EVAN MOUSSEAU

“While we love a good story, we are not always happy with it just being a story. We want to give it a sense of reality. There is no better way to authenticate or codify a story than with the creation of a map. The real question is: how objective can a mapper be when the subject itself is subjective? It is an exercise that is revealing of the artist, the storyteller, and the story itself as the story is translated from the medium to medium. In the harsh light of the mapper’s objectivity the map is often revealed for what it is: a subjective piece of art all its own.”

– Andrew DeGraff

I recently learned that when I was in elementary school, my grandfather would not ask me for directions when he drove places in and around my hometown. In those pre-GPS days of the 1990’s, he relied instead on other passengers for guidance, a task that fell, when he was babysitting us, to my younger sister. When my mother told me this, she revealed it with a tone that clearly implied that this was embarrassing. I had failed to build a mental map of my surroundings.

This came to light in a wider conversation about my ability to read while traveling. Immune to the carsickness that would strike other members of the family, the first thing I was sure to do on my way to the car, no matter how short the drive, was grab my book. As a result, while I had failed to develop any practical “turn left ahead” map of street names and addresses, I had developed a vast array of points in a literary topography: the grocery store where Brian Jacques‘ Mossflower country first shimmered gently in a peaceful haze; the garden center where Harry Potter first confronted Voldemort; the long-closed Bradlees department store where, barely out of Eden, I metaphorically shelved my plans to read my Bible cover-to-cover.

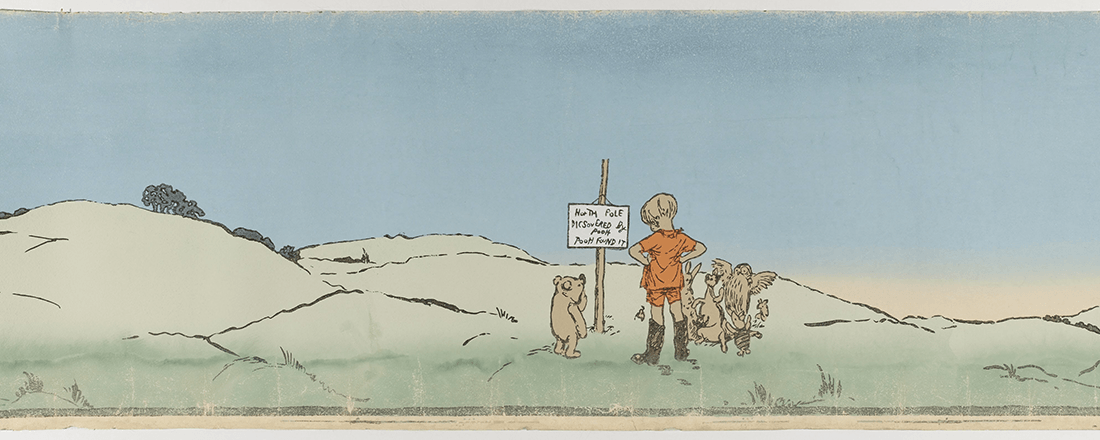

While plotting my fictions on a real map, I was also collecting maps of fictional words. I gravitated toward books in which maps spanned the endpapers or nestled between the table of contents and the story itself. I could wander purposefully through all hundred acres of Pooh’s woods, navigate from Redwall Abbey to Salamandastron, or offer a route from Hobbiton to the Lonely Mountain.

Illustration by E.H. Shepard titled “Christopher Robin Leads an Expotition to the North Pole” from Chapter 8 of Winnie the Pooh | Source: Google Art Institute

In his essay “The Wilderness of Childhood,” Michael Chabon argues that these tales of adventure are dependent on their maps:

“Every story of adventure is in part the story of a landscape, of the interrelationship between human beings (or Hobbits, as the case may be) and topography. Every adventure story is conceivable only with reference to the particular set of geographical features that in each case sets the course, literally, of the tale.”

But his explanation does not end at the level of story-telling practicality. Chabon goes on to suggest, “People read stories of adventure-and write them-because they have themselves been adventurers. Childhood is, or has been, or ought to be, the great original adventure.”

“Childhood,” Chabon writes, “is a branch of cartography.”

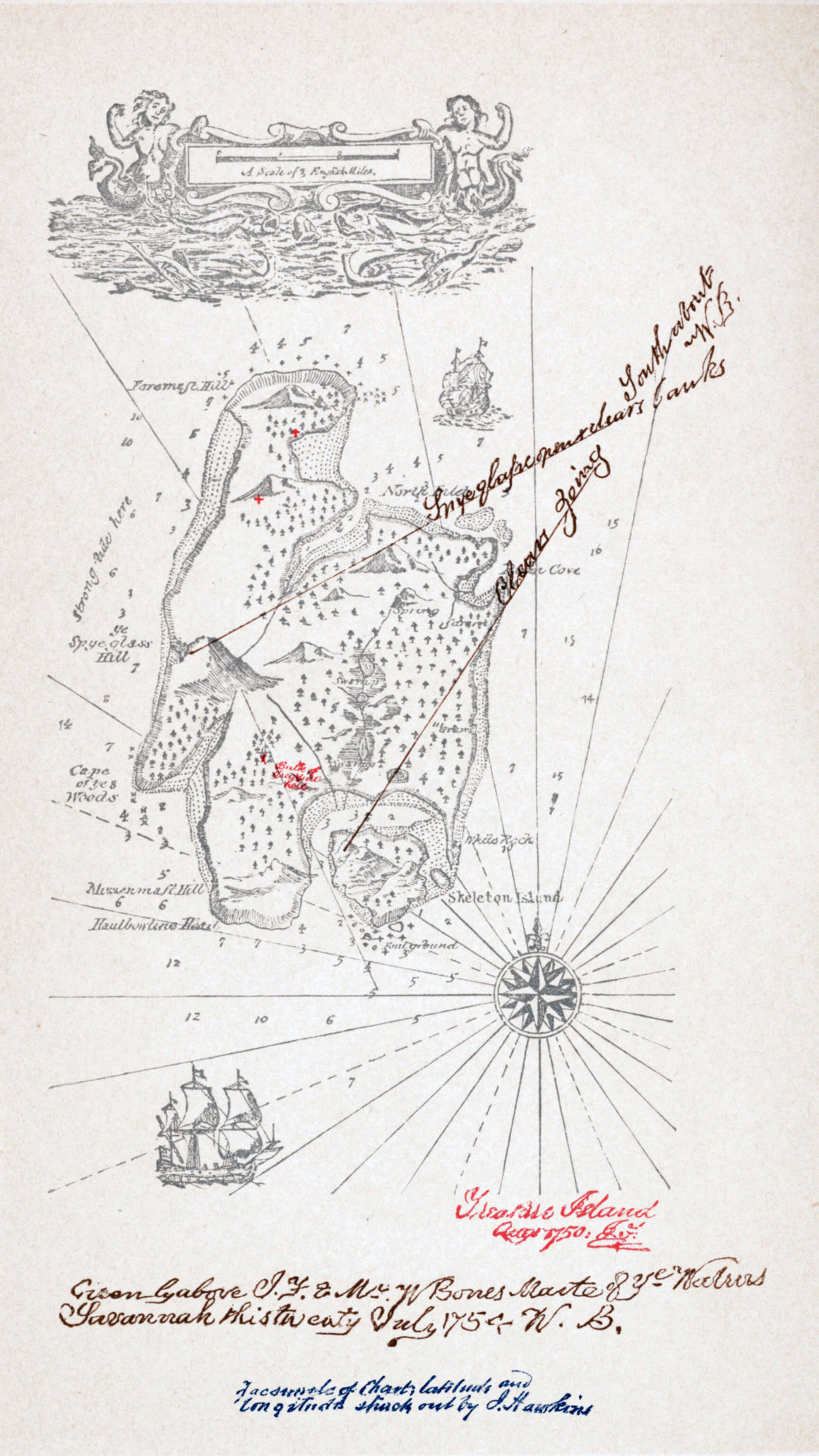

Robert Louis Stevenson’s map of Treasure Island | Source: Wikipedia

In second grade, I made my first map of a real place. My elementary school playground featured classic elements — swings, monkey bars, climbing ropes — though its real highlights were the two-headed tire dragon, the castle, and, anachronistic to its medieval theme, what we understood to be a wooden replica of a grounded airplane. These landmarks were the waypoints on a treasure map I crafted for my reading buddy, a first-grader who would follow my step-by-step directions — quite literally step-by-step, the directions were measured in paces, as if we were striding toward gold on Treasure Island — to a prize of candy and cheap toys sealed in a Ziploc bag.

While we were no doubt supposed to use the real maps we had seen in the unit as a guide, I turned toward my fiction, instead. After all, it was only fiction that gave me the mapping skills I needed to account for the iconic elements of that playground… Here, there be dragons.

Those stories that offer the reader an escape from their daily life, a break from day-to-day ennui or stress.

The first chapter book I read on my own was an adventure story that introduced me to many of the genre elements that would feature prominently in the stories of my childhood: a young runaway, talking animals, a dragon, and, of course, a map. In My Father’s Dragon, by Ruth Stiles Gannett, Elmer Elevator, the narrator’s father, learns from a talking cat of a dragon imprisoned on Wild Island, running away from home with a haphazardly packed bag of survival necessities including, among other things, chewing gum, two dozen pink lollipops, a bag of rubber bands, seven hair ribbons. These items all come in handy as he treks across the unknown territory of Wild Island, taming tigers with chewing gum, appeasing a lion by brushing its unruly mane and adorning it with hair ribbons, and crossing a river by crafting a bridge out of sweet-craving crocodiles, fastening lollipops to their tails with rubber bands.

I read and re-read this adventure, and when I didn’t have time to read, I would flip to the endpapers and trace Elmer’s path on the map of Tangerina and Wild Island. Of great interest to me was the area left unexplored in Elmer’s adventure, a portion left blank, save for the words “my father doesn’t know what’s on this side of the island.” I was left to imagine what untold adventures might await one who explored beyond the story.

This is one of the great joys of stories with maps. They contain the promise of a wide, often idyllic world to populate with your own journies when the characters have concluded theirs.

Map of the islands of Tangerina and Wild Island | Source: Boston Public Library

As he continues to explore the hallmarks of our childhood stories, Chabon goes on to note:

“A striking feature of literature for children is the number of stories, many of them classics of the genre, that feature the adventures of a child, more often a group of children, acting in a world where adults, particularly parents, are completely or effectively out of the picture.”

This is, of course, as much of a genre necessity as the maps. No responsible parent is going to allow their child to search for dragons, save kingdoms, or engage in otherwise dangerous adventures with no adult guidance. But it also works to provide young characters a level of independence that many young readers find incredibly appealing.

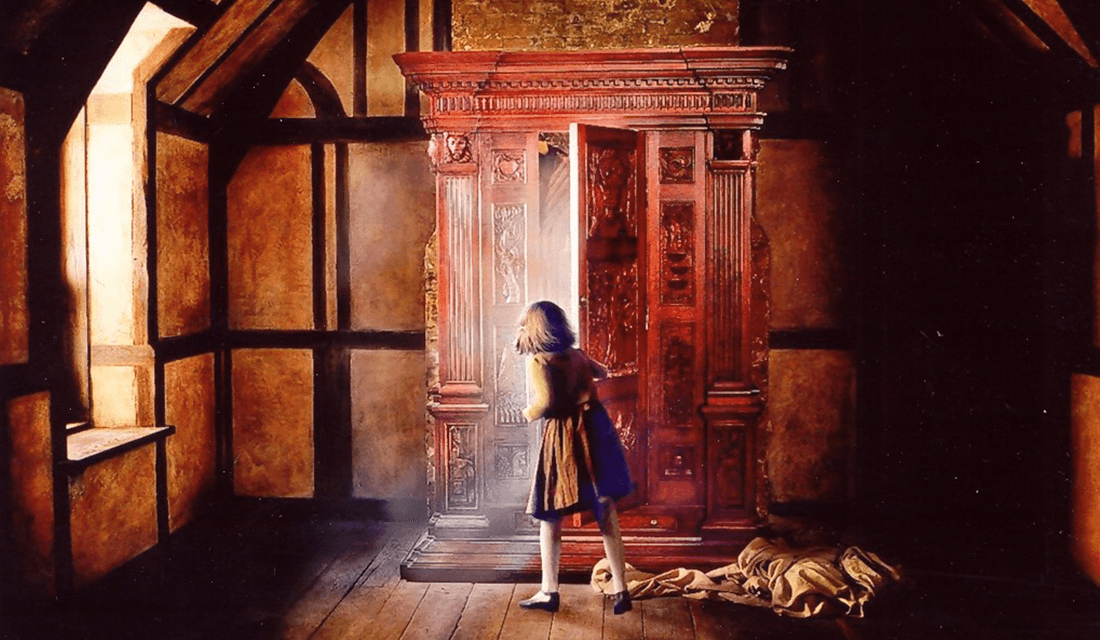

To open a book and be, for a while, away from the trials of daily life is, for many young readers, an escape as glorious as Lucy Pevensie stepping through the wardrobe.

When Gertrude Chandler Warner published the first book in The Boxcar Children series in 1924, in which four young orphaned children live on their own in an abandoned train car, she recalls there being a “storm of protest from librarians, who thought the children were having too good a time without any parental control!” Warner replied that it was exactly this that children enjoyed about the book.

To their credit, my parents did not share the concerns of 1920s librarians. From an early age, books served as a parental surrogate, a tool to occupy me in the early morning before my parents were awake. My mother, frustrated by my tendency to wake up extremely early and cry, found that books could grant her an extra hour of sleep. She began placing a pile of books at the foot of my crib, providing me with an early morning distraction as I turned pages and babbled happily to myself.

Eventually, I graduated to a big-boy bed, and the books came with me. My headboard was a bookshelf, and while the stories that filled it were frequently without responsible parents, my own parents were responsible for my reading habits.

The sorts of books that open with maps generally fall into those areas of genre fiction described, not without a slight tinge of academic contempt, as “escapist fiction.” Those stories that offer the reader an escape from their daily life, a break from day-to-day ennui or stress.

For the children whose own situations mirror those of the protagonists of these escapist texts, the relief offered by such a break is clear. One can easily imagine the psychological succor that Harry Potter‘s promise of hope and magic offers a child living in cramped quarters with abusive relatives. To open a book and be, for a while, away from the trials of daily life is, for many young readers, an escape as glorious as Lucy Pevensie stepping through the wardrobe.

But for those who, like this author, grew up in a position of privilege, with loving parents paying for these books so often devoid of loving parents, whence the escape?

Lucy Pevensie Entering the Wardrobe, into Narnia | Source: WikiNarnia

Though the main character of My Father’s Dragon is the narrator’s father Elmer, he exists in the story as a young boy, still a long ways away from having a child who will recount his tales. Elmer runs away from home after his mother refuses to entertain his desire to care for the talking stray cat, whipping her son before throwing the cat out the door. When I imagined myself in Elmer’s shoes, I focused on the adventure itself, ignoring the inciting events.

Similarly, when we turned the wooden cabin of the playground airplane into a train car to play as the Boxcar Children, I chose to think of us as young and independent rather than orphaned.

The explorations of these fictional lands were always tempered by a selective imagination, one that would have placed the Pevensies’ wardrobe gateway to Narnia not in a blitz-threatened England far from their parents, but squarely in the safety of a loving family’s home.

For the children whose own situations mirror those of the protagonists of these escapist texts, the relief offered by such a break is clear.

Chabon’s essay goes on to examine what he sees as a rapidly vanishing level of wilderness in the real lives of children today. Gone, he laments, are those unmapped spaces where children are allowed to roam independently for hours at a time, “abandoned in favor of a system of reservations — Chuck E. Cheese, the Jungle, the Discovery Zone: jolly internment centers mapped and planned by adults with no blank spots aside from doors marked staff only.”

He wonders as a father about whether he can or should send his children off into the world around them to explore, all the while contrasting the dangers of the modern world with the idyllic freedom and exploration of his own childhood, as when he bicycles around his neighborhood with his daughter in “that after-dinner hour that had once represented the peak moment, the magic hour of [his] own childhood,” but does not come across a single other child.

The kids, and indeed the institution of childhood, Chabon seems to be arguing, are not alright.

The map I once made of my elementary school playground is lost to time, in spite of my mother’s archivist tendencies. Likely it went home with its first-grade treasure-seeker, rather than the creator.

No matter, it would be useless now, a map to a place that no longer exists. That playground is a field now, and the school has built a new one. The splintery wood of the castle, the metal slides that would bake in the sun, the tires that made both the body of the dragon and perfect hiding spots for bees’ nests… all gone. The new playground, plastic and sterile, is nowhere near as dangerous as the one I mapped all those years ago. And, I am sure, nowhere near as fun.

Chabon’s first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, ends its narrator’s recollections of an eventful summer by declaring: “No doubt all of this is not true remembrance but the ruinous work of nostalgia, which obliterates the past, and no doubt, as usual, I have exaggerated everything.”

[These maps and books] bring me back to the place where those stories were once shelved, the base from which each adventure began, the place to which I could return when the adventure was over.

To say that the utopias of childhood are those places, real and imagined, that exist beyond the bounds of adult influence is, I think, to miss the point. The maps I followed as a young reader, those maps that I laid over my real world through reading in my parents’ minivan, my schoolbus, my grandfather’s car, were not maps of true escape, but maps of brief recess.

Those places on my childhood maps of which I might say, “my father (or mother!) doesn’t know what’s on this side of the island,” do not work alone to create my fond memories. It is the wider context in which these places existed that gives them value, my knowledge that, while I could sneak off into worlds outside of adult control, in my books and my playtime, I could return to the comfort and care of a world maintained by grown-ups when my adventure grew too perilous.

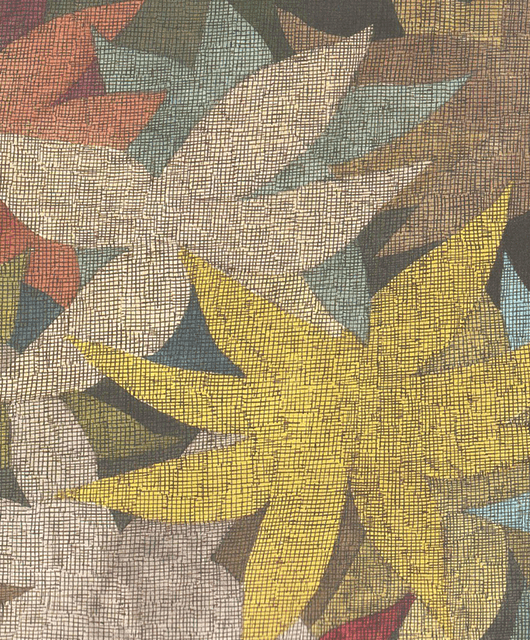

The floral endpaper pattern of Where the Wild Things Are | Source: Weheartendpaper

There is no map in the beginning of Maurice Sendak‘s Where the Wild Things Are. The endpapers are instead illustrated with brightly colored flora. And yet this book may offer the best illustration of the wilderness of my childhood. When Max, having made mischief of one kind and another, sails away from his home to the land Where the Wild Things Are, he enjoys an adventure far outside the world of parental influence. When he grows lonely, though, and tires of his adventure, he sails “back into the night of his very own room where he [finds] his supper waiting for him… still hot.”

Max’s return to that “place where someone loved him best of all” is a return to a place I will not find marked on the maps of my childhood stories. Still, when I look at these maps or open these books again, they offer a navigation back to that place. They bring me back to the place where those stories were once shelved, the base from which each adventure began, the place to which I could return when the adventure was over.