NORA ROSENGARTEN

10,000 – 8,000 B.C.E.

European Cro-Magnon Hunters draw the shape of the symbolic heart. The exact significance remains unknown.

A Cro-Magnon pictogram from before the last Ice Age | Source: © Paul Silverzweig/PBS

It was a strange coincidence that on the day I was asked to write for SixByEight Press on the etymology of the heart symbol (♥), my class began learning about the Circulatory System. I’m a preschool teacher. My students are between three and six years old — and they are obsessed with learning about their bodies. Every year, we begin with the basics: the Skeletal, Digestive, and Muscular Systems, and progress into the increasingly less tangible Circulatory, Nervous, and Immune Systems.

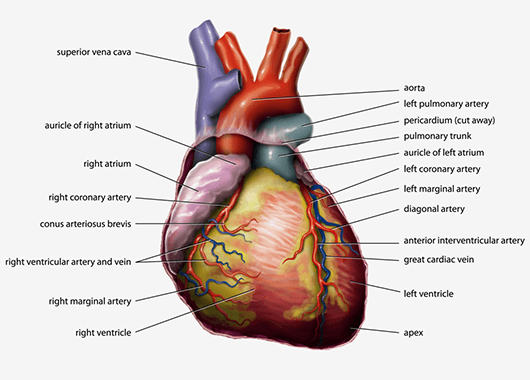

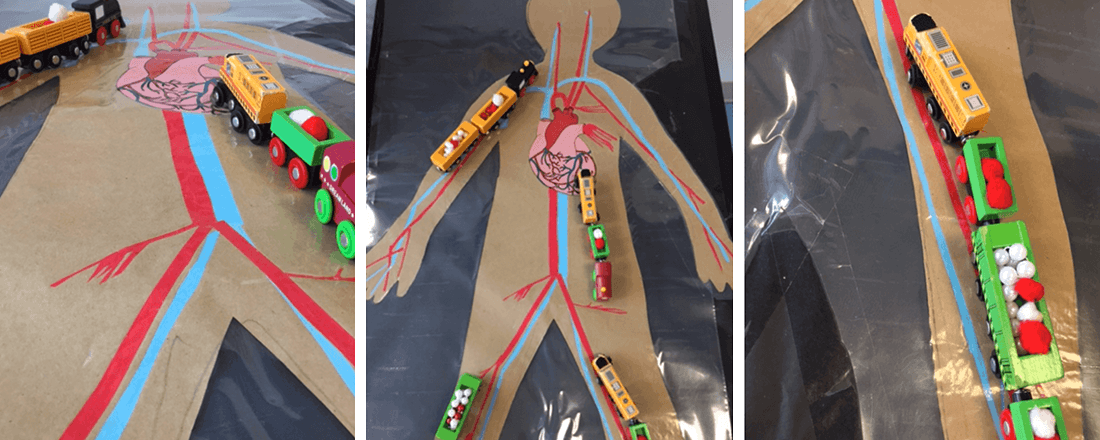

For a whole week every year we learn about blood, white and red blood cells, veins and arteries, and the heart’s four chambers. We use the metaphor of a train, carrying oxygen and energy to each of the body’s extremities. We even act out the cycle as a whole class, tip-toeing along red and blue lines of tape across the floor, crawling through tunnels arranged to simulate ventricles, to the sound of rhythmic thump thumps through the classroom speakers.

All my students know where their hearts are, and that they have a heart. We often talk about our hearts beating in the context of calming down. We feel our pulses as a class to talk about how we feel when we are upset or when we are sad or when we are mad. I teach my students breathing and meditation exercises to calm down if they are feeling upset.

There are two primary reasons that kids love to learn about their bodies. The first, obvious explanation is that the topic taps into their natural curiosity. How and why do we run, eat, get sick, sleep? To a three-year-old, these questions are persistent and only encouraged by adults’ terse responses. We sleep because we are tired. We eat so we have energy. You’re sick because of germs. To truly answer a five-year-old who asks, “Why did I get sick?” requires knowledge of multiple body systems, some play with representative toys, and several hours. A few fun nursery rhymes won’t hurt either.

However, I think there is a second reason my students love to learn about their bodies. In fact, I believe this factor encourages their wonderings, emboldening three- or four- or five- year-olds to ask again and again. Their pursuit of information is motivated not only by what they want to know (curiosity) but also by what they already know (knowledge). My students are the experts on their own bodies. They have more experience with their bodies than with any other topic in their lives. On this topic, they get to hold all the cards — to present evidence, weigh the facts, and label their experiences.

Possession of a heart begged the questions: What is this? What does it do? How does it do this? Why does it matter?

In early childhood education, the framework for understanding new information is referred to as the child’s schema. The more context (ideally delivered via direct experience) the student has on a topic, the more that child will be able to connect and extend his or her understanding. In most arenas of life, kids are experiencing things for the first time, sometimes without a schema to support their risk-taking. Two weeks ago, one of my students ate a tomato for the first time! His schema of experience with other vegetables and fruits (a tomato is which, again?) allowed him to take the risk and try a new one. Before biting into the tomato, he asked me if it would taste more like an apple or a strawberry.* This is an example of a kid using his schema to prepare himself for an unknown — and potentially stressful — experience.

[Children] have more experience with their bodies than with any other topic in their lives. On this topic, they get to hold all the cards — to present evidence, weigh the facts, and label their experiences.

Adults tend to romanticize the freshness of a child’s perspective. We have eaten too many tomatoes. Our familiarity is a handicap, restricting us from recalling how absolutely terrifying the unknown can be. Fear is a completely natural reaction, especially in situations where we find ourselves without a supportive schema. It seems one reason my students enjoy the human body unit so much is the plentiful context they bring to the discussion. Such exploration poses less of an intellectual risk than learning about outer space, or a veterinarian’s office.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although my students have some schema for contemplating the existence of a heart, this schema is insufficient preparation for the raw, gory appearance of the anatomical heart.

I remember the first time I taught this unit. I was naïve and unthinking, and curated a PowerPoint presentation riddled with images of the anatomical heart. As I flipped through the slides with each of my seven classes, the reaction was immediate: Ewwwwww what is that it’s disgusting ughhhhh. Across the board, the kids were grossed out. I could not distract them with the heart’s power, its necessity, or the fact that — like that imposter tomato — the heart is actually made of cardiac muscle and, therefore, technically straddles the muscular and circulatory systems. Nope. They gaped and guffawed. No one could concede they might actually have something like that buried deep in their chests. And, if I looked at the anatomical heart through their eyes, I easily shared in their disbelief. The feeling of having a heart does not prepare a person for the physical reality of that heart.

[People] in the past did not understand how the heart works, yet they lived.

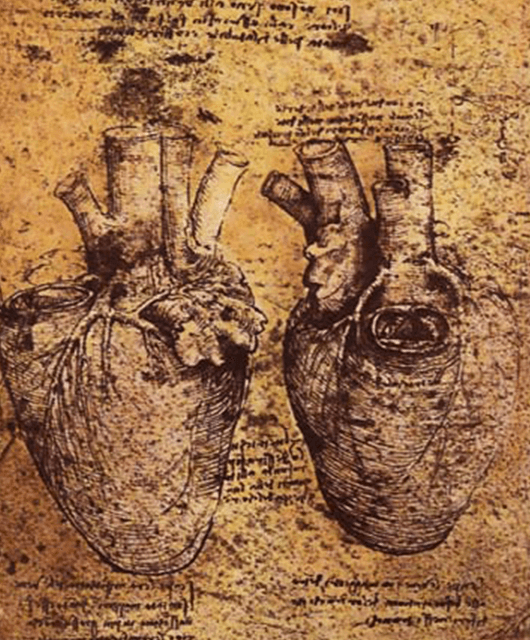

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of a human heart | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Often, at moments like these, I imagine my students’ questions, concerns, and reactions mirror those of people and societies throughout human history who struggled with fundamental questions of existence. Romans, Greeks, Egyptians; nearly every major civilization took a stance on the heart and its relationship to humanity. Like my students, these societies extrapolated from the experience of being a person and having a heart to the conclusion that the heart mattered. Possession of a heart begged the questions: What is this? What does it do? How does it do this? Why does it matter?

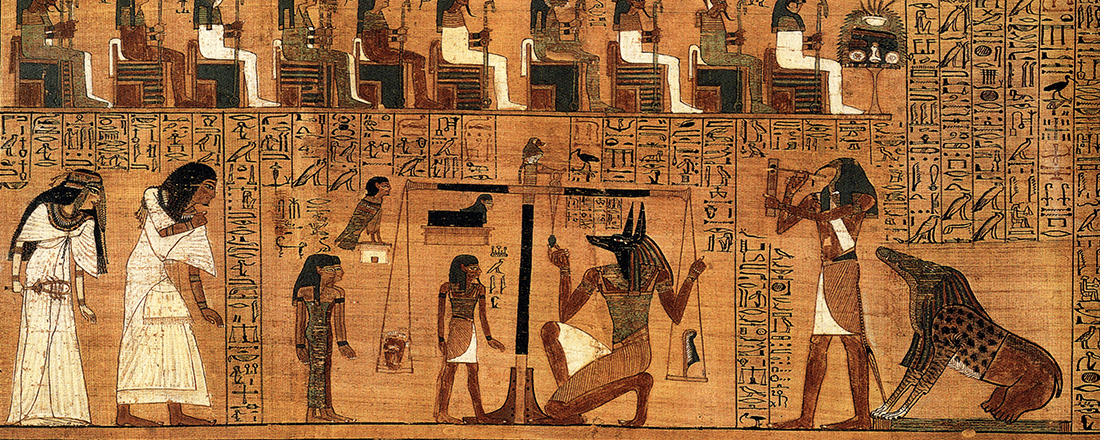

2,500 – 1,000 B.C.E.

Popular Egyptian mythology claims that after death, the heart is transported to the goddess Maat (Justice) who weighs the organ against a feather. Only those with hearts lighter than a feather can join Osiris in the afterlife. If the heart is heavier than a feather, a demon will eat it and the person’s soul will cease to exist.

Weighing the heart (left scale) against Maat’s feather of truth (right scale), to determine the fate of the deceased’s soul | Source: Wikimedia Commons

In an early childhood classroom, learning happens through doing. My job as a teacher is to create an environment and activities that encourage students to take risks and orient themselves with regard to each topic, at times literally and at times figuratively. Here are a few examples of activities I brainstormed, assembled, and presented to my students during our week on the circulatory system.

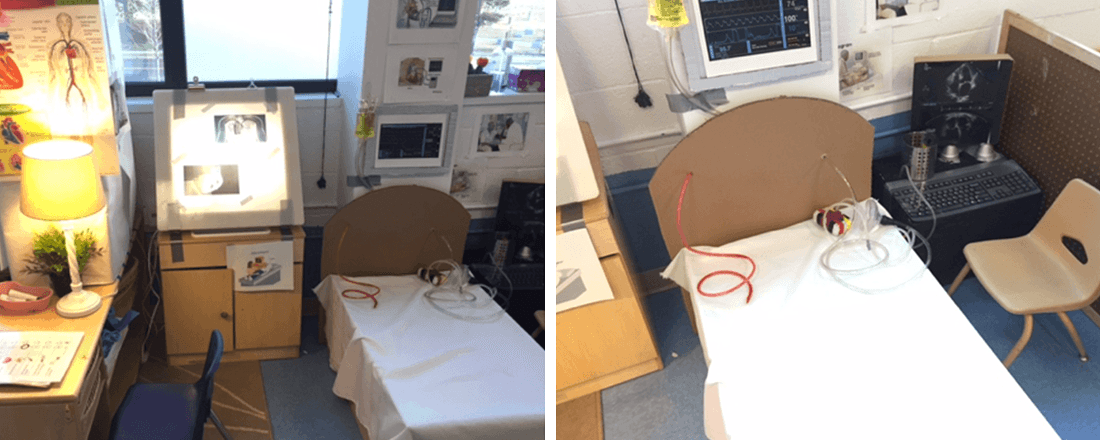

♥ The Cardiologist’s Office ♥

Photos courtesy of the author

The first center I created was a cardiologist’s office, complete with an echocardiogram machine, respiratory support, and a transfusion station. Students have a broad schema for understanding doctors and doctors’ offices, so this concrete expression provided roles and scenarios for exploring heart and blood malfunction.

Also, a waiting room, because you have to keep the patients occupied.

400 – 200 B.C.E.

Ancient Greeks identify the heart as the source of the body’s heat and — maintaining the Egyptians’ stance — the soul’s resting place.

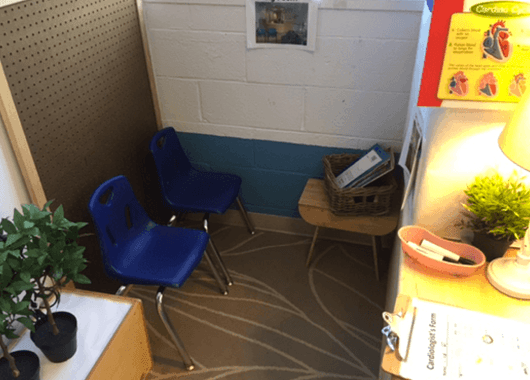

♥ Circulation in Action ♥

Photos courtesy of the author

I created two sensory tables to communicate the components and mechanism of blood movement. These tables communicate principles of circulation through symbolic representation. Students are encouraged to see themselves as either facilitators or acting as a part of the body (the heart, or the white blood cells, for example). The first uses red and white beads to signify the red and white blood cells. Beads can be strung on wire or pipe cleaners, and then conveyed through clear tubes that mimic the arteries and veins. Four squishy, pump-able hearts allow students to act out the pumping motion propelling the blood components through our bodies.

The second sensory table communicates blood’s liquid form and its paths through the body. Sieves and tunnels and tubes allow students to pour food coloring and water as though they are moving it through the body. In this center, students are the heart itself.

130 – 200 C.E.

Claudius Galenus (Galen) serves as personal physician to Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Galen’s medical discoveries — primarily focused on dissections of animal remains — are the gold standard through the Middle Ages. Galen identifies the heart and its relationship with the lungs, but fails to understand how blood circulates.

♥ Pumping with Pipettes ♥

Photos courtesy of the author

I simulated the heart’s pumping with a painting activity. I took salad spinners adorned with hearts and placed coffee filters inside. Students used pipettes to pour red and blue paint on top of the coffee filters, then closed the tops and spun them by pumping the heart. The paint is pushed out from the center by the force of the salad spinner, creating red and blue tendrils that resemble veins and arteries.

1628

An Anatomical Study of the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals by William Harvey is published. It accurately describes circulation for the first time.

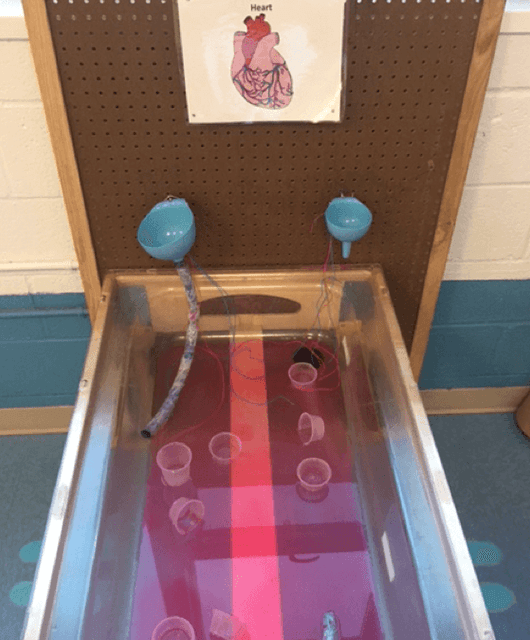

♥ Carriages of Cells ♥

Photos courtesy of the author

To help students visualize blood cells traveling through the body, we used the metaphor of a train. In this center, students loaded train cars full of white and red blood cells, then pushed the train around the body’s outline to carry oxygen to every part of the body. The white and red blood cells then return to the heart to replenish their store of oxygen. Like a train, the blood cells cannot leave their route, which is a complete circle.

1896

“Surgery of the heart has probably reached the limits set by nature to all surgery. No method, no new discovery, can overcome the natural difficulties that attend a wound of the heart,” writes surgeon Stephen Paget.

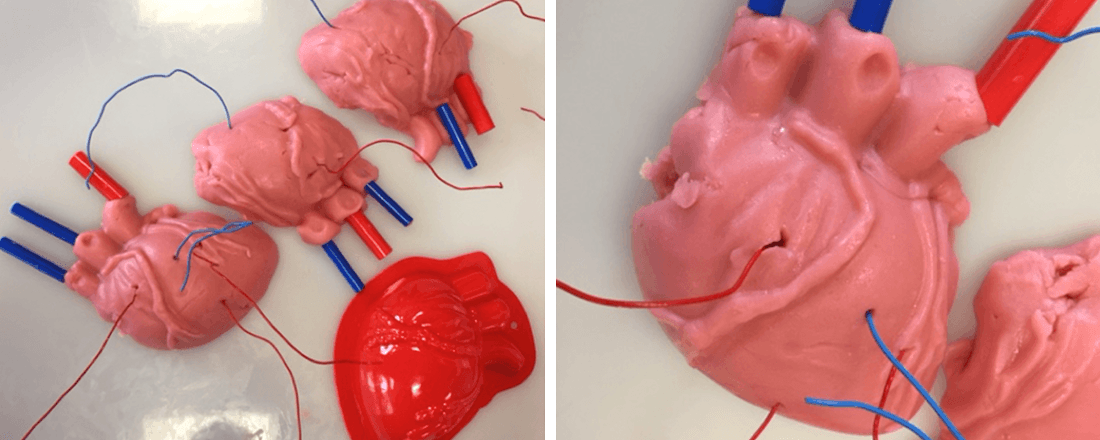

♥ Opening the Heart ♥

Prompted by the doctor’s office, we discuss open-heart surgery. Using anatomical heart molds, students were able to create and then perform open heart surgery on Play-Doh hearts. The marker caps make for perfect right and left ventricles, and the wire pieces are veins and arteries branching out from the heart.

Photos courtesy of the author

1998

Michael Debakey becomes the first doctor to successfully insert a battery-powered, artificial heart into a patient.

How does my heart beat? Why does it look like that? Where does the blood go? What happens if my heart stops? Can a heart break?

The centers I create provoke many questions. They give my students concrete materials and situations they can refer to and between as they try to understand the mysteries of their bodies. Sometimes, the knowledge can be overwhelming and scary. When my students are afraid, I return to the heart. I tell them it is an involuntary muscle — that it will do its job whether they understand it or not, whether they think about it or not. I remind them that people in the past did not understand how the heart works, yet they lived. I hope explaining this distinction reassures my students that they don’t have to worry about everything. Some things will happen all by themselves. You don’t have to know why or how your heart works. It just does.

Four Hearts by Jim Dine | Source: © Tate

In the end, I did not address the etymology of the heart symbol in human history. There were too many possibilities, so many different historians hoping to perfectly articulate the origin and meaning of two curved lines meeting. Instead, I settled for an exploration of the symbols and metaphors I use to explore the heart with my students. It is easy to substitute a symbol for something complex, messy, and unknown; trace possible etymologies as they meander past Aristotle and Giotto and da Vinci. I don’t want to present my students with a world that is complete, and so I show them their real heart and tell them: it is okay, we can grapple with this together.

* I said strawberry. Afterward, he told me I was completely wrong and it was nothing like a strawberry.