MICHAEL DONNAY

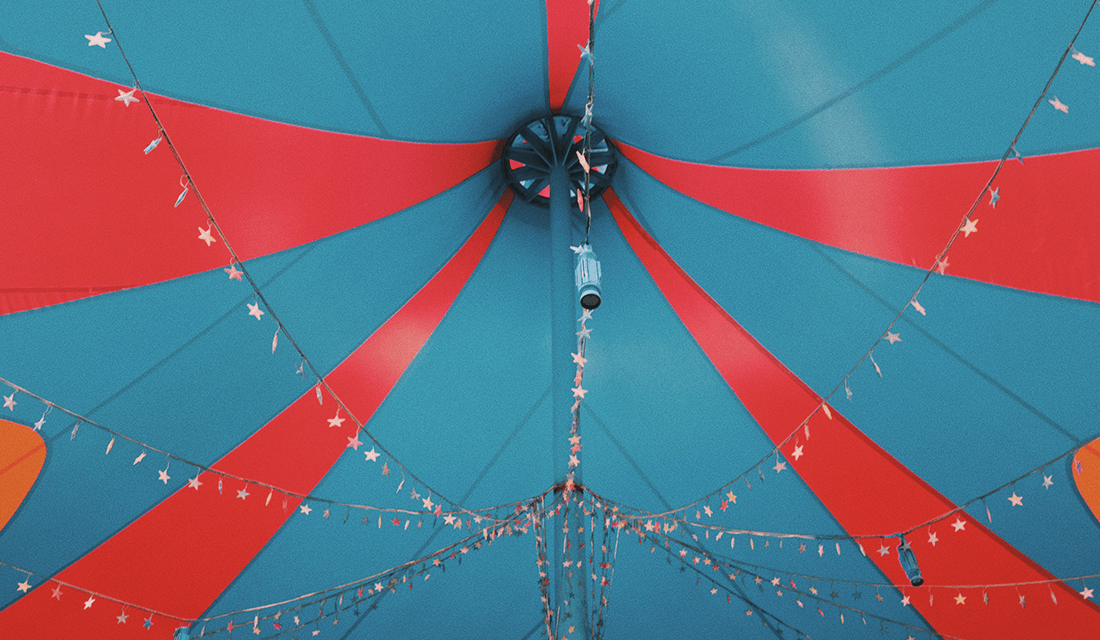

Airplanes had heralded its coming — passing low over the center of town last week to drop flyers announcing the circus’ impending arrival. The handbills began appearing a few days later, announcing the time of the performance in bold, colorful lettering. The space around the edges of the posters was filled with the most amazing animals imaginable — and some that were beyond imagining. Your friends began placing bets as to whether school would be canceled and you eagerly counted down the days until the mile-long train would pull into the station. When the morning finally comes — school having been blessedly canceled the night before — you all hurry down to the tracks to watch the workers begin unloading the massive train cars. The press of your neighbors trying to get a better view makes for a chaotic scene, but the circus continues working with crisp precision. Bundles of tent poles, cages filled with animals large and small, and troupes of brightly-clad performers spilling out in a carefully choreographed order. As morning turns into afternoon, the peaks of the big top rise above the fields on the outskirts of town.

Before that evening’s performance, there is a massive parade through the town. People come from miles around to see and your friends stake out a place on the roof of a nearby house to view everything as it comes by. The ringmaster leads the assembly, followed closely by a brass band playing rousing music. Behind them comes marching a riotous mass of color: acrobats in blue and red tights somersault through the street, carriages whose occupants’ bright orange fur stands out against the black of their cages, and massive gray beasts — bigger than four of the largest horses you’ve ever seen — decked out in gold and green. It seems like the poster has burst onto your front yard; an entire world strung along the road before you. Later in the tent, as the tigers growl and the gold beads on the elephants’ headdresses sparkle under the lights, you marvel at the spectacle of it all.

Lions, and Tigers, and… Corporate Spectacles

Scenes like this were common across the United States when the traveling, big top circus was at peak in the late 19th- and early 20th- centuries. Figures that would become staples of the popular imagination of the circus — the Ringling Brothers, P.T. Barnum, James Bailey — made their name and their fortunes during this period. At the same time, like so much else in the American economy, the circus was expanding into a corporate behemoth; the entertainment equivalent of the business monopolies of the Gilded Age. Large companies would travel with thousands of performers and staff, hundreds of animals, and tents capable of holding 10,000 spectators.

As circus impresarios pushed the scale of their enterprise to its limits, the original single circus ring expanded to three. This expansion and the economic decisions behind it prioritized spectacle — often including the exhibition and performance of animals — at the expense of more skills-based performances. Where horses and dogs once took center stage, circuses would add elephants, lions, tigers and other exotic animals to draw in larger and larger crowds. As the entertainment landscape shifted, this reliance on spectacle and animal performance would prove to be the circus’ ultimate undoing. But in the century before then, the spectacle of wild and exotic animals from around the world gave life to the entire experience.

Animals and Empire

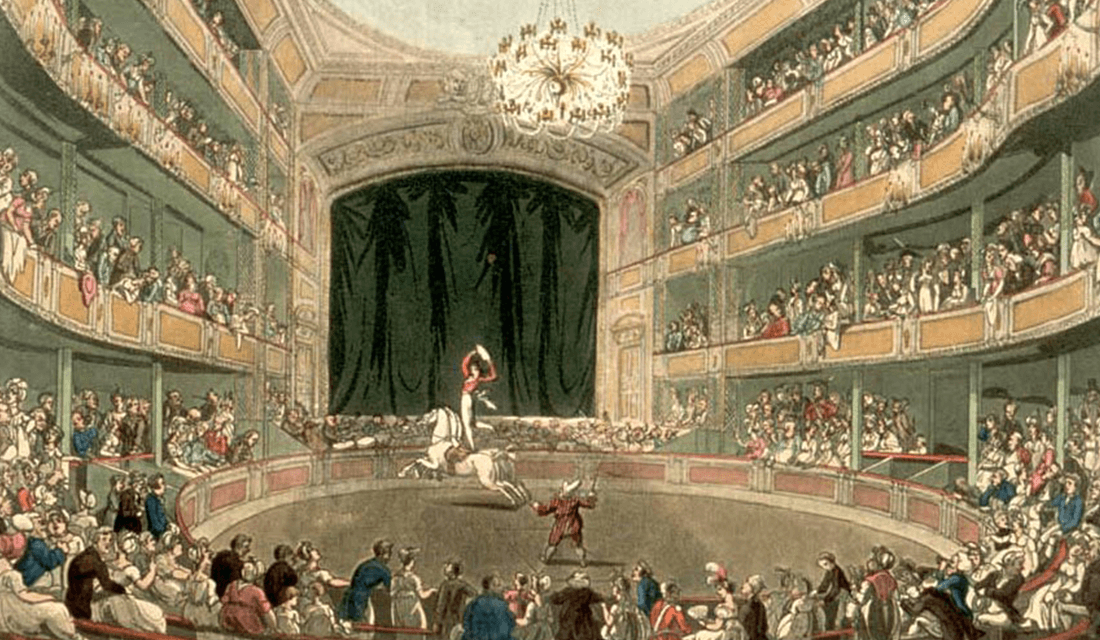

The first modern circus was created in the 1770’s by the former British soldier Philip Astley, who had recently returned from overseas service during the Seven Years War, and relied heavily on animal performance to draw in audiences. His performance was built around horseback riding and he began his career when people would stop to watch him perform tricks at his practice ground. He realized the commercial possibilities of this attention and soon charged a fee to watch his performance. He rode around in a circular ring, which allowed for larger audiences and provided additional stability for tricks, and when he added clowns and jugglers to his routine in the 1780’s, the circus in its modern form was born. Astley and other early circuses performed in purpose-built stadiums, and when circuses came to the early American republic, a series of circus venues quickly popped along the eastern seaboard. Like Astley’s circus, horses were the primary form of animal entertainment while human performers filled out the rest of the program.

Astley’s amphitheatre in London, c. 1808-1811 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

It was in America, however, where the circus transformed from a style of showcase centered around equestrian skills into the exotic spectacle of animals it became by the end of the century. In large part, the economic realities of a young nation impelled this development. In Europe and Asia, acrobats and other human performers travelled in their own companies and performed apart from animals. At the same time, traveling menageries that showcased animals from across European empires toured separately or were established in stand-alone venues (precursors to the modern zoo). In America, however, there was not enough financing, nor audiences large enough to sustain independent circuses and menageries. While some menageries did tour in the U.S. during the 1830’s, following the Civil War all but one had been folded into a circus organization. And what soon followed were audiences flocking to see these fantastical creatures, alongside unusual humans too, for the price of a single ticket.

Where horses and dogs once took center stage, circuses would add elephants, lions, tigers and other exotic animals to draw in larger and larger crowds.

Circuses and menageries built on American — and European — interest in the strange and unusual. With Europe (and soon America) wielding economic, military, and political control over much of the globe during this period, entertainment was one of the spaces where the benefits of empire for the metropole were on full display. Animals and performers became trinkets from far-off lands, symbols of imperial rule in often racially-coded displays. Circus performances allowed white western audiences to consume Eastern and African cultures in a space that also reinforced the superiority of Europe. And this relationship often extended to the animals as well -—their novelty balanced with the assured dominance of their white handlers. Coupled with the spectacle of the human performers, the excitement of these animals and their space in the social order made circuses a hugely attractive form of entertainment.

The Birth of the Big Top

It was in the period of massive economic expansion following the Civil War that the American circus reached its peak. By the turn of the 20th-century, over 100 major circuses regularly toured the U.S., and their tours were facilitated by the growing rail network connecting the country; some of the larger circuses relied on trains over a mile long to carry their equipment, performers, and animals. Circuses used this network to establish a national reach. Before the advent of commercial radio broadcasts, they were perhaps the only art form to truly do so. The rise of mass print media and advances in printing techniques also benefited the circus, as they allowed marketers to advertise performances to a wider audience; both message and medium became monikers of expanding wealth and power.

That audience was also expanding, as rising standards of living drove shifts in leisure culture. Industrialization picked up speed in the second half of the 19th-century and the middle class and urban working class expanded alongside growing cities throughout the country. As more workers transitioned to wage-based labor, they had disposable income that could be used on the type of public entertainment the circus provided. They, too, could access the world’s marvels brought right to their doorstep: wild animals from places they would otherwise only read about.

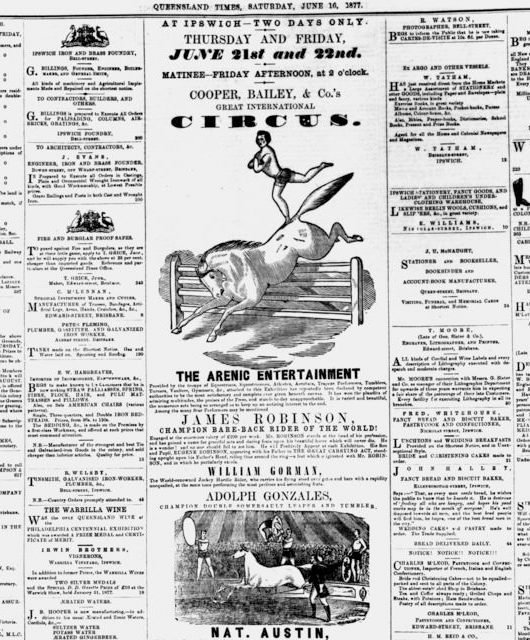

Advertisement for Cooper, Bailey & Co.’s Great International Circus at Ipswich, Queensland | Source: Wikimedia Commons

During the 1870’s, the powerhouses of the American circus world came into being, and as with many industries, which saw mergers or buy-outs, one such circus was born of the collaboration between two already prominent figures in the entertainment landscape. James Bailey and his partner James Cooper united to form the Great International Circus in 1872. Together, Bailey and Cooper pioneered many of the logistical techniques of the modern circus — including operating their own trains and developing the end-loading of circus equipment — and could move their circus up to 100 miles a day between tour stops. These innovations greatly increased efficiency and by the end of the decade allowed them to compete with another hallmark of circus history: P.T. Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth.

From their earliest days, circuses had relied on audiences’ fascination with the exotic — whether animals from other regions or people with particular skills or physical features — as a primary driver of ticket sales.

Barnum had begun his career by fraudulently promoting an enslaved African-American woman as George Washington’s former nurse in the 1830’s and had parlayed his success into the purchase of the American Museum in New York. The museum showcased both human and animal curiosities and attracted over 80 million visitors over its lifetime. Following its closing, Barnum partnered with W.C. Coup to produce a circus in Brooklyn in 1871. This circus featured a number of the attractions from the American Museum, from which developed what were called freak shows or side shows, unique elements of American circus. In 1881, Barnum and Bailey agreed to merge their two companies and formed P.T. Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth, And the Great London Circus, Sanger’s Royal British Menagerie and The Grand International Allied Shows United. This was quickly shortened to Barnum and Bailey’s Circus.

The Story Of The Greatest Circus & How It Came To Be | Source: © David Hoffman/YouTube

In many ways, Barnum and Bailey’s Circus set the standard for circus acts of the time. The logistical improvements pioneered by Bailey allowed them to move massive numbers of performers and huge pieces of equipment with relative ease, while Barnum’s skill as a promoter ensured large crowds wherever they went. When the shows were combined, they could no longer fit into a single ring (or even the two rings that both circuses had used occasionally from 1873 onward) and so the third ring was added. With three rings’ worth of performances occurring simultaneously, the more intimate elements of the show could no longer command much attention. As such, spectacle and scale became increasingly important. Performers attempted even more daring stunts, the circus built bigger sets, and Barnum and Bailey tried to acquire more impressive animals, doing just that in 1882 when they purchased Jumbo, an African bush elephant, from the London Zoo for £2,000. Weighing over 13,000 pounds and measuring over 10 feet tall, Jumbo proved enormously popular with American audiences, and Barnum recouped his investment in just one season.

Jumbo the Elephant | The Circus | Source: © AmericanExperiencePBS/YouTube

Coupled with the spectacle of the human performers, the excitement of these animals and their space in the social order made circuses a hugely attractive form of entertainment.

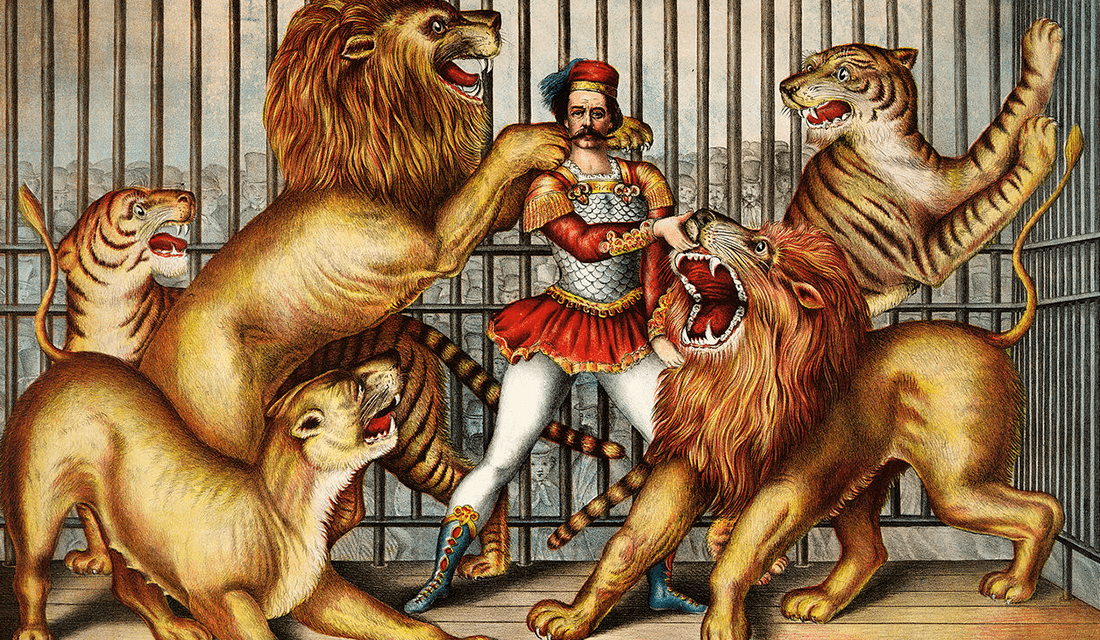

Large circuses, like Barnum and Bailey, built their shows around animal acts. Sometimes these acts revolved around a single, spectacular animal like Jumbo, but more often they relied on both scale and exoticism to wow their audiences. Where Astley had a single elephant at his circus in the 1770’s, Barnum’s show would sometimes have as many as 40 performing. Lions had been introduced in the 1830’s and were a regular feature at this point in the century. American trainers, in the tradition of the early pioneer Isaac A. Van Amburgh (supposedly the first man to put his head in a lion’s mouth and live), emphasized physical domination over the animals they worked with. This often meant beating animals into submission in the ring — the stereotypical image of the lion tamer with whip and chair. Emblematic of America’s confidence in the world and of white male dominance over nature, Van Amburgh’s style of performance remained the standard for American circuses through the middle of the 20th-century.

A lithograph of a lion tamer, c. 1873 | Source: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

While Barnum and Bailey’s expanded in the 1880’s and 1890’s, they faced competition from the other major American circus company: the Ringling Brothers. Originally founded in 1884 by five of the brothers — Albert, Otto, Alfred, Charles, and John — the company began expanding rapidly in 1888 when they purchased their own elephant. The brothers largely focused on the Midwest in their early years, but by 1900 they had adopted the train-based touring model and were competing directly with Barnum and Bailey. Like the corporate monopolists of the time, the Ringling Brothers fueled their expansion through acquisitions. They purchased many of their competitors, including Barnum and Bailey in 1907, and by the 1920’s they controlled 11 major circuses. In 1919, they merged their show with Barnum and Bailey’s performers, creating the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Combined Shows, which travelled with 1,100 people, 735 horses, and almost 1,000 wild animals.

From Tents and Trains to Arenas and Activists

Through the end of World War II, Ringling and its competitors remained a major force in American entertainment. They were even granted special rail privileges during the war because President Roosevelt recognized the importance of the circus to national morale. But technological changes were quickly presenting a major challenge for the circus. The advent of commercial radio and the rise of the movie industry in the preceding decades had started to draw audiences away from the circus by the 1950’s. Both media were easier and cheaper to distribute to a national audience, as the circus struggled to stay competitive while facing rising wages and fewer towns with enough space to pitch a big top tent. With the expansion of television broadcast, many in the industry predicted the end of the traveling circus, and in 1957, Ringling abandoned the use of its famous tent in favor of performing in arena venues.

From 1984: Ringling Bros. circus 100th anniversary | Source: © FOX 13 News – Tampa Bay/YouTube

Although the circus continued to do well through the 1980’s, there were signs that the style promoted by the early 20th-century companies was falling out of favor. Increasing economic pressure, including increased transportation costs and higher wages, as well as depressed ticket sales, drove some circuses to downsize. Others adopted stylistic elements from Broadway and film, in the process losing some of their distinctiveness. However, the major drive in the decline of the circus was a shift in American attitudes about the entertainment they consumed.

[…] entertainment was one of the spaces where the benefits of empire for the metropole were on full display.

From their earliest days, circuses had relied on audiences’ fascination with the exotic — whether animals from other regions or people with particular skills or physical features — as a primary driver of ticket sales. As America’s imperial reach had expanded, so too had the animal offerings of its circuses. It’s no coincidence that the circus’ popularity peaked in the same decades in the late 19th-century when the American political appetite for overseas acquisition did. However, just as the Vietnam era saw a decline in taste for such adventurism, Americans also found many types of animal performance less appealing as the century wore on. In large part, this shift was the result of the animal rights movement that grew out of the 1970’s.

As the circus expanded in the late 19th-century, importing huge numbers of wild animals, a few groups began expressing concerns over the practices involved in capturing and training them. Henry Bergh, who founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), had an ongoing (and occasionally tense) relationship with Barnum. Bergh even used Barnum’s circus as a test case for New York’s first anti-cruelty law in the 1870’s. However, serious and widespread opposition to the circus’ use of animals did not arise until the publication of philosopher Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation in 1975. Singer and another philosopher, Tom Regan, provided the intellectual underpinning for the modern animal rights movement. Both argued that animals should be given consideration in human decision making, either because they were capable of suffering — and that suffering should be minimized — or because they were capable of advanced cognition. With the founding of the Animal Legal Defense Fund in 1979 and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) in 1980, the circus faced its first concerted opposition on the grounds of animal welfare.

Animal welfare advocates argued that the conditions of circus life were inherently unsuitable for the animals involved, particularly the large wild animals like big cats and elephants that formed the core of the circus’ menagerie. Animals were regularly kept in cages for extended periods of time for travel and between performances, with many enclosures failing to meet the standards set by the industry itself. In one case, a lion died while being transported by train through Arizona when temperatures inside its car reached over 109º F. In another, a tiger was kept in its cage for almost 20 hours when a circus took a 5-hour trip to its next tour stop. Circus animals rarely get the space and socialization necessary to maintain their health, and animal rights groups argue that they are often denied proper medical care as well — claims the industry denies.

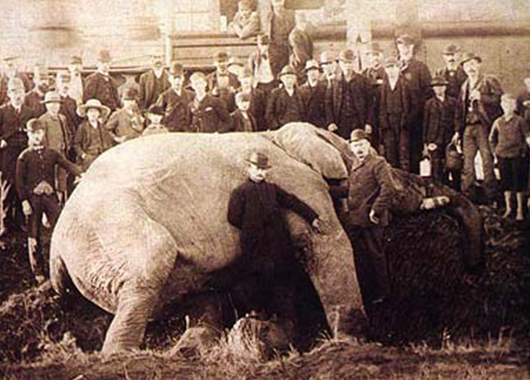

Jumbo after being hit by a locomotive in 1885 | Source: Wikipedia

The primary focus of activists’ work has been circus elephants. As the biggest symbol of the circus’ relationship with animals, both physically and in the minds of the public, the treatment of elephants has been a lighting rod for animal rights campaigns since the 1970’s. In addition to the challenges of housing and transporting such large animals ethically, the training and management of elephants has come under particular criticism. The use of the bullhook — a long pole with a metal hook on the end employed by elephant handlers — has drawn condemnation as causing undue harm to the animals. A number of cities and localities, as well as California and Rhode Island, have banned the use of the bullhook. The death of circus elephants through mistreatment or ill health has been a long running issue for the circus, going back to the death of Barnum and Bailey’s Jumbo in 1885 when the elephant was hit by a train. In more recent years, the escape and death of the elephant Tyke in 1994 brought additional attention to the continued mistreatment of the animals.

The Last Greatest Show

The mounting public pressure against circus elephants culminated in the decision by Feld Entertainment, which owned Ringling Bros., to end elephant performances in their circuses in 2016. The circus gave its last performance in May 2017. Although the management laid much of the blame at the feet of animal rights groups and the decision to stop using elephants, the circus had been struggling with low ticket sales for a decade. Competition from other forms of entertainment and broader societal shifts in attitudes towards animals had made traditional circus performance less appealing.

Why animal rights groups pushed Ringling Bros. to retire elephants | Source: © PBS NewsHour/YouTube

When the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus completed its final performance, it marked the end of an era in entertainment and the clearest sign yet in the shift of American attitudes toward animals. Once the center of an entertainment empire, all of Ringling’s elephants have retired to a conservation center in Florida, where they are cared for by scientists. And while they no longer perform for audiences, they now perform a new role: research subjects. Elephants are a species that shows an unusually low rate of cancer, and scientists are working with Ringling’s former animals to see if there are lessons for human cancer treatment that they can learn.

For all that has changed in the last century of animal performance in the circus, one thing remains constant even today: our relationship with animals continues to be a way of virtue-signaling. During the height of America’s imperial project, those virtues included white masculine dominance over the natural world, the superiority of Western culture over Eastern, and the celebration of the exotic. Americans — for the most part — no longer see these as laudable ideas. Thus the circus and circus animals, as the embodiment of many of these older values, have fallen out of favor. In their place we see animals at conservation parks or on shows like Planet Earth — spaces that let people signal contemporary values like working in concert with the natural world, privileging the knowledge of indigenous peoples, and celebrating ecological diversity. Through it all, animals serve as a lens to see the world — and our place in it.