NICK JONCZAK

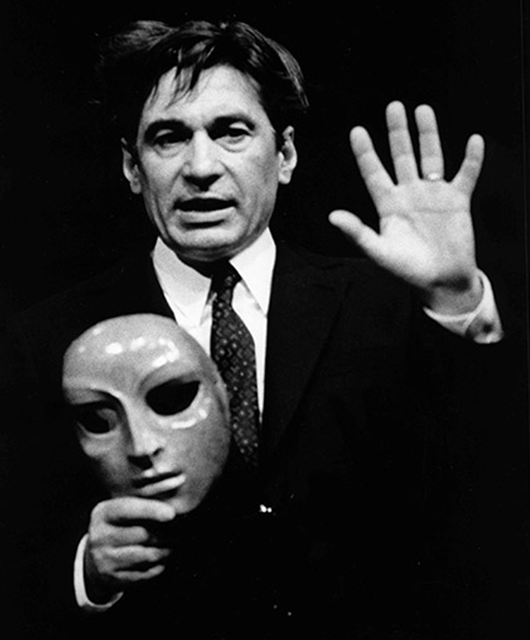

Jacques Lecoq | Source: © Télérama

It is a gift to be present.

Three years ago I uprooted myself from Washington, D.C. where I had spent seven incredibly formative years of my life and moved to Philadelphia to join the Pig Iron School for Advanced Performance Training, a two-year Lecoq-based graduate acting program focused on ensemble-generated devised performance.

TL;DR I went to clown school.

The training is rigorous and focuses greatly on the proximity of performer to audience. Though not all performances are created in the style of clown or performed immediately close to the audience, the work that comes out of the program is dedicated to presence. That is, for the performer to be present with the audience.

Often audiences come to the theater to be entertained. While this may fly in the face of some artists seeking instead some collective effervescence — though the two are not mutually exclusive — it is nevertheless important to remember that audiences first and foremost come to be entertained. They’re here in the theater, expectant, poised for a laugh or a touching moment — open; present. The impossible task of the performer is to be as present as the audience.

To do this, the performer must develop a curiosity about the audience and a sensitivity to their reception of the performer’s act. Even if the performer is not directly addressing the audience, there is a permeability between audience and performer that is necessary to presence. And it is this permeability, this exchange between audience and performer — right now, in this time, in this space, acting this thing with you watching me and me watching you — that the theater is alive. This is the gift we give to our audience and ourselves.

In my two years at Pig Iron I came to realize what I hadn’t understood before: that this sensitivity to and curiosity for the audience is the foundation of theatre as a form of activism.

Historically and at present, there are many examples of plays, performance styles, methods of research, and et cetera, that use as its basis for content some social/political issue. Just see New Freedom Theatre’s recent production of Don’t Bother Me, I Can’t Cope, which adapted the scripted play’s setting to protest the demolition of a local public high school by Temple University, which turned the razed land into a sports field.

For our purposes, I’ll loosely define theatre activism as performance for positive social change, and add that there are many different (sometimes competing) definitions, applications, and outcomes to this term. Perhaps it’s also best to assume that anyone reading this believes positive social change is a good thing.

Agency is the Cornerstone of Presence

The impossible task of the performer is to be as present as the audience.

In middle school, I once read about the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) hiring actors to portray spies and foreign agents in training simulations for American agents. As a young actor at the time, I fell in love with this alternative form of performance. Years later, in college, I performed similar work training Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents in simulated one-on-one interviews wherein I played kids ranging from 5 to 15 years old. These characters (based on real cases) were all victims of sexual abuse and these agents were learning to prepare these children for trial testimony.

In these one-on-one interviews, the line between performer and audience is blurred. The interviewer may ask questions of the victim or vice-versa, and the interviewer comes to the encounter with an understanding that they will be expected to actively participate in the performance of improvised simulation.

These simulations are highly performative and very intimate — usually, it’s just one actor and one agent in a small interview room, with a video camera broadcasting the encounter to a separate room, where trainers and fellow classmates are watching and evaluating the student’s progress in conducting the interview.

It was an incredibly dark but very rewarding work. One time after an agent, Carla, interviewed me (as Jack, a 15-year old boy), she told me how moved she was by the experience because she had a 15-year old son herself. She told me she realized she needed to fight as hard for Jack as she would want another agent to fight for her own son.

By investing in the experience — by choosing to play an active role in the simulation — Carla brought her full attention to the room through the real-life association between me and her son, much in the same way actors trained in psychological realism base their performances in memories of people, places, or experiences from their own lives. Carla had the principle role to play in our encounter, even though I was the actor.

This sensitivity to and curiosity for the audience is the foundation of theatre as a form of activism.

For the purposes of these encounters, agents don’t expect to be entertained as an audience in a theater might, but they do expect a verisimilitudinous experience that immerses them completely. They bring their full presence to the encounter, waiting, as the seated audience in the hushed theater does for the a-ha moment. The one-on-one performance is entertaining not because it makes the interviewer laugh, but because it makes them feel powerful. They have the ability to immediately improve the lived experience of the (simulated) victim before them by consoling them, encouraging them, or just listening.

Each of the agents who interviewed us might interview 1,000 children over the course of their career, and in the short time I performed these simulations, I saw perhaps 60 different agents. It’s staggering to think of the number of children who become victims of sexual abuse every year, but it’s encouraging to know that actors, performers, and artists have a role in improving the quality of care and dignity these children receive when working with agents to bring their perpetrators to justice.

While this is certainly not the only way performance can directly improve the lives of people living in our communities, the greatest strength of these encounters is in structuring the experience so as to give agency to the interviewer to bring their full presence to the exchange. The encounter “casts” the interviewer in a position of power and it is exactly this clarity of casting that helps build the foundation for theatre as a form of activism — in this case, in the name of justice.

Integration is the Cornerstone of Agency

Back in the theatre, all performance is political. Not in the sense that it references a candidate for public office, advances a specific party’s platform, or protests an event (like Don’t Bother Me) necessarily, but in the sense that every word or action in a performance of any kind where an audience has intentionally gathered is expressive of and reinforces a system of beliefs about the world. It is inevitable. The work you make is borne of the work you value.

And so, as its primary political act, the performance “casts” the audience. Often this casting is oppressive and affords little agency to the audience, who — I’ll remind you — is here of their own volition (assuming it’s not their friend’s play) and seeking entertainment. Agency, remember, is to be an active participant; to share permeability between performer and audience.

Performances for one person, five people, or 1,000 people at a time all have the same ability to cast the audience in an encounter that integrates them into the unfolding of the experience.

These days, many contemporary experimental theatre artists are trying to change this political relationship and I’d like to offer up a few working definitions about casting the audience, as I’ve interpreted and internalized them over the years from working with other artists in this field.

Audience separation is the most common form of performance. Walk into any major regional theater in this country and your role will come back to you with great ease — you’re the passive recipient of some neatly-packaged scripted play and you offer quiet reverence as you sit still in your fixed seat for two hours.

Audience participation is usually a one-way street. An actor on stage invites someone in the audience to speak, move, or act in some way, and this act does not influence the play at all (though it may appear to, it’s just an illusion, and this is key). The performance continues on with or without the audience members’ input. For example, during the song “Over the Moon,” Maureen in Rent asks the audience to moo like a cow. They do or they don’t, but the song continues and the narrative of the play is unaffected by the audience’s participation.

Audience integration occurs when the performance necessitates the active involvement of the audience for the narrative/event/experience to progress. For example, in The Post Show, created by The Berserker Residents, the audience arrives at the theater to find the show they expected to see has ended and they’re now engaged in a talkback about a play they have not seen. The performers query the audience for their favorite moments and in response to these false memories (this active input) the performers pretend to lead a talkback about a play that they and the audience are creating together on the spot through fake collective memories.

A scene unfolds as audience members — wearing masks — watches on in Sleep No More | Source: © Forbes

Outside of the theatre community, the hyper-immersive performance installation Sleep No More is perhaps the most salient example of integrating the audience with the performers. Sleep No More and performance pieces like it use ‘complete immersion’ to integrate the audience with the performers. By placing the audience in the same physical playing space as the performers and giving them permission to move about the space at their own pace, the audience is allowed to curate their own experience going from one room to another, choosing to ignore or follow a performer, for example.

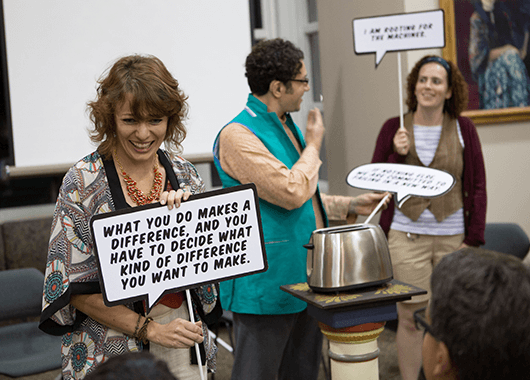

Toast, an audience-integrated show by dog & pony dc, where audience members are invited to participate as part of a ‘secret society of inventors’ | Source: © dog and pony dc

By contrast, companies like The Berserker Residents and dog & pony dc use a method of ‘collective imagining’ to integrate the audience into the encounter with the performers. Their performance works rely little on high production value or deep immersion, and are instead built on engaging the audience in direct conversation, such that their input directly contributes to the unfolding of the performance.

Both complete immersion and collective imagining afford the audience agency to engage the performance as they see fit and, in so doing, develop a deep sense of presence between themselves and the performers.

Intention Elevates Integration

Though all performance is political, not all performance is activism. Activism requires the intent to use the platform of performance to advance a set of political goals; at least, this is what I’ve found to be true in the work I’ve seen and made.

Performances for one person, five people, or 1,000 people at a time all have the same ability to cast the audience in an encounter that integrates them into the unfolding of the experience. The purpose of this integration is to give the audience power, but the question remains of what to ask the audience to do with this power.

It is not enough to simply integrate our performances with an audience, we have a responsibility to show them how to use their power as well.

I’ve heard many artists say — and I have said myself — that they would prefer their art ask questions rather than make statements. But why?

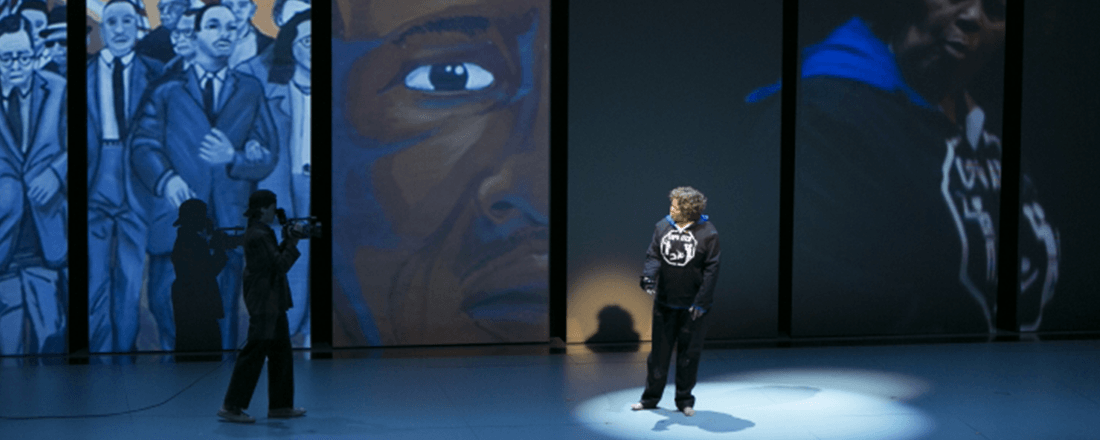

A.R.T.’s production of Notes from a Field: Doing Time in Education, a one-woman show created, directed, and performed by Anna Deavere Smith, which explores the “the civil rights crisis currently erupting at the intersection between America’s education system and its mass incarceration epidemic” | Source: © American Repertory Theater

We expect journalists to research important issues and present their findings as facts. We expect them to help us understand how to interpret the effect of policies, people, and events. Don’t artists share the same responsibility to present to audiences the findings of our artistic research?

If every performance is a political act that reflects and reinforces values about its audience and the communities we live in, then we have a responsibility to develop performances that fiercely advocate for the sharpest, most uplifting values that we uncover in our artistic research. We have a responsibility to show audiences the greatest versions of themselves.

We have a responsibility to Carla and Jack.