CONNOR BUCKLEY

Chris Hemsworth being directed by Michael Mann on the set of Blackhat | Source: Indiewire

Watching a film by Michael Mann, especially his more recent output, requires surrendering to his stylistics. The filmmaker behind such beloved crime thrillers as Heat and Collateral sets his films within alienating or downright oppressive environments, largely to reflect his characters’ senses of being locked away from the rest of society at large. Many of the men who feature in Mann’s contemporary dramas — James Caan, Tom Cruise, and Al Pacino, for example — are fairly notorious, and share common personality traits — being stoic, if prone to impulse — as well as similar physiques. Yet within these films, no one is working to draw attention to themselves. His characters are driven to hide away in the shadows, neglecting friends and loved ones, devoting all efforts towards their trades of choice. The audience is trusted to use these men as a lens to view the narrative, yet they remain enigmas, their backstories becoming noticeably thinner as Mann’s filmography progresses, and their individual perceptions of the environment taking priority.

Looking back, Mann’s 1981 theatrical debut Thief has a straightforward plot: James Caan’s Frank is a safecracker looking to secure a dream future, and a mob boss enlists him, telling him that if he goes along on this last job, he is set for life. Jump 24 years later to Miami Vice (the film, and Mann presents a noticeably more convoluted plot wherein undercover officers Sonny and Rico (Colin Farrell and Jamie Foxx) are frequently brought into meetings that bombard the viewer with insider police and drug trade terminology.

Miami Vice (2006) Official Trailer #1 – Jamie Foxx Movie HD | Source: Movieclips Classic Trailers/YouTube

The film makes its instantaneous nature aware from the start, smash cutting from the Universal logo to an in-progress prostitution sting on a busy nightclub dance floor. That it can be difficult to keep track of the larger narrative leads the viewer to draw their attention more towards the camerawork, blocking, and scenery. Mann’s distinct digital look — something he first experimented with in Ali before becoming his primary format — becomes more apparent, and the viewer begins to notice how much the handheld camerawork, sporadic focus, and extreme blending of colors influences the meta narrative. Characters seem to fade into the background, absorbed into crowds and neon landscapes that themselves become increasingly irrelevant.

Source: glazy_uk/Instagram

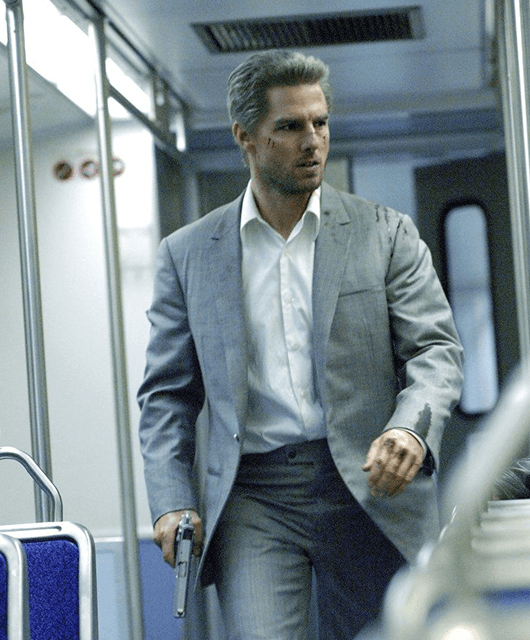

Tom Cruise in Collateral | Source: Pinterest

The concept of characters quite literally blending into their surroundings is not a new technique for Mann; his 1987 Red Dragon adaptation, Manhunter, positions William Petersen’s Graham against backgrounds matching his pastel shirts and ties, mirroring his attempts to conceal his quiet obsession with serial killers. Robert De Niro and Al Pacino in Heat exclusively dress in shades of grey and black to indicate their devotion to the seedy world of cops and robbers as they navigate the sterile Los Angeles nights, and in Collateral, Tom Cruise’s Vincent, a mercenary-for-hire completely shut out from any real human connection, is clad in light grey and goes so far as to pair this with grey-dyed hair, making him appear more an abstraction than a human being. Like the characters it hosts, Los Angeles in both films is displayed in multiple lights, the sprawling city suddenly shutting down or demonstrating itself largely indifferent to the characters the audience is prioritizing, their plights only of concern to authorities or others watching in secret. It is at once alive but motionless — Vincent opines: “17 million people. This has got to be the fifth-biggest economy in the world and nobody knows each other” — reflecting the dormant states of its characters.

It’s important to acknowledge that Mann’s films do hint at a propulsive hope for change and innovation. Thief demonstrates this by following up a scene where Frank admonishes his girlfriend Jessie (Tuesday Weld) for not realizing he is involved in crime with a very open, upfront conversation in a diner overlooking the highway. Frank invites Jessie to be a part of the life he longed for during his years in prison, guaranteeing her that there is a future ahead. As he monologues about his past, we note his silk shirt, gold watch, and chukkas that are prominently displayed as he kicks his feet up on the booth, indicating to us an affectation of cool that he has held onto throughout his arrested development. Beneath the style lies his motivation: a kid who wants to grow up. More importantly, however, is the background: Frank and Jessie are seated directly in front of a highway stretching out into the distance; their road ahead — as Frank sees it — is there, just out of reach behind the glass.

Thief – Diner Scene – James Cann & Tuesday Weld | Source: makemehavefun/YouTube

This image of a far-extending landscape, like many of Mann’s stylistics, is often repurposed as a way of indicating the protagonist’s longing for new purpose, and it too has become something more distorted, best summarized as a formless escape. In Heat, De Niro’s Neil looks out from the windows of his unfurnished beach house at the sea, his gun in the foreground, a recreation of painter Alex Colville’s “Pacific” demonstrating how crime is his lone possession, a reminder of his motto, “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything that you are not willing to walk out on in thirty seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” A 2002 profile of Mann by Senses of Cinema’s Anna Dzenis classifies Heat as a “film laden with death and a sense of sad inevitability as the characters wander around as phantasmal presences, finding each other only to lose each other again.” The struggle is reinvention under circumstances which actively reject any hope of transcendence. Characters throughout Mann’s films are threatened with their lives being stripped away, imprisonment, “gladiator academy,” and general nonexistence. No matter where you are, loss is universal and with time and perception accelerating, it seems everything can fade away in an instant.

Characters seem to fade into the background, absorbed into crowds and neon landscapes that themselves become increasingly irrelevant.

As Mann moves his crime thrillers to the 21st-century, it’s no coincidence that his next professional criminal — Collateral’s Vincent — functions this time as an antagonist. Vincent is the end product of living a life by Neil’s motto, filled with unspoken and barely-glimpsed regret. In a subversion of Mann’s previously demonstrated story structures, Vincent’s philosophy is not his primary undoing. Rather, the acceptance of existential dread in an uncaring universe that he espouses unintentionally inspires his hostage and the movie’s actual protagonist, “part-time cab driver” (of 12 years) Max (Jamie Foxx), to take charge, since nothing truly matters. The point of the Mannian crime protagonist as it exists up to this point has been made, and like Max’s arc here from long-term procrastinator to “improvise, adapt to the environment, shit happens, I Ching” pupil who can perceive and reject the wallowing existence Vincent inhabits, we sense a shift into immediacy.

In a broader context, the significance of Miami Vice’s cold open and general presentation is clearer and more impactful. During a meeting with an informant where all involved are warned that to go undercover is to risk destroying one’s entire life thus far, De Niro’s Neil’s gaze out towards the sea is reprised by Farrell, but this time the scene continues. A reverse shot follows the glance out to the horizon, presenting the audience with a view of his face, which suggests uncertainty yet anticipation: Sonny is considering what it will mean to reinvent himself as part of the assignment. Aware he is under surveillance and understanding that he is going to be dealing with prominent criminals, he comes to embrace the fleeting nature of the moment to the point of destruction, abiding by the motto “Time is luck.” It’s a desperation that in the end seems to not matter as the film closes — like it started — mid-action, but to him, each moment was new, lived.

Miami Vice (Final Scene) | Source: adriandg/YouTube

Farrell’s Sonny transcends Caan’s Frank from Thief’s preoccupation with a perfect future so antiquated it’s embodied in a crude collage of magazine photos, moves ahead of Neil’s wavering commitment to his past motto, and sees not just dreams on the horizon, but a new, feasible opportunity. This is practically foreshadowed in Collateral by Foxx’s Max, who “takes a vacation” from the bustling L.A. streets every day by staring at a postcard of an island in his cab’s visor mirror. Still, though, Sonny will have to remind himself his anonymous freedom remains a visage, that personal mirage of a fantastical island, to be swept away with the tides. As the dream became something more realized as a possibility, however temporary, we see that its form becomes less material and more like a lust for the experience of being. From this comes Blackhat, a crystallization of the subjective experiences, embracing spontaneity, nonexistence, and life as eternal reinvention.

Blackhat – Official Trailer [HD] | Source: © Legendary/YouTube

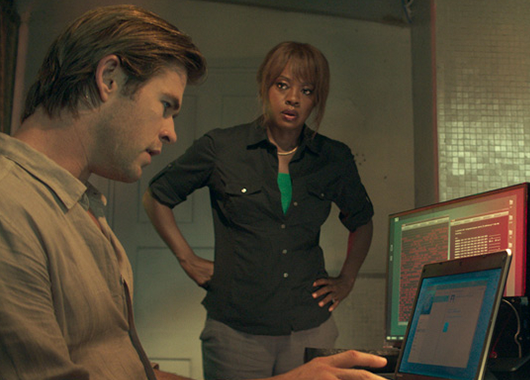

On the surface, Blackhat is a globe-trotting actioner about hackers, mixing in elements of 1970’s paranoia thrillers. To the general public, it is most notable for starring Marvel icon Chris Hemsworth as Nicholas Hathaway, a convicted coder enlisted by the Department of Defense and the Chinese government to track down a mysterious cyberterrorist. Hathaway’s sole companions are former M.I.T. roommate turned captain in the People’s Liberation Army Chen Dawai (Wang Leehom), Chen’s sister, network engineer Lien (Tang Wei), Special Agent Carol Barrett (Viola Davis), and U.S. Marshall Jessup (Holt McCallany). A team is assembled, and from that point on, the location is constantly shifting and the threat of another hacker attack — and an ambush on Hathaway and crew — looms closer and closer.

Chris Hemsworth and Viola Davis in Blackhat | Source: The Mary Sue

Mann drives Blackhat via pure acceleration. The opening scene, in which a nuclear reactor cooling system is sabotaged, demonstrates in a creative CGI set piece how much damage a single line of code can wreak, and how constant data streams in the background manipulate manmade environments, placing humanity at a greater vulnerability than ever before. The greater ability to influence is constantly utilized by the main team to gain an advantage: Davis’ Barrett needs information from an official at a tech company, so she implies a single phone call to the news regarding his withholding information would publicly destroy his reputation within the next 12 hours. This is literally demonstrated when Hemsworth’s Hathaway utilizes a keylogger to obtain a password: control, one’s very gestures and movements, can be at any person’s fingertips. The film is not putting forth a moralizing, “tech is bad” message or coming out in support of government surveillance. Rather, it is a film perplexed by the scope of this control and the natural fear it instills once it’s clear that the stakes are this high. The antagonist is a person, played visibly by Dutch actor Yorick van Wageningen, but that threat feels like a mystical force, present in each second, driving in that existential terror. Yet with this fear comes a heightened sense of importance to all that is encountered. If all is gone in an instant, then within that instant, what matters is what is taken in.

Real Hackers on the Authenticity of the Movie ‘Blackhat’ | Source: actionzone/YouTube

Hathaway’s journey in Blackhat is about survival. While in prison, he is relocated to another cell, and his polaroid photographs, the lone material connection the viewer has to see his past, are cast aside and stomped on by guards. Upon being released, it seems as though he is free, as he embraces Chen (Wang Leehom), this moment framed with extreme shallow focus, their hug the only thing of note. Yet just after this, Hathaway walks along a tarmac towards a plane that will supposedly take him to tomorrow, only to stop. He feels no joy from his imminent freedom. In the stillness, it becomes apparent how grey the sky’s hue is and the score settles and drones. The focus shifts to emphasize the negative space as the next shot frames only half of his face. Cut to a close up from behind, pressing in so tight that his hair is practically invading the audience’s space, and he is surveying the empty road, radio towers, and distant mountain range. The shallow depth-of-field this time, with no one around, reinforces the intensity of his sense that outside is as much captivity as inside. He lives long only to grow more detached, more isolated, and though he never expresses extreme fear about it, his release is only guaranteed if he succeeds — but released to this?

From this comes Blackhat, a crystallization of the subjective experiences, embracing spontaneity, nonexistence, and life as eternal reinvention.

The outside world of Blackhat, in all places, reads as claustrophobic. Buildings tower over, open valleys are commodified, hubs for mining operations are laid out like underground catacombs, and along the docks, shipping containers filled with indiscernible amounts of unimportant materials form labyrinths for the characters to dart through in search of the solution to it all.

Behind the Scenes of Blackhat – Hong Kong [HD] | Source: © Legendary/YouTube

Each new cityscape, from Chicago to Hong Kong, is only allowed to breathe so far as to assure us that, yes, there is life there, before the space exists solely to be navigated, and the search suffocates as it becomes clear that we can never comprehend it all. Characters’ reflections in windows appear as ghostly forms over indeterminable city lights, resisting space. Outside is a mass of information sprawled out and endless, like code, overwhelming and impossible to internalize every piece as it flies by the eyes. What does it matter, if it’s only there and then we are gone and it’s gone?

On the tarmac, Hathaway is processing this insurmountable angst at a world going on without him and not needing him, and then a light brush on his shoulder from Lien (Tang Wei) breaks his trance.

To Hathaway, this momentary gesture is a shattering of and reminder of what reality — literally what is corporeal — can still be. Sitting down later with Lien on a stakeout in a small Korean restaurant, he essentially reprises the speech Frank gave in Thief. Time is unimportant, he claims. He worked his own program in prison, working out his body and mind, like how Frank made sure to divorce himself from feeling in order to fight off other prisoners. “I’m doing the time, the time isn’t doing me.” Lien’s sole response to this is an unexpected reminder: “Open your eyes.” Compared to Thief, this scene is stripped away of the dreaming and the future that Frank planned, and the location is a generic restaurant in the middle of nowhere, because this all has been seen before. For once, a protagonist cannot dwell on their past, the important thing is to move. The experience remains an abstraction, but what can be held onto is physical, real.

In all the invisible influence, and in all the dissolving of faces and spaces, and in all the dread of what has been cannot be again, the world becomes as you make it.

Blackhat then throws the audience into a romance between Lien and Hathaway that was up until this point only hinted at in quick lines and glimpsed mainly through how they viewed one another: how she remarked on his appearance compared to his mugshot or how he gazed at her necklace and hair as they rode in a cab to the restaurant. Just before this, the two are told they will be departing for a meetup in China the next morning, and barely a minute later, they are in bed, as Hathaway opens up about how he would replay memories in prison to prepare for his release… and then the audio of this talk fades. None of this is important to the viewer; only the connection they share, simple and impulsive and beautiful and above all, theirs. A movie about rapidly divulged information and the ease of accessing it denies the viewer this moment, because it is just that personal, something that this time we, not the protagonist, have to imagine.

Tang Wei and Chris Hemsworth in Blackhat | Source: IMDB

The intersection of real and imagined and the transformation of that into motive recurs throughout the film. Barrett is motivated to pursue the cyberterrorist to avenge her husband’s death in 9/11, and in an unspoken second during an intense confrontation, eyes an enormous, anonymous tower in Hong Kong, ascribing infinite personal meaning to it. In all the invisible influence, and in all the dissolving of faces and spaces, and in all the dread of what has been cannot be again, the world becomes as you make it. Oftentimes that meaning is based in the most basic impulses, namely desire. Hathaway correctly surmises that the lead hacker wants nothing to do with politics or money, it’s just power. Barret desires a conclusion to her trauma, and Hathaway and Lien desire a new experience. The latter two can find connection. Their reality is togetherness understood only by them, possibly doomed, as Chen notes that while he has “rarely seen her happier,” Hathaway could just as likely be thrown back in prison if their mission fails, and she would be heartbroken or forced to wait years to see him again. In all the phantasmal allusions witnessed throughout Blackhat, where characters are so often are framed by windows, their reflections barely visible amidst endless city lights, it would make sense to view this as a culmination of what really matters. Two souls, uninterpretable, unexposed phantoms, prepare for the next world, faith being one of their only reassurances that it exists.

[Mann’s] characters are driven to hide away in the shadows, neglecting friends and loved ones, devoting all efforts towards their trades of choice.

In embracing his stylistics and moving further from a constructed reality, Mann has produced something ethereal, an exploration of life and death. And death is showcased in a harsher light than Mann has done before. His primary and secondary characters alike die with intensity, thudding on the ground as their bodies give up, a machine with its pieces broken down, powering down forever as their name is screamed for the last time. To live in regret, as Frank, Neil, Vincent, and, yes, Hathaway do is to fear destruction, and Blackhat’s world is filled with constructs and indescribable histories that will outlive all. Its climax takes place against an unexplained religious ceremony, thousands of people moving in celebration of beliefs and tradition that have spanned generations. Our beliefs and craft have been built to outlast our time on this earth: a hard drive in the nuclear plant survives fully intact while nearly all inside suffered, and in our modern lives information is processed, interpreted, and tossed aside faster than ever. The antagonist remarks that his control extends so far that if he simply ignored something, it would not exist, but this ability is rooted in human psychology, and even made physical, extended out to the world at large; one still cannot erase the entirety of being. The film’s image of an Earth with visible data streams is so complicated as to appear completely alien, and yet within those streams are lives and voices, surviving. Evidence of reality, surviving, heard, seen, and felt. So too is the body, a physical vessel to express the soul.

Perhaps another reason Blackhat resonates is that it likewise was cast aside, given a short theater life, and though a director’s cut exists, as of this writing that cut is not publicly available. A deeply humanist work dismissed, but to some who saw it, it lives on. Within it appears the decisive conclusion to all of Mann’s protagonists’ fears about loss. As Hathaway holds Lien aboard a plane, both finally commit to leaving all else behind, she stares out the window at a past world she’ll likely never know again. We understand this as an escape, but it is an illusion: the escape out to somewhere in the sea is realistically impossible.

No matter where you are, loss is universal and with time and perception accelerating, it seems everything can fade away in an instant.

Max from Collateral’s dream island is significant to him, but he cannot physically go there, just as Neil from Heat cannot let go enough of his criminal life to do so, and Sonny from Miami Vice understands such journeys are on borrowed time. The stories are retold but viewed in different perspectives, analyzing different moments and lives to understand the characters’ world-views as they twist and turn. Lien’s eyes well with tears at the loss she has endured — this escape is as much circumstance as it is choice — but Hathaway’s embrace assures her he will never let go. The flight will end, the island will vanish, and they will have to navigate these spaces again, but they will land with a transformed perspective, akin to Mann’s evolving style and format shift, allowing for a new world. Metropolises will remain dizzying, and the world continues to transform into capital as mystery and parts unknown diminish and become resources, yet the soul inhabits an existence that cannot be touched. The ability to determine what exists and does not is most decided by the individual. It falls to Lien and Hathaway to construct a new life.

BLACKHAT michael mann 2015 plane scene | Source: Nicholas Lemoine/YouTube

For once, a protagonist cannot dwell on their past, the important thing is to move. The experience remains an abstraction, but what can be held onto is physical, real.

Mann’s immediacy becomes not a fear, but an acceptance that an ever more confusing world will eventually swallow us up, but we can navigate it with a reassurance of the existence of life beyond understanding, even in the short time we are given. That is our control over our personal machine: though identity itself becomes commodified, how it operates never can be. Here, the world will fade, but we choose to stay.