ITUA UDUEBO

The employment of language in the service of inequality is a practice that we’ve engaged in since the earliest civilizations. Systems of hierarchy require effective socialization, and individual acts of derogatory speech is one of the most effective methods of creating social reality. Often this kind of speech uses language equating a person’s characteristics with those of animals, in order to dehumanize them. Associating humans, fellow members of the perceived apex species, with animals in a derogatory fashion actively diminishes their status as equals. Within the Western understanding of the human-animal paradigm, a group of people can be reduced to some animalistic trait then they can be reduced to, something easier to oppress and vilify. If you think of the people you commit violence against as equal to the livestock you feed on or the pests you exterminate, then such horrific thoughts and actions become simple logical progressions. What’s especially important to remember is that this practice isn’t about using speech to affect society, it’s about speech being used to warp the individual mind towards hate through association, a process that results in societal oppression. When you speak someone’s sub-humanity into personal existence, it becomes real — something you believe and accept. When someone decides they’re allowed to harm anyone they understand to be “less than,” there is no stopgap preventing that person from committing terrible actions. When a person is equal to an animal, their rights to respect, self-determination and life are forfeit.

Rwanda. Germany. Guatemala. Armenia. Bosnia. Darfur.

The American South. Manifest Destiny.

Death, destruction, indescribable damage, all at the hands of those with an entrenched belief in their higher humanity. You don’t need to compare those you wish to oppress to animals; it just makes everything else a hell of a lot easier. In this piece, we’ll look at examples of how this practice has been used throughout history and why the comparisons work to such horrific effect, by first turning people into creatures, and then creatures into objects of hate.

What It’s Like to Be Dehumanized | Source: © The Atlantic/YouTube

While one might imagine that such dehumanizing rhetoric would be universally condemned as horrific — due in part to history and in part to their shock-value — others are so normalized that their harmful origins seem to no longer matter. I was around eight when I first learned that “bitch” was both a bad word to call a woman and the scientific term for a female dog. It was clear that it wasn’t a word I could say without getting in trouble, so I added it to that pile and simply moved on; looking back, it’s the kind of thing that would be confusing enough to interest a more curious child. Considering it now, especially in a climate where the word’s been reclaimed by some women and femme-identified people as a moniker of empowerment, the dehumanizing nature of the term sheds a light on the insidiousness of animalization. Dogs are seen as unruly, improper creatures; combine this characterization with the stereotypical sexual and hormonal assumptions of women, and you have an insult that marks a human being as a breeding device in need of training. In the Western framework, both dogs and women are considered property, and so women are shamed and demonized for independent actions; especially threatening, it seems, are sexual expressions of freedom and autonomy.

When a person is equal to an animal, their rights to respect, self-determination and life are forfeit.

Over the past century, the work of feminist movements has resulted in major societal shifts, and while the reclamation of the word bitch into a term of empowerment stands as a minor victory in the ongoing war, it’s an example of one way this kind of practice can be countered. The reason I started with “bitch,” however, is that its normalized nature makes it an uncomplicated introduction to the idea; when race and ethnicity become involved, when some of mankind’s greatest atrocities are on table, things get more difficult. Those whose interests are aligned with maintaining racial hierarchies utilize language to create social realities where they can conduct evil without interference. The words and ideas I want to explore are no longer allowed in polite society, but their impact remains in our consciousness, and many, many people still live with the scars.

Reagan called African delegates “monkeys” in recording | Source: © CBS Evening News/YouTube

Just this last summer, audio footage of then-Governor Reagan and President Nixon from 1971 was released, and one particular exchange highlights an example of animalized dehumanization that has stood the test of time. On the recordings, Reagan, frustrated by recent events at the United Nations, remarked how irritating it was to witness “those… monkeys from those African countries,” some of whom were “still uncomfortable wearing shoes!” Nixon — the lovely fellow as always — can be heard laughing in agreement. The practice of simianization that your least favorite uncle’s favorite U.S. Presidents were engaging in dates back to the first European “explorations.” The disdain for apes themselves has roots in Plato’s declaration that apes were “as to humans as humans were to the gods,” marking us a steep step above our co-primates. The insulting allusion to apes evolved to take on a sexualized nature; women of a base nature saw the larger, primal creature as an object of lust. In his work Metempsychosis, metaphysical poet John Doone portrayed one of Adam’s daughters as seduced by an ape into an unholy union. The convenient thing about dehumanizing people through language is that you can change meaning through simple intent: European women were being attacked via a characterization that would come to be applied to all Black people, especially men.

The controversial Vogue cover featuring Lebron James and Gisele Bundchen in a pose that reinforces racialization and simianization | Source: Jezebel

The African was seen as a beast on two legs, a dangerous animal that needed to be dominated and put to task for his white betters. The African land was a dark continent, a monolith, home of unnatural creatures born from unholy acts between men and beasts. An entire new branch of science — ethnography — was created to soothe the European ego, empirically confirming that the Blacks came from something different, human in basic form only. From the moment that black bodies were forced to share space with white oppressors, their otherness had to be absolute, and so they turned to the monkey. So close to humanity, yet so distant — our genetic relative but intellectual inferior. It’s a creature that we can look at with both fear and a strange pity, safe in the comfort of evolutionary luck. For a people whose humanity was/is seen as both a societal danger and an economic cost, this characterization instilled both superiority and anxiety. The innate fear of black male sexuality within close distance of their white female property drove much of the development of racialized law and civil code, and this tradition carried on well into the colonies of Africa and the New World.

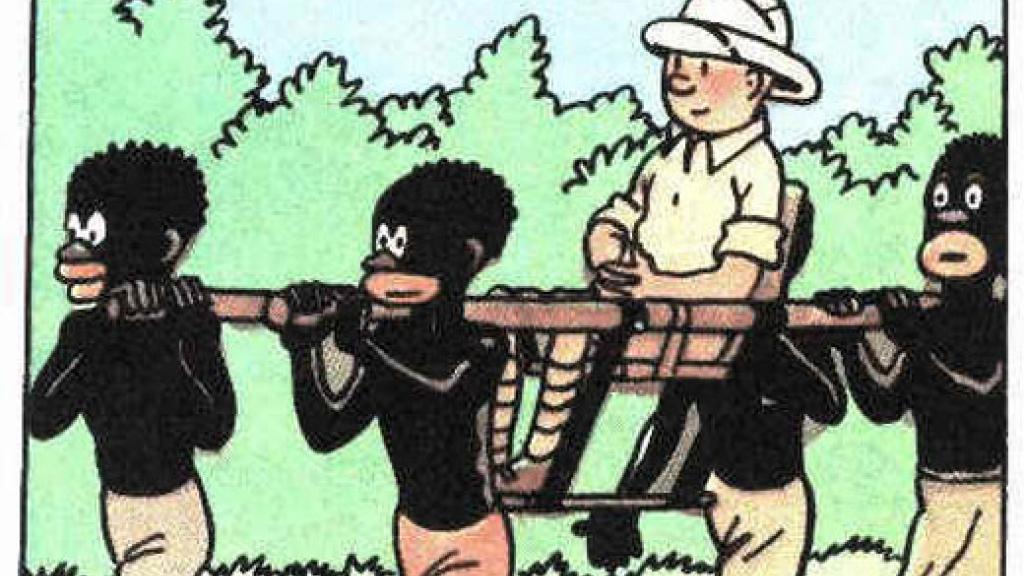

A panel from Tintin Au Congo | Source: The Observers/France24

Media has always played a critical role in driving our culture and the simianization of the black body made multiple famed appearances. Edgar Rice Burrough became one of the most beloved authors of the 20th-century through his most famous work, Tarzan of The Apes, the story of a white man raised among literal apes in the jungles of Africa, creatures which the author presents as far more civilized and intelligent than the Africans who roam the land. The famed Tintin series includes Tintin Au Congo, the story of the young adventurer’s trip to the Belgian colony and his adventures with Coco, his simple, servile, simian-like companion. 1933’s King Kong, the tale of a giant ape ripped away from its exotic home and running rampant through the streets of New York with a damsel-in-distress, stands as a hallmark of American cinema and the latest victim of the Hollywood remake massacre. It also stands as a not-so-subtle racial allegory: the creatures of the dark continent could be tolerable while in chains; once they’re freed into civilized society, chaos ensues and society is in danger. The image of a dark ape holding a screaming white woman in his arms is three steps removed from Birth of A Nation. It is part of the same violent, anxious rhetoric that generated not only the deaths of Emmett Till and the unjust show trials of the Scottsboro Boys and the Central Park Five; it’s the cultural backdrop to the odd looks that accompany every date with a white girl I’ve ever had. Simianization of Black people runs so deep that President Barack Obama and First Lady Michele Obama have been subjected to this same treatment multiple times since the 2008 election, a reminder that even the most powerful individuals exist within a societal context that seeks to diminish their humanity at any point.

Media’s power in this context cuts both ways, as illustrated by Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds. A Tarantino movie about Nazi Germany was certainly not going to mince its messages on racism, and no scene captures that better than the opening. SS Colonel Hans Landa, masterfully played by Christoph Waltz, questions a French farmer about the location of a local Jewish family, and in the middle of his questioning goes into a tangent about what makes him an effective “Jew hunter.” His secret? A begrudging respect for rats. The rat, a filthy, loathsome, hard-to-kill creature, universally despised and credited with spreading plague across civilization; is there any better metaphor for a Nazi’s notion of a Jewish person?

Inglourious Basterds (1/9) Movie CLIP – The Jew Hunter (2009) HD | Source: © Movieclips/YouTube

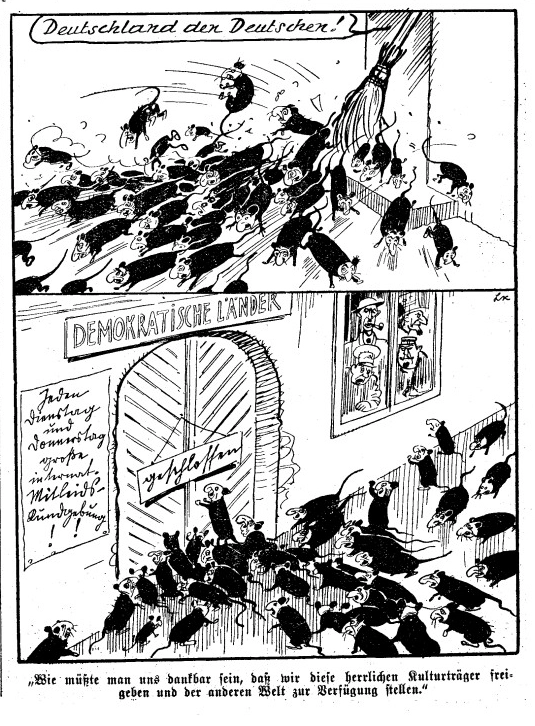

In 1909, the American satirical magazine Puck published a cartoon featuring Uncle Sam playing the role of Pied Piper and leading a throng of immigrant rats — “thieves” and “criminals,” as the author refers to them — into their new homeland. This image of the infestation, the invasion of something unwanted, strikes a powerful tone given our natural distrust of rats. It is common belief that the Bubonic Plague that ravaged Europe was spread on the backs of rats, brought back from foreign lands. We see them as violent occupiers of our city streets and countryside fields even though they were here long before us. They’re survivors, constantly hunted for no discernible reason, and constantly repopulating, thereby earning the Colonel’s “respect,” even as he plays the role of the hawk.

Those whose interests are aligned with maintaining racial hierarchies utilize language to create social realities where they can conduct evil without interference.

Racist cartoon depicting Jews as rats from the 1939 issue of Austrian newspaper Das Kleine Blatt | Source: Huffington Post

Nazi media and propaganda contain no shortage of comparisons between the Jews and rodents; some of the most disgusting images from the period show the bodies of rats with grotesque heads and Stars of David. The 1940 film Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew) paints a picture of a strange, ugly people who choose to stay cramped in the ghettos of Poland and spend their time bartering, scheming, and committing heinous “religious” acts, and then literally transforming into vermin before the viewer’s eyes. The most insidious aspect of the film is the implication that these people exist “behind the mask of the civilized European.” The Germans feared the Jewish physical resemblance, their ability to pass as standard white, so much that they invented an entire[ly false] scientific framework to detect Jewish defects in their population. The strict genetic legal code enforced in The Third Reich was a direct response to the inability to distinguish between human and subhuman. Whereas the Black body offers an immediate route to visual discrimination, a Jewish person could fully infiltrate German society simply by existing; while even white-passing Blacks had to fly under the radar, a Jewish person would only have to make minimal lifestyle changes to avoid drawing the ire of the Third Reich. The infamous Jude patches were a remedy, a way to mark their prey. The Nazis used the image of the rodent to channel the pre-existing anti-Semitism of the time into a direction suitable for their darkest plans.

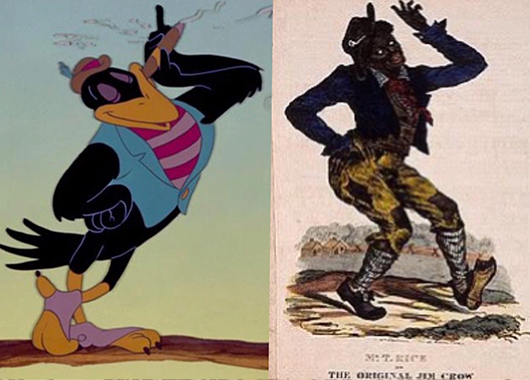

Now, seeing as how I just spent most of this piece walking you through the dehumanization of Blacks and Jews, let’s talk about something a little more fun: The Walt Disney Company. Before I put the Happiest Media Conglomerate On Earth on blast, let me state for the record that I am such a slave to Disney content that I paid $140 for 3 years of Disney+ and am fully committed to watching Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker in theaters, guaranteed disappointment be damned. I love Disney, you love Disney, people who say they hate Disney love Disney: it’s a simple fact of life. But what happens to that love of Disney when I think about the shuckin’ and jivin’ crows in Dumbo? The scheming, slant-eyed Siamese cats from Lady and The Tramp? The entire runtime of Song of the South? With a filmography dating back to the first World War, the fact that a good handful of Disney animation contains extremely racist depictions isn’t surprising. What matters here, however, is looking at how these depictions work as cultural conditioning, particularly on children.

Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah (Original) | Source: GeezersPlaceORG/YouTube

Racialized crows from Dumbo and Jim Crow imagery | Source: Medium

When these films incorporate gross racial stereotypes as simple, benign entertainment, it enshrines them in a protective layer of innocence. While I look at a slow-talking, lazy bird literally named “Jim Crow” and see a Klansman laughing, someone who grew up with the depiction sees a funny character in a movie about flying elephants. The conversation has nowhere to go because they fundamentally see harmlessness where someone else sees horror. Even worse, they might suggest that whatever problematic elements there might be, the children for whom it’s meant won’t be able to understand it. The irony of the harmful behavior being taught to children and then being dismissed as too childlike to cause harm is something that cannot be lost on us, otherwise this practice will only continue. Depictions that otherize people create images in developing minds that manifest as the worst kind of thoughts and actions later in life. It should be noted that Disney themselves have recognized this and, in addition to burying Song of the South (there are very happy slaves and talking bunnies, 10/10) in a hole, they’ve also added disclaimers to most of their offensive content denoting the time of creation and current regret. There are many lessons that can be learned from these films and their place in the cultural pantheon, but the most important lesson must be that when racism is framed as comedy, it makes the conversations hard to take seriously from the people who need to hear it the most.

The results?

I’ll let you decide for yourselves.

Animalized dehumanization transforms the hierarchy of the natural world into a tool of hate. It reduces people to a form that justifies the cruelty of others. It serves the purpose of those who do harm, infecting the cultural space with images and thoughts that lead to institutionalized oppression, societal dismissal, and, on far too many occasions, death. In all cases of dehumanization via language, the power of the word comes from the myriad of systems — cultural, social, economic, political — that enforce the worldview behind it. As we continue the work of dismantling those systems, we must remember to use our language in that service, to uplift our fellow humans and validate their personhood. We must never, ever forget the sameness that we share, and always be ready to defend against those who would see us less than human.