ALEXANDRA REALE

Source: MoMA/Facebook

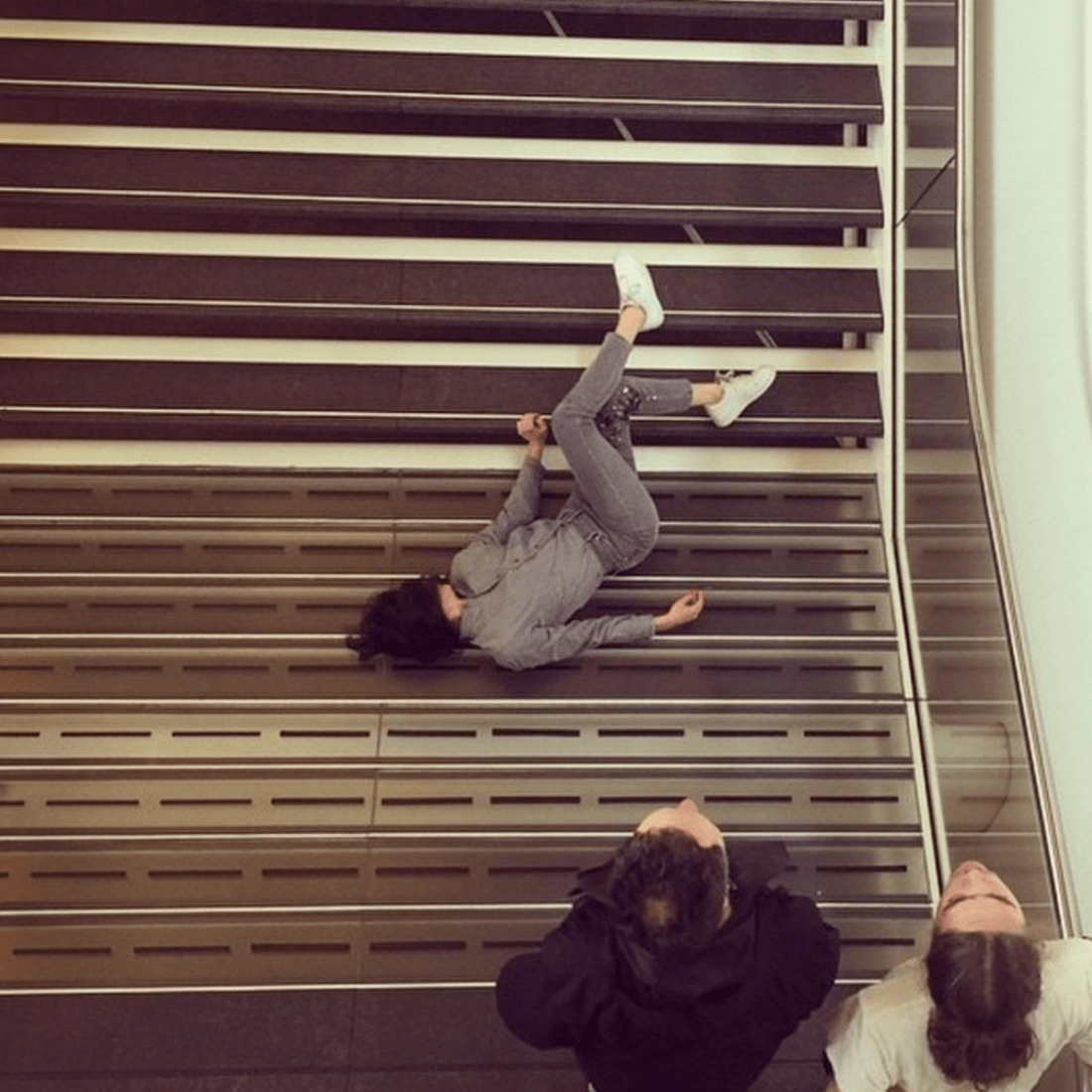

It’s spring in New York City. I’m sitting at the base of the staircase that leads from the first to the second floor in the Museum of Modern Art in Midtown, sweating slightly from a long walk and clutching a notebook and pen. Chattering museumgoers swirl past me, laughing, showing each other messages on their iPhones, buoyant as only warm New Yorkers can be. They have shrugged off their coats, consulted their maps, and readied themselves for the wonders of MoMA. The first floor doesn’t have the exciting stuff; the paintings, the sculptures, the carefully curated and historically formidable works — all that begins on the second floor. They take the stairs two at a time, bounding past me, towards Matisse and Monet. In their haste, they bypass the first piece of art: the dancer on the stairs.

In their defense, she’s easy to miss. She wears pedestrian clothes, is seated at the top of the staircase, and appears to be motionless — a tourist taking a short break in an inconvenient place, perhaps. But her motionlessness is illusory. To take a second look is to discover that every muscle in her body is engaged, and that she is in mobile progress. She perches for only a fraction of a second, and even the seat is a trompe l’oeil. She is moving, changing, never still. A couple of blinks and she has begun a journey down the stairs, not by walking upright, but by making herself prone and rolling down the stairs in slow motion, extending one leg at a time, ever so slowly, ever so carefully.

Maria Hassabi: PLASTIC | ARTIST PROFILES | Source: © MoMA/YouTube

She uses the weight of her outstretched body to keep from tumbling down the staircase, gripping each step like a snake, a sloth, finding only short moments of rest before the steady relentlessness of her downward trajectory inevitably turns her upside down again. She rarely has four limbs attached to the stairs; a slow moving arm or leg turns her off her natural axis time and again as she seeks the safety of the next step down. Her fingertips quiver from the effort of measured slowness, and suddenly they find concrete — the careful landing of a spacecraft on an alien planet. It is brutally slow and difficult, and while sweat beads form on her brow and the muscles in her arms and legs shake from the tension, tourists keep walking by, their shoes nearly treading on her vulnerable hands. After an excruciating hour, the dancer finds herself on the bottom stair, her journey complete. With no change in expression, she stands up, turns, and melts into the crowd.

[The] dancer on the floor, by surrendering her body to the piece, had allowed defined terms of human interactions to grow fuzzy, nebulous.

This was my experience of Maria Hassabi’s PLASTIC, a performance art piece which, through dance, explored themes of motion and stillness, object and audience. Hassabi began with an elegantly simple concept: take seventeen dancers, place them in public, transitional spaces within museums, and have them — slowly and sinuously — move across the spaces. During the month that the exhibition went on, there was never a time during open hours in the MoMA where dancers weren’t continuously moving through the designated spaces in the museum. MoMA’s online description of the piece puts it nicely: “With no apparent beginning and end, PLASTIC reformats the duration of theatrical performance into a month-long museum exhibition.” I witnessed this firsthand: when my dancer finished her journey and joined the crowd, I had barely registered her disappearance when I saw out of the corner of my eye another dancer approaching the top of the stairs. The first law of thermodynamics, rendered by an artist.

Though Hassabi’s piece invites myriad interpretations, I think it is the interaction (or lack thereof) between performer and audience in this shared public space which is most compelling. In removing dance from the proscenium stage, Hassabi invited a reckoning: viewers of her work did not immediately and intuitively understand the rules of engagement. A painting on a wall is simple — stand in front of it, I’m here, it’s there, I watch it, it does not watch me. A dancer stepping where we step engenders a confrontation: suddenly we are amidst what had once been separated by barriers, pedestaled and kept apart. The watched can watch back; borders blur. We will see how the conflation of person and art can cause a peculiar — and dangerous — public reaction, particularly in the realms of dance and performance art.

Hristoula Harakas in Maria Hassabi’s PLASTIC at the Museum of Modern Art | Source: Maria Hassabi/Instagram

Let us sit back down on the floor and watch the dancer on the stairs, and the people in the museum who make up her chorus. There are two security guards who are stationed on the staircase, one at the top and one at the bottom. Their purpose is to keep the dancers safe from errant feet and harm in general. The one at the top repeatedly intones, as people around the corner to take the stairs down, “Stay to the left.” More than once perplexed expressions transition quickly to alarm as people look around for the reason for the instruction, and, discovering the prone person on the stairs, do some rapid mental calculation. Is she hurt? Is she making a scene? Is this part of the exhibition? Most people recover quickly from these internal conflicts, assume a slightly embarrassed and deferential expression, and hurry down the stairs past the dancer without looking at her. Some are concerned about her well-being. They stoop down slightly to get closer to the dancer’s eye level, ask her if she is okay. This is very touching. She does not respond, and often the security guard takes pity on them, briefly explains, and sends them on their way.

PLASTIC at Stedelijk Museum | Source: Maria Hassabi/Instagram

But the most fascinating group are the curious. These ones around the corner, hear “stay to the left,” look down, and their eyes light up. They step closer to the prone person, so that they are right in her personal space, their shoes in line with her eyes. They watch with great concentration the movements of her body, look her up and down as she makes her journey. It is entirely one-sided: consent is presumed by the watcher, and it is the they who dictate the way the interaction will go. The dancer does not answer questions or ask presumptuous watchers to step back (except in special cases; in Siobhan Burke’s piece in the New York Times, Maria Hassabi describes telling one visitor to give her more space — to which he responded, “Why? But you’re art!” — and dancer Hristoula Harakas recalls being poked with a cane while performing PLASTIC in Amsterdam). It seemed that the dancer on the floor, by surrendering her body to the piece, had allowed defined terms of human interactions to grow fuzzy, nebulous. She was a living, breathing human being, but her status as “art” broke down tacit structures of politeness and respect to which we ask members of society adhere. Now she was fair game for voyeurism of the most immediate kind, unprotected by barriers of any sort. Perhaps the people who looked her up and down or made comments about her body’s movements to their friends would not have felt permission to do so had she been a person they met in a coffee shop or sat next to on a bus. This was what made the end of her journey so fascinating. The bottom of the staircase marked a theoretical pivot point: having morphed from human into art as she climbed down, she was alchemized by the last stair and stood up, human once more.

A dancer stepping where we step engenders a confrontation: suddenly we are amidst what had once been separated by barriers, pedestaled and kept apart. The watched can watch back; borders blur.

PLASTIC, at least while I was there, was enjoyed by overwhelmingly polite spectators, who gave the dancers space and did not cause harm. Most of the dark conclusions I drew about human-art interactions came from extending possibilities and exploring theories; I never felt that the dancer was in any real danger. But what would happen if she had, in fact, been in real danger? How do people navigate spaces where they are given permission to disregard laws of respect and politeness? We have lots of examples from psychology — I’m thinking of the Stanford prison experiment and the seizure experiments — and the conclusion the data often indicate is that, given the opportunity, otherwise decent human beings regress to a cruel mean. Power props like sunglasses and uniforms, or authority over another group — even when granted arbitrarily — are enough for human beings to accept and embrace imposed roles, willingly causing harm to others to satisfy external expectations. It is dangerous and sadly inevitable. One artist who understood this unfortunate defect in human nature and explored it in elegant and provocative ways is the fearless Marina Abramović.

Rhythm 10 | Source: Charlie Hung/Blogspot

Abramović is perhaps the foremost performance artist of our time. Born in 1946, she grew up in the politically turbulent former Yugoslavia, a child whose experience of chaos and pain came firsthand. Creative, brilliant, and well acquainted with hardship, she found her calling in dangerous, boundary-pushing performance art. To give you an idea of her style, take one of her early pieces from 1973, entitled Rhythm 10. She explains in her excellent book Walk Through Walls that this piece was based on a Slavic drinking game involving — what else? — knives and alcohol. In Rhythm 10, she kneels on a white sheet of paper in front of a crowd in Melville College in Edinburgh, Scotland (and many times thereafter, in other locations), her left hand on the paper with fingers spread, and in her right hand a knife. With a tape recorder on, she repeatedly stabs the space between her fingers, moving the knife as fast as she can. When she inevitably misses the spaces and hits the sides of her fingers, the tape picks up her sounds of pain. Blood pours onto the paper, and viewers are transfixed. It was this experience, she says, which so infused her with the desire to make dangerous art: “I had felt that my body was without boundaries, limitless; that pain didn’t matter, that nothing mattered at all — and it intoxicated me… That was the moment I knew that I had found my medium.”

Could it be that we, the public, are constantly drawing lines in the sand — human vs. art, us vs. them — and using this as an excuse to manipulate or harm a body?

As she began to make a name for herself, she found an artistic partner and lover in Ulay (he went only by this name), a German artist whose chosen medium was also performance art. Abramović and Ulay traveled all throughout Europe and North America in the 70’s and 80’s, performing pieces such as Rest Energy, where for four minutes Ulay and Abramović held opposite ends of a drawn bow, leaning away from each other so that Ulay drew the arrow against Abramović’s heart. They remained like this, tensed, the entire time. One slip up or moment of fatigue from Ulay would spell grievous injury or death for Abramović. In another piece, titled Relation in Space, they ran naked through a warehouse in Venice, Italy, smacking repeatedly into each other at full speed for almost an hour. They found their concept in collision: “Two bodies repeatedly, pass, touching each other. After gaining a higher speed, they collide.” They bruised and battered each other in dozens of pieces like this. This became Abramović’s brand: an exploration of pain and injury in art, usually over exhausting durations or with self-imposed, difficult rules she required herself to follow.

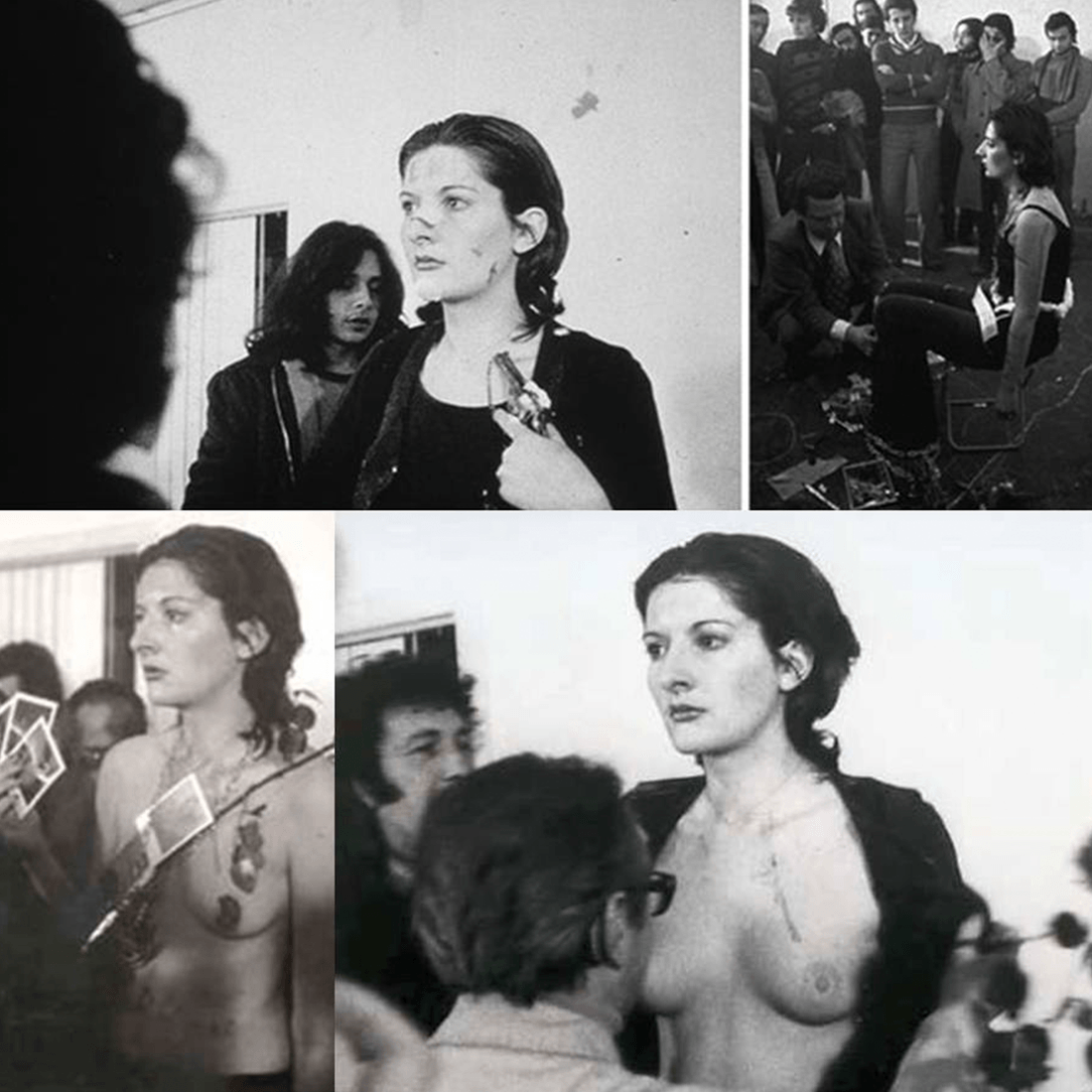

Rhythm 0 | Source: St. Mary’s College of Maryland

Though most of her art involved herself and Ulay as artists and the audience as an audience, with minimal or no interaction between the two groups, there are a couple of notable exceptions. In 1974 she was invited to perform in a studio in Naples, and decided on a work where she would allow the audience to determine the course of the piece. (For a wonderful explanation of this piece, see “The Gospel of What-Ifs According to Marina Abramović”). She called it Rhythm 0. For six hours, she stood in a black shirt and pants next to a table with 72 objects of varying degrees of harm (they ranged from a feather and a mirror to a carving knife and a gun) and invited spectators to use any of the objects on or around her body. She would stand there silently, accepting the treatment without comment. In effect she ceded, totally, power over her own body, granting the audience total rights to manipulate her as they saw fit — the ultimate interaction of public and art. You will be dismayed and not surprised to learn that things quickly devolved. At first, people turned her head to the left or right, made her hold something, or wrote on her, but she was soon de-clothed, carved with the knife so that she bled, and, finally, made to hold the gun to her head, the trigger lightly touched. It was at this point that some people verbally and physically expressed their horror, moving to restrain the person who had handed her the gun, but many stayed silent and unmoving, waiting to see what would happen next. After the six hours were up and she stopped passively receiving whatever manipulations the crowd offered and readied to leave, she experienced something bizarre: “At this moment, the people who were still there suddenly became afraid of me. As I walked toward them, they ran out of the gallery.”

Of course, this is not bizarre. Remember our PLASTIC dancer? She was also subject to this frightful tendency people have to make “fellow human being” and “art” mutually exclusive, albeit to a much less extreme degree. Could it be that we are collectively incapable of empathy when a person crosses a certain threshold, be it power or art related, or motivated by racial or sexual politics? Could it be that we, the public, are constantly drawing lines in the sand — human vs. art, us vs. them — and using this as an excuse to manipulate or harm a body? There are, naturally, certain forms of art which invite human interaction more readily than others (I’m thinking of historically interactive forms like architecture and music, and the rising immersive theatre scene, for example) but the removal of real or artificial barriers—the proscenium stage in PLASTIC, or rules of civility in Rhythm 0 — often prove irresistible, and our darker tendencies emerge. It could be that public art involving human beings cannot be consumed by human beings in public without consequences.

[…] Having morphed from human into art as she climbed down, she was alchemized by the last stair and stood up, human once more.

Maria Hassabi and Marina Abramović have given us rich material to sift through and examine in our continued exploration of the human psyche. PLASTIC moved dancers through our public, transitional spaces, interrupted our movements and made us consider the crossing of a threshold, from human to art form. Abramović, throughout her career, invited the public into her art in the most personal way possible, giving spectators opportunities to find their own limits of cruelty and destruction, often sacrificing her body in the process. It is interesting and disturbing that we so quickly define ourselves in opposition to the art we see. Perhaps we can challenge ourselves to become aware of that cognitive dissonance we experience when we find ourselves up close and personal with a conflation of person and art in performance, and learn to transmute that double-take into tolerance, or better yet, understanding.