ANGELINA CHAIRIL

The year was 2017 and to those of us art enthusiasts, it was the Superkunstjahr, which literally translate to “Super Art Year.” An occurrence which happens every ten years, three of Europe’s most important mega-art exhibitions — Documenta in Kassel, the Venice Biennale, and Skulptur Projekte Münster — all coincided in the summer of 2017. It is the time when many art world people flock to Europe to seek to discover new discourses in global contemporary art — me included.

documenta 14 – learning from Athens (DW Documentary) | Source: © DW Documentary/YouTube

I would also say that 2017 was the year that I realized that my life was at “peak digital.” That is, social media had gone from a platform for me to catch up with friends, colleagues, and acquaintances, to full on Pandora’s box; my content consumption ranges from daily news, memes, and beauty editorials, to recipe inspirations, exhibition previews, and reviews. You name it, I consumed them all.

In an era when you can find almost anything within the abyss of the Internet, when everything exists in digital form, some may find navigating their way into an authentic experience to be a struggle. I couldn’t help but wonder how this era of “peak digital” would impact my highly anticipated first experience of the Superkunstjahr?

Art Trip: Venice Biennale | The Art Assignment: PBS Digital Studios | Source: © The Art Assignment/YouTube

Before I even stepped foot on the European continent, I had read about the exhibitions, seen the list of exhibiting artists, and knew where and how selected works are to be displayed — all from merely scrolling on my phone. I had partially experienced the exhibition digitally, and (unintentionally) found out what the relevant art critic and media outlets thought of the event, the works involved, and their socio-political implications. My inability to control this information intake made the formation of an objective and honest personal opinion challenging. The mass of information prevented me from experiencing the work first, and then delving into criticism.

With whatever naïveté I had left — and hoping to be captivated by encounters with an in-person spectacle — I embarked in search of an authentic experience.

A 2002 10-Euro coin celebrating Documenta | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Created to reflect ‘an enormous hunger and to compensate for the lack of information about international artistic tendencies’ in post-war Germany, the first edition of Documenta motivated 130,000 visitors to visit the city of Kassel in 1955, and this number rose to 891,500 visitors in 2017. With hundreds of artworks on display and about a few dozen exhibitions going on across the city, it is near impossible to recall all of them in great detail, but I would like to focus on one particularly indelible encounter.

At the main venue of the Fridericianum, I came face to face with American video artist Bill Viola’s single-channel video, The Raft. At first glance, the 10-minute long video seemed no more than an enlarged phone screen. Projected on a screen of 396.2 x 223 cm and displayed in a darkened room, the video depicts the struggle and resistance of 19 people in modern day clothes being hit by a violent jet of water, these scenes presented in what looks like a series of still shots in extreme slow motion. Set against a black background, the video blurs into the blackness of the dark room where the video was screened, and they provide stark contrast to the details in color and texture of the subject. All these aspects of scenography combined create an enveloping atmosphere that makes the viewers feel as though they are amongst those standing on the raft.

Bill Viola, Kaldor Public Art Project 21 | Source: © Kaldor Public Art Projects/YouTube

Moreover, the unbearably slow-moving and lethargic scenes disorientate the viewer from their surrounding, and yet you could not look away even if you tried. You are forced to examine every single detail, of each person in the exact moment they were caught off guard by the sudden onslaught of water; clinging onto strangers, crying in desperation in the powerlessness and inability to escape the scene.

A feeling of internal discomfort creeps in, of witnessing the tragedy and not being able to do anything about it. You look around the room and examine the faces of people around you. How would I react if I were one of the 19 people on the raft? Would I reach for the stranger next to me and help them to stand back up? Do other viewers in the room react the same way towards a visual encounter with suffering?

In an era when you can find almost anything within the abyss of the Internet, when everything exists in digital form, some may find navigating their way into an authentic experience to be a struggle.

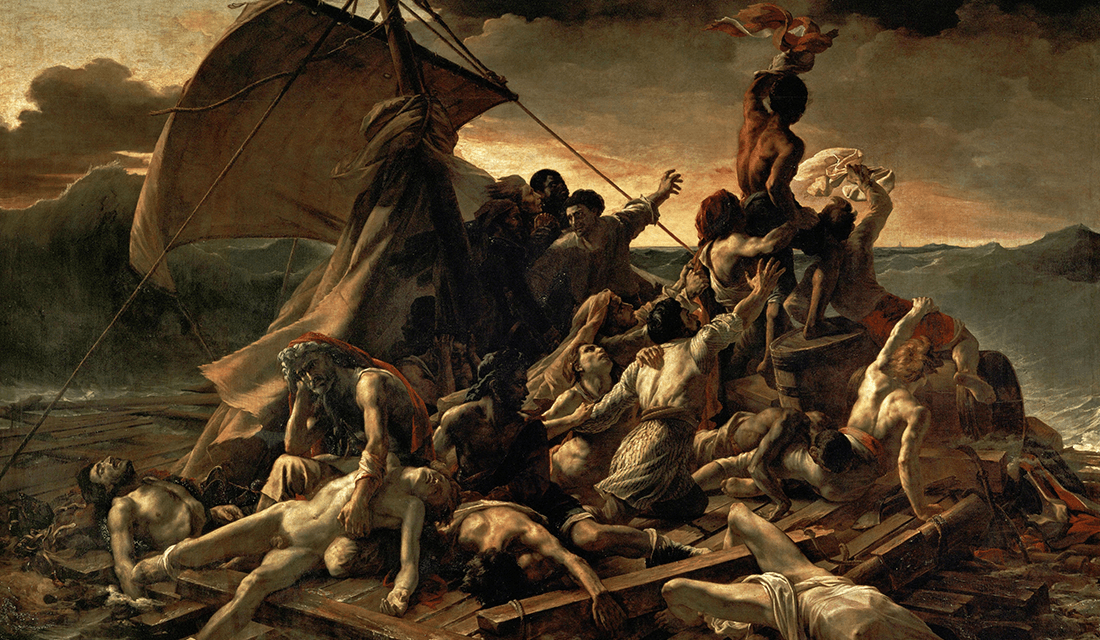

Viola’s The Raft explores the overlapping values and issues existing in humanity. It is a thousand paintings in one frame. It triggers a memory of another space in time and It brought me back to a past encounter with another work of art — Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of Medusa hanging in the Louvre in Paris. Although there was no explicit mention of this association, I couldn’t avoid the mental juxtaposition. It also reminded me of another image i encountered on the internet a few years ago of the late Alan Kurdi, whose dead body was swept away on the shore as his inflatable boat failed to safely deliver him into his intended destination of refuge. Among the group of visitors facing The Raft that day, I don’t think I was the only person in that room who was transported back to memories of this image, and many other harrowing ones we too often encounter in our daily consumption of digital content.

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault | Source: Wikipedia

Yes, The Raft is a work digital in nature, and hence may be easily reproduced and experienced within the comfort of your own homes. And yes, you do not need to travel very far to be moved by an image, or learn of the social implications behind Bill Viola’s work. But to be able to experience such camaraderie from viewing a work of art, and recognizing its symbol of hope and survival in the midst of chaos, is something which I think would be difficult for any digital mediums to translate. That is, standing in a room with other people watching the video is a critical part of the work’s effect.

Nonetheless, there’s no denying the ability that technology has to transport ideas and advocate the democratization of artistic experiences — that mega art events such as the Superkunstjahr could be re-packaged and presented with enhanced inclusiveness. The Indonesian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, for instance, is an appropriate reference to examine this issue.

Tintin Wulia’s 1001 Martian Homes at Venice Biennale 2017 | Source: CoBo/YouTube

Entitled 1001 Martian Homes, Australia-based, Indonesian artist Tintin Wulia presented a mixed media installation to address the issue of borders, migration, identity, and belonging. The series of three artworks — a short film entitled 1001 Martian Homes, an acrylic dome entitled Not Alone and a staircase alongside some round-shaped screens entitled Under the Sun — as a whole envisions how the histories of some families and stories of displacement from present day planet Earth will be told in the hypothetical future, at a period of a Martian Colonization.

The pavilion was presented simultaneously at two different venues in two different countries — the original Indonesian Pavilion at the Arsenale in Venice and at Senayan City Mall in Jakarta, Indonesia. The twin version at Jakarta was identical to its Venice counterpart in terms of its display and layout, and a video footage of visitor’s interaction with the artwork is livestreamed to the other venue and vice versa. The acrylic dome in Venice was even installed with a motion sensor designed to translate movements into the illumination of LED lights on the corresponding piece in Jakarta.

Source: melanisetiawan/Instagram

Ambitious in its conception — which tried to deliver an experience of being in a borderless world — its execution, however, was ultimately lost in translation. Motivated to present forms which catered to the digital aspects of its articulation, 1001 Martian Homes unintentionally neglected to include a sense of place; an atmosphere of being in a particular time and space —that which makes an encounter memorable to human beings experiencing them. In addition to the technical glitches that disrupted the audiences’ experience of the work, these shortcomings in generating benevolent contact with the public were a big price to pay in exchange of democratizing the artistic experience.

But to be able to experience such camaraderie from viewing a work of art, and recognizing its symbol of hope and survival in the midst of chaos, is something which I think would be difficult for any digital mediums to translate.

Site-specific art exhibitions like Skulptur Projekte Münster came about from similar considerations. Every ten years, the whole city of Münster becomes the venue whereby a series of ‘’sculptures’’ and their display on specific sites are designed to pose direct intervention with the city and its inhabitants. Although the event’s name suggests a particular focus in sculpture, the limits of what constitutes ‘sculptural qualities’ have been thoroughly expanded 40 years since its first inception in 1977. The 2017 edition of Skulptur Projekte Münster included several pieces of durational performances, whereby performers and their movement in a confined space were considered as sculptural forms in motion. The definition of sculptural qualities also extended to include large scale installations — where the audience, their experience of the space, and the resulting interplay becomes a most organic form of a kinetic sculpture — demonstrated by French multimedia artist Pierre Huyghe’s commissioned installation, After ALife Ahead.

Pierre Huyghe: After ALife Ahead / Skulptur Projekte Münster 2017 | Source: © VernissageTV/YouTube

Set in an abandoned ice skating rink due to be demolished after the Skulptur Projekte Münster ended, Huyghe explored the possibilities of life forms on Earth through a visual and multi-sensory simulation. As an antithesis to how he thinks the museum is a place of separation, his choice of venue, and the whole of the installation, is supposed to represent continuity. In fabricating a foreign environment, the artist incorporated components such as pathways made of clay, puddles of water harboring algae, and an incubator holding cancer cells. Being in the midst of such an enveloping alien atmosphere with a variety of natural forms makes you feel like you are just a particle in a larger ecosystem. We are ‘forced’ to alter our conceptions on space, and its designated purposes. It was an unsettling, yet sublime discovery — an experience that is heavily reliant on physical presence.

With whatever naïveté I had left — and hoping to be captivated by encounters with an in-person spectacle — I embarked in search of an authentic experience.

I may have learned many things from my daily musings on the Internet, but experiencing art in person has allowed me to ‘’unlearn’’ some things, too, in order to consider previously unconsidered ways of what defines being a human in the world. While I am grateful for the way technology and social media has altered my experiences with art — in many ways unimaginable ten years ago — I still think in-person and in-community encounters are important.

That being said, I think we are still a long way from forging an authentic experience through digital means. When I go somewhere to see art, be it the Venice Biennale or a local gallery around the corner from my office here in Singapore, showing a curated selection from local photographers, I make an occasion out of it. I take the extra time to read the exhibition brief and the artist’s bio. I look at the titles given to these artworks, and think about what they imply with relation to the composition I see before me. I also watch other viewers in the space, and consider their perspectives and ideas. Perhaps it’s the anticipation of physically discovering the unknown which make up half the experience, but digital reproductions of artwork are no substitute for an in-person encounter, and its consumption in the silo of on-screen isolation is but a fraction of the whole experience.

Author’s Notes:

- The upcoming edition of the Venice Biennale runs from 11 May to 24 November 2019. Entitled May You Live in Interesting Times, this 58th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia is curated by Ralph Rugoff.

- The upcoming edition of Documenta will take place between 18 June to 25 September 2022. The organization behind Documenta recently announced the appointment of Indonesian art collective RuangRupa as Creative Director of its 15th edition.

- The next Superkunstjahr will take place in 2027.