T. CHASE MEACHAM

Once when I was in high school I was in the car with my mom. It was late at night and we’d been driving a while.

We were listening to NPR when a program came on called “Polk Street Stories,” a Transom radio special that aired on the show Hearing Voices. It had been created by a young oral historian named Joey Plaster.

The segment told the story of the Polk Street community in San Francisco, based on a series of interviews conducted in 2008 and 2009. Polk Street was a working class queer community — which, like most of San Francisco, had found itself deep in the midst of tumultuous gentrification that threatened to upend the fabric of the community. And, by extension, its residents.

Polk Street Culture Clash, Part 1 of 3: Is it Straight vs. Gay? | Source: UnderTheGoldenGate/YouTube

Recently I had come out to my family as gay. As my mom and I drove, my newfound identify felt heavy in the air.

My mother and father came of age in a time when gay people were largely defined by tragedy.

Gay people were diseased. Gay people were lonely. Gay people were deviant.

The gay rights movement had spent years whitewashing these perceptions, promoting a mainstreamed vision of the community that felt both unthreatening in its familiarity, and unique in its talents.

“Polk Street Stories” did not do that. Here was a story that dove deep into a tragic past. Its subjects — real humans, captured forever in candid, intimate, funny, heartbreaking recordings — came from a generation that ran away from home when they came out to their families. Theirs was a community ravaged by disease. And while the Castro had become a focal point of queer life and sex and politics, Polk Street had become the place for the rest. For people of color; people who were trans; people who were sex workers. People who didn’t fit in anywhere found themselves on Polk Street.

And now Polk Street was changing.

Mom and I drove on.

What happens to the ones who found home there; what of the lives that thrived there, or died there?

Source: Swedian Lie

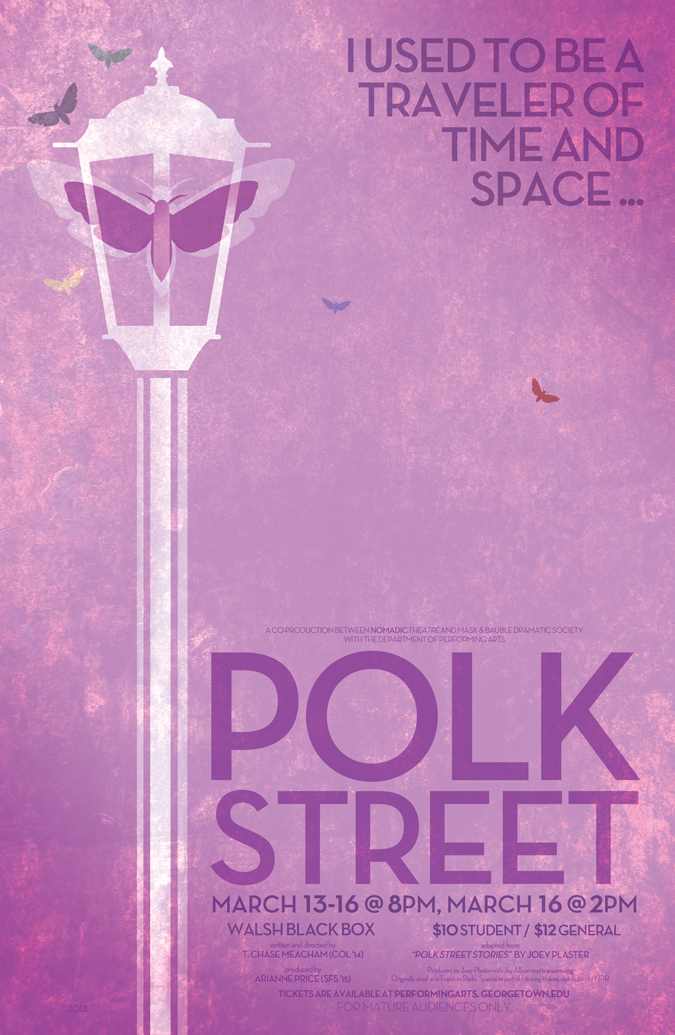

A few years later I got the opportunity to write and direct a play at Georgetown University. I wrote to Plaster to ask permission to adapt “Polk Street Stories” into a play, which happily, he agreed to.

I offered him oversight of the script, which he declined. This was my play, he told me. However I proceed was my decision.

I was at once thrilled and anxious, and suddenly aware of the pitfalls. So many pitfalls! I was about to embark on telling the story of a place in which I’d never lived, or even visited. I was about to tell a story inspired by real people, whom I’d never met.

I had gotten permission from the historian, but not from his subjects. Did they even know? Would they care? Would they give permission? Their stories had been theirs to tell for the oral history project. What about for my play?

More gravely, what right had I to tell a story defined by such suffering? I felt a kinship with this place by virtue of being a gay person. I felt that I had distant roots here, connected by a history I had recently inherited. But other than that I had almost nothing in common with the residents of Polk Street.

I had never run away from home. I had never been abandoned by my family. I had never lost a lover; I had never transitioned; I had never been homeless; I had never sold myself for sex.

In lieu of personal experience I searched for a deep respect for the material as I wrote my play. Some of the characters in my story, which was titled, simply, Polk Street, were representations of characters from the tapes. Others were composites; others were new creations inspired by the voices.

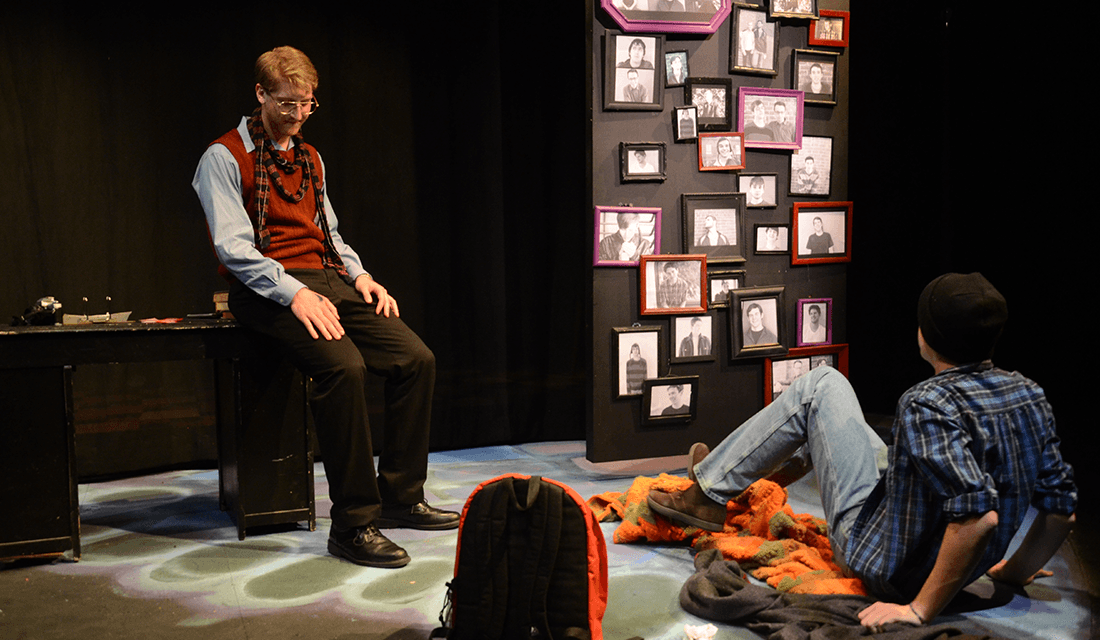

Jason Gusdorf and Nicholas Phalen in Polk Street | Photo by Shannon Walsh, courtesy of the author

I was about to embark on telling the story of a place in which I’d never lived, or even visited. I was about to tell a story inspired by real people, whom I’d never met.

Polk Street itself became a central character. Its struggle with gentrification was embodied by a dive drag bar (the Deja Vu) struggling to stay open amidst attractive offers from prospective developers. Its characters had found a home in an unlikely place, and found themselves fighting for its future against the same steep odds they’d faced their whole lives.

A street lamp anchored the set — inspired by the Godot tree — anchoring the staging in the reality and the banality of a city block clear across the country.

Photo courtesy of the author

In creating the environment, I wanted the audience to feel as though they were connected to this place as well. We held our will call at the conventional entrance to the theater, but then routed audience members back outside, instructing them to head around the building to enter through the back. Along the way they passed boarded up windows, covered in graffiti and advertisements for the Deja Vu.

Actors in plain clothes greeted them along the way. One actor, playing a reverend whose ministry was rooted in love and practical advice, handed audience members programs and condoms as they entered the space.

Another, playing a particularly tragic character suffering from mental illness, was positioned on the sidewalk, enacting loneliness to those who passed him by.

These choices had been designed to expand the world of the play beyond the theater walls, such that the stories of Polk Street might spill onto our street, engaging audience members unaware that they were audience members.

To my delight, one of the people interviewed for “Polk Street Stories” saw the play, and participated in a discussion afterward about the things she had seen, the people she had known, and the lives she recognized in the retelling on our stage.

What happens to the stories of the community when longtime residents are forced to scatter, leaving newcomers in their wake with new stories of their own?

Nicholas Phalen and Jack Schmitt in Polk Street | Photo by Shannon Walsh, courtesy of the author

It’s been seven years since we staged Polk Street. Ironically, the theater that housed the play has since been gutted and renovated and turned into something else.

Fitting, perhaps, for a play about the fragility of history and the transience of place.

The thing that struck me most about “Polk Street Stories” was just how quickly a place can be erased. What happens to the ones who found home there; what of the lives that thrived there, or died there? What happens to the stories of the community when longtime residents are forced to scatter, leaving newcomers in their wake with new stories of their own?

The roots are shallow in places like these, and vulnerability is high. On Polk Street I found the story of a community that was stunningly beautiful, and barely holding on. In “Polk Street Stories,” I found a narrative that celebrates and fights to preserve a piece of history foundational to the LGBTQ story. In Polk Street, I found a bit of me.

A few months after the play, I visited Polk Street with my parents. We visited a bar called Diva’s that had inspired the Deja Vu. We talked with the bartender about the play. We visited a club called The Chapel, and had a drink in the choir loft. It was Disney villains theme night.

The neighborhood was nice. Bright. Beset by homelessness, so chronic in San Francisco, but very clearly turned over from the neighborhood described in “Polk Street Stories.” I wondered how many of the people I’d heard in the tapes still lived there, or anywhere. I wonder where they are now. I wonder if they’re all right.

I think adapting the story of a place makes you part of it. It becomes like a distant relative you try to keep up with. They going their own way, and you going yours. Bound by shared roots and familiar stories; separated by distance; each propelled relentlessly by time.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bu8R8vZh6Ow/