ALEKHYA MUKKAVILLI

When I land in Delhi from New York after over a year since my last visit, I mentally prepare myself for the traveling I will be doing in the week ahead.

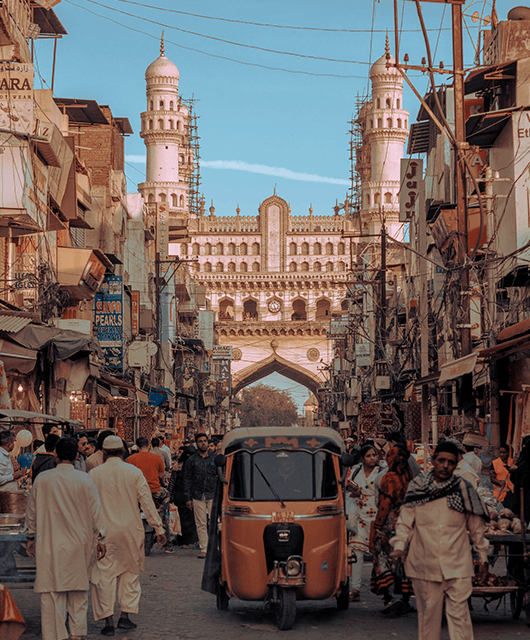

Charminar, Hyderabad

The day after I return home, my parents and I board a plane for Hyderabad, where we spend an extra hour driving through the old city. I try to take photos of Charminar and Hussain Sagar from my phone, and later realize that all the photos have car mirrors in them.

Once we arrive at my grandparents’, we eat lunch. I meet my grandparents’ friends. They tell me about their old age and how their lives have changed, and I try to mentally record their answers to my questions. That night, we go to a temple where my grandmother has organized a special ceremony. During this ceremony, a priest adorns a statue of the Hindu God Hanuman with a garland of vadas — fried lentil snacks. Later, the vadas are welcome accompaniments to our dinner.

The next day after breakfast, we’re off again, on an even tinier plane, to a Hindu pilgrimage site called Tirupati. The town that the temple is in, Tirumala, is India’s cleanest city. It smells holy. The people who live here emanate the sort of indifference towards modern day obsessions that I associate with people who have a connection to a higher power. I see hundreds, maybe thousands of people, pray together. At the end of the day, everyone in line for prayer gets their two seconds in the Sanctum Sanctorum, the holiest part of the temple complex. As I watch people chant, I begin to think of why each of my experiences in India seems so profound.

Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam Temple (English | Inside National Geographic Full HD) | Source: Technical Geeks/YouTube

Whether Indians are atheist, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Zoroastrian or Buddhist, their belief in “something else” or “somewhere else” is a constant wealth of peace. The idea that there is some universal truth to any human experience, and the good and bad interpretations of religion and spirituality that accompany this notion, saturates my experiences in India with so much meaning. It’s why I haven’t fully considered the United States my home.

I have spent the past six years as a college student and then an adult-in-training in New York. I grew up in Ho Chi Minh City and Bangkok, and I graduated from high school in Delhi. To further confuse things, I was born in Bangalore, a Southern Indian city that linguistically and culturally has little overlap with Delhi and the National Capital Region. I don’t speak any Indian language, my American accent has gotten thicker, my awareness of Indian politics has ebbed away, and my spice tolerance has wilted.

[Art] and human alike are in a state of perpetual spiritual motion, seeking to understand what the feeling of belonging could mean.

When I go home, it is imperative to me that I spread myself thin, that we travel to different places and eat every type of fried delicacy that Mother India has to offer. It’s science — that’s the fastest way I will reabsorb the essential nutrients that tie me to my country.

On the second to last day of my trip, my parents, a family friend, and I pile into our car for a two-hour drive to see the 2019 Indian Art Fair. Within 30 minutes of being there, I’m drawn to three watercolor pieces displayed at the Vadehra Art Gallery’s stall.

Source: India Art Fair/Instagram

Despite being two-dimensional and not having any explicit sense of physical or metaphysical context, these watercolors convey a sense of constant motion. As a result of the paintings’ festive colors and sporadic use of text, I’m inclined to try and find a story in the way that darkly colored figures interact with their surroundings in each work. Upon closer inspection, however, I realize that these paintings only provide the illusion of a narrative plot.

In a piece called Corridors, dark figures that resemble women migrate from the south west of the page to the north east in groups, all the while traveling through bright regions of blues and greens, and neutral regions of brown. The piece is littered with lines, connections between points labeled “corridor.” These women have their backs to the viewer and seem as if they are in a perpetual state of migration, moving even once they leave the confines of their paper.

Whatever is Here, 2006, by Arpita Singh | Source: art.fervour/Instagram

In another watercolor titled The Embroidered Continent, the artist depicts a map in vibrant pinks and blues. Although ostensibly pleasing, the content of the image is not as happy as it seems. The blues are littered with shark fins, and the word “sea” labels the waves that surround the island so frequently that it seems to trap the contents of the embroidered continent. The continent itself is a mix of human-made bridges and tunnels and unconquerable swaths of green and empty space. Medallions that look like colonial currency are scattered across the island and take up prime real estate next to rich shades of the continent’s greenery. The continent is at once trapped from the outside and infiltrated from within.

My eyes come to fall upon the gallery’s description of the watercolors and the artist, Arpita Singh. As I learn from reading the description, Singh’s use of cartographical features distinguishes her art. In signifying elements of maps, her artwork conditions its viewers to associate the sentiment of each individual piece with the concept of a location. Suddenly paths of movement that lack any contextual details are assigned emotional ones; horizonless spaces could capture the feeling of escape, and lush greens could be the feeling of the country before it was colonized.

ARPITA SINGH: A RETROSPECTIVE 30 January 2019 – 30 June 2019 | Source: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art/YouTube

However, the sense of constant travel in Singh’s pieces means that they are not just about the location themselves. Be it the positioning of figures across each of her watercolors, or the roads, bridges, or seas through which these figures travel, the constant sense of transition in Singh’s artwork raises the importance of place without depending on the specificities of a single location or point of origin.

In this sense, Singh’s cartographies are like fragments of one’s memory stitched together to create a feeling of a place that is distinct from time and space. As the gallery’s description highlights, Singh’s abstract vision of maps and travelers raises questions around the need for a journey:

“Be it cloaked women, navigating literal and metaphorical corridors, imagery of landmasses surrounded by water, cross roads, settlements, human figures in transition through the modes of transport… All these works surround the viewer with an observation point which induces the question: where does one truly belong?”

Wouldn’t we all like to know.

Whether Indians are atheist, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Zoroastrian or Buddhist, their belief in “something else” or “somewhere else” is a constant wealth of peace.

When I return home that day, I send the statement to my sister. After about a month of being back in New York, I reach out to Vadehra Art Gallery and find myself in the unimaginably gifted position of being put in touch with Arpita Singh.

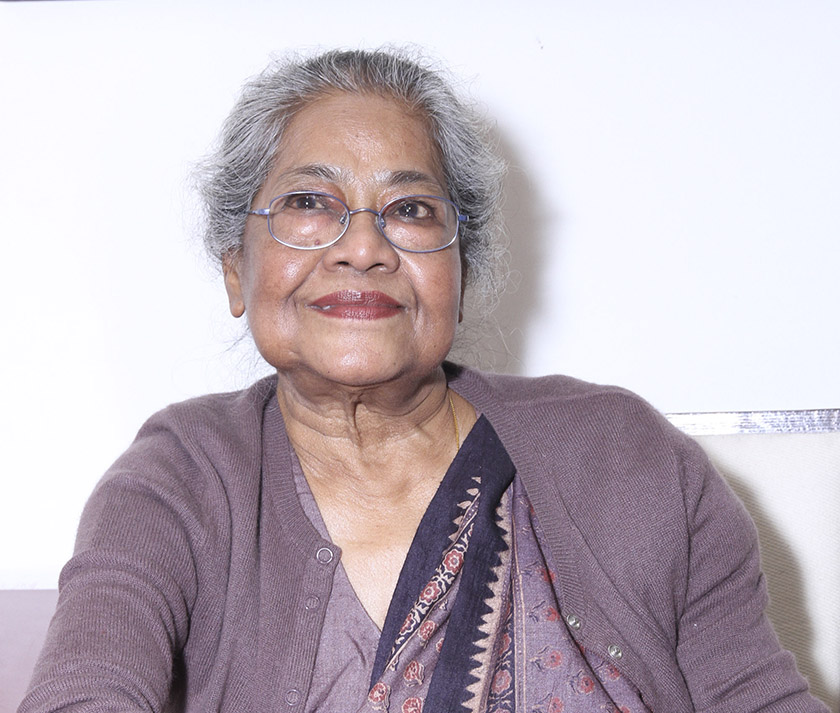

Arpita Singh | Source: Vadehra Art Gallery/BlouinArtInfo

From my own research, I know that Singh, born in 1937, has lived through some of the most formative moments of India’s modern history. Independence, Partition, the rise of the Indian National Congress, and the birth of progressivism gave way to a new era of South Asian Art. Singh and her contemporaries use elements of abstract art, minimalism, and traditional Indian art to evoke the sensibilities of a modern Indian nation built for the people and which continuously grapples with whatever that is supposed to mean.

On the phone she is incredibly kind and patient with our static-filled interview (which eventually needs to be followed up with an email exchange). My questions to her range from asking about her artistic process and choices, and the themes that she chooses to paint. While laconic, her responses carry a lot of weight in my mind.

Kantha embroidery | Source: Pinterest

After graduating from the School of Art, Delhi Polytechnic, Singh worked in New Delhi and Kolkata at the Weavers’ Service Center. In response to a question I ask about the similarities between her art and Kantha embroidery — a Bengali embroidery technique that binds layers of cloth together — Singh informs me that viewers of her art have made the connection rather than Singh herself. Although, she does concede to the visual and symbolic connection between Kantha and her work.

“Sometimes I use broken lines all over the surface to hold [different elements] together. The threads of Kanthas have a similar function; they hold limp cloth pieces of old clothes together… In my work, too, long lines connect different forms. Making this connection gives me peace.”

The lines are a source of peace to the viewers as well, in that they provide a path, a way of understanding the otherwise incomprehensible fields that envelop the connected lines in Singh’s art. Singh revels in how reasonable these lines seem: “They look like passages, so I name them, as if they are roads, etc. This is a game I like to play.”

However, as in life, the paths are broken. Nothing in Singh’s art is as explicit as we would like it to be. She adds, “But sometimes the roads are disrupted, damaged, broken, one can’t proceed, the journey is abandoned, this is a tragedy.”

[Horizonless] spaces could capture the feeling of escape, and lush greens could be the feeling of the country before it was colonized.

The figures of individuals throughout her art seem to bear the brunt of this tragedy. When I first ask her about the migration of women in her art, Singh speaks to the realities of displacement:

“Throughout history, and even now, women are most affected by migration. I feel that strongly and it shows in my art.”

I ruminate on this thought. While there is no doubt why Singh was drawn to paint women as the figures in her artwork, the various elements of transportation and human movement throughout her art make it seem that movement is inevitable. I can’t shake the feeling that each piece conveys a more absolute truth regarding the movement of any individual.

Ashvamedha, 2008, by Arpita Singh | Source: Christie’s Asia/Instagram

I ask her whether, beyond political displacement, her artwork concerns itself with universal sentiments surrounding transition and home.

Without hesitation, she says yes. “To me, everyone is always trying to return to the place from which they belong.”

Later, by email, she expands on this thought:

“I think this sentiment applies to everybody, everything. The place of origin is a dreamland. Even when a death occurs it is usually said that the person has gone back. Perhaps it is a continuous search. Because people are forced to migrate (naturally or politically)? The primitives used to carry the bones of their elders with them, so that when they return to their old habitat, the dead elders can rest in peace. This feeling is universal.”

Herein lies the beauty of Singh’s art: neither the viewer who tries to decipher it nor the paintings’ figures who navigate its terrains will ever fully understand what the place of origin is. Instead art and human alike are in a state of perpetual spiritual motion, seeking to understand what the feeling of belonging could mean.

Heart to Heart with celebrated artist Arpita Singh, Padma Bhushan | Source: Art Life Gallery Noida/YouTube

I ask her, maybe more for myself than out of intellectual curiosity, whether these figures are frozen in time, or whether they are part of a larger narrative.

Singh’s response reminds me, once again, that no element of her art can be viewed so simply:

“The female figures in my works are just like any other forms. Each form is important for that particular work to which they belong. I don’t care whether they are frozen in time or part of a larger narrative. They are there because of a certain need. They will vanish when the need is over.”

They exist in the moment, amid a never ending and undefined journey.

Aquarius: Creative (from the Zodiac Series), 1999, by Arpita Singh | Source: mapbangalore/Instagram

Coincidentally, I keep on finding myself in the same exact place. Although, after speaking to Singh and closely analyzing her artwork, I do not feel so wholly lost. It’s made me recognize the moments in my life where I feel my anxiety about home completely vanish.

Herein lies the beauty of Singh’s art: neither the viewer who tries to decipher it nor the paintings’ figures who navigate its terrains will ever fully understand what the place of origin is.

The last time was during my last morning in Delhi. My mother was awake and made me tea. Together we sat in silence with mugs of steaming chai and watched Delhi’s smog spread across our apartment complex, blurring the fine lines of where we were. I closed my eyes and allowed myself one minute to exist in our amorphous living room.

For those sixty seconds, I was home.