KATIE ROSENGARTEN

I think it’s fair to say that Hannah Gadsby does not want to be famous. I think it’d be just as fair to say she still doesn’t, even though her decisive, indicting “swan song,” Nanette, didn’t succeed in its goal of serving as Gadsby’s exit from comedy: earlier this year, almost a year after Gadsby’s show swept the tour circuit and grabbed the attention of global headlines, Gadsby announced an ensuing show, this time titled after one of her two beloved dogs, Douglas. Gadsby’s new show will take her on a tour of the United States, differing from Nanette’s stops primarily in Australia and the U.K.; fitting for the show’s content, which highlighted Gadsby’s experience growing up in a politically and socially homophobic Tasmania in the 1970’s, an experience to which she traces her introduction to tension — inner discomfort, emotional strain and anxiety — the key ingredient in the recipe for comedy as Gadsby lays it out for us: “Punch lines need trauma because punch lines […] need tension, and tension feeds trauma.” Gadsby’s name may not be in the titles of her shows, but her story is their starting place.

Hannah Gadsby: Nanette | Official Trailer [HD] | Netflix | Source: © Netflix/YouTube

Much of the coverage of Nanette, in trying to make sense of its simultaneous allure and hard-to-swallow deliverance of raw truth and trauma, identifies a “turning point” in the show: a switch from palatable dishing of joke after joke to jokes sandwiched between and punctually peppered with hard truths, whose impact makes you question what the correct reaction is — if there even is one. This analysis of her show’s structure fits the perception that what Gadsby achieves within this hour-long show is a subversion of comedy. This sentiment is not wrong, when the type of “comedy” we are expecting is that of the Ellen’s and Jimmy Fallon’s of today’s comedic limelight: a comedy that is just-political-enough to feel socially responsible but also digestible-enough that you come away with a belly full of warming laughter. And if you came into Gadsby’s show with that expectation and understanding of comedy, of course Gadsby’s performance seems like a precise, premeditated subverting of such a beloved genre. However, if you pay attention during the first half of the show and unravel the implications and contexts of many of Gadsby’s seemingly harmless opening jokes, they are no more palatable than the later ones. The real change in tone in Nanette is: at first Gadsby wants you to laugh, and later she wants you to listen.

Fame is a populist game; we choose the people we mark as famous, and in turn whose and which narratives we put onstage.

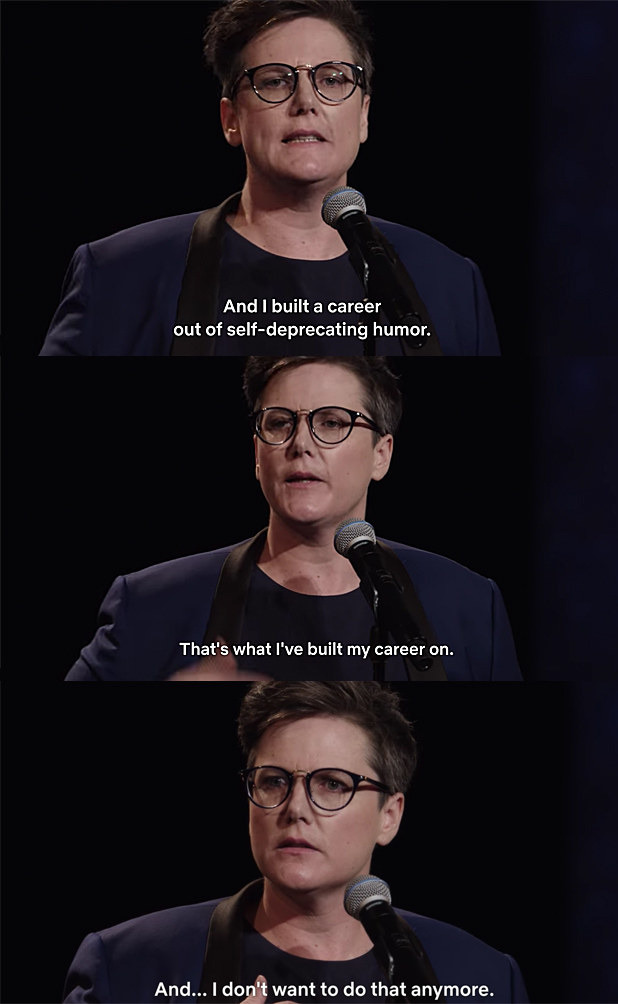

Hannah Gadsby in Nanette | Source: textonly/Tumblr

Gadsby’s show isn’t easy, and it certainly isn’t for those looking for an easy laugh. If you laugh easily at Gadsby’s jokes, you may want to reorient and reconsider what you find funny and why you find it funny in the first place. Gadsby is hilarious — undeniably so. However, she tells us exactly why she is funny while maintaining her uniquely hilarious and exacting sense of humor. And what makes Gadsby unique in her sense of humor and performance is just that: it is decidedly, unavoidably, genetically hers. While most jokes, even simple knock-knocks, are ruined when someone explains (*mansplains?*) them, Gadsby’s explanation is almost like a flight attendant reading the safety guidelines before the airplane takes flight; she is preparing you to follow along, pick up on, and prepare for the various ways she is going to rocket the performance to a high altitude, all while maintaining your individual comfort and safety. Gadsby’s calculus of humor — tension + punchline = diffusion — acknowledges that the tension must be sourced from somewhere, and, as she says herself, when she steps on a stage — with her stockier frame, cropped haircut, and questionably masculine (or, really, not-conventionally-feminine) presentation — her appearance usually provides all the tension an audience needs — that is, provided that she, the source of the tension, offer punchlines for them to help diffuse the thick of it.

The power of Gadsby’s special is that she declares, at the first deep dive into the real content of her special (there are many, and each is worth highlighting), that she will no longer partake in this dynamic. In a corrosive, unabashed call out to her audience, and perhaps the broader, imagined audience of all comedy in general, Gadsby declares: “This is an abusive relationship.” And in an even more painful moment milliseconds after she has said it, the audience laughs. In fairness to them, this is exactly what they have been primed to do.

If you laugh easily at Gadsby’s jokes, you may want to reorient and reconsider what you find funny and why you find it funny in the first place.

Hannah Gadsby in Nanette | Source: Movies & Chill/Tumblr

Gadsby’s show would not have been successful without the very discourse of comedy she seeks to contest. Without the ability to smoothly navigate the choppy surf of back-to-back quips and sighs of reliefs, quick jabs and easy amends, Gadsby would not be able to achieve the tour de force performance that she delivers: comedy — enjoyable, memorable, laugh-worthy comedy — served with a giant dollop of demanded societal introspection, beginning with a system of storytelling and sharing that prioritizes shared humanity over hate-fueled fear. In what seems like an off-hand comment, slyly sandwiched between jokes about her native Tasmania’s two claims to fame (the potato and its “frighteningly small gene pool”), almost as if to put it out there and see if you notice what she’s getting at, Gadsby utters: “I wish I was joking.” Gadsby may be funny, but she’s certainly not joking. And so, even as she lambasts comedy’s lack of efficacy, it is difficult to fully separate the performance from the genre.

What is comedy about, then, if not fame, notoriety? Possibly, using the currency and performance of identity to generate precious social capital: namely, attention? Nanette might not be about fame on the surface; the name of the special derives from a woman of the same name whom Gadsby met, and (as she tells it) cheekily thought, “I bet I could squeeze an hour of laughs out of you” — a prediction which, sadly, failed — an early indicator that the special of the same name would not be a laugh factory. Fame is held up by power structures, and reputation is the currency of partaking in the fame game. Gadsby devotes a large chunk of her special to analyzing two “great men” of art history, a field in which Gadsby holds a degree, as well as many complicated and scissor-sharp opinions. After reminding us that Van Gogh was not celebrated in his own lifetime because he was mentally unstable (not, as Art History 101 textbooks like to nicely package, because he was “born ahead of his time” — an idiom which Gadsby hilariously states is, factually, “impossible!”), and that Picasso was similarly “ailed” by a “mental illness” of misogyny, she states: “We think reputation is more important than anything else, including humanity.”

The punch of the punch line comes at the cost of the person telling it, most painfully when that line is told at the cost of that person’s inner, innate tension, built up from years of taught self-hatred while existing in the margins of a society that does not welcome their otherness.

It is this prioritization of great men and chosen narratives that elides over the stories of the people who suffer, sometimes at the hands of the very people our chosen narratives herald. Gadsby’s is one of those very narratives, and, despite her insistence that she must quit comedy, Nanette is (I hope) just the start of what she has to say. We let these great men hold up the pillars of high art and high society, and yet we so often forget that with each epithet of “great” and “genius” and “creator” next to their gilded names, we continually reify and strengthen their hold on their role in our collective narrative without (re)interrogating their merit in holding such precious and precarious spots. Without such an inquiry, by remaining complacent in our understanding of the world we have created, we cannot think of even the possibility of digging up conflicting or different narratives, whether in the past or the present. And furthermore, perhaps even more powerfully, if we cannot do that for the past or the present, there is little hope for doing any better success in the future endeavor of broadening our narrative scope — and, with it, our sense of connection and community.

Renaissance Woman: Venus on a Clam | Source: © Hannah Gadsby/YouTube

In our understood social contract, we uphold comedy and laughter as a kind of societal “medicine” (although Gadsby reminds us that penicillin might do the job as well). Earlier on in the special, Gadsby peppers in another seemingly unimportant line, saying, after a few quick jabs at the heavy subjects of toxic masculinity and the benefits of being a straight white male in today’s society — an identity she herself often gets mistaken for — “It’s just jokes though, just jokes. Banter.” But banter at whose cost? And for what effect? And with what subtext? Let us not forget that while Gadsby herself may get mistaken for a man in her out-of-focus, misguided small Tasmanian towns, it is far riskier for her, herself, to tell such jokes on a stage than an actual white man. Banter — with loved ones, with friends, with a comedian on a stage and you in an audience seat — only perpetuates the cycle of narratives that only let stories end in punchlines and tension-diffusers. The punch of the punch line comes at the cost of the person telling it, most painfully when that line is told at the cost of that person’s inner, innate tension, built up from years of taught self-hatred while existing in the margins of a society that does not welcome their otherness.

Nanette star Hannah Gadsby’s speech about ‘Jimmys’ and misogyny | Source: © Guardian Culture/YouTube

All of this may cause you to ask: why then would Gadsby put her swan song on Netflix, for millions to stream and watch? Gadsby is certainly aware throughout the special that her audience is a part of this entire experience: she notes at different points that, on the one hand, her lesbian audience loves to give “feedback,” while her male audience loves to provide “opinions.” After a string of jokes about the imagined ways in which her humor in Nanette might, ironically, disappoint her lesbian audience, she says: “Imagine the feedback.” And I can only imagine that she has, in fact, continually throughout her career. The notion of becoming famous by being funny is the very paradigm that Gadsby attempts to classify as a destructive pattern: if the people who are so often the ones labeled as “funny” or “class clowns” are usually the ones who are different, who keep humor as a tool in their tool belt for self-preservation against a society that prefers to be defensively normal and fearful of any identities that don’t fit squarely into their normative shapes, then their humor “[isn’t] humility. It’s humiliation.”

Hannah Gadsby in Nanette | Source: Buzzfeed/Tumblr

Perhaps the most radical part of Nanette, then, is Gadsby’s refusal to humiliate herself, while forcing her audience to reckon with a legacy of complicity that we all bear. Gadsby’s story is at the heart of Nanette — and this time she is not letting it end in a perfectly calculated punchline, held mid-tension, and diffused at her own cost, by her own jokes. In telling it “properly,” Gadsby places her story into our hands. Gadsby exploits, highlights, and explicitly calls upon the responsibility of the audience — which it has always had, whether during a comedic or dramatic performance — by reminding us the following:

“I just needed my story heard, my story felt and understood by individuals with minds of their own. Because, like it or not, your story… is my story. And my story… is your story. I just don’t have the strength to take care of my story anymore. I don’t want my story defined by anger. All I can ask is just please help me take care of my story.”

I hope that we can do so, by continuing to uphold Gadsby’s reputation not only as a high-class highwire comedian, but as a storyteller. Fame is a populist game; we choose the people we mark as famous, and in turn whose and which narratives we put onstage. Gadsby doesn’t provide us with an answer with how to proceed, simply an example of what it would take for us to encounter someone brave enough — rather, tired enough — to tell their story properly, in full. In a powerful refrain that holds together the final notes of her performance, Gadsby repeats: “Fuck reputation. Hindsight is a gift. [Can you] stop wasting my time!?”

Hannah Gadsby in Nanette | Source: textonly/Tumblr

What would it mean, as a society, to stop wasting our — and Gadsby’s — time, using the gift of hindsight, and throwing reputation to the wind? What would it take for us consumers, complicit in the sorting hat of who gets to be famous and who doesn’t, to make space for more and more unconventional narratives — no matter how painful, no matter how different, no matter how uncomfortable? Given Gadsby’s method, I’d imagine there might be a laugh involved, and certainly some tears.