be wearing your hunting gear out and about anyway. It smells too much, otherwise. But I can at least say that it stands to reason you’ll find more hunters in a region where there’s more hunting to be done. I guess you could go hunting for deer in San Francisco. But I doubt it’d yield much game.

I Know You Are, But What Am I

Southerners like to tell stories. And some Southerners tell themselves a story that glorifies the Old South, or the current one even, without the taint of racism so they can feel proud of their community — or heritage, as they say. Some even downplay it or defend it as a way of life. Outside of the South, this image is seen differently. Southerners are seen as religious bigots, ranging from simple and dumb to downright dangerous. And though it’s a stereotype, the image bears truth. The South has some of the highest rates of violent crime and some of the lowest high-school graduation rates. Southern states also tend to have a higher concentration of hate groups. The popularity of this image outside of the South stems from a couple of sources. First, the rest of America is afraid of the South. They’re afraid because they don’t understand its people. And they’re afraid of the image that’s been perpetuated for generations. But I think the main reason Southerners are presented this way is for contrast. The South serves as the scapegoat and sin-eater for the rest of the country. It’s Southerners who think backwards — not our neighbors, and not ourselves. It’s a coping mechanism. A form of denial where the rest of the nation gets to be the good guys.

A Timeless Piece from Behind the Scene of Andy Griffith Show | Source: Bill Claussen/YouTube

However, sometimes the outside image of the South takes a much gentler form. Think The Andy Griffith Show, where time moves slow and life is simple. In this setting, the South becomes the pastoral ideal, something to aspire to when life gets too hectic or overwhelming in the big city. The South is a reminder of how things are supposed to be. The simple, rustic ideal. But underneath the surface, “how things are supposed to be” actually means a world dominated by white men.

Say What You Mean

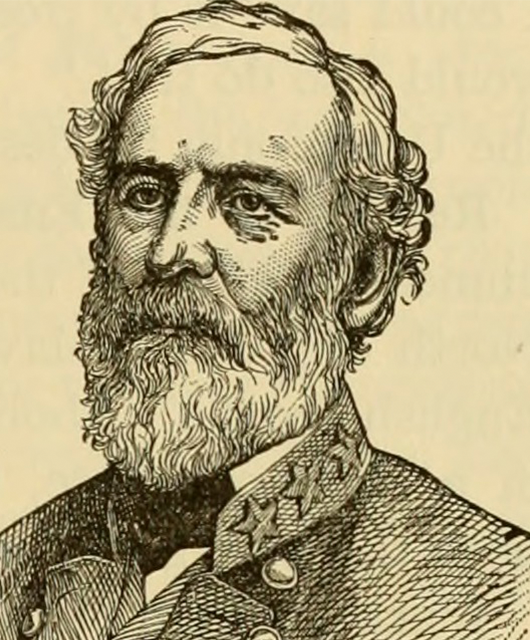

Robert E. Lee | Source: Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr

And here is where I really need to call myself out. So far, when I’ve talked about Southerners, I’ve referred more often than not to white Southerners, implicitly and explicitly, and, even then, usually white Southern men, partly because of the image portrayed in media. For some reason it seems, Southerners are always white men in TV and film, and I wonder why. But part of it is also my experience. I am a straight, white, cisgender man. That’s the experience I know, so it’s the one I feel most comfortable talking to. However, that’s exactly the problem when it comes to creating images of the South. Sure, I also happen to be a progressive, Socialist (or at least I try to be), and that, too, is outside of the perceived norm. But at the end of the day I am aware that as a white Southern man I am susceptible to all the same mistakes and flawed thinking that comes with that. I’ve been socialized within a community that grew out of a soil of hatred, and I worry. I worry that I can’t do better. That I’m doomed to repeat cycles and behavior of white supremacy because it’s ingrained in me. For example, in the South, we speak indirectly. This means, when asked where we want to eat, instead of saying “I want to to go to Taco Bell,” we’ll say, “Well, I think it might be kinda nice if we go to Taco Bell, but I’m happy to go somewhere else if you’d like.” We talk around what we mean. And even though I haven’t lived in the South for eight years now, I just can’t speak differently; it’s part of who I am. This way of talking is part of the “polite” culture Southerners are known for. While food is a trivial issue, these methods of communicating bleed into important ones, like race. We’re trained not to face and discuss issues head on, and instead, we learn to avoid rocking the boat. To keep your head down. And to keep silent. But silence is complicity, and politeness and silence are values and tools of the white supremacist system that keep it intact. You can’t fix racism if you never acknowledge and address it.

While there’s no complete explanation for the rise of politeness in the South, we can still say that the land helped to mould its people. In 1996, a theory was presented about the culture of honor in the South. I’m not a scientist, but here’s the gist: many of the early European settlers in the South were Scots-Irish herders, who brought with them a certain sense of responding aggressively towards infractions of the social code. This system of aggressive response arose from living in a region of the British Isles with a lot of land and very little government policing. The inhabitants had to police the land themselves in order to protect themselves and their property. While the South relied more on farming than herding, it still had large areas of land with little policing, and so the culture of honor spread and grew throughout the South. Some point to this honor culture as an explanation for the prevalence of violent crimes in the South.

Lectures in History Preview: The Idea of Honor in the Antebellum South | Source: © C-SPAN/YouTube

White Southern men have been taught to respond aggressively to perceived insults and threats to themselves, their property, and community. This influences the “stand-up and fight back” aspects found in Southern culture, especially in country music. In turn, this produces the polite, indirect, and, frankly, passive aggressive culture of the South, where violence can break out over any infraction, so it behooves you to be careful about your behavior and speech. Issues can’t be confronted directly for fear of retaliation, so they must be approached sideways or roundways, couched in respectful language and behavior so as to not offend anyone. I also believe this culture partly explains how traditional and conservative the South is. Southerners fiercely protect their ways of living — their identities. Any mere questioning of those becomes an insult that must be rectified. When questions aren’t allowed, change is hard to come by, causing the region to lag behind the rest of the country.

I don’t want to be a part of the culture of silence. So, I’m going to do what I can to present other narratives, include other stories, or at least point to places where you can find them. I may make mistakes. But I’d rather face it directly and learn how I’m wrong than be silent.

Our Southern Man isn’t the only person in the Southland.

Welcome to the Dirty South

Amongst the groupings of traditional and stereotypical Southern imagery that dominate the landscape, we can find other Souths. There’s more going on in the nooks and crannies of the region — in the hollows, in the valleys, along the coast, and in the swamps — and there’s plenty of space for other ways of being. Other forms of being Southern. These are the Souths that statistics show are growing and changing. Southern states tend to be above the national average in diversity of race and ethnicity as percentage of population. Our region holds the majority of the Black population of the United States, a whopping 55 percent when compared to the next highest concentration of 18 percent in the Midwest. And this lion’s share seems to be growing with what some are calling a New Great Migration or a Reverse Great Migration back to the South. This trend of Black Americans moving South has helped reshape the landscape, pushing some locations, especially the suburbs of metropolitan areas, towards progressive politics and Democratic nominees. This specific trend of migration also sits within a larger trend of growth in the South, with many people of all types moving to its cities and suburbs to build lives. Our Southern Man isn’t the only person in the Southland.

By Every Means Necessary: Southern Progressives Are Shaking Up Politics | Source: © The Laura Flanders Show/YouTube

One of the leading voices in the movement to uncover different Souths is an online magazine based out of Atlanta, Georgia called The Bitter Southerner, who declared in their first article and beginning mission statement:

If you are a person who buys the states’ rights argument… or you fly the rebel flag in your front yard… or you still think women look really nice in hoop skirts, we politely suggest you find other amusements on the web. The Bitter Southerner is not for you. The Bitter Southerner is for the rest of us. It is about the South that the rest of us know: the one we live in today and the one we hope to create in the future.

A sentiment which they would reinforce a year later in their first membership drive with this quote from Southern rock musician Lee Bains III:

“It doesn’t matter where your parents were born or what religious tradition you follow or what type of person you find attractive; if you say you’re a Southerner, then you’re a fucking Southerner, and we need to hear about it.”

The Bitter Southerner seeks to help bring voice to many left voiceless in the South, to shine a light on issues that normally get swept under the rug, or sometimes just to tell brilliant stories that otherwise go overlooked, either because of “politeness” or just because it doesn’t fit the mainstream idea of the South. They’ve published stories about mariachi bands, peculiar strip clubs, the LGBTQ+ community in Atlanta, and meditations on Southern identity. And that’s just from their first three months of existence in 2013.

Source: © The Bitter Southerner/Instagram

But writers from The Bitter Southerner aren’t the only storytellers and artists looking to change the narrative around the South. Donald Glover’s Atlanta provides a darkly comic perspective of the region that pulls from the spiritual and otherworldly tradition of Southern Gothic literature. Atlanta is situated within a wave of shows like Queen Sugar, Rectify, and Preacher (I would also highly recommend the comic series Southern Bastards by Jason Aaron and Jason Latour) that seek to complicate the picture either by giving a platform for people who don’t normally get one or to turn traditional views on their head. Either way, they end up exploring the South with more nuance and robustness than just about any show before.

But the difficulty for a new, Southern perspective to gain recognition is nothing new. For one of the best examples, look no further than the 1995 Source Awards, celebrating the best of rap and hip-hop that year. There’s a lot of complexity when it comes to the events of that night, too much to go into here. But for our purpose, here are the basics: the East Coast-West Coast rivalry was reaching a fever pitch; it was the same night that Suge Knight “invited” artists to “come to Death Row!” to escape P Diddy, who fired back with, “I live in the East, and I’m gonna die in the East.” The only sound the audience wanted to hear that night was East or West. So when the Atlanta based group OutKast approached the stage after winning Best New Group, they were showered with boos. Although Southern rappers had been releasing some of the best and most adventurous work in the nation for years, the region had been ignored as distinct in its own right in favor of the East-West divide. And as Big Boi and André 3000 faced being drowned out and ignored yet again on one of rap’s biggest nights, André shouted out what would become a rallying cry for Southern rappers to this day: “The South got somethin’ to say.”

Outkast winning Best New Rap Group at the Source Awards 1995 | Source: TheMaxTrailers/YouTube

To Strive, To Seek, To Find, and Not to Yield

The South is fighting over its future. This fight is happening because every Southerner is struggling with their identity. It’s a struggle between the best in us and the worst, and it’s the same struggle I’ve faced since I was young, though I wasn’t aware until college. Earlier, I asked how someone makes peace with that conflict of love and hate for the South, but the reality is you don’t. The struggle is the nature of the beast. The closest you can come is recognizing that both the bad and good are a part of the unique individual you’ve become. But there’s still no solace in that. And so I struggle still. I’ve tried to embrace my Southernness and perform it more. I’ve actively tried to reintegrate the “y’alls” and twangs into my speech. I wear more Carhartt and Atlanta baseball caps. And I cook myself grits and look for good barbecue. Yet, I try to do so responsibly, with a knowledge and respect of where they come from. The reason we have so many riches — including barbecue, the banjo, okra, and so much more — is because of the ingenuity and bravery of enslaved peoples in the South.

Acknowledging the troubled history of our treasures isn’t just important, it’s necessary. This means holding that history within ourselves so that we don’t forget, so that whenever we pull from our traditions we do so with thanks and reverence. But it also means sharing that history. For example, when I play the banjo, I’ll make a point to discuss the instrument’s path from a stringed gourd instrument with roots in West Africa, to its popular use in minstrel shows, and to its growth into multiple genres of popular music today. History must be respected and owned. But sometimes history weighs too much. Though the Rebel Flag has become a symbol of Southern culture, I refuse to identify with it in any way. From its start as one of the many military flags of the Confederate States to its resurgence as a symbol for segregationists during the Civil Rights Era to its subsequent prevalence among hate groups today, its history holds too much. To condone the flag is to condone its history. And so it must go. Sifting through traditions like this is the job of any responsible Southerner. And every Southerner will have their own answers.

[There’s] plenty of space for other ways of being. Other forms of being Southern. These are the Souths that statistics show are growing and changing.

South Carolina’s 1876 coat of arms | Source: Wikimedia Commons

For my part, I take responsibility for the aspects of Southern culture I perform to remind myself of where I come from and to understand it more, to stay neck deep in the struggle. But I also do it so those around me know too. Sometimes just so they know my story. Yet I also hope they recognize that people like me exist too, that there’s more possibilities for what being Southern means. That might be asking a lot of myself, verging on delusional, to struggle with the South both inside myself and out, hoping for some form of victory. But then again, I’m from South Carolina, and the motto of South Carolina is Dum spiro spero. While I breathe, I hope.

Silence

Now, I haven’t quite held true to my word on not remaining silent. In order to do that I have to directly tackle something I’ve been speaking around this entire time: the history of the South is the history of the abominable enslavement, oppression, and torture of millions of Black people for hundreds of years, the cause of which is both known and unknowable. Known in that we can point to the force of a profitable agricultural economy gaining advantage in exploiting free labor by denying the laborers their very own humanity. Unknowable in being left to wonder how any person can cause such barbaric harm to any single person, and then to multiply the inconceivable by millions. Everything about the South is inextricable from this history of the abhorrent. It weighs on every aspect of the culture. Every Southerner has to wrestle with it, regardless of how they identify. It haunts the air every Southerner breathes. And yet history can’t haunt the South. Because it’s still alive. It’s not even history. I don’t just mean that the Jim Crow laws were only struck down 50 years ago, which is no amount of time at all. I mean that the Charleston Church Massacre occurred in 2015. I mean that the Confederate Battle Flag is flown throughout the South to this day. I mean that the current governor of Virginia appeared in blackface in his medical school yearbook. In the words of Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

This. This is the gaping wound at the heart of the South, at the heart of any Southerner’s identity. For white Southerners, this means coming to terms with our place in that history and acknowledging that place is tied to atrocity. For Southerners of color, especially Black Southerners, I can’t truly say what they experience. That’s not for me to know. But I’m sure it’s even more complicated, more fraught to know the place they live, and maybe love, was built on the blood and sweat of their ancestors. To know that the systematic structures of today have their roots in that soil. That’s the depth of the evil that we struggle with. And each of us deals with that struggle differently. Some cope through denial, either by saying slavery and racism were never that bad. Or they just don’t think about it, denying that history any meaning in their lives. Others cope by rejecting the South and their Southern identity altogether, removing anything that might link them to its darkness.

The South is fighting over its future. This fight is happening because every Southerner is struggling with their identity.

But as for me? How do I cope? I don’t think I do. I feel stabs of conflict every time I claim links with the South. I always wonder if I should just let them go. Or if I should sit in humbled silence any time issues of race come up. Or if I should be among the first to step up and point out the wrongs perpetrated by white Southerners to this day. I always wonder. I always agonize. To be honest, I don’t have the language to make sense of this experience. I don’t. How do you come to terms with that? How do we name something so vast and deep? And yet we must. It’s exactly that lack of language that has allowed the cycle to continue. When we turn a blind eye to history, we turn a blind eye to what’s currently going on too. This means problems don’t get addressed. And you can’t fix a problem that you don’t address. As a result, the specter of slavery has lowered on the land. And there it will remain until we as a people grapple with it.

The Abyss Will Gaze Back into You

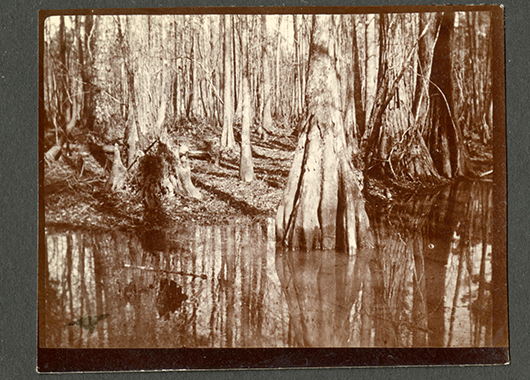

Cypress Swamp in South Carolina, 1898 | Source: Smithsonian Institution/Flickr

History haunts the South, and the land itself is haunting. The South is literally a dark place, without lights from cities and towns polluting the night sky or lighting the way for travelers down country roads. You can’t see what’s beyond the tree line or down the road or among the tombstones. It’s a scary feeling being surrounded with the unknown. I think that’s part of the reason there’s a long folk tradition of Southern ghost stories, a tradition that invaded the literature of the country through Southern Gothic. Moreover, it can feel like you’re at the mercy of something greater when you have a sense of connection to the land, a land you rely upon but have no control over. And if you can’t control it, then something else must. It’s that connectedness to the land plus the greatness of the unknown that causes the Southerner to check her shoulder at night, or paint her porch Haint Blue, or drive a little faster down that back road. Just about every Southerner I know has either lived in a haunted house or knows someone who has (according to my mother I’ve lived in at least two such houses). But I also think the prevalence of ghosts comes from what’s happened on the land. When the wound isn’t discussed, isn’t dealt with directly, then it has to find expression somewhere else. It’s hard to imagine such things occurring for as long as they did and into the present without some sort of cosmic force coming down to enact retribution. And so, much of the land feels tainted, if not cursed. The weight of the history becomes a fear of it. Of course there are restless spirits wandering the Southland. Who could rest with the nightmarish history of the land pressing on their soul?

It’s only a short jump from the spiritual and otherworldly to the religious. Although I doubt she meant it exactly this way, Flannery O’Connor once wrote, “I think it is safe to say that while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted.” Religion in the South has served much in the same way that ghost stories have: explanations of the uncontrolled events in our lives. Good times occur because God has blessed you or is rewarding you for your piety, while bad times happen because God is testing you or punishing you for your sinfulness. Either way, the unknown gets explained in the eternal. And even in church, there’s a struggle between the grace of God’s forgiveness versus the fire and brimstone of His punishment. Maybe this too is part of our struggle with our history. Can we ever find forgiveness or are we doomed? For many, the answer must be given up to God.

Why should you read Flannery O’Connor? – Iseult Gillespie | Source: © TED-Ed/YouTube

Life is Very Long

So what am I trying to do here? I’m not trying to defend the South; the South doesn’t deserve that. Nor am I trying to attack it, though perhaps that would be the right course of action. In the end, I’m wrestling with it, just like when I started years ago. I’m exploring the South, and in that exploration maybe I can come to an understanding or some explanation of the whys and the hows of it all. Maybe I can learn what to do with my gnarled inheritance. I look for the long view: the land itself has shaped the people, a people who are beautifully varied. A people with feet in the past but eyes towards the future. All the while, the image persists of the terrible South, the South to be feared and mocked, the South clothed in sin. In truth, I’ve begun to think that maybe we shouldn’t resist that image. It could be that it’s a part of the penance required of the South as recompense for its atrocities. Maybe the South can serve as a cautionary tale, as a reminder to love others and not remove their humanity for your own self-interest. Maybe that’s enough. Maybe being the sin-eater of the nation is exactly what the South deserves. Maybe it’s the only way the South becomes a place of love and progress. A place of healing where everyone can thrive. And then the cautionary tale might be shifted to a narrative of hope: look at what is possible. If it can happen there, maybe it can happen anywhere.

Acknowledging the troubled history of our treasures isn’t just important, it’s necessary. This means holding that history within ourselves so that we don’t forget, so that whenever we pull from our traditions we do so with thanks and reverence.

But I also can’t escape the reality of the short view: the South is all of the people and things that I love, all that I am attached to, the lens through which I experience life every day. And so it hurts me to see the South belittled and derided. I see so much to love, not only my family but also all of the people fighting the good fight or just trying to eke out an existence. So I can’t stand to see it all grouped together and ridiculed. It’s like hearing someone insult your mom. And I don’t know how to make sense of it. Because even if they’re not wrong, I still love it. So where does all of this leave me? I don’t know.

In all honesty, I feel the need to say something profound as my story comes to an end. As if to say I’ve gleaned some wisdom through my struggle, something I can share, something to show for the conflict. The truth is that I have nothing to say. No conclusions to make. There is no moral to this story But that’s reality. It’s only in works of fiction or in narratives plastered over factual events that a neat and meaningful finish can be achieved. The real world is beautifully messy and impossible to comprehend. We try to make sense of it. We try to give our lives meaning. But nothing can be wrapped up with a nice little bow. There’s no “happily ever after.” There’s only, “and they lived…”